A Landscape Character Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Needs Assessment Sub-Area Profiles

Housing Needs Assessment 2020 Sub-Area Profile Wigan Council Housing Needs Assessment Affordable Housing Need – Wigan Sub-Area Profiles 1 Housing Needs Assessment 2020 Sub-Area Profile Executive Summary Introduction The Wigan Housing Needs Assessment (HNA) 2020 provides the council with up-to-date evidence to support the local plan and its future development. It also provides detailed, robust, and defensible evidence to help determine local housing priorities and to inform the council’s new housing strategy. This research provides an up-to-date analysis of the social, economic, housing, and demographic characteristics of the area. The HNA identifies the type and size of housing needed by tenure and household type. It considers the need for affordable housing and the size, type, and tenure of housing need for specific groups within the borough. The HNA (2020) incorporates: • extensive review, analysis, and modelling of existing (secondary) data. • a comprehensive household survey (Primary Data) • interviews with estate and letting agents operating within the borough; and an online survey of stakeholders. The evidence base for the housing needs assessment (HNA) has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the February 2019 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and associated Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) and the findings provide an up-to-date, robust, and defensible evidence base for policy development, in accordance with Government policy and guidance. Considering the forthcoming new affordable homes programme Wigan Council are keen to see the affordable housing needs of the borough considered when registered providers are seeking to bring forward new schemes. Our HNA provides us with robust data at a sub area level which should allow us to shape the affordable housing offers in each of these areas and meet our defined housing needs. -

IST Journal 2018

The Professional Body for Technical, Specialist, and Managerial Staff Earth sciences BiomedicalMaterials Criminology Physical sciences Interdisciplinary EngineeringApplied science Marine biology Food TechnologyGraphic design Chemistry ForensicsSoftware Textiles Technology Kingfisher House, 90 Rockingham Street Sheffield S1 4EB T: 0114 276 3197 [email protected] F: 0114 272 6354 www.istonline.org.uk Spring 2018 Contents n Editor’s welcome Ian Moulson 2 n Chairman’s view Terry Croft 3 n President’s view Helen Sharman 4 n New members and registrations IST Office 6 n IST organisation IST Office 8 n Joining the IST Kevin Oxley 11 n Vikki Waring: from cupboard to laboratory Andy Connelly 12 n Personal views of equality and diversity Denise McLean & Liaque Latif 14 n Roger Dainty remembered Ken Bromfield 16 n Technicians: the oracles of the laboratory? Andy Connelly 17 n Working in a place like nowhere else on earth: CERN Anna Cook 19 n Management of errors in a clinical laboratory Raffaele Conte 22 n Dicon Nance: a technician in form Andy Connelly 25 n Making and using monoclonal antibody probes Sue Marcus 28 n Flow of electro-deoxidized titanium powder Charles Osarinmwian 31 n Gestalt theories applied to science and technology Kevin Fletcher 35 n Drosophila facility Katherine Whitley 38 n Harris Bigg-Wither and the Roburite Explosives Company Alan Gall 42 n Andrew Schally – from technician to Nobel Prize Andy Connelly 52 n Building your own Raspberry Pi microscope Tim Self 54 n Titanium production in molten electrolytes Charles Osarinmwian -

HERITAGE TRAIL No. 4 to Celebrate Lancashire Day, 2015 Shevington & District Community Association HERITAGE TRAIL NO

Shevington & District Community Association HERITAGE TRAIL No. 4 To Celebrate Lancashire Day, 2015 Shevington & District Community Association HERITAGE TRAIL NO. 4 Welcome to Shevington & District Heritage Trail No. 4 which covers aspects of our local heritage to be found on both sides of Miles Lane from its junction with Broad o’th’ Lane, across the M6 Motorway and up to its Back Lane junction in Shevington Vale. As I have stated in previous trails, I trust this one will also help to stimulate interest in the heritage of our local community and encourage residents to explore it in more detail John O’Neill Introduction Much of the manor of Shevington from earliest recorded times remained a sparsely populated area whose ownership was largely in the shared possession of prominent landed families. As late as Tudor times there were as few as 21 families across the entire area, only 69 by the reign of George III and less than 1,000 inhabitants by the time of Queen Victoria’s accession in 1837. It was still under 2,000 at the 1931 census. The most significant rise occurred between 1951 when it reached 3,057 and up to 8,001 by 1971. At the last Census in 2011 the population had risen to 10,247. Even today, just beyond the current building-line, it can clearly be observed from the M6 motorway, Shevington’s rural landscape of open countryside, woods, streams and ponds remains to a large extent as it was, prior to the short-term local effects of industrial activity from the mid-18th century to the 1950s/60s together with local farming, although the latter is less evident today with the diminution of grazing flocks and herds, than it once was only fifty years ago. -

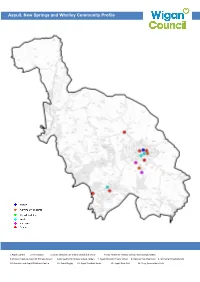

Aspull, New Springs and Whelley Community Profile

Aspull, New Springs and Whelley Community Profile 1.Aspull Library 2.The Surgery 3.Canon Sharples CE Primary School & Nursery 4.Holy Family RC Primary School, New Springs, Wigan 5.St David Haigh & Aspull CE Primary School 6.Our Lady's RC Primary School, Wigan 7. Aspull Church Primary School 8. New Springs Pharmacy 9. WA Salter (Chemists) Ltd 10. Standish and Aspull Childrens Centre 11. Aspull Rugby 12. Aspull Football Junior 13. Aspull Civic Hall 14. Truly Scrumptious Café Aspull, New Springs and Whelley Community Profile Overview of the area Aspull, New Springs and Whelley have a combined resident population of 12,259 which represents 3.8% of the total Wigan resident population of 319,700. Aspull, New Springs & Whelley have a slightly older demographic with 20.3% of all residents aged 65+, above the borough average of 17.6% 11.5% of households are aged 65+ and live alone compared with 11.7% of the borough households. Aspull, New Springs and Whelley has a mix of affluent and deprived communities. Areas such as Chorley Road rank within the top 20% most affluent in England, whilst the areas of Haigh, Whelley and Lincoln Drive are neither affluent nor deprived falling within the 50-60% banding within the Indices of Multiple Deprivation. Holly Road Estate ranks within the top 30% most deprived 11.8% of residents claim out of work benefits, below the borough average of 15.9%. The community is relatively healthy with 6.9% of residents describing their health as ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ compared with the borough average of 7.1%. -

1881 Census Index .For Lancashire for the Name

1881 CENSUS INDEX .FOR LANCASHIRE FOR THE NAME COMPILED BY THE INTERNATIONAL MOLYNEUX FAMILY ASSOCIATION COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved by the International Molyneux Family Association (IMFA). Permission is hereby granted to members to reproduce for genealogical libraries and societies as donations. Permission is also hereby granted to the Family History Library at 35 NW Temple Street, Salt Lake City, Utah to film this publication. No person or persons shall reproduce this publication for monetary gain. FAMILY REPRESENTATIVES: United Kingdom: IMFA Editor and President - Mrs. Betty Mx Brown 18 Sinclair Avenue, Prescot, Merseyside, L35 7LN Australia: Th1FA, Luke Molyneux, "Whitegates", Dooen RMB 4203, Horsham, Victoria 3401 Canada: IMFA, Marie Mullenneix Spearman, P.O. Box 10306, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110 New Zealand: IMFA, Miss Nulma Turner, 43B Rita Street, Mount Maunganui, 3002 South Africa: IMFA, Ms. Adrienne D. Molyneux, P.O. Box 1700, Pingowrie 2123, RSA United States: IMFA, Marie Mullenneix Spearman, P.O. Box 10306, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110 -i- PAGE INDEX FOR THE NAME MOLYNEUX AND ITS VARIOUS SPELLINGS COMPILED FROM 1881 CENSUS INDEX FOR LANCASHIRE This Index has been compiled as a directive to those researching the name MOLYNEUX and its derivations. The variety of spellings has been taken as recorded by the enumerators at the time of the census. Remember, the present day spelling of the name Molyneux which you may be researching may not necessarily match that which was recorded in 1881. No responsibility wiJI be taken for any errors or omi ssions in the compilation of this Index and it is to be used as a qui de only. -

Consecrated & Unconsecrated Parts From

CONSECRATED & UNCONSECRATED PARTS FROM 1920 TO 1929 NAME DATE AGE RANK ADDRESS MODE OF FOLIO ENTRY SECTION GRAVE CLASS CONSECRATED SECTION BURIAL NUMBER NUMBER NUMBER UNCONSECRATED SECTION ILEGIBLE ENTRIES ?? Rose, Stillborn Male & female 19 January 1929 - - Daustone? Sandown Lane Wavertree Public 2134 42648 L 266 352 CEM 9/2/8 Unconsecrated Section ??? Daisy,Daisy, Stillborn Child of 20 December 1923 -- Toxteth Institution Toxteth Park Public 2066 41295 L 272 352 CEM 9/2/7 Unconsecrated Section ??? Jessie Ann 14 January 1922 68 years Widow 114 Claremont Road Wavertree Subsequent 2038 40738 O 480 352 CEM 9/2/7 Unconsecrated Section ??? Mrs, Stillborn Child Of 1 December 1921 - - 116 Rosebery Street Toxteth Park Public 2036 40698 L 274 352 CEM 9/2/7 Unconsecrated Section ??? Mrs, Stillborn Child Of 26 August 1922 - - 50 Jermyn Street Toxteth Park Public 2049 40947 L 273 352 CEM 9/2/7 Unconsecrated Section ????, Mrs, Stillborn Child Of 6 April 1921 - - 50 Jermyn Street Toxteth Park Public 2028 40525 L 275 352 CEM 9/2/7 Unconsecrated Section ???Bottom line missing from front page - Clevedon Street Toxteth Park Subsequent 5864 116941 D Left 523 352 CEM 9/1/23 Consecrated Section ???Jones, David Alexander 24 March 1923 65 years - 88 Claremont Road Wavertree Subsequent 2057 41120 M ? 352 CEM 9/2/7 Unconsecrated Section ???Jones, John Griffith 4 February 1926 69 years - Criccieth Subsequent 2095 41865 E 63 352 CEM 9/2/8 Unconsecrated Section ???White???White, Cl Claraara 20 DDecember b 1922 66 years - 35 EEssex Street St t Toxteth T t th Park -

Travel Vouchers Service Guide for Wigan

Travel Vouchers Service Guide for Wigan 2021 – 2022 tfgm.com Wigan Operators who can carry people in their wheelchairs Remember to say that you will be travelling in your wheelchair when you book your journey and that you will be paying by travel voucher. Bluestar 01942 242 424 Wigan area 01942 515 151 Ring and text back services available Mobile App Buzz 2 Go Minibuses Ltd 01942 355 980 – Wigan 07903 497 456 Wheelchair access Text service available Mobile App C L K Transport Solutions Ltd 07754 259 276 – Wigan 07850 691 579 Text service available JR’s @ Avacabs 01942 681 168 Wigan, Hindley, Ince, Leigh, Culcheth, Astley, 01942 671 461 Golborne, Lowton, Tyldesley, Atherton Wheelchair-accessible vehicles available Travel Vouchers – Wigan 3 Wigan Wigan Operators who can carry people in their wheelchairs Operators who can carry a folded wheelchair (continued) Granville Halsall 07765 408 324 A 2 B Taxis 01942 202 122 Wigan area Bryn, Ashton, Wigan 01942 721 833 Pemberton Private Hire 01942 222 111 – ATC Private Hire 07745 911 539 Wigan and surrounding area 01942 222 204 Ashton-in-Makerfield Wheelchair vehicles available 01942 216 081 Ring back service available Britania Taxis 01942 711 441 Ashton-in-Makerfield Supacabs 01942 881 188 Text back service Atherton, Astley, Hindley Green, Leigh, Tyldesley 01924 884 444 Advanced booking is essential 01942 884 444 Call the Car Ltd 01942 603 888 01942 884 488 Wigan, Leigh 01942 888 111 Minibuses available Travel Time 24/7 private hire Ltd 01257 472 356 Ring and text back services available Mobile -

The London Gazette, Sth November 1993 17881

THE LONDON GAZETTE, STH NOVEMBER 1993 17881 Names, addresses and descriptions of Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death Persons to whom notices of claims are Date before which notices of claims (Surname first) of Deceased to be given and names, in parentheses, to be given of Personal Representatives PICKETT, May Gladys Tegfield House, 24 Chilbolton Avenue, Gibbons & Lunt, 43 Southgate Street, 9th January 1994 (027) Winchester, Hampshire. Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9EH. 9th August 1993. (Pamela Mary Jenkins and Sylvia Jean Grant.) BARNES, Marjorie Joyce G1S Elizabeth Court, Grove Road, Druitts, Borough Chambers, Fir Vale 13th January 1994 (028) Bouremouth, Dorset. Widow. Road, Bournemouth, Dorset BH1 29th July 1993. 2JE. (Colin Alan Barnes and Malcolm Ronald Barnes.) KEMBLE, Harrington 325 Columbia Road, Ensbury Park, Derek T. Wilkinson & Co., 4 Durley 9th January 1994 (029) Talbot Bournemouth, Dorset. Stage Chine Road, Bournemouth BH2 Manager (Retired). SQT, Dorset. (David Paul Comely.) VINCENT, Frank Harold The Regency Rest Home, 119 Meyrick Derek T. Wilkinson &Co., 4 Durley 9th January 1994 (030) Park Crescent, Bournemouth. Car Chine Road, Bournemouth Inspector (Retired). BH2 SQT. Solicitor. (Neil John Vincent). RUFFELL.JohnRuffell 10 Lincoln Road, Parkstone, Poole, Lester Aldridge, 191 Ashley Road, 15th January 1994 (031) Dorset. Van Driver (Retired). Parkstone, Poole, Dorset BH149DP. 18th July 1993. (Ref. ASH.) (Alexander Stronach- Hardy.) MARTIN, Walter William Quaker House, 40 Barton Court Road, Walker Harris & Company, 14th January 1994 (032) Alfred New Milton, Hampshire. Railway 140 Station Road, New Milton, Station Master (Retired). Hampshire. (Anthony John Harris 30th October 1993. and Peter Oliver Bromfield.) WOODCOCK, Clarice 23 Femside Road, West Moors, Coles Miller, 141 Station Road, West 9th January 1994 (033) Mary Dorset. -

52 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

52 bus time schedule & line map 52 Trafford Centre - Failsworth Via Eccles, Salford View In Website Mode Shopping Ctr, Cheetham Hill The 52 bus line (Trafford Centre - Failsworth Via Eccles, Salford Shopping Ctr, Cheetham Hill) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Cheetham Hill: 6:10 AM - 11:50 PM (2) Eccles: 4:45 AM - 6:25 PM (3) Failsworth: 5:20 AM - 9:25 PM (4) Higher Crumpsall: 6:55 PM (5) Pendleton: 6:22 PM - 10:52 PM (6) The Trafford Centre: 6:05 AM - 8:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 52 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 52 bus arriving. -

The Rise of Bolton As an Important Engineering and Textile Town in Early 1800 England

I. međunarodna konferencija u povodu 150. obljetnice tvornice torpeda u Rijeci i očuvanja riječke industrijske baštine 57 THE RISE OF BOLTON AS AN IMPORTANT ENGINEERING AND TEXTILE TOWN IN EARLY 1800 ENGLAND Denis O’Connor, Industrial Historian Bolton Lancashire, Great Britain INTRODUCTION The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that Great Britain changed, in the 19th Century, from a rural economy to one based on coal and iron. In doing so it created conditions for British civil, textile and mechanical engineers, such as Robert Whitehead of Bolton, to rise to positions of eminence in their particular fields. Such men travelled across Europe, and laid, through the steam engine and railways, the foundations for many of the regions present day industries. EARLY TEXTILES AND BLEACHING. RISE OF LOCAI INDUSTRIES The origins of Bolton’s textile and engineering industry lie back in the 12th Century with the appointment of a Crown Quality Controller called an Ulnager. During the reign of Henry V111 an itinerant historian Leland observed that ‘Bolton - upon - Moore Market standeth by the cotton and coarse yarns - Diverse villages above Bolton do make Cotton’ and that ‘They burne at Bolton some canelle (coal) of which the Pitts be not far off’. Coal, combined with the many powerful streams of water from the moorlands, provided the basic elements for the textile industry to grow, the damp atmosphere conducive to good spinning of thread. In 1772 a Directory of Manchester (10-12 miles distant) was published, in this can be seen the extent of cloth making in an area of about 12 miles radius round Manchester, with 77 fustian makers (Flax warp and cotton or wool weft) attending the markets, 23 of whom were resident in Bolton. -

Past Forward 31

ISSUE No. 31 SUMMER 2002 The Newsletter of Wigan Heritage Service FREE From the Editor EUROPE IN FOCUS WELCOME to the summer edition of Past Forward. As always, you will find a splendid mix of articles Angers 2002 by contributors old and new. These are exciting times for the Heritage Service, which has ANGERS is twinned with will be loaned to Angers for the enjoyed an international profile of Wigan, and indeed with a exhibition. Local firms Millikens late - worldwide publicity followed number of other towns, and William Santus, as well as Alan Davies’s feature in the last including Osnabruck, Pisa, Wigan Rugby League Club, have issue of the recently discovered Haarleem and Seville. During also made contributions to treasure Woman’s Worth (see p3), September, the French town will Wigan’s part of the exhibition. while the History Shop was featured in the final episode of be mounting a major exhibition, Wigan Pier Theatre Company Simon Shama’s History of Britain, ‘Europe in Focus’, which will will also be taking part, as will shown in June. And the Service feature displays and John Harrison, a young flautist has played a key role in Wigan’s contributions from all its from Winstanley College, Wigan. contribution to a major exhibition in twinned towns. I will ensure that a plentiful Angers, its twin town, in Wigan Heritage Service has supply of Past Forward will be September (see right). played a leading role in Wigan’s available - a good opportunity to Nearer to home, I am delighted with the progress which is being contribution, and a selection of expand the readership on the made by the Friends of Wigan museum artefacts and archives continent! Heritage Service, with lots of exciting projects in the pipeline. -

North West River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 PART B – Sub Areas in the North West River Basin District

North West river basin district Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 PART B – Sub Areas in the North West river basin district March 2016 1 of 139 Published by: Environment Agency Further copies of this report are available Horizon house, Deanery Road, from our publications catalogue: Bristol BS1 5AH www.gov.uk/government/publications Email: [email protected] or our National Customer Contact Centre: www.gov.uk/environment-agency T: 03708 506506 Email: [email protected]. © Environment Agency 2016 All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. 2 of 139 Contents Glossary and abbreviations ......................................................................................................... 5 The layout of this document ........................................................................................................ 8 1 Sub-areas in the North West River Basin District ......................................................... 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 10 Management Catchments ...................................................................................................... 11 Flood Risk Areas ................................................................................................................... 11 2 Conclusions and measures to manage risk for the Flood Risk Areas in the North West River Basin District ...............................................................................................