Operation-Belcarra-Report-2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Official Parliamentary Delegation

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Report of the Official Parliamentary Delegation Visit to Papua New Guinea and East Timor October – November 2008 December 2008 © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 ISBN 978-1-74229-021-8 This document was prepared by the Parliamentary Education Office and printed by the Printing and Delivery Services section of the Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. ii Contents Preface ..........................................................................................1 Membership of the Delegation ....................................................4 1 Introduction ......................................................................... 5 Objectives ............................................................................................5 Acknowledgments ...............................................................................6 Papua New Guinea – background information ...................................13 East Timor – background information .................................................16 2 Delegation visit to Papua New Guinea ................................ 21 Strengthening ties between Australian and PNG Parliaments .............21 Meetings with Government ......................................................................... 21 Parliament-to-Parliament ties ...................................................................... 23 Strongim Gavman Program .......................................................................... 23 Contemporary political, economic -

![Chapter [No.]: [Chapter Title]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5667/chapter-no-chapter-title-415667.webp)

Chapter [No.]: [Chapter Title]

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Doing Time - Time for Doing Indigenous youth in the criminal justice system House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs June 2011 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 ISBN 978-0-642-79266-2 (Printed version) ISBN 978-0-642-79267-9 (HTML version) Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................. ix Membership of the Committee ............................................................................................................ xi Terms of reference ............................................................................................................................ xiii List of acronyms ................................................................................................................................. xv List of recommendations ................................................................................................................... xix 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 Conduct of the inquiry .............................................................................................................. 2 Structure of the report .............................................................................................................. 4 2 Indigenous youth and the criminal justice system: an overview .................... -

Raptor Rescue: ""The End of the Line" Vet Check: Psittacine Beak And

Official Newsletter ofWildcare AustraliaAus WILDWinter 2010 Issue 57 NEWS Raptor Rescue: ""The End of the Line" Vet Check: Psittacine Beak and Feather Disease This newsletter is proudly sponsored by Brett Raguse, MP Federal Member for Forde. COVER PHOTO// R. GooNAN NEWS & ACTIVITIES Karen Scott President’sWELL, ANOTHER WILDCARE YEAR HAS COME member Report. positions so hopefully this will help AND GONE with our Annual General Meeting the work load of the existing committee (AGM) being held in late June. Many thanks members. to the members who took the time to attend and to those who submitted their Proxy votes I would also like to say a special thank you but couldn’t attend. It was nice to catch up to our wonderful secretary Tracy who, whilst with everyone and see some familiar faces. juggling long hours at work, still managed to organise the AGM and all of the necessary I would like to say a huge thank you to the mail-outs that needed to be sent. Thank you, Wildcare Management Committee for all of Tracy. their hard work in the past year. It has been a difficult year with juggling family, work, I hope that everyone is enjoying the “quieter study, rescues and rehabilitating; I know season” – enjoy it while it lasts! I am sure that everyone has worked very hard to keep that spring will be here before we know it. Wildcare operational. This year the Management Committee has been extended to include six committee A Warm Welcome to Our New Members Wildcare Australia welcomes the following new members: Coral Johnson, Advancetown; Christine Johnes -

Blair (ALP 8.0%)

Blair (ALP 8.0%) Location South east Queensland. Blair includes the towns of Ipswich, Rosewood, Esk, Kilcoy and surrounding rural areas. Redistribution Gains Karana Downs from Ryan, reducing the margin from 8.9% to 8% History Blair was created in 1998. Its first member was Liberal Cameron Thompson, who was a backbencher for his entire parliamentary career. Thompson was defeated in 2007 by Shayne Neumann. History Shayne Neumann- ALP: Before entering parliament, Neumann was a lawyer. He was a parliamentary secretary in the Gillard Government and is currently Shadow Minister for Immigration. Robert Shearman- LNP: Michelle Duncan- Greens: Sharon Bell- One Nation: Bell is an estimating assistant in the construction industry. Majella Zimpel- UAP: Zimpel works in social services. Simone Karandrews- Independent: Karandrews is a health professional who worked at Ipswich Hospital. John Turner- Independent: Peter Fitzpatrick- Conservative National (Anning): John Quinn- Labour DLP: Electoral Geography Labor performs best in and around Ipswich while the LNP does better in the small rural booths. Labor’s vote ranged from 39.37% at Mount Kilcoy State School to 76.25% at Riverview state school near Ipswich. Prognosis Labor should hold on to Blair quite easily. Bonner (LNP 3.4%) Location Eastern suburbs of Brisbane. Bonner includes the suburbs of Mount Gravatt, Mansfield, Carindale, Wynnum, and Manly. Bonner also includes Moreton Island. Redistribution Unchanged History Bonner was created in 2004 and has always been a marginal seat. Its first member was Liberal Ross Vasta, who held it for one term before being defeated by Labor’s Kerry Rea. Rea only held Bonner for one term before being defeated by Vasta, running for the LNP. -

MICHAEL BERKMAN MP Queensland Greens Member for Maiwar

MICHAEL BERKMAN MP Queensland Greens Member for Maiwar 31 October 2018 Hon Mark Bailey MP Minister for Transport and Main Roads GPO Box 2644 BRISBANE QLD 4001 Via email: [email protected] Dear Minister Bailey, I am writing to convey concerns expressed by one of my constituents in relation to the roundabout that connects Boundary Road, Rouen Road and Rainworth Road. I understand that, given this is a State controlled road forming part of the regional road network, some issues such as crossings and signage may overlap State and local government jurisdiction. Accordingly, I am contacting both you and Paddington Ward Councillor Peter Matic to request assistance addressing the concerns outlined below, in the hope that this matter may be resolved quickly. I understand from my constituent, James, that cars frequently speed through the roundabout, either ignoring or unaware of the pedestrian crossing. James tells me he recently had a near-miss incident at the roundabout while pushing his 8 week old daughter in her pram; two cars rapidly passed through the roundabout, apparently unaware of him standing and waiting at the edge of the crossing. He believes that if he had exercised the right of way afforded by the pedestrian crossing, he and his daughter could have been seriously injured. Locals also tell me there are other issues with traffic along Boundary and Rouen Roads in that residential area, and in particular trucks frequently using their engine brake systems. Are you able to advise whether there are any existing plans to upgrade roads or improve signage in this area, or to undertake other traffic management strategies to accommodate this growing residential community? I would also request that your department: 1. -

Electorate Changes" Appendix 5) That Being Moved from Division Is a Regional Interest Disadvantage

The Federal Redistribution 2009 QUEENSLAND Objection Number 532 Michael O’Dwyer State Director LNP 50 pages for a new Queensland 21 August 2009 Mr Ed Killesteyn Electoral Commissioner Redistribution Committee for Queensland 7th Floor 488 Queen Street Brisbane Qld 4001 Facsimile: (07) 3834 3452 Email: [email protected] Dear Mr Killesteyn, The Liberal National Party (The LNP) responds to the Red istribution Committee for Queensland's invitation under Section 69 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 for objections to the proposed redistribution of Queensland into electoral divisions. Our submission is attached . Thank you for your consideration of our submission. Yours sincerely Michael O'Dwyer State Director LNP Headquarters: Po Box 5156, West End. Qld 4101 T, (07) 3B44 0666 F, (07) 3B44 03B6 E, [email protected] w. www.lnp.org.au CONTENTS Letter Contents 1 Summary 2 1. Introduction 3 2. Context 3-5 3 RCQ's General Strategy 5 -7 Specific Objections 8-29 4. South East Queen sland South Divisions 8 - 10 5. South East Queensland North Divisions 11-18 6 Country Divisions 19 - 29 7 Name of new division 29 Appendices 30 - 39 --0000000-- 1 Summary The Liberal National Party's (LNP) objections are underpinned by our belief that the essence of democracy includes fair representation for all electors - metropolitan, rural, regional and remote parts of Queensland. The LNP has examined the proposed electoral divisions, consulted with industry groups, local governments, regional councils and individual electors and submits the following objections and comments. The LNPs specific objections fall into two categories : • Structural unfairness that destroys community of interest resulting in an unrepresentative outcome; and • Community of interest dislocations in specific proposed electoral divisions. -

Maiden Speech

Speech By Michael Berkman MEMBER FOR MAIWAR Record of Proceedings, 22 March 2018 MAIDEN SPEECH Mr BERKMAN (Maiwar—Grn) (4.52 pm): I begin, as so many have done before me, by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet—the Jagera and Turrbal people— and their ancient culture, traditions and lore. I stand here on their land and acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty has never been ceded—that this parliament sits on stolen land. If we are to make amends for the colonisation and the dispossession and genocide of the last 230 years—and we should—clear recognition of first nations’ sovereignty and the negotiation of treaties with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples must be a priority for our state, country and community. I pay my respects to elders past and present and I thank them for their ongoing custodianship of this vast and unique continent. I lament that since invasion we have not only disrupted your connection to country but fallen far short of following your example and fulfilling our duty to care for this land and preserve it for future generations. It was a great honour to have local elder Uncle Des Sandy attend as my guest for the opening of this parliament. We discussed that I was not only the first member of the Queensland Greens to be elected to this chamber but also the inaugural member for the newly created seat of Maiwar. He asked me a question that surprised me: ‘What does Maiwar mean?’ As I understood it, Maiwar was the local Indigenous people’s name for what we now call the Brisbane River, but Uncle Des’s response spoke volumes to me about the depth of his understanding of and connection to his country and just how much we have to learn from our first nations people. -

ACA Qld 2019 National Conference

➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ ➢ • • • • • • • • • • • • • Equal Remuneration Order (and Work Value Case) • 4 yearly review of Modern Awards • Family friendly working conditions (ACA Qld significant involvement) • Casual clauses added to Modern Awards • Minimum wage increase – 3.5% • Employment walk offs, strikes • ACA is pursuing two substantive claims, • To provide employers with greater flexibility to change rosters other than with 7 days notice. • To allow ordinary hours to be worked before 6.00am or after 6.30pm. • • • • • Electorate Sitting Member Opposition Capricornia Michelle Landry [email protected] Russell Robertson Russell.Robertson@quee nslandlabor.org Forde Bert Van Manen [email protected] Des Hardman Des.Hardman@queenslan dlabor.org Petrie Luke Howarth [email protected] Corinne Mulholland Corinne.Mulholland@que enslandlabor.org Dickson Peter Dutton [email protected] Ali France Ali.France@queenslandla bor.org Dawson George Christensen [email protected] Belinda Hassan Belinda.Hassan@queensl .au andlabor.org Bonner Ross Vasta [email protected] Jo Briskey Jo.Briskey@queenslandla bor.org Leichhardt Warren Entsch [email protected] Elida Faith Elida.Faith@queenslandla bor.org Brisbane Trevor Evans [email protected] Paul Newbury paul.newbury@queenslan dlabor.org Bowman Andrew Laming [email protected] Tom Baster tom.Baster@queenslandla bor.org Wide Bay Llew O’Brien [email protected] Ryan Jane Prentice [email protected] Peter Cossar peter.cossar@queensland -

January 2008

EMERGENCY WILDLIFE PHONE SERVICE - 07 5527 2444 (24 X 7) EDUCATION WILDLIFE REHABILITATION RESCUE Summer 2007/2008, Issue 47 WILDNEWS The Newsletter of the Australian Koala Hospital Association Inc. - WILDCARE AUSTRALIA This newsletter is proudly sponsored by BRETT RAGUSE MP FEDERAL MEMBER FOR FORDE Australian Koala Hospital Association Inc. Wildcare Australia Page 1 Veterinarian - Dr. Jon Hanger 1300 369 652 Wildcare Australia Office 07 5527 2444 (8am to 4pm weekdays) Wildcare Education and Training 07 5527 2444 Website: www.wildcare.org.au Email: enquiries@ wildcare.org.au P.O. Box 2379, Nerang Mail Centre, Queensland 4211 INTERNATIONAL PATRON : Brigitte Bardot AUSTRALIAN PATRON: Helen Clarke IN THIS ISSUE: MAIN COMMITTEE President’s Report 3 President Gail Gipp From the Office 4 Vice-President Karen Scott Wildlife Phone Service 5 Secretary Trish Hales Assistant Secretary Dianna Smith Coordinator’s Corner 6 - 7 Keeping the Dream Alive 8 - 9 Minutes Secretary Laura Reeder Official Business 10 Treasurer Kirsty Arnold Research and Wildcare 11 Education Karen Scott Kathryn Biber Species Spotlight: Whales 12 Kim Alexander Record Keeper Renée Rivard Rescue Stories 13 On the Lighter Side 14 Assistant Record Kiersten Jones Keeper PJ’s Wildcare for Kids 15 - 16 Newsletter Eleanor Hanger Renée Rivard Photo Gallery 17 SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY SUBCOMMITTEE New Members 18 Prof. T. Heath Dr D. Sutton Supporters 19 - 20 Prof. W. Robinson Dr C. Pollitt Dr R. Kelly Dr A. Tribe LEGAL ADVISER PHOTOGRAPHS Mr I. Hanger Q.C. T. Eather E.M. Hanger HONORARY J. Hanger SOLICITOR L. Meffan Position Vacant K. Remmert R. Rivard D. Smith T. Wimberley SUBMISSIONS If you are interested in submitting an article or photograph for inclusion in the next newsletter, please submit via the Wildcare Australia email address, subject “Wildnews”, before 30th March 2008 The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of WILDCARE AUSTRALIA or of the editor. -

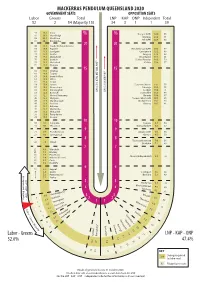

KAP ONP Independent Total 52 2 54 (Majority 15) 34 3 1 1 39

MACKERRAS PENDULUM QUEENSLAND 2020 GOVERNMENT SEATS OPPOSITION SEATS Labor Greens Total LNP KAP ONP Independent Total 52 2 54 (Majority 15) 34 3 1 1 39 93 28.2 Inala Traeger (KAP) 24.8 93 91 26.3 Woodridge % % Warrego 23.2 91 89 23.5 Gladstone Hill (KAP) 22.6 89 87 20.7 Bundamba 20 20 85 18.5 South Brisbane (Greens) 83 17.8 Algester Hinchinbrook (KAP) 19.3 87 81 17.3 Sandgate Condamine 19.2 85 79 17.1 Jordan Gregory 17.3 83 77 16.8 Morayfield Broadwater 16.6 81 75 16.6 Ipswich Surfers Paradise 16.3 79 73 16.1 Waterford Callide 15.9 77 71 15.1 Nudgee 15 15 69 14.9 Stretton 67 14.6 Toohey 65 14.4 Ipswich West 63 13.9 Miller 61 13.4 Logan 59 13.4 Lytton Southern Downs 14.1 75 57 13.2 Greenslopes Nanango 12.3 73 55 13.2 Kurwongbah Lockyer 11.6 71 53 12.8 Bancroft PARTY LIBERAL NATIONAL TO SWING LABOR PARTY TO SWING Scenic Rim 11.5 69 51 12.7 Mount Ommaney Burnett 10.8 67 49 12.3 Mulgrave Toowoomba South 10.3 65 47 11.9 Maryborough Mudgeeraba 10.1 63 45 11.9 Stafford Bonney 10.1 61 43 11.4 Bulimba 41 11.4 Murrumba 39 11.1 McConnel 37 11.0 Ferny Grove 35 10.5 Cooper 10 10 33 9.9 Capalaba Kawana 9.4 59 31 9.6 Macalister Maroochydore 9.2 57 9 9 29 8.7 Rockhampton Mirani (ONP) 9.0 55 27 8.3 Springwood Gympie 8.5 53 8 8 Toowoomba North 7.4 51 25 7.8 Gaven Burdekin 7.1 49 7 7 23 6.8 Mansfield 21 6.8 Mackay 19 6.7 Pine Rivers Noosa (Independent) 6.9 47 17 6.4 Maiwar (Greens) 15 6.3 Cook 13 6.2 Redcliffe 6 6 11 5.7 Keppel 9 5.6 Cairns Southport 5.5 45 Buderim 5.3 43 Independent Majority 7 5.3 Pumicestone* 5 5.2 Aspley LNP - KAP - ONP - 5 5 Oodgeroo -

List of Senators

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 19.1 – 20 September 2021 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office details & email address Parliament House State/Territory telephone & fax 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW 334A Marrickville Road, Fax: (02) 6277 8562 Marrickville NSW 2204 (PO Box 5100, Marrickville NSW 2204) Tel: (02) 9564 3588, Fax: (02) 9564 1734 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Fax: (02) 6277 8581 (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Tel: (02) 9869 4288, Fax: (02) 9869 4833 3. Allen, Dr Katrina Jane (Katie) Higgins, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 Tel: (03) 9822 4422 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, Fax: (02) 6277 8526 168 Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel: (08) 9409 4517 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 7860 Minister for Home Affairs QLD Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227 (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel: (07) 5580 9111, Fax: (07) 5580 9700 6. Andrews, The Hon Kevin James Menzies, LP Email: [email protected] Tel: (02) 6277 4023 VIC 1st Floor 651-653 Doncaster Road, Fax: (02) 6277 4074 Doncaster VIC 3108 (PO Box 124, Doncaster VIC 3108) Tel: (03) 9848 9900, Fax: (03) 9848 2741 7. -

Youth Justice and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021

LEGAL AFFAIRS AND SAFETY COMMITTEE Members present: Mr PS Russo MP—Chair Ms SL Bolton MP Ms JM Bush MP Mrs LJ Gerber MP Mr JE Hunt MP Mr AC Powell MP Mr JM Krause MP Member in attendance: Mr MC Berkman MP Staff present: Ms R Easten—Committee Secretary Ms K Longworth—Assistant Committee Secretary Ms M Telford—Assistant Committee Secretary PUBLIC HEARING—INQUIRY INTO THE YOUTH JUSTICE AND OTHER LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2021 TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS MONDAY, 22 MARCH 2021 Brisbane Public Hearing—Inquiry into the Youth Justice and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021 MONDAY, 22 MARCH 2021 ____________ The committee met at 8.46 am. CHAIR: Good morning. I declare open the public hearing for the Legal Affairs and Safety Committee’s inquiry into the Youth Justice and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021. I would like to respectfully acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet today and pay our respects to elders past and present. We are very fortunate to live in a country with two of the oldest continuing cultures in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, whose lands, winds and waters we all share. On 25 February 2021 the Hon. Mark Ryan MP, Minister for Police and Corrective Services and Minister for Fire and Emergency Services, introduced the Youth Justice and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021 to the parliament and referred it to the Legal Affairs and Safety Committee for examination. My name is Peter Russo, member for Toohey and chair of the committee. The other committee members here with me today are: Mrs Laura Gerber, member for Currumbin and deputy chair; Ms Sandy Bolton, member for Noosa; Ms Jonty Bush, member for Cooper; Mr Jason Hunt, member for Caloundra; and Andrew Powell, member for Glass House, for whom Jon Krause, member for Scenic Rim will be substituting later on today.