99490 AWE 16 07 Article Jup

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Impact of Greek Classics Model on Indian Era

Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol. 13, Issue No. 2, July-2017, ISSN 2230-7540 Impact of Greek Classics Model on Indian Era Ms. Sangeeta* Assistant Professor, Arya Kanya Gurukul, Village More -Majra, Distt. Karnal, Haryana, India Abstract – The ancient Greeks were the “inventors” of more elements of civilization than any other people of the world. These elements of civilization can be viewed among historical writings especially associated with Herodotus and Thucydides, and the evolution of Democracy having foundational seeds in Athens. The Greeks view of the world was predominantly secular and rationalistic. It exalted the spirit of free inquiry and preferred knowledge to faith. With only a limited cultural inheritance of the past upon which to build, the Greeks produced intellectual and artistic monuments that had served ever since as standards of achievement. So in some ways the single most legacy of the ancient Greece is the civilization in India and ancient era is particularly influenced by the Greeks, especially in Art, language, culture and mostly covers the all aspects of Human life. This article is an attempt to explore cultural and religious evolution of India as an outcome of Indo Greek interaction. It further attempts to answer that why and how the India was influenced by the Greeks, Subsequently the Indian art particularly Gandhara appeared as the world’s famous Art of India. Keywords: Greek, Classics Model, Indian Era, Culture, People, World, Civilization, Evolution, Achievement, Human Life, etc. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - INTRODUCTION REVIEW OF LITERATURE: The advent of Greeks in India dates back from 6th The role of Greeks in India is largely associated with century (BC) to 5th century (AD) as an outcome of invasion of Alexander on India; whereas, the historical Greek expedition towards Persia. -

Teachers' Pay in Ancient Greece

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska 5-1942 Teachers' Pay In Ancient Greece Clarence A. Forbes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Teachers' Pay In Ancient Greece * * * * * CLARENCE A. FORBES UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA STUDIES Ma y 1942 STUDIES IN THE HUMANITIES NO.2 Note to Cataloger UNDER a new plan the volume number as well as the copy number of the University of Nebraska Studies was discontinued and only the numbering of the subseries carried on, distinguished by the month and the year of pu blica tion. Thus the present paper continues the subseries "Studies in the Humanities" begun with "University of Nebraska Studies, Volume 41, Number 2, August 1941." The other subseries of the University of Nebraska Studies, "Studies in Science and Technology," and "Studies in Social Science," are continued according to the above plan. Publications in all three subseries will be supplied to recipients of the "University Studies" series. Corre spondence and orders should be addressed to the Uni versity Editor, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. University of Nebraska Studies May 1942 TEACHERS' PAY IN ANCIENT GREECE * * * CLARENCE A. -

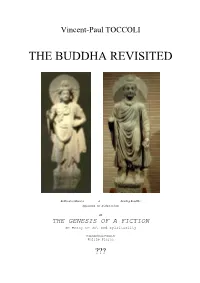

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Intersecting Identities: Cultural and Traditional Allegiance in Portrait of an Emir

INTERSECTING IDENTITIES: CULTURAL AND TRADITIONAL ALLEGIANCE IN PORTRAIT OF AN EMIR Ariana Panbechi In Iranian history, the period between the eighteenth and early twentieth centuries can be best described as an era of monumental change. Transformations in economics, technology, military administration, and the arts reverberated across the Persian Empire and were further developed by the Qajar dynasty, which was quick to embrace the technological and industrial innovations of modernism. 1 However, the Qajars were also strongly devoted to tradition, and utilized customary Persian motifs and themes to craft an imperial identity that solidified their position as the successors to the Persian imperial lineage.2 This desire to align with the past manifested in the visual arts, namely in large-scale royal portraiture of the Qajar monarchy and ruling elite. Executed in 1855, Portrait of an Emir (Fig. 1) is a depiction of an aristocrat that represents the Qajar devotion to reviving traditional imagery through art in an attempt to craft a nationalist identity. The work portrays a Qajar nobleman dressed in lavish robes and seated on a two-tone carpet within a palatial setting. The subject is identified as Emir Qasem Khan in the inscription that appears to the left of his head.3 Figure 1. Attributed to Afrasiyab, Portrait of an Emir, 1855. Oil on cotton, 59 x 37 in. Brooklyn Museum, accession number 73.145. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles K. Wilkinson, Brooklyn, New York. Image courtesy the Brooklyn Museum. In this paper, I argue that Emir Qasem Khan’s portrait, as a pictorial representation of how he presented himself during his lifetime, is a visualization of the different entities, ideas, and traditions that informed his carefully crafted identity as a member of the Qajar court. -

ART XVI.—On the Identity of Xandrames and Krananda

447 ART XVI.—On the Identity of Xandrames and Krananda. By EDWARD THOMAS, ESQ. AT the meeting of the Royal Asiatic Society, on the 21st Nov., 1864,1 undertook the task of establishing the identity of the Xandrames of Diodorus Siculus and Quintus Curtius, the undesignated king of the Gangetic provinces of other Classic Authors—with the potentate whose name appears on a very extensive series of local mintages under the bilingual Bactrian and Indo-Pali form of Krananda. With the very open array of optional readings of the name afforded by the Greek, Latin, Arabic, or Persian tran- scriptions, I need scarcely enter upon any vindication for con- centrating the whole cifcle of misnomers in the doubly autho- ritative version the coins have perpetuated: my endeavours will be confined to sustaining the reasonable probability of the contemporaneous existence of Alexander the Great and the Indian Krananda; to exemplifying the singularly appro- priate geographical currency and abundance of the coins themselves; and lastly to recapitulating the curious evidences bearing upon Krananda's individuality, supplied by indi- genous annals, and their strange coincidence with the legends preserved by the conterminous Persian epic and prose writers, occasionally reproduced by Arab translators, who, however, eventually sought more accurate knowledge from purely Indian sources. In the course of this inquiry, I shall be in a position to show, that Krananda was the prominent representative of the regnant fraternity of the " nine Nandas," and his coins, in their symbolic devices, will demonstrate for us, what no written history, home or foreign, has as yet explicitly de- clared, that the Nandas were Buddhists. -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

Iasbaba's 60 Days Plan – Day 35 (History)

IASbaba’s 60 Days Plan – Day 35 (History) 2018 Q.1) Consider the following pairs. Sculpture Material made from 1. Mother goddess Stone 2. Bearded priest Terracotta 3. Dancing girl Copper Which of the above pairs is/are correctly matched? a) 1 and 3 only b) 3 only c) All the above d) None Q.1) Solution (d) Terracotta: Terracotta figures are more realistic in Gujarat sites and Kalibangan. Toy carts with wheels, whistles, rattles, bird and animals, gamesmen, and discs were also rendered in terracotta. The most important terracotta figures are those represent Mother Goddess. Stone Statues: Stone statues found in Indus valley sites are excellent examples of handling the 3D volume. Two major stone statues are: Bearded Man (Priest Man, Priest-King) and Male Torso Bronze Casting: Bronze casting was practiced in wide scale in almost all major sites of the civilization. The technique used for Bronze Casting was Lost Wax Technique. Dancing girl and bull from Mohenjo-Daro. Do you know? Thousands of seals were discovered from the sites, usually made of steatite, and occasionally of agate, chert, copper, faience and terracotta, with beautiful figures of animals such as unicorn bull, rhinoceros, tiger, elephant, bison, goat, buffalo, etc. Some seals were also been found in Gold and Ivory. THINK! 1 IASbaba’s 60 Days Plan – Day 35 (History) 2018 Harappan pottery. Q.2) Arrange the following parts of stupa from top to bottom. 1. Yasti 2. Harmika 3. Chatras 4. Anda Select the correct answer using the codes given below. a) 3-1-2-4 b) 3-2-1-4 c) 2-3-1-4 d) 2-1-3-4 Q.2) Solution (a) Stupa dome is called as Anda. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

Cape Comorin Volume II Issue II July 2020

ISSN: 2582-1962 Cape Comorin Volume II Issue II July 2020 An International Multidisciplinary Double-Blind Peer-reviewed Research Journal Maurya Dynasty. Myth, Legend or History Daya Dissanayake, Novelist, Poet and Blogger, Udumulla Road, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka Abstract: Over the past two centuries we have created a Maurya dynasty, or which should have been called a Chandragupta dynasty. Though Rama was deified, and the deification extended to Hanuman and Valmiki as we find at Ram Tirth in Amritsar, even Asoka Maurya has not been deified yet, leaving us the freedom to discuss the historicity of the Mauryas. In India Buddha and Mahavira have become founders of two great religious traditions. They are accepted as historical characters, and their biographies cannot be questioned, because it would amount to questioning the faith of people. About other people we come across in the long history of India, specially those who are believed to have lived Before the Common Era, we do not have any solid evidence of writing or archaeological remains to determine their historicity, chronology or about their lives. Their biographies are accepted by many as history, by a few as legends, and could even be considered myths only. We call him Chandragupta assuming he is the same Sandracottus of the Greeks. Bindusara is claimed to be his son, identified as Amitrocades. Aśoka/Devanampiya/Piyadassi is accepted as his grandson, but never mentioned by the Greeks, by any name, Greek or Indian. Chandragupta‟s biography was created by the British, selectively picking from secondary and tertiary Greek sources, and from a drama produced about eight centuries after Chandragupta. -

The Mauryan Empire Opens a New Era in the History Of

Winmeen Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Self Preparation Course 2018 History Part - 7 7] Maurya Empire MAURYAN EMPIRE NOTES Mauryan Empire (321 – 184 BC) The foundation of the Mauryan Empire opens a new era in the history of India and for the first time, the political unity was achieved in India. The history writing has also become clear from this period due to accuracy in chronology and sources. Besides plenty of indigenous and foreign literary sources, a number of epigraphical records are also available to write the history of this period. RISE OF MAURYAS The last of the Nanda rulers, Dhana Nanda was highly unpopular due to his oppressive tax regime. Also, post Alexander’s invasion of North-Western India, that region faced a lot of unrest from foreign powers. They were ruled by Indo-Greek rulers. Chandragupta, with the help of an intelligent and politically astute Brahmin, Kautilya usurped the throne by defeating Dhana Nanda in 321 BC. 1 www.winmeen.com | Learning Leads to Ruling Winmeen Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Self Preparation Course 2018 Chandragupta Maurya (322 – 298 B.C.) Chandragupta Maurya was the first ruler who unified entire country into one political unit, called the Mauryan Empire. He had captured Pataliputra from Dhanananda, who was the last ruler of the Nanda dynasty. He didn’t do achieve this feat alone, he was assisted by Kautilya, who was also known as Vishnugupta or Chanakya. Some scholars think that Chanakya was the real architect of this empire. After establishing his reign in the Gangetic valley, Chandragupta Maurya marched to the northwest and conquered territories upto the Indus.