The Meaning of the Global War on Terror in Post-9/11 U.S. Presidential Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Edition

2012 Edition Cleveland State Community College ENGLISH DEPARTMENT Editor: Julie Fulbright Assistant Editor: Heather Cline Liner Front cover photography by: Amanda Guffey Graphic Design and Production: CSCC Marketing Department Printer: Dockins Graphics, Cleveland, Tenn. Copyright: 2012 Cleveland State Community College www.clevelandstatecc.edu All Rights Reserved Funding for this publication provided under Title I of the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006. CSCC HUM/12095/04092012 - Cleveland State Community College is an AA/ EEO employer and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability or age in its program and activities. The following department has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies: Human Resources P.O. Box 3570 Cleveland, TN 37320-3570 [email protected] Table of Contents Written By Title Photo/Drawing By: Page Frankie Conar After the Storm Julie Fulbright 5 Brittney Glover Weep for Me James Loyless 6 Leaves of the Sea Amanda Guffey 7 Stormy Fisher Mother 8 Savannah Tioaquen I Am the Wind Brandon Perry 9 Tracey Thompson Rose Amanda Guffey 10 Mirror Mirror Megan Payne 11 Tonya Arsenault Siblings Marchelle Wear 12-13 We Can’t Go Back in Time Kimberley Stewart 14-15 Angel Jadoobirsingh Spying Angel Jadoobirsingh 16 My Pay Angel Crawford 17 Cody Thrift Through Solemn Eyes Misti Stoika 18 I Had a Dream I Died Alonzo Bell 19-20 The Hero Tonya Arsenault 21-22 Nicholas Johnson Such Is Life Angel Jadoobirsingh 23 Turn the Lights Out 24 The Window by the Tree Marchelle Wear 25 Chet Guthrie Christmas on the Battlefield Amanda Guffey 26-29 Sweet Kalan Tonya Arsenault 30-34 The 23rd Psalm Marchelle Wear 35-37 Letters through the Fence Marchelle Wear 38-42 Grandfather’s Axe Marchelle Wear 43-44 Her Beauty Daniel Stokes 45 In the Eyes of a Dreamer Megan Payne 46 Rise o’ Rise Dear Wall Street 47 The Old Man Michael Espinoza 48 A Night of Passion Shanna Calfee 49-50 Table of Contents - Cont’d. -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 2017 This List Is Compiled Based on Over 2 Million Song Requests Made Using the DJ Event Planner Song Request System

The UK Top 200 Most Requested Songs In 2017 This list is compiled based on over 2 million song requests made using the DJ Event Planner song request system. Rank Song Song Title 1 Mark Ronson feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Killers Mr. Brightside 3 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 4 Pharrell Williams Happy 5 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 6 Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire 7 Bryan Adams Summer Of '69 8 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 9 ABBA Dancing Queen 10 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 11 Bruno Mars Marry You 12 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 13 Dexys Midnight Runners Come On Eileen 14 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 15 Queen Don't Stop Me Now 16 Rihanna feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 17 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 18 Ed Sheeran Shape Of You 19 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 20 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 21 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 22 Beyonce feat. Jay-Z Crazy In Love 23 Oasis Wonderwall 24 Wham! Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go 25 B-52's Love Shack 26 John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John Grease Megamix 27 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 28 Maroon 5 Moves Like Jagger 29 Los Del Rio Macarena 30 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 31 Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O' Mine 32 Toploader Dancing In The Moonlight 33 Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor 34 Mark Ronson feat. Amy Winehouse Valerie 35 House Of Pain Jump Around 36 Stevie Wonder Superstition 37 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

The Cathedral of the Diocese of Manchester the Most Reverend

Saint Joseph Cathedral The Cathedral of the Diocese of Manchester The Most Reverend Peter A. Libasci Tenth Bishop of Manchester Clergy August 22, 2021 Very Reverend Jason Y. Jalbert Rector and Pastor TwentyFirst Sunday in Ordinary Time Reverend Eric T. Delisle Pastor Saint Hedwig Weekend Mass: Reverend Deacon Karl T. Cooper Saturday 4:00 PM Permanent Deacon Sunday 8:30 AM, 10:30 AM, Pastoral and Office Staff 6:00 PM Kelly Bender Director of Faith Formation Weekday Mass: Eric J. Bermani MondayFriday (Chapel) 7:00 AM Director of Music First Friday (Chapel) 12:10 PM Karol Carroll Bookkeeper Saturday (Cathedral) 8:00 AM Stacey Donovan Holy Days as announced Administrative Assistant Judy LabbeHuard Confessions: Director of Communications & MondayFriday (Chapel) Parish Support 7:308:00 AM Saturday (Cathedral) In Residence 7:308:00 AMand 2:303:30 PM Most Reverend Francis J. Christian Auxiliary Bishop Emeritus 145 Lowell Street Monsignor C. Peter Dumont Manchester, New Hampshire 03104 Reverend Elson Kattookaran M.S. www.stjosephcathedralnh.org Chaplain Catholic Medical Center Telephone: 6036226404 Reverend Jeffrey Statz Pastor St. Francis of Assisi Rectory Office Hours: MondayThursday 9:00 a.m.2:00 p.m. Follow us on Facebook: Cathedral of Saint Joseph, Manchester, New Hampshire SǂNJǏǕ JǐǔdžǑlj CǂǕljdžDžǓǂǍ, MǂǏDŽljdžǔǕdžǓ, NH From the Desk of Father Jason Dear Friends, Prayer to Saint Monica This week the Church celebrates the feast days of a mother Under the weight of my heartful burden, I turn to you, dear and her son. On Friday the 27th we honor St. Monica and on Saint Monica and request your assistance and intercession. -

Wycliffe Gordon at GRU

World-renownedtrombonist Practiceby Jim Garvey makes Wycliffehas reached Gordon the pinnacle ofand music now success he is Perfect with the sharing his expertise music department at GRU. HOW DO YOU GET TO GRU’S MAXWELL THEATRE? PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE. At least that’s how Wycliffe Gordon, the best jazz trombonist in the world, got there. After years of teaching at Juilliard and the Manhattan School of Music, touring the world with Wynton Marsalis and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, performing with symphony orchestras, recording, com- posing, arranging, giving workshops, lectures and master classes, Gordon was finally offered the job he’s been preparing for all these years: artist-in-residence in GRU’s Department of Music. “I’ve come full circle, teaching at a university in my own town after teaching all over the world,” Gordon says. “I’m from here. My high school, Butler High School, is here. My mom lives here. Coming to GRU is Jazz trombonist and composer Wycliffe Gordon performs on stage at like icing on the cake.” u Davidson Fine Arts School in 2008. 32 • Augusta April 2015 April 2015 Augusta • 33 “...a full, powerful tone, slurring then slippingsliding and growling BUT TRADING IN NEW YORK CITY FOR HEPHZIBAH? His fame is never on display. With his round, boyish face and twinkling eyes, “I had a place in New York for 15 “During his solo, Gordon locked in Currier, an opera singer who has sung he’s more playful imp than musical phenom. Still phenom is what he is. years. I’ve had enough pretty much. -

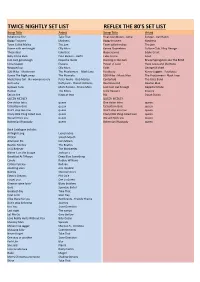

Twice Nightly Set List Reflex the 80'S Set List

TWICE NIGHTLY SET LIST REFLEX THE 80'S SET LIST Song Title Artist Song Title Artist Relight my Fire Take That Final countdown - Jump Europe - Van Halen Baggy Trousers Madness Baggy trousers Madness Town Called Malice The jam Town called malice The jam Dance with me tonight Olly Murs Karma Chameleon Culture Club / Boy George These days take that Hope Joanna Eddie Grant Baby Come Back Pato Banton - UB40 Take on me A-HA Just cant get enough Depeche mode Dancing in the dark Bruice Springstein aka The BOSS Little respect Erasure Power of Love Huey Lewis and the News Wrapped up Olly Murs Faith George Michael 500 Miles - Music man The Proclaimers - Black Lace Footloose Kenny Loggins - Footloose Dance The Night away The Mavricks 500 Miles - Music Man The Proclaimers - Black Lace Mysterious Girl - No woman no cry Peter Andre - Bob Marley Centerfold The Giles Band Get Lucky Daft punk - Pharell Williams Real Gone Kid Deacon Blue Uptown Funk Mark Ronson - Bruno Mars Just Cant Get Enough Depeche Mode Human The Killers Little Respect Erasure Sex on fire Kings of leon Rio Duran Duran QUEEN MEDLEY QUEEN MEDLEY One vision Intro queen One vision Intro queen fat bottom Girls queen fat bottom Girls queen Don’t stop me now queen Don’t stop me now queen Crazy little thing called love queen Crazy little thing called love queen We will Rock you queen We will Rock you queen Bohemian Rhapsody queen Bohemian Rhapsody queen Back Catalogue include; All Night Long Lionel richie All Star Smash Mouth American Pie Don Mclain Beatles Medley The Beatles Im A Believer The -

Terrorism - the Efinitd Ional Problem Alex Schmid

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 36 | Issue 2 2004 Terrorism - The efinitD ional Problem Alex Schmid Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Alex Schmid, Terrorism - The Definitional Problem, 36 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 375 (2004) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol36/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. TERRORISM - THE DEFINITIONAL PROBLEM* Alex Schmidt "Increasingly, questions are being raised about the problem of the definition of a terrorist. Let us be wise and focused about this: terrorism is terrorism.. What looks, smells and kills like terrorism is terrorism." - Sir Jeremy Greenstock, British Ambassador to the UnitedNations, in post September 11, 2001 speech' "It is not enough to declare war on what one deems terrorism without giving a precise and exact definition." - PresidentEmile Lahoud,Lebanon (2004)2 "An objective definition of terrorism is not only possible; it is also indispensable to any serious attempt to combat terrorism." - Boaz Ganor,Director of the InternationalPolicy Institutefor Counter- Terrorism3 * Presented at the War Crimes Research Symposium: "Terrorism on Trial" at Case Western Reserve University School of Law, sponsored by the Frederick K. Cox International Law Center, on Friday, Oct. 8, 2004. t The views and opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not represent official positions of the United Nations which has not yet reached a consensus on the definition of terrorism. -

Entire Issue (PDF)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2011 No. 20 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Thursday, February 10, 2011, at 4 p.m. House of Representatives WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2011 The House met at 10 a.m. and was to our kids and our grandkids and sidies in the agriculture bill for five called to order by the Speaker pro tem- won’t be paid off over 30 years. Some of crops grown in eight States that are in pore (Mr. WEBSTER). this debt will weigh upon the country. surplus and paying people not to grow f But the question is, how do we get things. That’s off-limits. That’s man- there? The deficit this year will be $1.5 datory spending. That can’t be consid- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO trillion, an unimaginable amount of ered for cuts, paying people to not TEMPORE money, borrowed, a lot of it from grow things. We can’t do away with The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- China, and that is just virtually that. We’re going to borrow the money fore the House the following commu- unfathomable. so they can get paid to not grow nication from the Speaker: Now, they’re going to dink around es- things. sentially and pretend they’re doing WASHINGTON, DC, All right. Well, how about the oil February 9, 2011. -

What Is a Day You Will Never Forget?

Personal Narrative What Is A Day You Will Never Forget? Mrs. Allen’s 5th Graders October 2016 1 A Day I Will Never Forget By Karleigh Adair A day I will never forget is the day when we smushed sprinkles, marshmallows, and starbursts together. Then, we heated them up, and ate them. First, Mrs. Allen did it herself. The results looked like a bubbling, burnt rainbow. Then we tried it. It was really messy, but super fun! I got to share a plate with Sam and Anantha. When we heated them up, they were not burnt this time. We used our fingers to eat them, and they tasted sooo good! We ate them all up! Our fingers were really sticky, so we had to wash them, and that is a day I will never forget. 2 Sarah Alhashimi Mrs. Allen 11/16/2016 A Day I Will Never Forget I always watch my best friends doing the things I never thought I could do. One of them was trying to do cartwheels. I tried practicing at home. I searched up how to do cartwheels on the internet and i followed what they told me to do. I was scared, But i recorded myself trying to do my very rst cartwheel. I believed in myself, and I did it. I was jumping with happiness. I ran to my phone to see what i looked doing it. I watched myself doing a cartwheel, but I wasn’t too happy with way I did it. I noticed my legs were not straight and so were my arms. -

Never Forget, Never Again

“I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.” Jewish author and Holocaust survivor, Elie Wiesel, from his Nobel Prize acceptance speech From the Rabbi Each year Jews around the world observe Yom HaShoah — Holocaust Remembrance Day — commemorating a horrific chapter not only in the history of the Jewish people, but also in the history of the world. Motivated by a fanatical hatred of Jews and a desire to rid society of “undesirable” elements, the Nazi regime that ruled Germany during the mid-20th century engaged in a systematic and brutal campaign to destroy the Jewish people. Harvesting the fruits of seeds sown through centuries of anti-Semitism, they nearly succeeded, murdering six million Jews, or about one third of the world’s Jewish population at the time. The full name of Holocaust Remembrance Day in Hebrew is actually “Yom HaShoah Ve-Hagevurah,” meaning “Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day.” This reminds us that even though many ignored evidence of Nazi crimes, there were those who went to great lengths to save Jews. Many of these heroes are remembered today as “righteous gentiles.” In Holland, Corrie ten Boom sheltered those fleeing Nazi oppression. In France, Pastor André Trocmé helped to make an entire town, Le Chambon, a safe haven for persecuted Jews. Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish Chris- tian, rescued thousands of Jews from the Nazi death machine. And there were, of course, many more who are less well-known, but no less deserving of our gratitude. -

Constitution Betrayed: Free Expression, the Cold War, and the End of American Democracy

- 1 - Constitution Betrayed: Free Expression, the Cold War, and the End of American Democracy Stephen M. Feldman, Housel/Arnold Distinguished Professor of Law and Adjunct Professor of Political Science, University of Wyoming I. Republican Democracy and Free Expression A. An Emphasis on Balance B. Changing Conceptions of Virtue and the Common Good: Corporations and Laissez Faire II. Pluralist Democracy Saves the United States and Invigorates Free Expression A. American Democracy Transforms: Reconciling the Public and Private B. Pluralist Democratic Theory: Free Expression Becomes a Constitutional Lodestar III. Pluralist Democracy Evolves: Free Expression, Judicial Conservatism, and the Cold War A. The Early-Cold War, Free Expression, and Moral Clarity B. The Flip Side of the Cold War: Liberty and Equality in an Emerging Consumers’ Democracy 1. Civil Rights and Democracy 2. Capitalism and Democracy IV. Democracy, Inc., and the End of the Cold War A. The Rise of Democracy, Inc.: An Attack on Government B. The Roberts Court in Democracy, Inc. V. Constitution Betrayed VI. Conclusion: Should We Praise or Blame the Framers? Constitution Betrayed: Free Expression, the Cold War, and the End of American Democracy This is a story of the Cold War and the betrayal of the American democratic-capitalist system.1 But the perpetrators of this iniquity are not Communists. Rather, they are the conservative justices of the Roberts Court. Their names are John Roberts, Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Anthony Kennedy. ______________________________ 1Many sources focus on the Cold War. Some helpful ones include the following: H.W. Brands, The Devil We Knew: Americans and the Cold War (1993); Greg Castillo, Cold War on the Home Front (2010); Richard B. -

Music Senior Spotlight 2021- Week of March

Emma Weeber Strings-Violin What is your favorite memory as a member of the MHS Music Department? The concerts were definitely my favorite part. During quarantine, I miss the sense of accomplishment and the excitement that surrounded each concert. I also loved having A period rehearsal because it was the best way to start each morning. I am so grateful that I got to be part of such an amazing ensemble for the past two years. What are your future plans? I plan on majoring in Math and English Education with a minor in Animal Science. I also plan to continue practicing in college! :) Ensembles: String Orchestra and Chamber What has music meant to you? Ensemble Music has been an outlet for me since I was little. I have always found myself returning to What are you listening to now? I mostly the violin after taking time off. Playing the listen to classical, Indie, and artists from the violin and listening to music during quarantine has helped me more than I could have ever early 2000s like Cold Play, Bon Iver, and The imagined. When I started playing, I never Lumineers imagined that I would fall in love with it as much as I have. I cannot wait to keep improving and discovering new playing styles! Aislinn Mershon Band- Oboe/Flute What is your favorite memory as a member of the MHS Music Department? I adored being a member of the Wind Ensemble during my sophomore year, where I had the opportunity to play several amazing pieces and work with and get to know a few great friends.