Soil Acidification in Relation to Salinisation and Natural Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Acid Sulfate Soils by Groundwater Manipulation Bruce Geoffrey Blunden University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2000 Management of acid sulfate soils by groundwater manipulation Bruce Geoffrey Blunden University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Blunden, Bruce Geoffrey, Management of acid sulfate soils by groundwater manipulation, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Engineering, University of Wollongong, 2000. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1834 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] MANAGEMENT OF ACID SULFATE SOILS BY GROUNDWATER MANIPULATION A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by BRUCE GEOFFREY BLUNDEN B.Nat Res. (Hons), M.Eng. Faculty of Engineering October 2000 AFFIRMATION I, Bruce Blunden, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Engineering, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Bruce Blunden. n PUBLICATIONS RELATED TO THIS RESEARCH Blunden, B. and Indraratna, B. (2000). Evaluation of Surface and Groundwater Management Strategies for Drained Sulfidic Soil using Numerical Models. Australian Journal of Soil Research 38, 569-590 Blunden, B. and Indraratna, B. (2000). Pyrite Oxidation Model for Assessing Groundwater management Strategies in Acid Sulphate Soils. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, (in press). Indraratna, B. and Blunden, B. (1999). Nature and Properties of Acid Sulphate Soils in Drained Coastal lowland in NSW, Australian Geomechanics Journal, 34(1), 61-78. -

Acid Sulfate Soil Materials

Site contamination —acid sulfate soil materials Issued November 2007 EPA 638/07: This guideline has been prepared to provide information to those involved in activities that may disturb acid sulfate soil materials (including soil, sediment and rock), the identification of these materials and measures for environmental management. What are acid sulfate soil materials? Acid sulfate soil materials is the term applied to soils, sediment or rock in the environment that contain elevated concentrations of metal sulfides (principally pyriteFeS2 or monosulfides in the form of iron sulfideFeS), which generate acidic conditions when exposed to oxygen. Identified impacts from this acidity cause minerals in soils to dissolve and liberate soluble and colloidal aluminium and iron, which may potentially impact on human health and the environment, and may also result in damage to infrastructure constructed on acid sulfate soil materials. Drainage of peaty acid sulfate soil material also results in the substantial production of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O). The oxidation of metal sulfides is a function of natural weathering processes. This process is slow however, and, generally, weathering alone does not pose an environmental concern. The rate of acid generation is increased greatly through human activities which expose large amounts of soil to air (eg via excavation processes). This is most commonly associated with (but not necessarily confined to) mining activities. Soil horizons that contain sulfides are called ‘sulfidic materials’ (Isbell 1996; Soil Survey Staff 2003) and can be environmentally damaging if exposed to air by disturbance. Exposure results in the oxidation of pyrite. This process transforms sulfidic material to sulfuric material when, on oxidation, the material develops a pH 4 or less (Isbell 1996; Soil Survey Staff 2003). -

Soil Acidification

viti-notes [grapevine nutrition] Soil acidifi cation Viti-note Summary: Characteristics of acidic soils • Soil pH Calcium and magnesium are displaced • Soil acidifi cation in by aluminium (Al3+) and hydrogen (H+) vineyards and are leached out of the soil. Acidic soils below pH 6 often have reduced • Characteristics of acidic populations of micro-organisms. As soils microbial activity decreases, nitrogen • Acidifying fertilisers availability to plants also decreases. • Effect of soil pH on Sulfur availability to plants also depends rate of breakdown of on microbial activity so in acidic soils, ammonium to nitrate where microbial activity is reduced, Figure 1. Effect of soil pH on availability of minerals sulfur can become unavailable. (Sulfur • Management of defi ciency is not usually a problem for acidifi cation Soil pH vineyards as adequate sulfur can usually • Correction of soil pH All plants and soil micro-organisms have be accessed from sulfur applied as foliar with lime preferences for soil within certain pH fungicides). ranges, usually neutral to moderately • Strategies for mature • Phosphorus availability is reduced at acid or alkaline. Soil pH most suitable vines low pH because it forms insoluble for grapevines is between 5.5 and 8.5. phosphate compounds with In this range, roots can acquire nutrients aluminium, iron and manganese. from the soil and grow to their potential. As soils become more acid or alkaline, • Molybdenum is seldom defi cient in grapevines become less productive. It is neutral to alkaline soils but can form important to understand the impacts of insoluble compounds in acid soils. soil pH in managing grapevine nutrition, • In strongly acidic soil (pH <5), because the mobility and availability of aluminium may become freely nutrients is infl uenced by pH (Figure 1). -

Understanding and Managing Irrigated Acid Sulfate and Salt-Affected Soils

This handbook was part-funded by a grant from the South Australian River Murray Sustainability Program and delivered by Primary Industries and Regions South Australia between 2014 and 2016. We also acknowledge funding support and assistance from the Murray-Darling Basin Authority for field monitoring investigations between 2008 and 2011. Share this book Thehigh-quality paperback edition of this book is available for purchase online at https://shop. adelaide.edu.au/ Suggested citation: Fitzpatrick RW, Mosley LM, and Cook FJ. (2017). Understanding and managing irrigated acid sulfateand salt affectedsoils: A handbook for the Lower Murray Reclaimed Irrigation Area. Acid SulfateSoils Centre Report: ASSC_086. University of Adelaide Press, Adelaide. DO I: https:/ / doi.org/ 10.20851/ murray-soils. License: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 UNDERSTANDING AND MANAGING IRRIGATED ACID SULFATE AND SALT-AFFECTED SOILS A handbook for the Lower Murray Reclaimed Irrigation Area by Rob W Fitzpatrick • Luke M Mosley • Freeman J Cook Acid Sulfate Soils Centre (ASSC), The University of Adelaide Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press Barr Smith Library The University of Adelaide South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes peer reviewed scholarly books. It aims to maximise access to the best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2017 Rob W Fitzpatrick, Luke M Mosley, Freeman J Cook This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. -

Soil Acidification

Soil Acidification and Pesticide Management pH 5.1 November 14, 2018 MSU Pesticide Education Program pH 3.8 Image courtesy Rick Engel Clain Jones [email protected] 406-994-6076 MSU Soil Fertility Extension What happened here? Image by Sherrilyn Phelps, Sask Pulse Growers Objectives Specifically, I will: 1. Show prevalence of acidification in Montana (similar issue in WA, OR, ID, ND, SD, CO, SK and AB) 2. Review acidification’s cause and contributing factors 3. Show low soil pH impact on crops 4. Explain how this relates to efficacy and persistence of pesticides (specifically herbicides) 5. Discuss steps to prevent or minimize acidification Prevalence: MT counties with at least one field with pH < 5.5 Symbol is not on location of field(s) 40% of 20 random locations in Chouteau County have pH < 5.5. Natural reasons for low soil pH . Soils with low buffering capacity (low soil organic matter, coarse texture, granitic rather than calcareous) . Historical forest vegetation soils < pH than historical grassland . Regions with high precipitation • leaching of nitrate and base cations • higher yields, receive more N fertilizer • often can support continuous cropping and N each yr Agronomic reasons for low soil pH • Nitrification of ammonium-based N fertilizer above plant needs - + ammonium or urea fertilizer + air + H2O→ nitrate (NO3 ) + acid (H ) • Nitrate leaching – less nitrate uptake, less root release of basic - - anions (OH and HCO3 ) to maintain charge balance • Crop residue removal of Ca, Mg, K (‘base’ cations) • No-till concentrates acidity where N fertilizer applied • Legumes acidify their rooting zone through N-fixation. Perennial legumes (e.g., alfalfa) more than annuals (e.g., pea), but much less than fertilization of wheat. -

Management Options for Acid Sulfate Soils in the Lower Murray Lakes, South Australia

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR ACID SULFATE SOILS IN THE LOWER MURRAY LAKES, SOUTH AUSTRALIA Stage 2 - Preliminary Assessment of Prevention, Control and Treatment Options prepared for PRIMARY INDUSTRIES AND RESOURCES SOUTH AUSTRALIA RURAL SOLUTIONS SA & THE DEPARTMENT FOR ENVIRONMENT AND HERITAGE, SOUTH AUSTRALIA by EARTH SYSTEMS Environment – Water – Sustainability December, 2008 MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR ACID SULFATE SOILS IN THE LOWER MURRAY LAKES STAGE 2 – PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF PREVENTION, CONTROL AND TREATMENT OPTIONS Earth Systems DECEMBER, 2008 EARTH SYSTEMS DISTRIBUTION RECORD Copy No. Company / Position Name 1 Primary Industries and Resources South Australia, Martin Carter Rural Solutions SA 2 Department for Environment and Heritage Russell Seaman 3 Primary Industries and Resources South Australia Jason Higham 4 Environment Protection Authority SA Luke Mosley 5 Earth Systems Library RSSA082305_Report_Rev1 Page 2 MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR ACID SULFATE SOILS IN THE LOWER MURRAY LAKES STAGE 2 – PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT OF PREVENTION, CONTROL AND TREATMENT OPTIONS Earth Systems DECEMBER, 2008 EARTH SYSTEMS DOCUMENT REVISION LIST Revision Revision Date Description of Approved By Status/Number Revision 0 December 2008 Draft Report Jeff Taylor 1 December 2008 Final Report Jeff Taylor This report is not to be used for purposes other than that for which it was intended. Environmental conditions change with time. The site conditions described in this report are based on observations made during the site visit and on subsequent monitoring results. Earth Systems Pty Ltd does not imply that the site conditions described in this report are representative of past or future conditions. Where this report is to be made available, either in part or in its entirety, to a third party, Earth Systems Pty Ltd reserves the right to review the information and documentation contained in the report and revisit and update findings, conclusions and recommendations. -

Nitrogen Deposition Contributes to Soil Acidification in Tropical Ecosystems

Global Change Biology Global Change Biology (2014), doi: 10.1111/gcb.12665 Nitrogen deposition contributes to soil acidification in tropical ecosystems XIANKAI LU1 , QINGGONG MAO1,2,FRANKS.GILLIAM3 ,YIQILUO4 and JIANGMING MO 1 1Key Laboratory of Vegetation Restoration and Management of Degraded Ecosystems, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China, 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China, 3Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University, Huntington, WV 25755-2510, USA, 4Department of Microbiology and Plant Biology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK 73019, USA Abstract Elevated anthropogenic nitrogen (N) deposition has greatly altered terrestrial ecosystem functioning, threatening eco- system health via acidification and eutrophication in temperate and boreal forests across the northern hemisphere. However, response of forest soil acidification to N deposition has been less studied in humid tropics compared to other forest types. This study was designed to explore impacts of long-term N deposition on soil acidification pro- cesses in tropical forests. We have established a long-term N-deposition experiment in an N-rich lowland tropical for- À1 À1 est of Southern China since 2002 with N addition as NH4NO3 of 0, 50, 100 and 150 kg N ha yr . We measured soil acidification status and element leaching in soil drainage solution after 6-year N addition. Results showed that our study site has been experiencing serious soil acidification and was quite acid-sensitive showing high acidification < < (pH(H2O) 4.0), negative water-extracted acid neutralizing capacity (ANC) and low base saturation (BS, 8%) through- out soil profiles. Long-term N addition significantly accelerated soil acidification, leading to depleted base cations and decreased BS, and further lowered ANC. -

Lowering Soil Ph for Horticulture Crops

PURDUE EXTENSION HO-241-W Commercial Greenhouse and Nursery Production Lowering Soil pH for Horticulture Crops Purdue Horticulture and Michael V. Mickelbart and Kelly M. Stanton, Landscape Architecture Purdue Horticulture and Landscape Architecture www.ag.purdue.edu/HLA Steve Hawkins and James Camberato, Purdue Agronomy Purdue Agronomy www.ag.purdue.edu/AGRY The pH scale measures the acidity or alkalinity of a solution. The scale extends from 0 (a very strong acid) to 14 (a very strong base or highly alkaline). The middle of the scale, 7, is neutral, neither acidic nor basic. Soil pH is important because it affects the availability of nutrients in the rooting zone. This publication explains when lowering soil pH is important for commercial producers and recommends practices to safely and effectively lower soil pH. For more about soil pH, see Purdue Extension publication HO-240-W, Commercial Greenhouse and Nursery Production: Soil pH (available from the Purdue Extension Education Store, www. the-education-store.com). When it comes to soil pH, an accurate diagnosis is essential. Before making any changes, test your soil pH. Purdue Extension provides a list of commercial soil testing labs at: www.ag.purdue.edu/agry/extension/Pages/soil-testing-labs.aspx Why Lower Soil pH? Some plants (such as blueberries or azaleas) are adapted to grow in acid soils — even as low as pH 4.5. If you are trying to grow them you may want a soil pH less than 6, but remember that even acid-loving plants have their limits. Table 1. Effects of soil amendments on pH. -

Chemical and Biochemical Properties of Soils Developed from Different Lithologies in Northwestern Spain (Galicia)

Article Chemical and Biochemical Properties of Soils Developed from Different Lithologies in Northwestern Spain (Galicia) Valeria Cardelli 1,*, Stefania Cocco 1, Alberto Agnelli 2, Serenella Nardi 3, Diego Pizzeghello 3, Maria J. Fernández‐Sanjurjo 4 and Giuseppe Corti 1 1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, 60131, Italy; [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (G.C.) 2 Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Perugia, 06121, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Agronomy, Food, Natural Resources, Animals and the Environment, Università degli Studi di Padova, Legnaro, 35020, Italy; [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (D.P.) 4 Department of Soil and Agronomic Chemistry, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Lugo, 27001, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39‐338‐599‐6867 Academic Editors: Adele Muscolo and Miroslava Mitrovic Received: 15 March 2017; Accepted: 19 April 2017; Published: 22 April 2017 Abstract: Physical and chemical soil properties are generally correlated with the parent material, as its composition may influence the pedogenetic processes, the content of nutrients, and the element biocycling. This research studied the chemical and biochemical properties of the A horizon from soils developed on different rocks like amphibolite, serpentinite, phyllite, and granite under a relatively similar climatic regime from Galicia (northwest Spain). In particular, the effect of the parent material on soil evolution, organic carbon sequestration, and the hormone‐like activity of humic and fulvic acids were tested. Results indicated that all the soils were scarcely fertile because of low concentrations of available P, exchangeable Ca (except for the soils on serpentinite and phyllite), and exchangeable K, but sequestered relevant quantities of organic carbon. -

New Approaches to Agricultural Land Drainage

ge Syst Gurovich and Oyarce, Irrigat Drainage Sys Eng 2015, 4:2 ina em a s r D E DOI: 10.4172/2168-9768.1000135 n & g i n n o e i t e a r i g n i r g r Irrigation & Drainage Systems Engineering I ISSN: 2168-9768 Research Article Open Access New Approaches to Agricultural Land Drainage: A Review Luis Gurovich* and Patricio Oyarce Departamento de Fruticultura y Enología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Santiago, Chile Abstract A review on agricultural effects of restricted soil drainage conditions is presented, related to soil physical, chemical and biological properties, soil water availability to crops and its effects on crop development and yield, soil salinization hazards, and the differences on drainage design main objectives in soils under tropical and semi-arid water regime conditions. The extent and relative importance of restricted drainage conditions in Agriculture, due to poor irrigation management is discussed, and comprehensive studies for efficient drainage design and operation required are outlined, as related to data gathering, revision and analysis about geology, soil science, topography, wells, underground water dynamics under field conditions, the amount, intensity and frequency of precipitations, superficial flow over the area to be drained, climatic characteristics, irrigation management and the phenology of crop productive development stages. These studies enable determining areas affected by drainage restrictions, as well as defining the optimal drainage net design and performance, in order to sustain soil conditions suitable to crops development. Keywords: Restricted drainage; Drainage studies; Drainage design As a result of plant metabolic disorders, caused by conditions of parameters total or partial anoxia near the roots, resulting from deficient drainage conditions, a decrease in crop production often occurs [8,15,16,18]. -

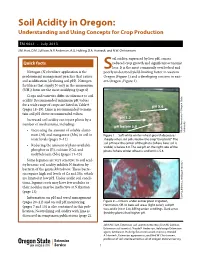

Soil Acidity in Oregon: Understanding and Using Concepts for Crop Production

Soil Acidity in Oregon: Understanding and Using Concepts for Crop Production EM 9061 • July 2013 J.M. Hart, D.M. Sullivan, N.P. Anderson, A.G. Hulting, D.A. Horneck, and N.W. Christensen oil acidity, expressed by low pH, causes Quick facts reduced crop growth and significant economic Sloss. It is the most commonly overlooked and Nitrogen (N) fertilizer application is the poorly understood yield-limiting factor in western predominant management practice that causes Oregon (Figure 1) and a developing concern in east- soil acidification (declining soil pH). Nitrogen ern Oregon (Figure 2). fertilizers that supply N only in the ammonium (NH4) form are the most acidifying (page 6). Crops and varieties differ in tolerance to soil acidity. Recommended minimum pH values for a wide range of crops are listed in Table 9 pH 5.6 (pages 18–19). Lime is recommended to main- tain soil pH above recommended values. pH 5.2 Increased soil acidity can injure plants by a number of mechanisms, including: pH below 5.0 • Increasing the amount of soluble alumi- State Nicole © Oregon Anderson, University num (Al) and manganese (Mn) in soil to Figure 1.—Soft white winter wheat growth decreases toxic levels (pages 9–11) sharply when soil pH is below the crop “threshold.” The soil pH near the center of the photo (where bare soil is • Reducing the amount of plant-available visible) is below 5.0. The soil pH on the right side of the phosphorus (P), calcium (Ca), and photo (where winter wheat is uniform) is 5.6. molybdenum (Mo) (pages 11–13) Some legumes are very sensitive to soil acid- ity because soil acidity inhibits N fixation by bacteria of the genus Rhizobium. -

Groundwater Interactions with Acid Sulfate Soil: a Case Study in Torbay

Government of Western Australia Department of Water Groundwater interactions with acid sulfate soil: a case study in Torbay, Western Australia A technical report for the project Tackling acid sulfate soils on the WA coast Looking after all our water needs technical series Report no. WST 17 October 2009 Groundwater interactions with acid sulfate soil: a case study in Torbay, Western Australia A technical report for the project: Tackling acid sulfate soils on the WA coast Looking after all our water needs KL Kilminster Department of Water Water Science Technical series Report no. 17 October 2009 Groundwater interactions with acid sulfate soil: a case study in Torbay, Western Australia Department of Water 168 St Georges Terrace Perth Western Australia 6000 Telephone +61 8 6364 7600 Facsimile +61 8 6364 7601 www.water.wa.gov.au © Government of Western Australia 2009 October 2009 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Water. ISSN 1836-2869 (print) ISSN 1836-2877 (online) ISBN 978-1-921675-65-2 (print) ISBN 978-1-921675-33-1 (online) Acknowledgements This project was funded by the Australian Federal and Western Australian governments. The Department of Water would like to thank the following people for their contribution to this publication. This report was written by Dr Kieryn Kilminster.