An Evaluation of Maternity Care Provided in Three Sure Start Local Programmes in Islington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote for Oral Presentations and Posters at 1

Vote for oral presentations and posters at www.sli.do/HSRUK19 1 Welcome 3 Information 4 Programme 6 Session Summaries 10 Rapid Fire Session Listings 12 Posters 15 Speaker Biographies 20 Exhibitors 24 HSR UK Membership 25 2 Vote for oral presentations and posters at www.sli.do/HSRUK19 WELCOME Welcome to the Health Services Research UK annual conference for 2019 We are delighted to welcome you to the largest and most diverse annual conference that HSR UK has ever organised. Our programme of five plenary sessions, and the dozens of workshops, invited sessions, oral paper presentations and poster presentations over two days are a testament to the growth in health services research over recent years in the United Kingdom, and the existence of a thriving and creative research community. With around 350 people from universities, thinktanks, research funders, NHS organisations, patient and public involvement groups and other stakeholders gathered in Manchester it presents an unparalleled opportunity to see the state of the science in HSR, meet and network with colleague and collaborators. There are awards for the best oral presentations and posters at the conference, and this year we want everyone to contribute by voting for oral presentations and posters that they like – go to www.sli.do/HSRUK19 and enter the 3 digit code beside the presentation or poster in this programme. You can vote for as many different presentations/posters as you like but can only vote once for each one! The awards will be announced at the closing plenary. These are uncertain and difficult times for the NHS in all four countries of the UK, but perhaps particularly in England where the difficult legacy of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 is slowly being unpicked. -

Kettering General Hospital Nhs Foundation Trust in Association with Eastman Dental Hospital and Institute University College London Hospitals Nhs Foundation Trust

KETTERING GENERAL HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST IN ASSOCIATION WITH EASTMAN DENTAL HOSPITAL AND INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST SPECIALIST REGISTRAR POST IN ORTHODONTICS JOB DESCRIPTION 2021 APPOINTMENT This job description covers a full-time non-resident Specialist Registrar post in Orthodontics. The duties of this post will be split between Kettering General Hospital and the Eastman Dental Institute, with three days spent in Kettering and two days in the Eastman Dental Institute. This post will be based administratively at the Trent Deanery, Sheffield. The Postgraduate Dental Dean has approved this post for training on advice from the SAC in Orthodontics. The posts have the requisite educational and staffing approval for specialist training leading to a CCST and Specialist Registration with the General Dental Council. The successful candidate will be required to register on the joint training programme leading to the M.Orth.RCS and the MClin.Dent. in Orthodontics at the University of London (unless they already hold equivalent qualifications). This appointment is for one year in the first instance, renewable for a further two years subject to annual review of satisfactory work and progress. Applicants considering applying for this post on a Less Than full Time (flexible training) basis should initially contact the Postgraduate Dental Dean’s office in Sheffield for a confidential discussion. QUALIFICATIONS/EXPERIENCE REQUIRED Applicants for specialist training must be registered with the GDC, fit to practice and able to demonstrate that they have the required broad-based training, experience and knowledge to enter the training programme. Applicants for orthodontics will be expected to have had a broad based training including a period in secondary care, ideally in Oral and Maxillofacial surgery and paediatric dentistry and to have completed a 2 year period of General Professional Training. -

Charitable Funds Annual Report 2004/2005

Charitable Funds Annual Report 2004/2005 Registered charity number 1056452 The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust Charitable Fund Trustees Narendra Makanji Trust Chairman Andrew Riley Chief Executive (until September 2004) David Sloman Chief Executive (from November 2004) Susan Sorensen Director of Finance and Strategic Development Deborah Wheeler Director of Nursing and Clinical Development Margaret Boltwood Director of Human Resources and Corporate Affairs Tara Donnelly Director of Operations Michael Lloyd Director of Site Commissioning Norman Parker Medical Director (until October 2004) Celia Ingham Clark Medical Director (from November 2004) Maria Duggan Non Executive Director Peter Farmer Non Executive Director Pat Gordon Non Executive Director Doreen Henry Non Executive Director Anne Johnson Non Executive Director Michael Worton Non Executive Director (until May 2004) Charity Funds Administration Elizabeth Hall Charitable Funds Accountant Keith Wenden Head of Fundraising Anna Turner Fundraising and Communications Secretary Description of Trusts Although all funds are held within an Umbrella Charity, a small number of funds have their own governing instruments and are registered as specific purpose funds within the overall charitable fund. Charity Objects 1. Umbrella Charity For any charitable purpose or purposes relating to the National Health Service wholly or mainly for the services provided by the Whittington Hospital NHS Trust 2. The Royal Northern Scheme General Purpose Fund As for the Umbrella Charity GHE Bequest The primary objects being to provide facilities and amenities to patients to relieve suffering and anxiety and to aid recovery. The secondary objects refer to the maintenance and improvement of facilities for fee-paying patients and to subsidise their costs in cases of need as determined by the Trustees Nursing Staff Fund To provide amenities for nursing staff at the Whittington Hospital 3. -

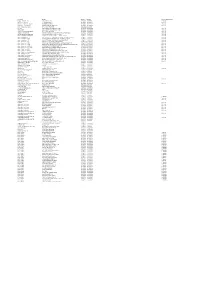

201819 Master Contract List FINAL 11072018 to Be Added to Website.Xlsx

Description Provider Start Date End Date Contract Notice Period Diagnostic Services ‐ ISTC InHealth Netcare Ltd 01/07/2014 30/06/2018 12 Months Specialist Pallative Care ST JOSEPHS HOSPICE 01/04/2016 01/03/2019 1 Month Pallative care (Childrens hospice) RICHARD HOUSE TRUST 01/04/2016 31/03/2019 7 Months HIV Services ‐ non consortia MILDMAY MISSION HOSPITAL UK 01/04/2016 31/03/2019 3 Months Newham Urgent Care Centre BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 20/11/2013 31/05/2018 ELFT CHS EAST LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 3 Months Mental Health EAST LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 7 Months Acute ‐ In Area SLA ‐ Barts Health BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ In Area SLA ‐ HUH HOMERTON UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Ambulance Service ‐ Urgent Care LONDON AMBULANCE SERVICE NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 3 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ Moorfields MOORFIELDS EYE HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ UCLH UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ BHRUT BARKING HAVERING AND REDBRIDGE HOSPITALS NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ GST GUYS & ST THOMAS HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ ICH IMPERIAL COLLEGE HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ Out of Area ‐ C&W CHELSEA AND WESTMINSTER HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 01/04/2017 31/03/2019 6 Months Acute ‐ -

2018/19 Trust Performance Uptake for Hcws Influenza Vaccinations by STP

2018/19 Trust Performance Uptake for HCWs Influenza Vaccinations by STP Trust Type North Central London STP 18/19 % Uptake Mental Health BARNET, ENFIELD AND HARINGEY MENTAL HEALTH NHS TRUST 58.8 Community CAMDEN AND ISLINGTON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 42.9 Specialist GREAT ORMOND STREET HOSPITAL FOR CHILDREN NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 60.0 Specialist MOORFIELDS EYE HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 77.6 Acute NORTH MIDDLESEX UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL NHS TRUST 70.4 Acute ROYAL FREE LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 49.4 Specialist ROYAL NATIONAL ORTHOPAEDIC HOSPITAL NHS TRUST 76.6 Acute THE WHITTINGTON HOSPITAL NHS TRUST 83.4 Acute UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 50.8 North East London STP Acute BARKING, HAVERING AND REDBRIDGE UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS NHS TRUST 60.7 Acute BARTS HEALTH NHS TRUST 63.1 Mental Health EAST LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 60.8 Acute HOMERTON UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 70.2 Mental Health NORTH EAST LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 59.6 North West London STP Mental Health CENTRAL AND NORTH WEST LONDON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 76.0 Community CENTRAL LONDON COMMUNITY HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 40.4 Acute CHELSEA AND WESTMINSTER HOSPITAL NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 81.1 Acute IMPERIAL COLLEGE HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 60.2 Acute LONDON NORTH WEST HEALTHCARE NHS TRUST 55.6 Specialist ROYAL BROMPTON & HAREFIELD NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 60.9 Community TAVISTOCK AND PORTMAN NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 61.5 Acute THE HILLINGDON HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST 75.2 Mental Health WEST LONDON MENTAL HEALTH NHS TRUST 47.5 South East London STP Acute GUY'S -

Improving Planned Orthopaedic Surgery for Adults in North Central

Improving planned orthopaedic surgery for adults in north central London 13 January to 6 April 2020 We are proposing changes to planned surgery for bones, joints and muscles (planned orthopaedic surgery) for adults. This includes hip and knee replacements; and other surgery of hips, knees, shoulders, elbows, feet, ankles and hands. Any changes could affect residents of Barnet, Camden, Enfield, Haringey and Islington and neighbouring boroughs. We need your comments and advice. Closing date for feedback 6 April 2020 A consultation document published by North London Partners in health and care on behalf of Barnet, Camden, Enfield, Haringey and Islington clinical commissioning groups. Introduction Helen Pettersen Prof Fares Haddad North London Partners in Clinical Lead for the review, Clinical Director of the Health and Care Convenor and Institute of Sport and Exercise Health and a Consultant accountable officer of NCL’s Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgeon at University College five CCGs London Hospitals North London Partners in health and care was established to tackle As a surgeon, who provides this kind of care every day, I know the Hospitals across north central London have some of the big health and care challenges we face in the coming difference it makes to patients. Damage to bones, joints and muscles years. We are a partnership of health and care organisations who are can be debilitating for people of all ages - whether it is a result of proposed a new way to organise orthopaedic working together to find solutions to address these challenges. Our ageing or trauma - but with the right care at the right time, the review of orthopaedic services is a good example of this. -

Adjunctive Colposcopy Technologies for Assessing Suspected Cervical Abnormalities : Systematic Reviews and Economic Evaluation

This is a repository copy of Adjunctive colposcopy technologies for assessing suspected cervical abnormalities : systematic reviews and economic evaluation. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/136987/ Version: Published Version Article: Peron, Mathilde, Llewellyn, Alexis orcid.org/0000-0003-4569-5136, Moe-Byrne, Thirimon orcid.org/0000-0002-2827-9715 et al. (5 more authors) (2018) Adjunctive colposcopy technologies for assessing suspected cervical abnormalities : systematic reviews and economic evaluation. Health technology assessment. pp. 1-260. ISSN 2046-4924 https://doi.org/10.3310/hta22540 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT VOLUME 22 ISSUE 54 SEPTEMBER 2018 ISSN 1366-5278 Adjunctive colposcopy technologies for assessing suspected cervical abnormalities: systematic reviews and economic -

Hospital Directory

HOSPITAL DIRECTORY ‘Health is not simply the absence of sickness.’ Hannah Green WHITTINGTON HOSPITAL REVIEW 2005 www.whittington.nhs.uk HOSPITAL DIRECTORY INTRODUCTION This information pack has been put together to inform GPs and other health professionals about the wide range of services the Whittington Hospital provides and how they can be accessed. If you want further details on each department and consultants’ sub-specialties please go to our website www.whittington.nhs.uk and look under clinical services. I hope you find this book useful. I would be interested to have your views. Mrs Celia Ingham Clark Medical Director [email protected] 63 HOSPITAL DIRECTORY HOSPITAL DIRECTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information Surgery Outpatient referral procedures . .111 Anaesthetic services . .67 Inpatient admissions . .98 Cancer care . .69 On call arrangements . .107 Day surgery . .80 Security . .126 ENT and Audiology . .86 Parking and transport . .114 General surgery . .92 Useful telephone numbers . .132 Ophthalmology . .108 Orthopaedics . .109 Diagnostics and Therapies Theatres . .127 Clinical Nutrition . .78 Urology . .128 Imaging . .96 Occupational therapy . .105 Women and Children’s Health Service Pathology . .115 Maternity . .100 Physiotherapy . .118 Children’s Health . .75 Podiatry . .120 Women’s health . .130 Speech and language therapy . .125 Private Patients . .121 Medical Services Acute medicine . .66 Miscellaneous Cardiology . .72 PALS Team (including complaints) . .117 Care of older people . .74 Parking and -

More Than Just a Driver

More than just a driver 44 ........... Other road users 46 ........... Using the public address (PA) system 49 ...........Pre-recorded announcements 43 More than just a driver More than just a driver Being a professional bus driver requires more than just giving your passengers a safe, smooth ride. This section gives you guidance on other aspects of your job which will help you keep up your status as a professional. More than just a driver Other road users 44 Other road users There are many more cyclists using London’s roads and you should take special care to ensure you are aware of cyclists at all times. Look out for Barclays Cycle Superhighways across the Capital, and Barclays Cycle Hire users in central and eastern areas. 1. Give all cyclists space as you overtake (about half the width of your bus, or 1.2m) and do not cut in on cyclists as you approach bus stops. 45 More than just a driver Other road users 2. Do not stop in the Advanced Stop Box. It must be left clear for cyclists. 3. Remember to watch out for motorcyclists, who can now use certain bus lanes. 4. Watch out for pedestrians and keep your speed low. Use dipped headlights, especially in contra-flow bus lanes and central areas, such as Oxford Street or Piccadilly. Your company may ask you to use dipped headlights at all times. 5. At road junctions, be aware of other large vehicles such as lorries. Like buses, they need a wide area to turn. 6. Remember, taxis can use bus lanes so be prepared to stop if they are picking up or setting down passengers. -

In Your Area: London Region

In your area: London region Supporting you locally In your area – London region 1 Our mission: We look after doctors so they can look after you. Our values: Expert Challenging We are an indispensable source of credible We are unafraid to challenge effectively on behalf information, guidance and support throughout of all doctors. doctors’ professional lives. Leading Committed We are an influential leader in supporting the We are committed to all doctors and place them at profession and improving the health of our nation. the heart of every decision we make. Reliable We are doctors’ first port of call because we are trusted and dependable. 2 British Medical Association Code of conduct Our behaviours We have taken the BMA’s values – expert, leading, Members are required to familiarise themselves with challenging, committed and reliable – and with your the BMA’s constitution as set out in the memorandum help, turned them into behaviours to provide clarity and articles of association and bye-laws of the on what we expect from each other as we go about our Association. The code of conduct provides guidance work and provide a consistent approach for discussing on expected behaviour and sets out the standards of behaviour. They describe what we expect of each other, conduct that support BMA’s values in the work it does. and what we don’t, as well as what is considered above www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/committees/ and beyond. Our behaviours form part of our culture committee-policies/bma-code-of-conduct) change to become a better BMA. -

The Changing Role of the Hospital in European Health Systems

The Changing Role of the Hospital in European Health Systems Hospitals today face a huge number of challenges, including new patterns of disease, rapidly evolving medical technologies, ageing populations and continuing budget con- straints. This book is written by clinicians for clinicians and hospital managers, as well as those who design and operate hospitals. It sets out why hospitals need to change as the patients they treat and the technology to treat them change. In a series of chapters by leading authorities in their field, it challenges existing models, reviews best practice from many countries and presents clear policy recommendations for policy-makers and hospital administrators. It covers the main patient groups and conditions as well as those departments that make modern effective care possible, in imaging and laboratory medicine. Each chapter looks at patient pathways, aspects of workforce, required levels of specialization and technology, and the opportunities and challenges for optimizing the delivery of services in the hospital of the future. Martin McKee cbe is Professor of European Public Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Research Director of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, and Past President of the European Public Health Association. His contributions have been recognized by election to the UK Academy of Medical Sciences, Academia Europeae, and the US National Academy of Medicine, and by six honorary doctorates. He was awarded the 2003 Andrija Stampar medal, the 2014 Alwyn Smith Prize, and the 2015 Donabedian International Award. sherry MerKur is a Research Fellow and Health Policy Analyst at the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, based at the London School of Economics and Political Science. -

Response to Regulation 28 Coroner's Report To

RESPONSE TO REGULATION 28 CORONER’S REPORT TO PREVENT FUTURE DEATHS 1 THIS RESPONSE IS MADE ON BEHALF OF University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust 2 REGULATION 28 REPORT THIS REPORT IS BEING SENT TO: Marcel Levi, Chief Executive, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 235 Euston Road, London. NW1 2BU. (UCLH) 3 CORONER I am R Brittain, assistant coroner, for Inner North London 4 CORONER’S LEGAL POWERS I make this report under paragraph 7, Schedule 5, of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 and regulations 28 and 29 of the Coroners (Investigations) Regulations 2013. 5 INVESTIGATION AND INQUEST Michael Brennan died on 24 October 2016, aged 80. The inquest into his death concluded on 17 March 2017. Mr Brennan died from the consequences of small cell carcinoma. The conclusion of the inquest was narrative. 6 CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE DEATH Mr Brennan began coughing up blood in early 2016. He had a background history of cigarette smoking and had been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. His symptoms were investigated by chest x-ray and subsequently by CT scan. A repeat scan demonstrated a persistent area of concern. Before further investigations could be undertaken he was admitted to Whittington Hospital and treated for a serious infection. In order to investigate the underlying cause of his symptoms a bronchoscopy was performed, after his condition had somewhat improved. During this procedure a mass was noted which was felt likely to be a lung cancer. This lesion started to bleed and was treated with the available methods of cold saline and adrenaline washes.