Perronneau, D'aubais

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daac Partie 2 -Strategie V13112018

Document Approuvé le 10 Décembre 2019 Document d'Aménagement Artisanal et Commercial DAAC STRATEGIE 1 Document d'Aménagement Artisanal et Commercial du SCoT Sud Gard PREAMBULE ......................................................................................................................................... 3 I. Qu'est- ce que le DAAC ? ......................................................................................................................... 4 II. L'organisation du DAAC ........................................................................................................................... 6 ARMATURE COMMERCIALE 2030 .......................................................................................................... 7 I. Les principes de localisation dans le PADD ............................................................................................. 8 II. L'armature commerciale projetée dans le DOO ...................................................................................... 9 III. Les différents niveaux d'offre ................................................................................................................ 12 ORIENTATIONS SPECIFIQUES PAR EPCI ................................................................................................ 19 IV. CA Nîmes Métropole ............................................................................................................................. 22 V. CC Beaucaire Terre d'Argence .............................................................................................................. -

Titre 1 Rapport Du Commissaire Enquêteur

DÉPARTEMENT DU GARD COMMUNE D’AIGUES VIVES ENQUÊTE PUBLIQUE Du 16 décembre 2019 au 17 janvier 2020 Référence : Arrêté N° 342/APEP/2019-1 du 18 novembre 2019 de Monsieur le Préfet du Gard Objet : Autorisation du renouvellement et de l’extension d’une carrière de matériaux alluvionnaires, d’une installation de traitement de matériaux et d’une installation de transit de produits minéraux solides et l’accueil de déchets non dangereux inertes, lieux dits « Bas Mas Rouge », « Le Clapas » et « Grange de Paul Gros », présentée par les Ets Lazard d’Aigues Vives 30 Titre 1 Rapport du commissaire enquêteur Jacques CIMETIÈRE Commissaire Enquêteur TABLE DES MATIÈRES 1 GÉNÉRALITÉS : ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PRESENTATION GENERALE (CF. RAPPORT DE PRESENTATION ET INTERNET) : ............................................................... 1 1.2 OBJET DE L’ENQUETE PUBLIQUE. ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 IDENTITE DU DEMANDEUR : ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 CADRE JURIDIQUE : ........................................................................................................................................ 2 CODE DE L'ENVIRONNEMENT ET NOTAMMENT LES ARTICLES L123-1 A L123-16, L511-1 A L517-2 ET R123-1 ET SUIVANTS RELATIFS AUX ENQUETES PUBLIQUES -

Croix N° 30 : La Croix Des Templiers

Croix n° 30 : La croix des templiers Cette croix est gravée dans la pierre près de la porte d’une maison au Castellas. Il s’agirait d’une croix des chevaliers des templiers. D’après certains auteurs ayant effectué des recherches sur le village, le « Monastère – Prieuré de ST CHRISTOPHE ; » à Castillon ( bas de la cloroute ) aurait pu être « occupé » par des chevaliers des templiers. Une maison des templiers aurait existé près de cette église. Par ailleurs, on raconte dans le village, que dans le puis « du Soulier », aux abords de cette église, se trouverait une « chèvre d’or », qui contiendrait l’or des templiers. Selon un document datant de 1183, les chevaliers de l’ordre des templiers possédaient le Monastère de St Etienne situé à St Hilaire d’ Ozilhan. Les templiers sont avant tout un ordre religieux et par conséquent ils arboraient fièrement la croix comme symbole. Toutefois ils modifièrent la croix chrétienne classique pour créer une croix pattée qui devint rapidement leur emblème. Notre région est donc une des plus anciennes provinces de l’Ordre du Temple avec des Commanderies très puissantes comme Montpellier qui entre 1216 et 1234 supplante Marseille en qualité de « Port Templier ». St Gilles, dernier lieu de rassemblement avant l’embarquement vers la Terre Sainte, et Nîmes avec une forte concentration de troupes et de biens. A Nîmes, en 1145 un vaste terrain leur avait été donné près de la porte de la Couronne, au dessous de l’Esplanade (emplacement du Lycée Feuchères) où ils construisaient leur église en 1151 sous le nom de « Notre Dame du Temple ». -

Mise En Page 1

Guide d’accueil 2019 Welcome booklet T OFFICE DE T OURISME INTER COMMUNAL X Welkom gids VACANCES en Pays de Sommières PAYS DE SOMMIÈRES PAYS DE SOMMIÈRES Avec plaisir nous vous présentons ce qui nous tient à cœur : les attraits du Pays de Sommières, les monuments à visiter absolument, les villages au caractère singulier, les manifestations à ne pas manquer, les bons plans pour une découverte ludique et passionnante ! Dans ce guide vous trouvez toutes les adresses de nos partenaires sportifs, culturels ou de loisirs. Nos équipes sont à votre écoute pour organiser votre séjour. Elles connaissent parfaitement la région et tout ce qui la compose pour vous conseiller et partager avec vous leurs coups de cœur. Car notre objectif c’est la réussite de votre séjour ! Alors, prenez le temps de vivre ! Le Pays de Sommières est heureux de vous accueillir. Vous repartirez reposé et ressourcé, ou peut-être ne repartirez- vous plus jamais ... Pierre Martinez Président de la Communauté de communes du Pays de Sommières Jean-Louis Rivière Président de l'Office de Tourisme du Pays de Sommières intercommunal TThe attractive features of Pays de Sommières XIn deze gids stellen wij u de trekpleisters van are described in this guide: monuments, villages, het land van Sommières voor: de monumenten, events and ways of discovering the area that are de dorpen, de evenementen, goede ideeën voor both amusing and fascinating! Our teams are een ludieke en meeslepende ontdekking! Onze ready to help you organise your stay. They have teams staan tot uw dienst om uw verblijf te orga - perfect knowledge of the region and are here niseren. -

SOMMIÈRES Notre Combat Les Prix Bas Du Lundi Au Samedi De 8H30 À

GUIDE D’ACCUEIL 2014 LE PAYS DE SOMMIÈRES DES VACANCES AUTHENTIQUES www.ot-sommieres.fr 2 PAYS DE 3 SOMMIÈRES GUIDE D’ACCUEIL 2014 Cher visiteur, Vous avez envie de prendre le temps, de savourer l’instant présent ? D'entendre le bel accent du Sud, de visiter des vignobles de qualité Dear visitor, whaT are et des villages hors du temps, de flâner you looking for? A quieT sur des marchés du terroir ensoleillés ? place, far from The over - De faire de vraies découvertes en crowded TourisT spoTs? Do dehors des sentiers battus, d'apprécier you like The old TradiTional villages, farmers’ markeTs, la douceur d'une soirée d'été village fesTivals? Are you ou d'écouter le chant des cigales ? inTeresTed in ancienT hisTo - ry, archiTecTure? If This is Alors posez vos valises, ce que vous so, dear visiTor, look no cherchez est ici, en Pays de Sommières. furTher. You can find whaT you Ce guide vous aidera à profiter de are looking for here in The “Pays de Sommières”. votre séjour chez nous. We will welcome you for Vous y trouverez l’histoire du Pays one day, one weekend de Sommières, les bonnes adresses or for a longer sTay. pour vos activités sportives, de loisirs ou culturelles et beaucoup d’autres Laat u ontroeren Houdt u van de sfeer op de informations utiles. streekmarkten, de sfeer van de avonden in het zuiden? Le Pays de Sommières est heureux Wilt u 2000 jaar teruggaan de vous offrir toutes ces émotions. in architectuur, avonturen en Vous repartirez reposé et ressourcé, menselijke levens? Wilt u ou peut-être ne repartirez-vous plus .. -

Aigues-Vives Aubais Boissières Codognan Gallargues-Le-Montueux Mus Nages & Solorgues Uchaud Vergèze Vestric & Candiac

JOURNAL DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES RHÔNY-VISTRE- VIDOURLE N° 8 - FÉVRIER 2021 AIGUES-VIVES AUBAIS BOISSIÈRES CODOGNAN GALLARGUES-LE-MONTUEUX MUS NAGES & SOLORGUES UCHAUD VERGÈZE VESTRIC & CANDIAC Parking de co-voiturage de Gallargues-le-Montueux COMMUNAUTE P.3 : Président et Vice-présidents de P.7 : Cap Gallargues, un projet pour la Communauté de Communes toute l’économie du territoire DE COMMUNES P.4/5 : Des travaux réalisés pour une P.8/9 : Une nouvelle digue pour sécuriser RHÔNY-VISTRE-VIDOURLE meilleure qualité de vie ! les berges du Rhôny de Vergèze 2 Avenue de la Fontanisse P.6 : Gallargues-Le-Montueux, une et Codognan aire de covoiturage nouvelle P.10 : Tarifs en déchetterie, des règles 30660 Gallargues-le-Montueux génération simplifiées et plus justes P.6 : Les mobilités alternatives sur la bonne voie… Chères concitoyennes, Chers concitoyens, L’épidémie de COVID-19 bouleverse notre vie depuis le mois de mars dernier. Certains, atteint par la maladie, l’ont perdue, et je veux assurer leur famille et leurs proches de notre affection et de notre soutien. D’autres souffrent encore des affres de ce mal, alors que les soignants, dont il faut louer encore une fois le courage et le dévouement, déploient tous leurs efforts pour les soulager. D’autres encore, voient leurs ressources se tarir du fait des perturbations éco- nomiques. Tous, nous voyons nos pratiques sociales et nos libertés contraintes, réduites, amputées. Pour atténuer ces troubles, la Communauté de Com- munes a su, grâce à l’implication de tous ses agents, assurer la continuité des services publics. L’espoir d’un avenir proche et meilleur est porté par la cam- pagne de vaccination qui débute. -

Vidourle 1 0206

n°1 Compostage de proximité Fév. 2006 Vidourle Bulletin de liaison du CIVAM du Vidourle Co-compostage collectif Convention avec la à la ferme Communauté des Communes En 2005, nous avons consolidé notre partenariat avec les Communautés des Communes du Pays du Pays de Sommières de Sommières et du Pays de Lunel. Le groupe qui Une convention a été signée entre le CIVAM du A retenir compte maintenant une quinzaine d’agriculteurs a Vidourle, la FD CIVAM du Gard et la Communauté Sommaire ● Visite de la maison HQE de Marguerittes, 23 Février 2006 à 10h00 mis a composter 600 t de matières premières (500 de Communes du Pays de Sommières. Elle prévoit Présentation des CIVAM du Gard t de déchets verts et 100 t de fumier d’ovins) ; 150 le développement du compostage de proximité (à ● Conférence débat, 24 Février 2006 à 20h30 au CART à Sommières Temps Fort : Conférence débat «La vie rurale, enjeu écologique et de société. Propositions t le seront au printemps. Les déchets verts broyés la ferme, individuel et collectif), des visites par les altermondialistes» écoles d’exploitations du réseau RACINES et Habitat Ecologique ont été mélangés au fumier, arrosés, mis en andain ● Journées : «Gestion économe et écologique de l’eau» et recouverts par une bâche géotextile. Une étude l’organisation d’actions lors de la semaine du Lutter contre les pollutions par les pesticides 19, 20 mai et 17 juin 2006 de faisabilité est en cours. Elle doit permettre de développement durable. Compostage de proximité ● Journées : «Lecture et enduis à la chaux» définir les différentes possibilités pour la structuration mi septembre 2006 d’un outil de production pérenne. -

ANNUAIRE 2020|2026 Des Maires Et Des Présidents D’EPCI Du Gard

ANNUAIRE 2020|2026 des Maires et des Présidents d’EPCI du Gard WWW.AMF30.FR ANNUAIRE DES MAIRES ET DES PRÉSIDENTS D’EPCI DU GARD 2020 | 2026 n Directeur de la publication : M. Philippe RIBOT n Rédaction : Association des Maires et des Présidents d’EPCI du Gard (AMF30) n Création, réalisation : Com’média - 4 rue Ferdinand de Lesseps - 66280 SALEILLES Tél. : 04 68 68 42 00 - Courriel : [email protected] n Couverture : Création Com’média Toute reproduction même partielle est interdite. Toute contrefaçon ou utilisation de nos modèles à des fins commerciales, publicitaires ou de support sera poursuivie (article 19 de la loi du 11 mars 1957). Nous déclinons toutes responsabilités pour toutes les erreurs involontaires qui auraient pu se glisser dans le présent document, malgré tous les soins apportés à sa réalisation (jurisprudence : cour d’appel de Toulouse 1897, cour d’appel de Paris 19 octobre 1901). 3 4 Éditorial M. Philippe RIBOT Président La sortie de l’édition 2020-2026 de l’annuaire des Maires et Présidents d’Intercommunalités du Gard est l’occasion pour moi de féliciter l’ensemble des maires et présidents d’intercommunalités, anciens ou nouveaux, pour leur engagement auprès de nos concitoyens et pour notre territoire. L’Association des Maires et des Présidents d’Intercommunalités de France et notre association départementale que j’ai l’honneur de présider, sont des interlocuteurs incontournables des services de l’État. Leur vocation est de représenter les collectivités sans distinction de taille, de sensibilité politique ou encore de leur caractère rural ou urbain. Dans une période où l’on peut légitimement s’interroger sur les moyens financiers de notre action, et dans un contexte de recentralisation rampante, nous devons être unis et solidaires pour porter la voix des territoires. -

Unités De Gestion Du Sanglier 06/11/2014 Ponteils Et Brésis ARDECHE (07) B on Ne Concoules V DROME (26) Au 3232 X Aujac Génolhac

- DEPARTEMENT DU GARD - Malon et Elze DDTM du Gard Unités de gestion du sanglier 06/11/2014 Ponteils et Brésis ARDECHE (07) B on ne Concoules v DROME (26) au 3232 x Aujac Génolhac Sénéchas A ig u è Le Garn z Bordezac Gagnières Barjac e P Laval LOZERE (48) Chambon e y Courry St Roman Chamborigaud r e m a St Julien l e Bessèges La St Brès S de Peyrolas Me St Privat de t Vernarède yr Robiac an C nes Champclos Roches- Issirac h r St Jean de i Montclus s sadoule t St Paulet Ste Cécile St Victor Maruéjols o l Salazac Molières de Caisson Portes 3131 de d d'Andorge 3131 e sur Cèze Pont St Esprit Le Martinet St Ambroix Malcap R R . St o St Jean St ch Tharaux St André de R. S 2828 e d t 2828 Florent Denis g e L de ud Méjannes le Clap a Branoux sur A. e C u Carsan a r Valériscle Les r e St Alexandre les La Grand n n Mages o t Taillades Combe Potelières Cornillon ls Rivières Laval St Julien Goudargues el Pradel h t de C. c e L z St Nazaire a St Mi u St Les Salles Allègre t E Vénéjan m La Roque S ' e Julien d Gervais lo du Gardon Rousson sur Cèze u les Fons z St Etienne e 2222 Rosiers sur Lussan des Sorts Soustelle 2222 St André St Martin Bagnols 2323 Lussan Verfeuil d'Olérargues 2727 de 2323 Navacelles sur Cèze Salindres 2424 Chusclan Valgalgues Sabran St Paul Servas Cendras Bouquet VAUCLUSE (84) la Coste St Marcel St André de Valborgne Les Orsan St Privat des Vieux Plans de Careiret Brouzet les Alès 2525 Codolet F 2525 S t Vallérargues o d S n St Laurent 'A é Alès t Cavillargues Mons a Tresques Mialet ig b r la Vernède 2020 a è Lanuéjols 2020 r -

500 Ans De Protestantisme Entre Cévennes Et Méditerranée

fait vibrer la culture 500 ans de protestantisme entre Cévennes et Méditerranée en réseau AVRIL 2017 DECEMBRE 2018 C’est dans le cadre des commémorations internationales concernant "l’année LUTHER 2017, 500e anniversaire de la Réforme" que le Département du Gard a choisi de s’associer à cet événement organisé par le Pays Vidourle Camargue, pour valoriser et faire connaitre le patrimoine protestant. Le Gard représente à lui seul le quart des protestants de France. Les archives départementales disposent d’importants fonds. Le sud du département et la Petite Camargue possèdent un riche patrimoine bâti protestant, en cours d’inventaire Coordination et de rénovation sur ce et médiation : Pays qui comprend la baie Patricia Carlier Mission patrimoine d’Aigues-Mortes. Pays Vidourle Camargue À cette occasion les communes [email protected] du Pays possédant des temples 04 34 14 80 00 ont souhaité s’associer aux partenaires du réseau pour Communication : proposer aux visiteurs des Département du Gard / Pays Vidourle Camargue / expositions complétées Centre des Monuments d’animations, spectacles, Nationaux concerts, conférences, ateliers pédagogiques en divers lieux de notre Département entre Cévennes et Méditerranée. 2 Sommaire AIGUES-MORTES 4 AIGUES-VIVES 6 AUBAIS 6 BEAUVOISIN 6 CALVISSON 7 CANNES-et-CLAIRAN 8 CODOGNAN 8 CONGENIES 8 GALLARGUES-LE-MONTUEUX 9 JUNAS 9 LUNEL 10 MARSILLARGUES 12 MIALET 12 MONTPEZAT 13 MUS 13 NIMES 14 SAINT-LAURENT-D’ AIGOUZE 15 SALINELLES 15 SOMMIERES 18 UCHAUD 19 VAUVERT 20 VESTRIC-et-CANDIAC 20 CONFERENCES 21 3 Aigues-Mortes Salle des Capucins - Place Saint-Louis Du 8 au 23 avril 2017 Le patrimoine protestant de Vaunage et de Petite Camargue. -

Le Père Noël Passera Bien À Calvisson !

20 Décembre Décembre 20 Confinement (ou pas) le Père Noël passera bien à Calvisson ! Bien vivre à 20 VIE DE LA COMMUNE décembre 20 3 en bref… Sommaire dernière minute page Le mot 2 En bref 3 Le mot du Maire Info-Flash Don du sang du Maire VIE DE LA COMMUNE l'information locale Prochaine collecte Elle aura lieu le 16 décembre 4 Le conseil municipal en temps réel Les délégués communautaires au foyer communal de 9 h à 19 h 30. Malgré les mesures de confinement l'EFS a 5 Cest voté / CMJ appelé les citoyens, sauf ceux présentant Chères Calvissonnaises, chers Calvissonnais Conseil des Sages des symptômes grippaux, à se rendre dans 6 Démarches administratives les centres de collecte, qu'ils soient fixes ou Vous l’avez remarqué en page de couverture, Des travaux de réfection des voiries et de mobiles. 6-7 C'est en cours le Père Noël va bien passer à Calvisson. trottoirs sont en cours ou vont démarrer : Un déplacement autorisé "au motif de l'assis- C’est une image symbolique pour nous • réfection totale de l’assainissement, des 8-9 Embellissement du village tance aux personnes les plus vulnérables", une En travaux encourager à aller de l’avant. Nous traversons routes et des trottoirs du plus vieux case à cocher sur l'attestation de déplacement cette crise sanitaire et économique sans lotissement de Calvisson, Font Vinouse, 10-11 Sports et Loisirs dérogatoire. précédent mais nous devons rester optimistes • transformation de la départementale 107, 12-15 Enfance, éducation et sommes persuadés que nous allons vivre chemin de la Dale et avenue de Gerbu, Déplacement des jours meilleurs. -

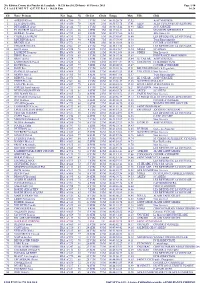

20E Edition Course Des Pinèdes De Langlade - 10.320 Km (10.320 Kms) - 01 Février 2015 Page 1/10 C L a S S E M E N T G E N E R a L - 10.320 Kms 14:24

20e Edition Course des Pinèdes de Langlade - 10.320 km (10.320 kms) - 01 Février 2015 Page 1/10 C L A S S E M E N T G E N E R A L - 10.320 Kms 14:24 Clt Nom - Prénom Nat Doss. Né Clt Cat Clt Sx Temps Moy. Ville Club 1 AGRINIER Eric FRAn°780 71 1V1M 1M 00:35:20.74 17.52 ASSP VERGEZE 2 EL HADAFE ADIL FRA n°050 78 1 SEM 2 M 00:35:33.75 17.41 ALES ALES CEVENNES ATHLETISME 3 DEVARIEUX pierre FRAn°326 75 2V1M 3M 00:36:34.44 16.93 ALES ACN ANDUZE 4 EL GOURCH Abdelmajid FRAn°821 86 2SEM 4M 00:37:16.23 16.61 MANDUEL METROPOLE 5 HERBAU Nicolas FRAn°725 82 3SEM 5M 00:37:27.60 16.53 Athletismes 30 6 CHEREL LAURENT FRAn°183 72 3V1M 6M 00:37:45.47 16.40 LES BIPEDES DE LA VAUNAGE 7 MAURIN Mickaël FRAn°699 90 4SEM 7M 00:37:59.80 16.30 Team Runstoppable 8 BRUNEL Karl FRAn°773 93 1ESM 8M 00:38:10.66 16.22 COURIR A VAUVERT 9 CHALIER GILLES FRAn°501 69 4V1M 9M 00:38:17.53 16.17 LES BIPEDES DE LA VAUNAGE 10 BLOT alexis FRAn°224 93 2ESM 10M 00:38:21.67 16.14 ARLES SC ARLES 11 LAURENT François FRAn°476 89 5SEM 11M 00:38:21.68 16.14 NÎMES Non Licencié 12 PIBOU Florent FRAn°558 69 5V1M 12M 00:38:57.48 15.89 ENDURANCE SHOP NIMES 13 BRUC olivier FRAn°374 77 6SEM 13M 00:39:05.85 15.84 LE CAILAR ASSP VERGEZE 14 LAMOUROUX Pascal FRAn°628 62 1V2M 14M 00:39:17.37 15.76 TARASCON FC BARBENTANE 15 ROVINI Steve FRAn°025 77 7SEM 15M 00:40:00.90 15.47 COURIR A VERGEZE 16 RAVE Eric FRAn°353 73 6V1M 16M 00:40:10.16 15.41 BELLEGARDE foulée bellegardaise 17 PLANELLES raphael FRAn°466 95 3ESM 17M 00:40:11.55 15.41 VILLETELLE Non Licencié 18 MORIN Franck FRAn°705 90 8SEM 18M 00:40:17.96