The Sandwich to Dover Turnpike, 1833-1874

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CHALK UPLANDS OF NORTHWEST EUROPE The Chilterns, Pegsdon, Bedfordshire (photograph L. Blundell) Lesley Blundell UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD September 2019 2 I, Lesley Blundell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 3 4 Abstract Our understanding of early human behaviour has always been and continues to be predicated on an archaeological record unevenly distributed in space and time. More than 80% of British Lower-Middle Palaeolithic findspots were discovered during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the majority from lowland fluvial contexts. Within the British planning process and some academic research, the resultant findspot distributions are taken at face value, with insufficient consideration of possible bias resulting from variables operating on their creation. This leads to areas of landscape outside the river valleys being considered to have only limited archaeological potential. This thesis was conceived as an attempt to analyse the findspot data of the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic record of the Chalk uplands of southeast Britain and northern France within a framework complex enough to allow bias in the formation of findspot distribution patterns and artefact preservation/discovery opportunities to be identified and scrutinised more closely. Taking a dynamic, landscape = record approach, this research explores the potential influence of geomorphology, 19th/early 20th century industrialisation and antiquarian collecting on the creation of the Lower- Middle Palaeolithic record through the opportunities created for artefact preservation and release. -

Sandwich Bay and Hacklinge Marshes Districts

COUNTY: KENT SITE NAME: SANDWICH BAY AND HACKLINGE MARSHES DISTRICTS: THANET/DOVER Status: Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) notified under Section 28 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 Local Planning Authority: THANET DISTRICT COUNCIL/DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL National Grid Reference: TR 353585 Area: 1756.5 (ha.) 4338.6 (ac.) Ordnance Survey Sheet 1:50,000: 179 1:10,000: TR 35 NE, NW, SE, SW; TR 36 SW, SE Date Notified (Under 1949 Act): 1951 Date of Last Revision: 1981 Date Notified (Under 1981 Act): 1984 (part) Date of Last Revision: 1994 1985 (part) 1990 Other Information: Parts of the site are listed in ÔA Nature Conservation ReviewÕ and in ÔA Geological Conservation ReviewÕ2. The nature reserve at Sandwich Bay is owned jointly by the Kent Trust for Nature Conservation, National Trust and Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. The site has been extended to include a Kent Trust designated Site of Nature Conservation Interest known as Richborough Pasture and there are several other small amendments. Reasons for Notification: This site contains the most important sand dune system and sandy coastal grassland in South East England and also includes a wide range of other habitats such as mudflats, saltmarsh, chalk cliffs, freshwater grazing marsh, scrub and woodland. Associated with the various constituent habitats of the site are outstanding assemblages of both terrestrial and marine plants with over 30 nationally rare and nationally scarce species, having been recorded. Invertebrates are also of interest with recent records including 19 nationally rare3, and 149 nationally scarce4 species. These areas provide an important landfall for migrating birds and also support large wintering populations of waders, some of which regularly reach levels of national importance5. -

A Guide to Parish Registers the Kent History and Library Centre

A Guide to Parish Registers The Kent History and Library Centre Introduction This handlist includes details of original parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts held at the Kent History and Library Centre and Canterbury Cathedral Archives. There is also a guide to the location of the original registers held at Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre and four other repositories holding registers for parishes that were formerly in Kent. This Guide lists parish names in alphabetical order and indicates where parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts are held. Parish Registers The guide gives details of the christening, marriage and burial registers received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish catalogues in the search room and community history area. The majority of these registers are available to view on microfilm. Many of the parish registers for the Canterbury diocese are now available on www.findmypast.co.uk access to which is free in all Kent libraries. Bishops’ Transcripts This Guide gives details of the Bishops’ Transcripts received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish handlist in the search room and Community History area. The Bishops Transcripts for both Rochester and Canterbury diocese are held at the Kent History and Library Centre. Transcripts There is a separate guide to the transcripts available at the Kent History and Library Centre. These are mainly modern copies of register entries that have been donated to the -

West Studdal Farm, West Studdal, Nr Dover, Kent

Please reply to We are also at Romney House 9 The Fairings Monument Way Oaks Road Orbital Park Tenterden, Ashford TN24 0HB TN30 6QX 01233 506260 01580 766766 Our Ref: F2523A Frms nd Lnd April 2019 Dear Sir/Madam West Studdal Farm, West Studdal, Nr Dover, Kent We have pleasure in enclosing the brochure for West Studdal Farm. The farm is located in an unspoilt downland location, yet at the same time easily accessible to Canterbury, Deal, Sandwich and Dover. The property comprises an impressive seven bedroom unlisted house, a pair semi-detached cottages, modern and traditional farm buildings with potential subject to planning permission and productive Grade 2 and 3 arable land together with woodland and extending to a total of about 453.83 acres (183.66 hectares). The farm is for sale as a whole or in up to 10 lots and the price guides for the individual lots are listed below: Lot 1 West Studdal Farm Price Guide: £1.35 million About 18.14 acres (7.34 hectares) (One million three hundred and fifty thousand pounds) Lot 2 1 West Studdal Farm Cottage Price Guide: £180,000 (One hundred and eighty thousand pounds) Lot 3 2 West Studdal Farm Cottage Price Guide: £300,000 (Three hundred thousand pounds) Lot 4 West Studdal Farmland Price Guide: £1.4 million About 164.52 acres (66.58 hectares) (One million four hundred thousand pounds) Lot 5 Arable land west of Willow Woods Road Price Guide: £140,000 About 14.18 acres (5.74 hectares) (One hundred and forty thousand pounds) Continued Country Houses The Villages Ashford Homes Tenterden Homes Equestrian Homes Farms and Land Development Land Residential Lettings Hobbs Parker Estate Agents is a trading style of Hobbs Parker Ventures Limited, a company registered in England and Wales under the number 7392816, whose registered office is Romney House, Monument Way, Orbital Park, Ashford, Kent TN24 0HB. -

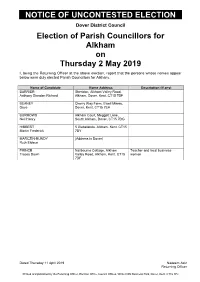

Parish Council (Uncontested)

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Dover District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Alkham on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Alkham. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BARRIER Sheridan, Alkham Valley Road, Anthony Standen Richard Alkham, Dover, Kent, CT15 7DF BEANEY Cherry Way Farm, Ewell Minnis, Dave Dover, Kent, CT15 7EA BURROWS Alkham Court, Meggett Lane, Neil Henry South Alkham, Dover, CT15 7DG HIBBERT 5 Glebelands, Alkham, Kent, CT15 Martin Frederick 7BY MARCZIN-BUNDY (Address in Dover) Ruth Eldeca PRINCE Nailbourne Cottage, Alkham Teacher and local business- Tracey Dawn Valley Road, Alkham, Kent, CT15 woman 7DF Dated Thursday 11 April 2019 Nadeem Aziz Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Election Office, Council Offices, White Cliffs Business Park, Dover, Kent, CT16 3PJ NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Dover District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ash on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ash. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) CHANDLER Hadaways, Cop Street, Ash, Peter David Canterbury, CT3 2DL ELLIS 60A The Street, Ash, Canterbury, Reginald Kevin Kent, CT3 2EW HARRIS-ROWLEY (Address in Dover) Andrew Raymond LOFFMAN (Address in Dover) Jeffrey Philip PORTER 38 Sandwich Rd, Ash, Canterbury, Martin -

Dover and Deal Conservative Association

4/9/2018 Local Government Boundary Commission for England Consultation Portal Dover District Personal Details: Name: Keith Single E-mail: Postcode: Organisation Name: Dover and Deal Conservative Association Feature Annotations 2:2: NNorthorth WestWest DealDeal andand SholdenSholden 3:3: SSouthouth DDealeal aandnd CCastleastle 44:: MMaxton,axton, ElmsElms VValeale andand TTowerower HHamletsamlets Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database rights 2013. Map Features: Annotation 2: North West Deal and Sholden Annotation 3: South Deal and Castle Annotation 4: Maxton, Elms Vale and Tower Hamlets Comment text: Dover and Deal Conservative Association largely supports the proposal submitted by Dover District Council but makes different proposals in some wards and submits additional evidence. In Dover, we concur that it would be inappropriate and unnecessary to have wards which cross the external boundaries of the Dover Town Council area as electoral equality can be maintained without diminishing the delivery of convenient and effective local government that cross border wards might cause. We considered a ward encompassing all of the seafront area and the activities of the Port of Dover but the electors in that area have no significant interaction with port operations there being no concentration of employment in maritime trades which instead draw their workers from across Dover District and beyond. Instead we support the inclusion of all town centre activities in one ward which will enable members representing that ward to better understand the specific issues such an area generates. To create a ward that includes the somewhat separate community of Aycliffe with enough electors to form a ward we support its combination with the distinctive, concentrated and cohesive Clarendon area. -

04 December 2020

Registered applications for week ending 04/12/2020 DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL ASH 20/00284 63 Sandwich Road Hybrid application: (Phase 1) LUR Ash Full application for erection CT3 2AH of 18no. dwellings and 4no. flats, access, parking, associated infrastructure and landscaping; (Phase 2) Outline application for a building comprising 10no. flats and 5no. dwellings (with all matters reserved except access and layout) (amended plans) AYLESHAM 20/01087 40 Newman Road Erection of front and rear VH Aylesham dormer windows to facilitate CT3 3BY loft conversion DEAL 20/01345 Victoria Hospital Installation of 4no. ALPI London Road condenser units, an access Deal ramp and the replacement of CT14 9UA fire exit door 20/01265 195 Middle Deal Road Conversion of coach house VH Deal into ancillary CT14 9RL accommodation including installation of 2no. rooflights 20/01295 35 Links Road Conversion of garage to ALPI Deal habitable accommodation, CT14 6QF access ramp to front elevation and alterations to rear windows and door 1 Registered applications for week ending 04/12/2020 DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL 20/01230 4-6 Park Street Part change of use from AW Deal Professional Services (Use CT14 6AQ Class A2) to Residential (Use Class C3) and erection of two-storey rear extension. Insertion of 2no. rear windows into second floor of non-domestic building 20/01373 9 Darracott Close Erection of a side extension VH Deal and garage (existing garage CT14 9PU and lean-to to be demolished) DENTON WITH WOOTTON 20/00908 Lodge Lees Farm Change of use and BK Lodge Lees Road conversion of barn to Denton dwellinghouse to include CT4 6NS insertion of 22 no. -

Economic Impact of Tourism Dover Town - 2019 Results

Commissioned by: Visit Kent Economic Impact of Tourism Dover Town - 2019 Results November 2020 Produced by: Destination Research www.destinationresearch.co.uk Contents Page Introduction and Contextual Analysis 3 Headline Figures 6 Volume of Tourism 8 Staying Visitors in the county context 9 Staying Visitors - Accommodation Type 10 Trips by Accommodation Nights by Accommodation Spend by Accommodation Staying Visitors - Purpose of Trip 11 Trips by Purpose Nights by Purpose Spend by Purpose Day Visitors 12 Day Visitors in the county context 12 Value of Tourism 13 Expenditure Associated With Trips 14 Direct Expenditure Associated with Trips Other expenditure associated with tourism activity Direct Turnover Derived From Trip Expenditure Supplier and Income Induced Turnover Total Local Business Turnover Supported by Tourism Activity Employment 16 Direct 17 Full time equivalent Estimated actual jobs Indirect & Induced Employment 17 Full time equivalent Estimated actual jobs Total Jobs 18 Full time equivalent Estimated actual jobs Tourism Jobs as a Percentage of Total Employment 18 Appendix I - Cambridge Model - Methodology 20 Economic Impact of Tourism Dover Town - 2019 Results 2 Introduction This report examines the volume and value of tourism and the impact of visitor expenditure on the local economy in 2019 and provides comparative data against the previously published data for Kent (2017). Part of the Interreg Channel EXPERIENCE project, Destination Research was commissioned by Visit Kent to produce 2019 results based on the latest data from national tourism surveys and regionally/locally based data. The results are derived using the Cambridge Economic Impact Model. In its basic form, the model distributes regional activity as measured in national surveys to local areas using ‘drivers’ such as the accommodation stock and occupancy which influence the distribution of tourism activity at local level. -

Shepherd Neame?

-Coastguard-______ P u b O Restaurant www.thecoas+juard. co. uk Between the bottom of the hill and the deep blue sea 111 a location renowned across Kent for its beauty, The Coastguard, Britain’s nearest pub to France, lives up to its reputation for excellent food and drink served with a pleasing informality, the ideal location to relax and drink in the views out to sea. (!ADD’S of Ramsgate and HOPDAKMON feature regularly alongside other award winning ("ask Ales from further a field. Microhreweries are our preference W Keeping our reputation for excellent Cask ik's Ariel Award winning fresh food complimenting Kentish Ales Award winning Cheese boards to compliment beer as well as wine St. Margaret’s Bay 01304 853176 www.thecoastguard.co.uk Printed at Adams the Printers, Dover FREE The Newsletter of the Deal Dover Sandwich & District branch of the Campaign for Real Ale PLEASE TAKE A COPY CAMPAIGN FOR REAL ALE Issue 30 Winter 2006/07 INSIDE WHAT NOW FOR SHEPHERD NEAME? See Page 30 THE NIGHT BEFORE When are you really safe to drive See Page 41 Channel Draught is the Newsletter of the ISSUE 30 Deal Dover Sandwich & Winter 2006/07 District Branch of the Campaign for Real Ale. J anuary 2007 and a Happy New Year to all our readers. Editorial Team The brewing and pubs industry is as ever unsettled (in a ferment as a wag might put it), and in fact it is difficult to Editor & think to think of any other area of business that appears so Advertising embroiled in argument and dissension, so interfered with Martin Atkins and worried over by Government, and so prone to the whims of fashion and taste - and the forthcoming year Editorial Assistants promises to be no exception. -

Water Cycle Study (2020)

Water Cycle Study November 2020 Regulation 18 Consultation on the Draft Local Plan Dover District Local Plan Supporting document Water Cycle Study Executive Summary Dover District Council has started the process of producing a new Local Plan, which will allocate sufficient land for 11,920 new homes in the period up to 2040 as well as making provision for employment space and gypsy and traveller pitches. As part of its Infrastructure evidence base, the Council has produced this Water Cycle Study which aims to draw out and comment on any water-related issues which may affect the delivery of the Plan, as well as providing a summary of the District’s water environment and key water-relevant issues. To do this, the report capitalises on input from both the District’s water providers, Southern Water and Affinity Water, relating to supply and wastewater, as well as the Environment Agency’s advice on abstraction and water quality. Understanding the impact of the growth proposed in the new Local Plan on the existing water infrastructure and the District’s natural environment will be important in enabling sound Policies to be drafted in the Plan. To this end, the Water Cycle Study provides a summary of the Policy and Legislative context for the water environment and identifies water-relevant policies from Dover’s existing development plan documents, before giving an overview of the process leading to the adoption of the new Plan in 2022. The environmental context is described in Chapter 3, before Chapter 4 gives an overview of the external input which informed this Study. -

8 Delfbridge Manor 10 Dover Road, Sandwich

Apartment 8, Delfbridge Manor 10 Dover Road, Sandwich, CT13 0BN £360,000 EPC Rating: B 8 Delfbridge Manor 10 Dover Road, Sandwich Spacious three bedroom ground floor apartment in recently renovated, private gated development. Situation The approach to Apartment 8 is to the left of the main building and the communal entrance hallway Located just half a mile from the centre of this is carefully furnished to provide an impressive medieval town, the property is a short walk from approach to each beautifully presented apartment. the mainline railway station (with Javelin High The south facing garden, surrounded by high Speed service to London) and a "short drive" to timber fencing, has a mixture of lawn, patio and Royal St. George's Golf Club and Sandwich Bay. gravel areas, and some beds planted with a variety of flowering and evergreen bushes and Sandwich provides a variety of shops, restaurants shrubs. A gate gives pedestrian access into the and other amenities whilst further shopping is garden from the side driveway. available in the larger nearby centres of Canterbury, Deal and at Westwood Cross, Broadstairs. Services All main services are understood to be connected The Property to the property. A very appealing apartment with delightful private garden forming part of the private gated Tenure development of Delfbridge Manor with onsite Each apartment will be sold on a 125 year lease parking. The whole property has recently dated from 1st January 2015. The developer’s undergone a major renovation and the emphasis present intention is to convey the freehold of the within this apartment is for light and airy modern building to the residents upon completion of the contemporary styling. -

Draft Local Plan Proposed Site Allocations - Reasons for Site Selection

Topic Paper: Draft Local Plan Proposed Site Allocations - Reasons for Site Selection Dover District Local Plan Supporting document The Selection of Site Allocations for the Draft Local Plan This paper provides the background to the selection of the proposed housing, gypsy and traveller and employment site allocations for the Draft Local Plan, and sets out the reasoning behind the selection of specific site options within the District’s Regional, District, Rural Service, Local Centres, Villages and Hamlets. Overarching Growth Strategy As part of the preparation of the Local Plan the Council has identified and appraised a range of growth and spatial options through the Sustainability Appraisal (SA) process: • Growth options - range of potential scales of housing and economic growth that could be planned for; • Spatial options - range of potential locational distributions for the growth options. By appraising the reasonable alternative options the SA provides an assessment of how different options perform in environmental, social and economic terms, which helps inform which option should be taken forward. It should be noted, however, that the SA does not decide which spatial strategy should be adopted. Other factors, such as the views of stakeholders and the public, and other evidence base studies, also help to inform the decision. The SA identified and appraised five reasonable spatial options for growth (i.e. the pattern and extent of growth in different locations): • Spatial Option A: Distributing growth to the District’s suitable and potentially suitable housing and employment site options (informed by the HELAA and Economic Land Review). • Spatial Option B: Distributing growth proportionately amongst the District’s existing settlements based on their population.