Reverend Darwin's Detour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Streaked Bombardier Beetle (Brachinus Sclopeta) Is One of the UK’S Most Threatened Invertebrates with Modern Records Restricted to London’S Brownfields

© Benoit Martha The Streaked bombardier beetle (Brachinus sclopeta) is one of the UK’s most threatened invertebrates with modern records restricted to London’s brownfields. This easily identifiable beetle is 5-7.5mm long and has a metallic blue-green elytra with a distinctive orange-red streak, and a slim orange-red body. Similar to all bombardier species, when threatened it can spray a boiling, chemical mixture of hydroquinones and hydrogen peroxide from the tip of its flexible abdomen to deter predators. Life cycle Habitat Very little is known of their ecology, but adults have been Streaked bombardier in the UK are now exclusively recorded throughout the year in an apparently active state. It associated with brownfields that support open mosaic is likely that the Streaked bombardier follows a similar life habitat on previously developed land, a Priority Habitat. They cycle to closely related species, with reproduction in the require sites with a mosaic of dry open ground, ruderal warmer months before overwintering as adults. It is thought vegetation and large debris such as broken bricks and rubble. that larvae are ectoparasites of Amara, Harpalus and Soil and rubble bunds created by site clearances appear to possibly Ophonus beetle larvae, attaching themselves to their provide them with optimal habitat, perhaps providing them prey and feeding before pupating. with a range of microclimates, aspects, temperature and moisture. The beetles are often found tightly embedded Distribution between broken brick or rubble and soil. A range of microclimates and different ruderal species are also likely to Historical records of the Streaked bombardier are restricted improve the number and diversity of seed eating Amara and to a handful of sites on the south coast of England, with the Harpalus prey species. -

How Bombardier Beetles Survive Being Eaten – and Other Amazing Animal Defence Mechanisms

07/02/2018 How bombardier beetles survive being eaten – and other amazing animal defence mechanisms Academic rigour, journalistic flair How bombardier beetles survive being eaten – and other amazing animal defence mechanisms February 7, 2018 12.03am GMT Author Luc Bussiere Lecturer in Biological Sciences, University of Stirling What goes in must come out. Sugiura & Sato, Kobe University, Author provided (No reuse) In Disney’s film version of Pinnochio, the boy-puppet rescues his creator Geppetto by lighting a fire inside Monstro the whale, who has swallowed them both. The fire causes the whale to sneeze, freeing Pinnochio and Geppetto from their gastric prison. Before you dismiss this getaway as incredible fantasy, consider that new research shows that a kind of fire in the belly can actually be an effective strategy for escaping predators in the real world. In fact, the animal kingdom is full of amazing examples of unusual defence mechanisms that help small creatures avoid a nasty fate. In a new paper in Biology Letters, scientists at Kobe University in Japan describe how bombardier beetles can survive being eaten by a toad by releasing a hot chemical spray that makes the hungry amphibian vomit. Bombardier beetles are so-named because, when threatened, they emit a boiling, irritating substance from their backsides with remarkable accuracy, to deter potential predators. They produce the caustic mixture by combining hydrogen peroxide, hydroquinones and chemical catalysts in a specially reinforced chamber at the base of their abdomen, which shields the beetle’s own organs from the resulting explosive reaction. Slow-motion footage of spraying by Asian bombardier beetle https://theconversation.com/how-bombardier-beetles-survive-being-eaten-and-other-amazing-animal-defence-mechanisms-91288 1/4 07/02/2018 How bombardier beetles survive being eaten – and other amazing animal defence mechanisms The Japanese researchers fed two different species of bombardier beetles to captive toads. -

Mechanistic Origins of Bombardier Beetle (Brachinini)

RESEARCH | REPORTS performed, it can never be fully excluded that the 8. K. M. Tye et al., Nature 471, 358–362 (2011). 30. S. Ruediger, D. Spirig, F. Donato, P. Caroni, Nat. Neurosci. 15, anxiety- and goal-related firing described here 9. A. Adhikari, M. A. Topiwala, J. A. Gordon, Neuron 65, 257–269 1563–1571 (2012). may reflect more complex aspects and compu- (2010). 10. E. Likhtik, J. M. Stujenske, M. A. Topiwala, A. Z. Harris, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS tations of the vCA1 network. J. A. Gordon, Nat. Neurosci. 17, 106–113 (2014). We thank P. Schönenberger [Institute of Science and Technology The mPFC and Amy are involved in anxiety 11. R. P. Vertes, Synapse 51,32–58 (2004). (IST), Klosterneuburg, Austria] and S. Wolff (Harvard Medical behavior, receiving direct inputs from vCA1 (2, 4, 8). 12. C. A. Orsini, J. H. Kim, E. Knapska, S. Maren, J. Neurosci. 31, School, Boston, USA) for helpful discussions on the optogenetic – We demonstrated that anxiety-related activity is 17269 17277 (2011). strategy; T. Asenov (IST) for three-dimensional printing of → 13. S. Royer, A. Sirota, J. Patel, G. Buzsáki, J. Neurosci. 30, microdrives; R. Tomioka (Kumamoto University, Japan) for help preferentially supported by vCA1 mPFC pro- 1777–1787 (2010). in setting up the behavioral and electrophysiological experiments; jections, in agreement with described theta- 14. D. M. Bannerman et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 181–192 E. Borok and R. Hauer for technical help with histology; all the frequency synchronization between the ventral (2014). members of the Klausberger lab for insightful discussions; hippocampus and mPFC during anxiety behavior 15. -

The Evolution and Phylogeny of Beetles

Darwin, Beetles and Phylogenetics Rolf G. Beutel1 . Frank Friedrich1, 2 . Richard A. B. Leschen3 1) Entomology group, Institut für Spezielle Zoologie und Evolutionsbiologie mit Phyletischem Museum, FSU Jena, 07743 Jena; e-mail: [email protected]; 2) Biozentrum Grindel und Zoologisches Museum, Universität Hamburg, 20144 Hamburg; 3) New Zealand Arthropod Collection, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, NZ Whenever I hear of the capture of rare beetles, I feel like an old warhorse at the sound of a trumpet. Charles R. Darwin Abstract Here we review Charles Darwin’s relation to beetles and developments in coleopteran systematics in the last two centuries. Darwin was an enthusiastic beetle collector. He used beetles to illustrate different evolutionary phenomena in his major works, and astonishingly, an entire sub-chapter is dedicated to beetles in “The Descent of Man”. During his voyage on the Beagle, Darwin was impressed by the high diversity of beetles in the tropics and expressed, to his surprise, that the majority of species were small and inconspicuous. Despite his obvious interest in the group he did not get involved in beetle taxonomy and his theoretical work had little immediate impact on beetle classification. The development of taxonomy and classification in the late 19th and earlier 20th centuries was mainly characterised by the exploration of new character systems (e.g., larval features, wing venation). In the mid 20th century Hennig’s new methodology to group lineages by derived characters revolutionised systematics of Coleoptera and other organisms. As envisioned by Darwin and Ernst Haeckel, the new Hennigian approach enabled systematists to establish classifications truly reflecting evolution. -

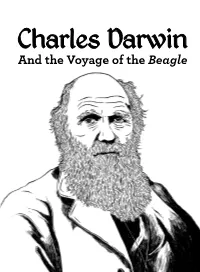

Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle

Charles Darwin And the Voyage of the Beagle Darwin interior proof.indd 1 10/8/19 12:19 PM To Ernie —R. A. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHING COMPANY INC. 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2009 by Ruth Ashby Charles Darwin First trade paperback edition published in 2020 And the Voyage of the Beagle All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the pub- lisher. Book design and composition by Adela Pons Printed in October 2019 in the United States of America by RR Donnelley & Sons in Harrisonburg, Ruth Ashby Virginia 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 (hardcover) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 (trade paperback) HC ISBN: 978-1-56145-478-5 PB ISBN: 978-1-68263-127-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashby, Ruth. Young Charles Darwin and the voyage of the Beagle / written by Ruth Ashby.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-478-5 / ISBN 10: 1-56145-478-8 1. Darwin, Charles, 1809-1882.—Juvenile literature. 2. Beagle Expedition (1831-1836)— Juvenile literature. 3. Naturalist—England—Biography—Juvenile literature. 4. Voyages around the world—Juvenile literature. I. Title. QH31.D2.A797 2009 910.4’1—dc22 2008036747 Darwin interior proof.indd 2-3 10/8/19 12:19 PM The Voyage of the Beagle Approximate Route, 1831–1836 B R I T I S H ISLANDS N WE EUROPE N O R T H S AMERICA ASIA NORTH CANARY ISLANDS ATLANTIC OCEAN PACIFIC CAPE VERDE ISLANDS OCEAN AFRICA INDIAN OCEAN GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS SOUTH To MADAGASCAR Tahiti AMERICA Bahia Lima Rio de Janeiro ST. -

Bizarre Insect Defences Bizarre Insect £7.99 by Ruth Owen and Ross Piper Xxxxxxxxx Published in 2018 by Ruby Tuesday Books Ltd

The Secret Lives of Insects Lives The Secret Disguises, Explosions & Boiling Farts Disguises, Bizarre Insect Defences Titles in this series Ruth Owen and Ross Piper Ruth Owen ISBN: 978-1-78856-003-0 £7.99 9 781788 560030 by Ruth Owen and Ross Piper XxXxXxXxX Published in 2018 by Ruby Tuesday Books Ltd. Contents Copyright © 2018 Ruby Tuesday Books Ltd. Masters of Defence............................................... 4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, stored Take Aim, Fire! in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Wood.Ant............................................................6 A Very Sticky End Editor: Mark J. Sachner Designer: Emma Randall Exploding.Carpenter.Ant.................................. 8 Production: John Lingham Butts of Fire Photo credits Bombardier.Beetle........................................... 10 Alamy: 24, 27 (bottom centre), 28 (bottom), 29 (bottom left); Creative Commons: 15 (bottom), 25 (top); FLPA: 4, 9 (bottom), 14, 16, 20, 27 (bottom left); Getty Images: 19 (top), 25 (bottom); A Butt-propelled Getaway Istock Photo: 6 (bottom); Nature Picture Library: 5 (centre), 6–7, 10, 15 (top); Ross Piper: 12 Stenus.Rove.Beetle........................................... 12 (centre), 13 (bottom); Ruby Tuesday Books: 12 (bottom); Shutterstock: Cover, 1, 5 (top), 5 (bottom), 7 (centre), 8, 11, 13 (top), 17, 18, 19 (bottom), 21, 22–23, 26, 27 (top), 27 (bottom A Night-time Battle right), 28 (top), 29 (top), 29 (centre), 29 (bottom right), 31. Tiger.Moth........................................................ 14 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data (CIP) is available for this title. Warning Signs and Deadly Bubbles Koppie.Foam.Grasshopper............................ -

Evolution and Control of Complexity: Key Experiments Using Sources of Hard X-Rays” Was Convened at Argonne National Laboratory in October 2010

Workshop Advisory Committee Gabe Aeppli (LCN London) Massimo Altarelli (Euro-XFEL ) Andrea Cavalleri (Oxford/DESY) Lin Chen (Argonne/Northwestern) George Crabtree (Argonne) Helmut Dosch (DESY) Janos Hajdu (Uppsala) Sol Gruner (Cornell) Jerry Hastings (SLAC) Rus Hemley (Carnegie Institute) Eric Isaacs (Argonne) Ben Larson (Oak Ridge) Richard Lee (Livermore) Ingolf Lindau (SLAC) Denny Mills (Argonne) Keith Moffat (Univ. Chicago) David Moncton (MIT) Harald Reichert (ESRF) Jo Stöhr (SLAC) Lou Terminello (PNNL) Linda Young (Argonne) Soichi Wakatsuki (KEK) Workshop Coordinator Anne Owens Workshop Chairs Uwe Bergmann, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory Gopal Shenoy, Argonne National Laboratory Edgar Weckert, Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron, DES Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... vii 1 Background to the Workshop: Understanding the Evolution of Complexity ............................. 1 2 The Characteristics of Hard X-rays to Probe the Evolution of Complexity ................................. 9 2.1 Compact Light Sources .......................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Storage Rings ........................................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Energy-Recovery Linacs ........................................................................................................ 11 2.4 X-ray FELs ............................................................................................................................. -

A Review of Myrmecophily in Ant Nest Beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Paussinae): Linking Early Observations with Recent Findings

Naturwissenschaften (2007) 94:871–894 DOI 10.1007/s00114-007-0271-x REVIEW A review of myrmecophily in ant nest beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Paussinae): linking early observations with recent findings Stefanie F. Geiselhardt & Klaus Peschke & Peter Nagel Received: 15 November 2005 /Revised: 28 February 2007 /Accepted: 9 May 2007 / Published online: 12 June 2007 # Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Myrmecophily provides various examples of as “bombardier beetles” is not used in contact with host how social structures can be overcome to exploit vast and ants. We attempt to trace the evolution of myrmecophily in well-protected resources. Ant nest beetles (Paussinae) are paussines by reviewing important aspects of the association particularly well suited for ecological and evolutionary between paussine beetles and ants, i.e. morphological and considerations in the context of association with ants potential chemical adaptations, life cycle, host specificity, because life habits within the subfamily range from free- alimentation, parasitism and sound production. living and predatory in basal taxa to obligatory myrme- cophily in derived Paussini. Adult Paussini are accepted in Keywords Evolution of myrmecophily. Paussinae . the ant society, although parasitising the colony by preying Mimicry. Ant parasites . Defensive secretion . on ant brood. Host species mainly belong to the ant families Host specificity Myrmicinae and Formicinae, but at least several paussine genera are not host-specific. Morphological adaptations, such as special glands and associated tufts of hair Introduction (trichomes), characterise Paussini as typical myrmecophiles and lead to two different strategical types of body shape: A great diversity of arthropods live together with ants and while certain Paussini rely on the protective type with less profit from ant societies being well-protected habitats with exposed extremities, other genera access ant colonies using stable microclimate (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990; Wasmann glandular secretions and trichomes (symphile type). -

20Th Anniversary 1994-2014 EPSRC 20Th Anniversary CONTENTS 1994-2014

EPSRC 20th Anniversary 1994-2014 EPSRC 20th anniversary CONTENTS 1994-2014 4-9 1994: EPSRC comes into being; 60-69 2005: Green chemistry steps up Peter Denyer starts a camera phone a gear; new facial recognition software revolution; Stephen Salter trailblazes becomes a Crimewatch favourite; modern wave energy research researchers begin mapping the underworld 10-13 1995: From microwave ovens to 70-73 2006: The Silent Aircraft Initiative biomedical engineering, Professor Lionel heralds a greener era in air travel; bacteria Tarassenko’s remarkable career; Professor munch metal, get recycled, emit hydrogen Peter Bruce – batteries for tomorrow 14 74-81 2007: A pioneering approach to 14-19 1996: Professor Alf Adams, prepare against earthquakes and tsunamis; godfather of the internet; Professor Dame beetles inspire high technologies; spin out Wendy Hall – web science pioneer company sells for US$500 million 20-23 1997: The crucial science behind 82-87 2008: Four scientists tackle the world’s first supersonic car; Professor synthetic cells; the 1,000 mph supercar; Malcolm Greaves – oil magnate strategic healthcare partnerships; supercomputer facility is launched 24-27 1998: Professor Kevin Shakesheff – regeneration man; Professor Ed Hinds – 88-95 2009: Massive investments in 20 order from quantum chaos doctoral training; the 175 mph racing car you can eat; rescuing heritage buildings; 28-31 1999: Professor Sir Mike Brady – medical imaging innovator; Unlocking the the battery-free soldier Basic Technologies programme 96-101 2010: Unlocking the -

A Bombardier Beetle Pheropsophus Aequinoctialis (L.) (Insecta: Coleoptera: Carabidae)1 Gregory Parrow and Adam Dale2

EENY-765 A Bombardier Beetle Pheropsophus aequinoctialis (L.) (Insecta: Coleoptera: Carabidae)1 Gregory Parrow and Adam Dale2 Introduction aequinoctialis typically inhabits riverbanks, sandbars, or in soils adjacent to bodies of freshwater, areas where Pheropsophus aequinoctialis (L.) is a carabid beetle in the Neoscapteriscus mole cricket species also inhabit (Frank et tribe Brachinini that is native to parts of South and Central al. 2009). America (Frank et al. 2009). Ground beetles of this tribe are commonly referred to as bombardier beetles due to their ability to produce a powerful and hot defensive chemical spray directed at would-be predators (Ferreira and Terra 1989). This spray is capable of harming humans, resulting in discomfort, physical burns (due to the spray temperature), and possibly contact dermatitis. In rare cases, systemic reactions requiring more urgent medical attention have been reported (Pardal et al. 2016). The adults of this species (Figure 1) are nocturnal and believed to be generalist predators and scavengers. However, larval stages (Figures 2 and 3) appear to depend on an exclusive diet of Figure 1. Adult Pheropsophus aequinoctialis. mole cricket eggs (Frank et al. 2009). As such, Pheropsophus Credits: Lyle Buss, UF/IFAS aequinoctialis is considered to have potential use as a biological control agent against certain invasive mole Life Cycle cricket pests in North America (Frank et al. 2009). Eggs Pheropsophus aequinoctialis eggs are white in color and Distribution have an elongate profile with slightly rounded ends. When Literature suggests that this insect was historically found magnified, the egg’s surface appears highly perforated, primarily in north and northeastern Brazil (Ferreira and displaying numerous polygonal facets (Frank et al. -

Teaching Notes – the Genius of Bugs

TE PAPA PRESS TEACHING NOTES The Genius of Bugs Simon Pollard They may be small, they may be creepy, but bugs have super-sized powers! Meet a roll call of some of New Zealand and the world’s most incredible bugs – from the cunning portia spider to the killer brain-surgeon jewel wasp. The Genius of Bugs is a new, fresh take on bugs, packed with tales, facts and figures that showcase bug ingenuity and reveal astounding bug behaviour. Specifications IMPRINT: Te Papa Press CATEGORY: Children’s non-fiction PUBLICATION DATE: December 2016 ISBN: 978–0–9941362-1-3 RRP: $24.99 PAGE EXTENT: 32 pages, portrait FORMAT: Paperback SIZE: 270mm x 210mm ILLUSTRATIONS: Full-colour throughout READERSHIP: 6+ Simon Pollard is a successful children’s book author, spider expert and natural history writer. Currently Adjunct Professor TEACHING NOTES INCLUDE: of Science Communication at the University of Canterbury, • 7 Before-reading questions Simon is the author of the award-winning I Am a Spider (Reed, • 29 Close-reading questions 2004) and I Am an Insect (Reed, 2002). He is a frequent • 8 Language and style questions contributor to Natural History (US), BBC Wildlife (UK), New • 34 Activities and creative responses Zealand Geographic and Nature Australia magazines and across a range of curriculum areas has worked as an advisor and script writer for many natural (Literacy, Numeracy, Science, Social history documentaries, including The Hunt (BBC, 2015) and sciences, the Arts, Technology and Planet Earth (BBC, 2006). His book Dear Alison (Penguin, Physical education and health). 2009) won the 2010 Children’s Choice Award for non-fiction at the New Zealand Post Children’s Book Awards and the 2010 LIANZA Elsie Locke Award, Non-fiction Book of the Year. -

Unusual Toxic Accident Caused by Calosoma Alternans, Fabricius 1792

Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical. 2021;73(2):e609 Presentación de caso Unusual toxic accident caused by Calosoma alternans, Fabricius 1792 (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in a Venezuelan patient Accidente tóxico inusual provocado por Calosoma alternans, Fabricius 1792 (Coleoptera: Carabidae) en un paciente venezolano Gisselle C. Gil-Zambrano1 https://orcid.org/ 0000-0002-5191-4617 Rafael M. Reyes-Lugo2 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4099-5033 Iván Salvi2 https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3699-6674 Alexis Rodriguez-Acosta3* https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1234-7522 1Instituto de Inmunología “Dr. Nicolás Bianco” de la Universidad Central de Venezuela. Caracas, República Bolivariana de Venezuela. 2Instituto de Medicina Tropical de la Universidad Central de Venezuela, Sección de Entomología “Dr. Pablo Anduze”, Caracas, República Bolivariana de Venezuela. 3Instituto Anatómico “Dr. José Izquierdo” de la Universidad Central de Venezuela, Laboratorio de Inmunoquímica y Ultraestructura. Caracas, República Bolivariana de Venezuela. *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Coleopteran insects can produce toxic substances containing multiple components which have so far not been properly described. To report an unusual case of intoxication by excretion from Calosoma alternans Fabricius 1792 (Coleoptera: Carabidae) in a Venezuelan patient from a periurban neighborhood near the mesothermal raining forest. The toxic activity caused a clinical status characterized by digestive symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, epigastralgia, an increase in bowel movements and probable kidney inflammation with intense pain in both lumbar regions, which did not correspond to the classic dermal damage. In conclusion, a unique case is presented of intoxication by a coleopteran species, with a clinical description not previously reported. Keywords: Adephaga; intoxication; Carabidae; coleopteran; Calosoma alternans.