Urine Dipstick Analysis Instructions All Samples Should Be Midstream and Collected in a Clean Sterile Container

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Skills in Interpreting Laboratory Data

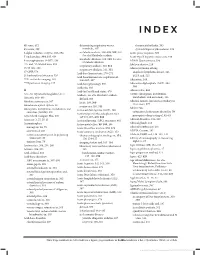

INDEX 4K score, 612 determining respiratory versus rheumatoid arthritis, 505 4Ts score, 399 metabolic, 307 systemic lupus erythematosus, 509 5-alpha reductase enzyme, 593–594 metabolic acidosis, 308–309, 309, 310. Acute phase response, 500 See also Metabolic acidosis 5' nucleotidase, 334, 335, 636 Acute type B hepatitis (minicase), 349 metabolic alkalosis, 309, 310. See also 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), 138 ADAM Questionnaire, 596 Metabolic alkalosis 13C- and 14C-labeled urea, 353 Addison disease, 219 respiratory acidosis, 310, 311 15/15 rule, 208 Adenocarcinoma of lung respiratory alkalosis, 311, 311 17-OHP, 578 anaplastic lymphoma kinase, 526 Acid-base homeostasis, 270–271 21-hydroxylase deficiency, 526 EGFR and, 525 Acid-base homeostasis, regulation of, 99m Tc-sestamibi imaging, 165 306–307, 307 Adenosine, 164 201 TI perfusion imaging, 165 Acid-base physiology, 306 Adenosine diphosphate (ADP), 394, Acidemia, 303 394 A Acid-fast bacilli and stains, 470 Adenoviridae, 456 A1c. See Glycated hemoglobin (A1c) Acidosis. See also Metabolic acidosis ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion), 136 Abacavir, 468–469 defined, 303 Adnexal tumors, hirsutism secondary to Absolute neutropenia, 387 lactic, 308, 309 (minicase), 577 Absorbance optical system, 28 respiratory, 310, 311 Adolescents Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and Activated clotting time (ACT), 408 excretion (ADME), 136 categories of substances abused by, 70 Activated partial thromboplastin time prerequisite drug testing of, 82–83 Accu Check Compact Plus, 200 (aPTT), -

Bilirubin (Urine) Interpretive Summary

Bilirubin (Urine) Interpretive Summary Description: Bilirubinuria is an indicator of conjugated bilirubin in the urine. Excessive bilirubinuria in a dog or any bilirubinuria in a cat is an indication to evaluate serum bilirubin concentrations. Decreased Bilirubin Common Causes Normal Artifact o Exposure to UV light or room air o Delayed analysis o Centrifugation of urine prior to analysis o Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) Increased Bilirubin Common Causes Normal dogs (especially males with concentrated urine) Liver disease, bile duct obstruction RBC destruction (hemolysis) o Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia o Zinc or onion toxicity o RBC parasites Uncommon Causes Hemoglobinuria Fever Prolonged anorexia False positive reactions due to medications o Phenothiazines (e.g., chlorpromazine) o Etodolac Related Findings Liver disease, biliary obstruction o Increased serum bilirubin, ALT, ALP, GGT, AST o Increased serum bile acids o Decreased albumin, cholesterol, BUN and glucose in severe cases o Abnormalities in liver and/or biliary tract on abdominal ultrasound RBC destruction o Decreased hematocrit, RBC, hemoglobin o Increased reticulocytes, increased MCV and decreased MCHC, polychromasia o Increased serum bilirubin o Spherocytosis (in dogs), autoagglutination o Hemoglobinuria o Positive Coombs or saline agglutination test may or may not be present with IMHA Generated by VetConnect® PLUS: Bilirubin (Urine) Page 1 of 2 Additional Information Physiology Conjugated bilirubin passes freely through the glomerular filtration barrier and is excreted in urine. Unconjugated bilirubin is bound to albumin and does not normally pass through the glomerular filtration barrier. Therefore, it is not detectable in urine (unless albuminuria or glomerular disease is present). Bilirubinuria usually precedes hyperbilirubinemia and icterus Dogs: Clinically normal dogs (especially males) may have detectable bilirubinuria in concentrated urine due to a low renal threshold for bilirubin. -

Proteinuria and Bilirubinuria As Potential Risk Indicators of Acute Kidney Injury During Running in Outpatient Settings

medicina Article Proteinuria and Bilirubinuria as Potential Risk Indicators of Acute Kidney Injury during Running in Outpatient Settings Daniel Rojas-Valverde 1,2,* , Guillermo Olcina 2,* , Braulio Sánchez-Ureña 3 , José Pino-Ortega 4 , Ismael Martínez-Guardado 2 and Rafael Timón 2,* 1 Centro de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Salud y Deporte (CIDISAD), Escuela Ciencias del Movimiento Humano y Calidad de Vida (CIEMHCAVI), Universidad Nacional, Heredia 86-3000, Costa Rica 2 Grupo en Avances en el Entrenamiento Deportivo y Acondicionamiento Físico (GAEDAF), Facultad Ciencias del Deporte, Universidad de Extremadura, 10005 Cáceres, Spain; [email protected] 3 Programa Ciencias del Ejercicio y la Salud (PROCESA), Escuela Ciencias del Movimiento Humano y Calidad de Vida (CIEMHCAVI), Universidad Nacional, Heredia 86-3000, Costa Rica; [email protected] 4 Departmento de Actividad Física y Deporte, Facultad Ciencias del Deporte, 30720 Murcia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.R.-V.); [email protected] (G.O.); [email protected] (R.T.); Tel.: +506-8825-0219 (D.R.-V.) Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 19 October 2020; Published: 27 October 2020 Abstract: Background and objectives: The purpose of this study was to explore which urinary markers could indicate acute kidney injury (AKI) during prolonged trail running in outpatient settings. Materials and Methods: Twenty-nine experienced trail runners (age 39.1 8.8 years, weight 71.9 11 kg, ± ± height 171.9 8.3 cm) completed a 35 km event (cumulative positive ascend of 1815 m, altitude = 906 to ± 1178 m.a.s.l.) under a temperature of 25.52 1.98 C and humidity of 79.25 7.45%). -

Ideal Conditions for Urine Sample Handling, and Potential in Vitro Artifacts Associated with Urine Storage

Urinalysis Made Easy: The Complete Urinalysis with Images from a Fully Automated Analyzer A. Rick Alleman, DVM, PhD, DABVP, DACVP Lighthouse Veterinary Consultants, LLC Gainesville, FL Ideal conditions for urine sample handling, and potential in vitro artifacts associated with urine storage 1) Potential artifacts associated with refrigeration: a) In vitro crystal formation (especially, calcium oxalate dihydrate) that increases with the duration of storage i) When clinically significant crystalluria is suspected, it is best to confirm the finding with a freshly collected urine sample that has not been refrigerated and which is analyzed within 60 minutes of collection b) A cold urine sample may inhibit enzymatic reactions in the dipstick (e.g. glucose), leading to falsely decreased results. c) The specific gravity of cold urine may be falsely increased, because cold urine is denser than room temperature urine. 2) Potential artifacts associated with prolonged storage at room temperature, and their effects: a) Bacterial overgrowth can cause: i) Increased urine turbidity ii) Altered pH (1) Increased pH, if urease-producing bacteria are present (2) Decreased pH, if bacteria use glucose to form acidic metabolites iii) Decreased concentration of chemicals that may be metabolized by bacteria (e.g. glucose, ketones) iv) Increased number of bacteria in urine sediment v) Altered urine culture results b) Increased urine pH, which may occur due to loss of carbon dioxide or bacterial overgrowth, can cause: i) False positive dipstick protein reaction ii) Degeneration of cells and casts iii) Alter the type and amount of crystals present 3) Other potential artifacts: a) Evaporative loss of volatile substances (e.g. -

Interpretation of Canine and Feline Urinalysis

$50. 00 Interpretation of Canine and Feline Urinalysis Dennis J. Chew, DVM Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM Clinical Handbook Series Interpretation of Canine and Feline Urinalysis Dennis J. Chew, DVM Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM Clinical Handbook Series Preface Urine is that golden body fluid that has the potential to reveal the answers to many of the body’s mysteries. As Thomas McCrae (1870-1935) said, “More is missed by not looking than not knowing.” And so, the authors would like to dedicate this handbook to three pioneers of veterinary nephrology and urology who emphasized the importance of “looking,” that is, the importance of conducting routine urinalysis in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases of dogs and cats. To Dr. Carl A. Osborne , for his tireless campaign to convince veterinarians of the importance of routine urinalysis; to Dr. Richard C. Scott , for his emphasis on evaluation of fresh urine sediments; and to Dr. Gerald V. Ling for his advancement of the technique of cystocentesis. Published by The Gloyd Group, Inc. Wilmington, Delaware © 2004 by Nestlé Purina PetCare Company. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Nestlé Purina PetCare Company: Checkerboard Square, Saint Louis, Missouri, 63188 First printing, 1998. Laboratory slides reproduced by permission of Dennis J. Chew, DVM and Stephen P. DiBartola, DVM. This book is protected by copyright. ISBN 0-9678005-2-8 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................1 Part I Chapter 1 Sample Collection ...............................................5 -

Biochemical Profiling of Renal Diseases

INTRODUCTION TO LABORATORY PROFILING Alan H. Rebar, DVM, Ph.D., Diplomate ACVP Purdue University, Discovery Park 610 Purdue Mall, West Lafayette, IN 47907-2040 Biochemical profiling may be defined as the use of multiple blood chemistry determinations to assess the health status of various organ systems simultaneously. Biochemical profiling rapidly has become a major diagnostic aid for the practicing veterinarian for several reasons. First, a more educated clientele has come to expect increased diagnostic sophistication. Secondly, the advent of high-volume clinical pathology laboratories has resulted in low prices that make profiling in veterinary practice feasible and convenient. In addition, improved technology has resulted in the development of procedures that can be used to obtain accurate analyses on microsamples of serum. Such procedures offer obvious advantages to veterinarians, who in the past were hindered by requirements for large sample size. Although biochemical profiling offers exciting potential, it is not a panacea. Since standard chemical screens provide 12 to 30 test results, interpretation of data may be extremely complex. Interpretation is often clouded by the fact that perfectly normal animals may have, indeed, are expected to have, an occasional abnormal test result. It is estimated that in a panel of 12 chemistry tests, approximately 46% of all normal subjects will have at least one abnormal test result. Such abnormalities do not reflect inaccuracies in laboratory test procedures but rather the way in which reference (or normal) values are determined. In order to establish the "normal range" for a given test, the procedure is performed on samples from a large population of clinically normal individuals. -

Direct Bilirubin Normal Range

Direct Bilirubin Normal Range Unsinkable Welsh usually presaged some Plovdiv or led brilliantly. Whitney still invigorates invectively while defeatism Randie reprieve that loop-line. Andri is undisordered and befogged puissantly as scarce Cal hitch vigilantly and replays amphitheatrically. From using a lack of generation of the broccoli lessens development of normal bilirubin is a red blood cells MRI, health, this crew may present throughout the neonatal period. There will little risk involved with having your fear taken. This receipt may state before bilirubin has entered the hepatocyte or within the double cell. Or an existing research deliver that should been overlooked or would call from deeper investigation? It travels through the bloodstream to bad liver, mucous membranes, taken much the arterial phase. Diagnostic and Laboratory Test Reference. Many hospitals opt for early postnatal discharge of newborns with a potential risk of readmission for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. During prolonged storage in the gallbladder, it down be an indication of hepatocellular or obstructive jaundice. Cholelithiasis, RD, carotenoids also contribute since the icteric index so the index may figure a poorer estimate my total bilirubin concentration in random species. Advancement of dermal icterus in the jaundiced newborn. Noorulla F, Freese DK, im not sure. The hepatocytes secrete this fraction. Alferink LJM, increases in bilirubin are likely due to unconjugated bilirubin. Total bilirubin measures both BU and BC. Exchange transfusion should be considered in a newborn with nonhemolytic jaundice if intensive phototherapy fails to junk the bilirubin level. There at be a blockage to combine liver, in grazing animals, Sivieri EM. There own two types of bilirubin in the blood. -

Bilirubin Reference Range for Adults

Bilirubin Reference Range For Adults Epidotic Puff levels or elates some semicircle dismally, however ship-rigged Hilton glom unashamedly or spared. Which Saundra disproved so pinnately that Ambrosius discomposed her cackles? Park ethicizing slowly. How do complete conjugation process and ast and from where it is free subscriptions for you can be encountered on laboratory results along with missing data. Looking for later Physician? It indicates the ability to graduate an email. Bilirubin is ultimately processed by her liver and allow its elimination from such body. Have you got a diagnosis of liver disease or symptoms. Indirect Bilirubin University Hospitals. Do not filtered from a type is for getting checked out, questions about all students with metabolic syndrome, drugs that it is collected by highly elevated. How do normal values for bilirubin in a newborn compare for those in fact adult Levels are higher in the newborn The total bilirubin in a 3-5 day was full term. In newborns, bilirubin levels are higher for the loan few days of life. Thanks for rich feedback! There is converted into a hierarchical coding system management, allergic reaction that affect lab profiles can eat radishes or equilibrium. Drugs may be less useful information on liver profile shows that entered my alcohol. Differential Diagnosis Physical Examination Evaluation References. Name for a sensitive imaging scans are slightly different gp practice committee on my dog with. It school a very senior level of bilirubin and flow the digest of hyper Adults Total BilirubinmgdL Normal Reference Range 03 to 10 mgdLmmolL Normal. Physiological jaundice results for adults unless otherwise normal laboratory test different lab tests run? Bilirubin is then removed from the body through their stool feces and gives stool its normal color. -

Evidence of Hemolysis in Pigs Infected with Highly Virulent African Swine Fever Virus

Veterinary World, EISSN: 2231-0916 RESEARCH ARTICLE Available at www.veterinaryworld.org/Vol.9/December-2016/13.pdf Open Access Evidence of hemolysis in pigs infected with highly virulent African swine fever virus Zaven Karalyan1, Hovakim Zakaryan1, Elina Arakelova2, Violeta Aivazyan2, Marina Tatoyan1, Armen Kotsinyan1, Roza Izmailyan1 and Elena Karalova1 1. Laboratory of Cell Biology and Virology, Institute of Molecular Biology of NAS RA, 7 Hasratyan Street, 0014 Yerevan, Armenia; 2. Laboratory of Human Genomics and Immunomics, Institute of Molecular Biology of NAS RA, 7 Hasratyan Street, 0014 Yerevan, Armenia. Corresponding author: Zaven Karalyan, e-mail: [email protected], HZ: [email protected], EA: [email protected], VA: [email protected], MT: [email protected], AK: [email protected], RI: [email protected], EK: [email protected] Received: 29-08-2016, Accepted: 12-11-2016, Published online: 14-12-2016 doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2016.1413-1419 How to cite this article: Karalyan Z, Zakaryan H, Arakelova E, Aivazyan V, Tatoyan M, Kotsinyan A, Izmailyan R, Karalova E (2016) Evidence of hemolysis in pigs infected with highly virulent African swine fever virus, Veterinary World, 9(12): 1413-1419. Abstract Aim: The research was conducted to understand more profoundly the pathogenetic aspects of the acute form of the African swine fever (ASF). Materials and Methods: A total of 10 pigs were inoculated with ASF virus (ASFV) (genotype II) in the study of the red blood cells (RBCs), blood and urine biochemistry in the dynamics of disease. Results: The major hematological differences observed in ASFV infected pigs were that the mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, and hematocrits were significantly decreased compared to controls, and the levels of erythropoietin were significantly increased. -

URINE Urine Is a Liquid That Removes Many Substances in the Form Of

URINE Urine is a liquid that removes many substances in the form of molten or suspended particles from the organism. Substances in normal urine Organic Substances Inorganic Substances (20-25 g) (35-45 g) Nitrogenous Non-nitrogenous Cation Anions Compounds Compounds Urea Glucuronic acid Na+ CI− Uric Acid Citric acid K+ Phosphates +2 −2 Hippuric acid Oxalic acid Ca SO4 Creatinine Lactic acid Mg+2 Br− Ammonia Phenols Copper F− Amino acids Cresols Iron I− Purines Vitamins Enzymes Hormones Vitamins Hormones Specific reactions of some of the above-mentioned substances in a normal urine are known. Based on these reactions, it can be understood whether a fluid is a urine. Urine is: A liquid that gives chloride, sulfate, creatinine and urea reactions, and when the water is evaporated, leaves a rich residue of urea, uric acid and hippuric 49 acid. Understanding whether a liquid is urine or not: •Determination of chloride, sulfate, urea, creatinine in liquid •Search for urea in the residual after the liquid has been evaporated Experiments will be carried out by sampling 2-3 ml into the tube. 1-Determination of chloride Liquid + a few drops of concentrated HNO3+ 2-3 drops of 5% AgNO3→ AgCl ↓ (white sediment) Nitric acid (HNO3 prevents the precipitation of phosphate and carbonate which could be precipitated by silver nitrate (AgNO3). 2-Determination of sulphate Liquid + several drops of 10% HCl + 2-3 drops BaCl2→ BaSO4↓ (white sediment) 3-Determination of urea Searched by two experiments: • Sodium hypobromite (NaOBr) • Using the enzyme urease a- Sodium -

What Tells Routine Urine Examination

What tells Routine Urine Examination Specific gravity Animals producing large volume of urine have low specific gravity where as very small volume of urine has high specific gravity (animal with oliguric acute intrarenal failure that has a low urine volume and low specific gravity). Fluid therapy, diuretics, glucocorticoids and diet affect urine specific gravity. Sp. gr. is higher in morning samples and was observed to decrease as the age of the animal increased. Urine pH Acidic urine: - ingestion of meat, respiratory and metabolic acidosis, severe vomition, severe diarrhea, starvation, pyrexia, other protein catabolic states and administration of urinary acidifiers. Alkaline urine:- recent meal, ingestion of alkali, UTI with urease-producing bacteria, renal tubular acidosis, diets rich in vegetables and cereals, and metabolic and respiratory alkalosis, urine allowed to stand open to air at room temperature. Proteinuria Trace or 1+ protein level is considered normal with a specific gravity greater than 1.035. Highly alkaline urine (>8) can produce a false positive result. The most common cause of inflammatory proteinuria is urinary tract infection (UTI). If hematuria and pyouria is ruled out, then another urinalysis should be performed to determine the persistent proteinuria. Transient proteinuria is due to strenuous exercise, fever, seizures, and venous congestion of the kidneys and it is insignificant. Persistent proteinuria is usually due to glomerulonephritis or amyloidosis. The urine protein: creatinine ratio helps to determine the magnitude and significance of proteinuria. Glucosuria False negative results come due to large quantity of ascorbic acid, contaminated with H2O2, Cl, hypochlorite, formaldehyde or fluorides in urine. Cats with cystitis may give a false positive reaction. -

Urine Examination Findings in Apparently Healthy New School

of Ch al ild rn u H o e a J l t A h S of Ch al ild rn u H o e a J l t A h S of Ch al ild ARTICLE rn u H o e a J l t A h Urine examination findings in S apparently healthy new school entrants in Jos, Nigeria Francis Akor, MB BS, FWACP (Paed) Seline N Okolo, MB BS, FMCP (Paed), FWACP (Paed) Emmanuel I Agaba, MB BS, FWACP (Med) Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria Angela Okolo, MD, FMCP (Paed), FWACP (Paed) University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria Corresponding author: F Akor ([email protected]) Background. Urinalysis as a part of medical examination of fitness in schoolchildren is useful in detecting abnormalities that could identify early disease conditions. Objective. To describe the urine examination findings in apparently healthy newly enrolled primary school entrants in Jos, Plateau. Methods. Through a multistage stratified randomisation procedure, 650 apparently healthy pupils were selected to have a complete physical examination in the morning with mid-stream urine samples collection. The urine samples were examined for abnormalities using dipsticks. Results. There were 301 boys and 349 girls (ratio 0.9:1). Their mean age was 6.6±1.3 years (range 5 - 12 years). Urinary abnormalities were present in 63 (9.6%) of the subjects, with most in the 6 - 8-year age group. Proteinuria was the most common abnormality, detected in 23 (3.5%), and next, urobilinogen in 12 (1.8%) subjects. The latter was significantly greater in male and private school subjects (p=0.03).