Youth Justice and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operation-Belcarra-Report-2017.Pdf

October 2017 Operation Belcarra A blueprint for integrity and addressing corruption risk in local government October 2017 Operation Belcarra A blueprint for integrity and addressing corruption risk in local government © The State of Queensland (Crime and Corruption Commission) (CCC) 2017 You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland, Crime and Corruption Commission as the source of the publication. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (BY) 4.0 Australia licence. To view this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from the CCC, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. For permissions beyond the scope of this licence contact: [email protected] Disclaimer of Liability While every effort is made to ensure that accurate information is disseminated through this medium, the Crime and Corruption Commission makes no representation about the content and suitability of this information for any purpose. The information provided is only intended to increase awareness and provide general information on the topic. It does not constitute legal advice. The Crime and Corruption Commission does not accept responsibility for any actions undertaken based on the information contained herein. ISBN 978-1-876986-85-8 Crime and Corruption Commission GPO Box 3123, Brisbane QLD 4001 Phone: 07 3360 6060 (toll-free outside Brisbane: 1800 061 611) Level 2, North Tower Green Square Fax: 07 3360 6333 515 St Pauls Terrace Email: [email protected] Fortitude Valley QLD 4006 Note: This publication is accessible through the CCC website <www.ccc.qld.gov.au>. -

MICHAEL BERKMAN MP Queensland Greens Member for Maiwar

MICHAEL BERKMAN MP Queensland Greens Member for Maiwar 31 October 2018 Hon Mark Bailey MP Minister for Transport and Main Roads GPO Box 2644 BRISBANE QLD 4001 Via email: [email protected] Dear Minister Bailey, I am writing to convey concerns expressed by one of my constituents in relation to the roundabout that connects Boundary Road, Rouen Road and Rainworth Road. I understand that, given this is a State controlled road forming part of the regional road network, some issues such as crossings and signage may overlap State and local government jurisdiction. Accordingly, I am contacting both you and Paddington Ward Councillor Peter Matic to request assistance addressing the concerns outlined below, in the hope that this matter may be resolved quickly. I understand from my constituent, James, that cars frequently speed through the roundabout, either ignoring or unaware of the pedestrian crossing. James tells me he recently had a near-miss incident at the roundabout while pushing his 8 week old daughter in her pram; two cars rapidly passed through the roundabout, apparently unaware of him standing and waiting at the edge of the crossing. He believes that if he had exercised the right of way afforded by the pedestrian crossing, he and his daughter could have been seriously injured. Locals also tell me there are other issues with traffic along Boundary and Rouen Roads in that residential area, and in particular trucks frequently using their engine brake systems. Are you able to advise whether there are any existing plans to upgrade roads or improve signage in this area, or to undertake other traffic management strategies to accommodate this growing residential community? I would also request that your department: 1. -

Maiden Speech

Speech By Michael Berkman MEMBER FOR MAIWAR Record of Proceedings, 22 March 2018 MAIDEN SPEECH Mr BERKMAN (Maiwar—Grn) (4.52 pm): I begin, as so many have done before me, by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet—the Jagera and Turrbal people— and their ancient culture, traditions and lore. I stand here on their land and acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty has never been ceded—that this parliament sits on stolen land. If we are to make amends for the colonisation and the dispossession and genocide of the last 230 years—and we should—clear recognition of first nations’ sovereignty and the negotiation of treaties with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples must be a priority for our state, country and community. I pay my respects to elders past and present and I thank them for their ongoing custodianship of this vast and unique continent. I lament that since invasion we have not only disrupted your connection to country but fallen far short of following your example and fulfilling our duty to care for this land and preserve it for future generations. It was a great honour to have local elder Uncle Des Sandy attend as my guest for the opening of this parliament. We discussed that I was not only the first member of the Queensland Greens to be elected to this chamber but also the inaugural member for the newly created seat of Maiwar. He asked me a question that surprised me: ‘What does Maiwar mean?’ As I understood it, Maiwar was the local Indigenous people’s name for what we now call the Brisbane River, but Uncle Des’s response spoke volumes to me about the depth of his understanding of and connection to his country and just how much we have to learn from our first nations people. -

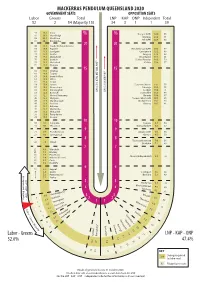

KAP ONP Independent Total 52 2 54 (Majority 15) 34 3 1 1 39

MACKERRAS PENDULUM QUEENSLAND 2020 GOVERNMENT SEATS OPPOSITION SEATS Labor Greens Total LNP KAP ONP Independent Total 52 2 54 (Majority 15) 34 3 1 1 39 93 28.2 Inala Traeger (KAP) 24.8 93 91 26.3 Woodridge % % Warrego 23.2 91 89 23.5 Gladstone Hill (KAP) 22.6 89 87 20.7 Bundamba 20 20 85 18.5 South Brisbane (Greens) 83 17.8 Algester Hinchinbrook (KAP) 19.3 87 81 17.3 Sandgate Condamine 19.2 85 79 17.1 Jordan Gregory 17.3 83 77 16.8 Morayfield Broadwater 16.6 81 75 16.6 Ipswich Surfers Paradise 16.3 79 73 16.1 Waterford Callide 15.9 77 71 15.1 Nudgee 15 15 69 14.9 Stretton 67 14.6 Toohey 65 14.4 Ipswich West 63 13.9 Miller 61 13.4 Logan 59 13.4 Lytton Southern Downs 14.1 75 57 13.2 Greenslopes Nanango 12.3 73 55 13.2 Kurwongbah Lockyer 11.6 71 53 12.8 Bancroft PARTY LIBERAL NATIONAL TO SWING LABOR PARTY TO SWING Scenic Rim 11.5 69 51 12.7 Mount Ommaney Burnett 10.8 67 49 12.3 Mulgrave Toowoomba South 10.3 65 47 11.9 Maryborough Mudgeeraba 10.1 63 45 11.9 Stafford Bonney 10.1 61 43 11.4 Bulimba 41 11.4 Murrumba 39 11.1 McConnel 37 11.0 Ferny Grove 35 10.5 Cooper 10 10 33 9.9 Capalaba Kawana 9.4 59 31 9.6 Macalister Maroochydore 9.2 57 9 9 29 8.7 Rockhampton Mirani (ONP) 9.0 55 27 8.3 Springwood Gympie 8.5 53 8 8 Toowoomba North 7.4 51 25 7.8 Gaven Burdekin 7.1 49 7 7 23 6.8 Mansfield 21 6.8 Mackay 19 6.7 Pine Rivers Noosa (Independent) 6.9 47 17 6.4 Maiwar (Greens) 15 6.3 Cook 13 6.2 Redcliffe 6 6 11 5.7 Keppel 9 5.6 Cairns Southport 5.5 45 Buderim 5.3 43 Independent Majority 7 5.3 Pumicestone* 5 5.2 Aspley LNP - KAP - ONP - 5 5 Oodgeroo -

1000 Referral to Health, Communities, Disability Services and Domestic and Family Violence Prevention Committee

ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/work-of-assembly/hansard Email: [email protected] Phone (07) 3553 6344 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT Thursday, 3 May 2018 Subject Page SPEAKER’S STATEMENT ................................................................................................................................................... 949 Questions Without Notice ................................................................................................................................. 949 REPORT................................................................................................................................................................................ 949 Auditor-General ................................................................................................................................................. 949 Tabled paper: Auditor-General of Queensland: Report to Parliament No. 14: 2017-18— The National Disability Insurance Scheme. ....................................................................................... 949 MINISTERIAL STATEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 949 Ipswich City Council ......................................................................................................................................... 949 Ipswich City Council ........................................................................................................................................ -

August 2020 Meeting Minutes Confirmed

MINUTES OF THE ORDINARY MEETING OF THE TORRES SHIRE COUNCIL HELD IN COUNCIL CHAMBERS ON THURSDAY ISLAND, TUESDAY, 18 AUGUST 2020 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PRESENT Mayor Vonda Malone (Chair), Cr. Gabriel Bani (Deputy Mayor), Cr. Thomas Loban, Cr. John Abednego, Dalassa Yorkston (Chief Executive Officer), Shane Whitten (Director Corporate and Community Services), Maxwell Duncan (Director Governance and Planning Services), Edward Kulpa (A/Director Engineering and Infrastructure Services), and Ethel Mosby (Executive Assistant) The meeting opened with a prayer by Deputy Mayor Bani at 9:11am. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Mayor Malone acknowledged the traditional owners the Kaurareg people and all Torres Strait island elders past, present and emerging. CONDOLENCES a minute of silence was held for: Mr Horace Baira (snr) (Badu Island) Mr Stephen Matthew (snr) Mr Joe Reuben Mr Robert Edward Sailor Ms Evelyn Levi-Lowah Mrs Sharon Sabatino Mayor Malone, on behalf of Council, extended deepest condolences to the families of the loved ones who have passed. The Mayor advised Councillors that a deputation involving Hon. Warren Entsch, Member for Leichhardt was occurring at the Council Meeting today at 11am. APOLOGY An apology was received from Cr. Allan Ketchell who was unable to attend the meeting. Min. 20/8/1 Moved Cr. Loban, Seconded Deputy Mayor Bani “That Council receive the apology received from Cr. Allan Ketchell. Carried DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST UNDER THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT Mayor Malone – CEO Report – Indigenous Affairs Committee – Food pricing and food security in remote communities – Invitation to attenfd a public hearing on 19 Auguts 2020 Cr. Abednego – CEO Report – Torres Strait Regional Governance – Wednesday 12 August 2020 Cr. -

Economics and Governance Committee, Reports No. 10 and 11, 56Th Parliament, 2018-19 Budget Estimates

2018-19 Budget Estimates Volume of Additional Information Reports No. 10 and 11, 56th Parliament Economics and Governance Committee August 2018 Table of Contents Minutes of Estimates meetings Correspondence regarding leave to participate in the hearing Questions on notice and responses Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Questions on notice and responses Premier and Minister for the Trade Questions on notice and responses Deputy Premier, Treasurer and Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships Questions on notice and responses Minister for Local Government, Minister for Racing and Minister for Multicultural Affairs Answers to questions taken on notice at the hearing 24 July 2018 Documents tabled at the hearing 24 July 2018 Correspondence clarifying comments made at the hearing Minutes of Estimates meetings Minutes of Estimates meetings 1. Monday 11 June 2018 2. Friday 15 June 2018 3. Tuesday 24 July 2018 4. Tuesday 24 July 2018 5. Tuesday 24 July 2018 6. Tuesday 26 July 2018 7. Monday 30 July 2018 8. Wednesday 15 August 2018 Correspondence regarding leave to participate in the hearing Correspondence 1. 22 June 2018 – Letter from Deb Frecklingon MP, Leader of the Opposition and Shadow Minister for Trade 2. 28 June 2018 – Letter from Sandy Bolton MP, Member for Noosa 3. 12 July 2018 – Letter from Stephen Andrew MP, Member for Mirani 4. 18 July 2018 – Letter from Michael Berkman MP, Member for Maiwar 5. 20 July 2018 – Letter from Deb Frecklingon MP, Leader of the Opposition and Shadow Minister for Trade 22 June 2018 Economics and Governance Committee Attention: Mr Linus Power MP, Chair By email: [email protected] Dear Mr Power I’m writing in relation to the Committee’s consideration of the 2018/19 portfolio budget estimates. -

VAD Law Reform Hangs in the Balance STATEMENT by the MY LIFE MY Sound Evidence for VAD Laws, CHOICE COALITION PARTNERS: What We Asked

MY LIFE MY CHOICE QUEENSLAND STATE ELECTION CANDIDATES’ ATTITUDES TO VOLUNTARY ASSISTED DYING 19 OCTOBER 2020 VAD law reform hangs in the balance STATEMENT BY THE MY LIFE MY sound evidence for VAD laws, CHOICE COALITION PARTNERS: What we asked...... would be invaluable to any future debate. So too would the This report canvasses the results other Health Committee MPs of a survey by the My Life My The My Life My Choice partners asked candidates two questions who supported the majority Choice coalition which attempted findings: Joan Pease (Lytton); to determine the strength of to record attitudes to voluntary Michael Berkman (Maiwar); and their support for voluntary assisted dying (VAD) law reform Barry O’Rourke (Rockhampton). assisted dying. held by close to 600 candidates it is too late after polls close for standing at the 31 October Our belief in the value of having voters to discover that their MP QUESTION 1: Do you, as a Queensland election. present in parliament MPs for 2020-2024 will not support a matter of principle support involved in an inquiry into Several factors mean the survey VAD Bill. the right of Queenslanders matters of vital public policy is to have the choice of had a less than full response. We The passage of any VAD Bill will validated by an examination of seeking access to a system recognise that candidates can be depend on having a majority the fate of the inquiry into of voluntary assisted dying inundated with surveys before among 93 MPs willing to palliative care conducted by the elections. -

View the Queensland Greens Response

.A FUTURE FOR ALL OF US. Stacey Rawlings Queensland Manager Engineers Australia by email only to [email protected] Thursday 16 November 2017 Dear Stacey, ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA POSITION STATEMENT QUEENSLAND GREENS RESPONSE Thank you for the opportunity to respond to your position statement. The Queensland Greens is the party for our planet and for creating and building our future. This state election campaign has proven once again that the major parties are incapable of articulating a real positive vision for the future of Queensland - and once again, it has been up to the Greens to show them how it’s done. Engineering as a profession is not only central to so many of the drivers of Queensland’s economy, we believe engineers are key to solving our problems today, to build a better tomorrow. Just this campaign, we’ve announced a number of massive, fully-costed packages that would be of interest to your members: • A Home for All - The Queensland Greens’ plan to build a million affordable homes over 30 years, creating 160,000 jobs in the first ten years. You can find out more at greens.org.au/qld/homeforall. • Power for People - The Queensland Greens’ plan to invest $15 billion over 5 years to build Queensland’s secure and publicly-owned sustainable energy future, creating 5,500 jobs every year. You can find out more at greens.org.au/qld/powerpeople. • A Queensland Public Infrastructure Bank - The Queensland Greens’ plan to create a $10 billion infrastructure bank to build publicly-owned infrastructure all across Queensland, creating a state- wide jobs and investment boom, and focusing on upgrading schools and hospitals in high-need areas and supporting regional communities diversifying out of extractive industries or hit hard by climate change. -

Members of the Legislative Assembly 57Th Parliament

Les Walker Steven Miles Deb Frecklington Robert Skelton James Martin John-Paul Langbroek Mark Boothman Aaron Harper Mundingburra Murrumba Nanango Nicklin Stretton Surfers Paradise Theodore Thuringowa ALP ALP LNP ALP ALP LNP LNP ALP Members of the Legislative Assembly 57th Parliament Dan Purdie Sandy Bolton Leanne Linard Mark Robinson Peter Russo Trevor Watts David Janetzki Scott Stewart Ninderry Noosa Nudgee Oodgeroo Toohey Toowoomba Toowoomba Townsville LNP IND ALP LNP ALP North LNP South LNP ALP Nikki Boyd Ali King Yvette D’Ath Kim Richards Robbie Katter Ann Leahy Shannon Fentiman Amanda Camm Pine Rivers Pumicestone Redcliffe Redlands Traeger Warrego Waterford Whitsunday ALP ALP ALP ALP KAP LNP ALP LNP ALP Australian Labor Party 51 LNP Liberal National Party 34 KAP Katter’s Australian Party 3 Barry O’Rourke Stirling Hinchliffe Jon Krause Amy MacMahon Cameron Dick Rockhampton Sandgate Scenic Rim South Brisbane Woodridge ALP ALP LNP GRN ALP GRN Queensland Greens 2 PHON Pauline Hanson’s One Nation 1 IND Independent 1 92 Parliament House George Street Brisbane Qld 4000 James Lister Rob Molhoek Mick De Brenni Jimmy Sullivan ph: (07) 3553 6000 www.parliament.qld.gov.au Southern Downs Southport Springwood Stafford updated August 2021 LNP LNP ALP ALP Leeanne Enoch Bart Mellish Chris Whiting Craig Crawford Cynthia Lui Michael Crandon Jonty Bush Laura Gerber Brittany Lauga Shane King Jim McDonald Linus Power Algester Aspley Bancroft Barron River Cook Coomera Cooper Currumbin Keppel Kurwongbah Lockyer Logan ALP ALP ALP ALP ALP LNP ALP LNP ALP -

14 October 2020 Mr Paul Wright National Director

14 October 2020 Mr Paul Wright National Director, Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation Via email: [email protected] 2020 Queensland state election - policy platform Dear Paul, Thank you for your email of 1 October 2020, enquiring about the Queensland Greens’ policy platform ahead of the 2020 Queensland state election. It’s clear that Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (ANTaR) is setting a vital agenda for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs policy in Australia. For your reference, the Queensland Greens’ election platform for the 2020 State Election is online at: https://greens.org.au/qld/plan. Our long-standing broader policy platform is here: https://greens.org.au/qld/policies. As I’m sure you would understand, if the Greens find ourselves in a balance-of-power scenario there is an enormous list of competing priorities, and the final decision on any negotiated outcome rests with the party as a whole. However, many of the priorities you have identified align with our agenda. Our fully costed plan sets out our agenda to create thousands of good secure jobs and fully fund public health and education, funded by making big mining corporations, banks and developers pay their fair share in tax. As requested, I have responded to your priorities below. All statements are complementary to statements by the Greens’ spokespeople, including myself, and other policy documents that are on the public record. 1. Treaty The Greens firmly support a treaty process, to be led by the Indigenous community, and on this basis we are committed to taking the current Queensland government treaty-making process forward. -

Published on DES Disclosure Log RTI Act 2009

From: TRACEY Alena [[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, 11 January 2018 10:08 PM To: Angus Sutherland CC: Virginia Dale; CLEMENTS Caley Subject: RE: Meeting with Minister week beginning 15 Jan - New Acland and s.73 - Not Relevant Sorry Attendees with be Dean Ellwood, DDG ESR; Anne Lenz, ESR and Alena Tracey. A Alena Tracey Senior Director Office of the Director-General Department of Environment and Science ---------------------------------------------------------------- E [email protected] Log M Schedule 4 - CTPI Level 32, 1 William Street, Brisbane Qld 4000 From: TRACEY Alena Sent: Thursday, 11 January 2018 10:08 PM To: '[email protected]' Cc: '[email protected]'; CLEMENTS Caley Subject: Meeting with Minister week beginning 15 Jan - New Acland s.73 - Not Relevant Hi Angus Disclosure Today, the Director-General was briefed on the upcoming New Acland mine expansion application decision timeframe (14 February) and s.73 - Not Relevant Given the time sensitivity of both these, Jamie suggested that the Minister be briefed by the DES team next week. 2009 Can you please organise a briefing of the Minister for next week? I would suggest an hour given the issues with both these matters. I am not sure of the urgency of the Mine RehabilitationDES and Climate Change briefings that are currently scheduled so, if stuck, it may be possible to use one of those slots. Act Thanks Alena on Alena Tracey Senior Director RTI Office of the Director-General Department of Environment and Science ---------------------------------------------------------------- E [email protected] M Schedule 4 - CTPI Level 32, 1 William Street, Brisbane Qld 4000 ------------------------------ The informationPublished in this email together with any attachments is intended only for the person or entity to which it is addressed and may contain confidential and/or privileged material.