TOCAPE R:Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upendra (Actor) Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Upendra (actor) 电影 串行 (大全) S/O Satyamurthy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/s%2Fo-satyamurthy-16254994/actors Kanyadanam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kanyadanam-16250143/actors Hollywood https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hollywood-15048661/actors Uppi Dada M.B.B.S. https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/uppi-dada-m.b.b.s.-7899084/actors Preethse https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/preethse-7239771/actors Super Star https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/super-star-7642802/actors Naanu Naane https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/naanu-naane-16252037/actors Mukunda Murari https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mukunda-murari-26963162/actors Superro Ranga https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/superro-ranga-17082037/actors Anatharu https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/anatharu-4752039/actors Rajani https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rajani-28180133/actors Dubai Babu https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dubai-babu-5310505/actors Kutumba https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kutumba-6448652/actors Gowramma https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gowramma-5590114/actors Gokarna https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gokarna-5578039/actors Omkara https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/omkara-7090236/actors Raa https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/raa-7278365/actors Auto Shankar https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/auto-shankar-4826123/actors Arakshaka https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/arakshaka-4783859/actors News https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/news-16957621/actors -

RCF Fellows Kai He.Ai

Decision Making During Crises: Prospect Theory and China’s Foreign Policy Crisis Behavior after the Cold War Kai He Utah State University May 2012 EAI Fellows Program Working Paper Series No. 33 Knowledge-Net for a Better World The East Asia Institute(EAI) is a nonprofit and independent research organization in Korea, founded in May 2002. The EAI strives to transform East Asia into a society of nations based on liberal democracy, market economy, open society, and peace. The EAI takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors. is a registered trademark. Copyright © 2012 by EAI This electronic publication of EAI intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Copies may not be duplicated for commercial purposes. Unauthorized posting of EAI documents to a non-EAI website is prohibited. EAI documents are protected under copyright law. The East Asia Institute 909 Sampoong B/D, 310-68 Euljiro 4-ga Jung-gu, Seoul 100-786 Republic of Korea Tel. 82 2 2277 1683 Fax 82 2 2277 1684 EAI Fellows Program Working Paper No. 33 Decision Making During Crises: Prospect Theory and China’s Foreign Policy Crisis Behavior after the Cold War* Kai He Utah State University May 2012 Abstract Through examining four notable foreign policy crises with the United States since the end of the Cold War: the 1993 Yinhe ship inspection incident, the 1995-6 Taiwan Strait crisis, the 1999 embassy bombing incident, and the 2001 EP-3 midair collision, I introduce a prospect theory- based model to systematically explain China’s foreign policy crisis behavior after the cold war. -

JAN to APRIL.Xlsx

List of feature films certified from 01 Jan 2021 to 30 April 2021 Certified Type Of Film Application Production Certificate Sr. No. Title Language Certificate No. Certificate Date Duration/Le (Video/Digita Producer Name Date House Type ngth l/Celluloid) Assamese ASSAMESE WITH R.C. FILMS 1 COMMANDO 23-02-2021 DIL/1/3/2021-GUW 02 March 2021 87.18 Digital Rekha Chamuah U PARTLY HINDI PRODUCTION 2 DEUTA 27-04-2021 Assamese DIL/1/8/2021-GUW 29 April 2021 82.54 Digital Dishan Dholua - U AWADHI GOLDMINES ULKA MANISH 1 SAKTHI 23-12-2020 AWADHI VIL/2/2/2021-DEL 13 January 2021 138.15 Video TELEFILMS PVT UA SHAH LTD GOLDMINES ULKA MANISH 2 REBEL 22-01-2021 AWADHI VIL/2/6/2021-DEL 04 February 2021 143.57 Video TELEFILMS PVT UA SHAH LTD UPPALAPATI VENKATA 3 MIRCHI 01-02-2021 AWADHI VIL/2/7/2021-DEL 12 February 2021 137.51 Video U V CREATIONS UA SATYANARAYA NARAJU GOLDMINES ULKA MANISH 4 POWER 18-02-2021 Awadhi VIL/2/10/2021-DEL 26 February 2021 126.46 Video TELEFILMS PVT UA SHAH LTD NALLAMALUPU LAKSHMI POWER RETURNS ( 5 13-03-2021 AWADHI VIL/2/11/2021-DEL 19 March 2021 143.21 Video SRINIVASREDD NARASIMHA UA RACE GURRAM ) Y PRODUCTIONS Sumeet Kishen 6 AMBARISHA 16-03-2021 AWADHI VIL/2/81/2021-MUM 26 March 2021 135.44 Video SUMEET ARTS UA Saigal GOLDMINES ULKA MANISH 7 VETTAIKAARAN 25-03-2021 Awadhi VIL/2/18/2021-CUT 07 April 2021 150.33 Video TELEFILMS PVT UA SHAH LTD GOLDMINES ULKA MANISH 8 DHRUVA 03-04-2021 Awadhi VIL/2/97/2021-MUM 09 April 2021 150.5 Video TELEFILMS PVT UA SHAH LTD Bengali WELCOME INDIA TO Prantosh 1 12-12-2020 Bengali DIL/1/1/2021-KOL -

United States House Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations

United States House Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the 1952-1954 investigation into non-profits. For the 80s and 90s report on the People's Republic of China's covert operations within the United States, see Cox Report. The Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives between 1952 and 1954.[1] The committee was originally created by House Resolution 561 during the 82nd Congress. The committee investigated the use of funds by tax-exempt organizations (non-profit organizations) to see if they were being used to support communism.[2][3] The committee was alternatively known as the Cox Committee and the Reece Committee after its two chairmen, Edward E. Cox and B. Carroll Reece. Contents • 1 History • 2 Members • 3 Dodd report • 4 Final report • 5 Criticisms • 6 References History In April 1952, the Select Committee to Investigate Tax-Exempt Foundations and Comparable Organizations (or just the Cox Committee Investigation), led by Edward E. Cox, of the House of Representatives began an investigation of the "educational and philanthropic foundations and other comparable organizations which are exempt from federal taxes to determine whether they were using their resources for the purposes for which they were established, and especially to determine which such foundations and organizations are using their resources for un-American activities and subversive activities or for purposes not in the interest or tradition of the United States." In the fall of 1952 all foundations with assets of $10 million or more received a questionnaire covering virtually every aspect of their operations. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1956PLC010806 Prefill Company/Bank Name CLARIANT CHEMICALS (INDIA) LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3803100.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) THOLUR P O PARAPPUR DIST CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J DANIEL AJJOHN INDIA Kerala 680552 5932.50 02-Oct-2019 TRICHUR KERALA TRICHUR 3572 unpaid dividend INDAS SECURITIES LIMITED 101 CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J SEBASTIAN AVJOSEPH PIONEER TOWERS MARINE DRIVE INDIA Kerala 682031 192.50 02-Oct-2019 3813 unpaid dividend COCHIN ERNAKULAM RAMACHANDRA 23/10 GANGADHARA CHETTY CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A K ACCHANNA INDIA Karnataka 560042 3500.00 02-Oct-2019 PRABHU -

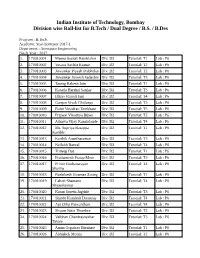

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Division Wise Roll-List for B.Tech / Dual Degree / B.S

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Division wise Roll-list for B.Tech / Dual Degree / B.S. / B.Des Program : B.Tech. Academic Year-Semester 2017-1 Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2017 1. 170010001 Meena Sourav Ramkishor Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P6 2. 170010002 Vasava Sachin Kumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P6 3. 170010003 Jirwankar Piyush Prabhakar Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P6 4. 170010004 Jirwankar Saieesh Sadashiv Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P6 5. 170010005 Tarang Rakesh Jain Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P6 6. 170010006 Kataria Harshal Sanjay Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P6 7. 170010007 Dhruv Rajesh Jain Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P6 8. 170010008 Gunjan Vivek Chitlange Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P6 9. 170010009 Rohit Vinodrao Tembhare Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P6 10. 170010010 Prajwal Vinodrao Bijwe Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P6 11. 170010011 Atharva Vijay Kanakdande Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P6 12. 170010012 Ms. Supriya Basappa Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P6 Kamble 13. 170010013 Karthik Anantharaman Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P6 14. 170010014 Neilabh Banzal Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P6 15. 170010015 Trideep Das Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P6 16. 170010016 Prathamesh Pratap More Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P6 17. 170010017 Prince Rudranarayan Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P6 Sharma 18. 170010018 Rushikesh Hiraman Zoting Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P6 19. 170010019 Lahoti Shantanu Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P6 Shyamkumar 20. 170010020 Karan Suresh Jagdale Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P6 21. 170010021 Shinde Kamlesh Dattatray Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P6 22. -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S

Order Code RL30143 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Secrets Updated February 1, 2006 Shirley A. Kan Specialist in National Security Policy Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Secrets Summary This CRS Report discusses China’s suspected acquisition of U.S. nuclear weapon secrets, including that on the W88, the newest U.S. nuclear warhead. This serious controversy became public in early 1999 and raised policy issues about whether U.S. security was further threatened by China’s suspected use of U.S. nuclear weapon secrets in its development of nuclear forces, as well as whether the Administration’s response to the security problems was effective or mishandled and whether it fairly used or abused its investigative and prosecuting authority. The Clinton Administration acknowledged that improved security was needed at the weapons labs but said that it took actions in response to indications in 1995 that China may have obtained U.S. nuclear weapon secrets. Critics in Congress and elsewhere argued that the Administration was slow to respond to security concerns, mishandled the too narrow investigation, downplayed information potentially unfavorable to China and the labs, and failed to notify Congress fully. On April 7, 1999, President Clinton gave his assurance that partly “because of our engagement, China has, at best, only marginally increased its deployed nuclear threat in the last 15 years” and that the strategic balance with China “remains overwhelmingly in our favor.” On April 21, 1999, Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) George Tenet, reported the Intelligence Community’s damage assessment. -

MANALI PETROCHEMICALS LIMITED CIN : L24294TN1986PLC013087 Regd Off: 'SPIC HOUSE', 88, Mount Road, Guindy, Chennai- 600 032

MANALI PETROCHEMICALS LIMITED CIN : L24294TN1986PLC013087 Regd Off: 'SPIC HOUSE', 88, Mount Road, Guindy, Chennai- 600 032. Tele-Fax No.: 044-22351098 Email: [email protected], Website: www.manalipetro.com DETAILS OF SHARES TO BE TRANSFERRED TO INVESTOR EDUCATION & PROTECTION FUND ON WHICH NO DIVIDEND HAS BEEN CLAIMED FOR THE FY 2008-09 TO 2015-16 SL.NO FOLIO_DP_ID_CL_ID NAME OF THE SHAREHOLDER NO.OF.SHARES TOBE TRFD TO IEPF 1 A0000033 SITARAMAN G 450 2 A0000089 LAKSHMANAN CHELLADURAI 300 3 A0000093 MANI N V S 150 4 A0000101 KUNNATH NARAYANAN SUBRAMANIAN 300 5 A0000120 GOPAL THACHAT MURALIDHAR 300 6 A0000130 ROY FESTUS 150 7 A0000140 SATHYAMURTHY N 300 8 A0000142 MOHAN RAO V 150 9 A0000170 MURALIDHARAN M R 300 10 A0000171 CHANDRASEKAR V 150 11 A0000187 VISWANATH J 300 12 A0000191 JAGMOHAN SINGH BIST 300 13 A0000213 MURUGANANDAN RAMACHANDRAN 150 14 A0000219 SHANMUGAM E 600 15 A0000232 VENKATRAMAN N 150 16 A0000235 KHADER HUSSAINY S M 150 17 A0000325 PARAMJEET SINGH BINDRA 300 18 A0000332 SELVARAJU G 300 19 A0000334 RAJA VAIDYANATHAN R 300 20 A0000339 PONNUSWAMY SAMPANGIRAM 300 21 A0000356 GANESH MAHADHEVAN 150 22 A0000381 MEENAKSHI SUNDARAM K 150 23 A0000389 CHINNIAH A 150 24 A0000392 PERUMAL K 300 25 A0000423 CHANDRASEKARAN C 300 26 A0000450 RAMAMOORTHY NAIDU MADUPURI 150 27 A0000473 ZULFIKAR ALI SULTAN MOHAMMAD 300 28 A0000550 SRINIVASAN K 150 29 A0000556 KANAKAMUTHU A 300 30 A0000561 KODANDA PANI CHIVUKULA 300 31 A0000565 VARADHAN R 150 32 A0000566 KARTHIGEYAN S 150 33 A0000598 RAMASASTRULU TRIPIRNENI 150 34 A0000620 -

Brown Cowboys on Film: Race, Heteronormativity and Settler Colonialism

BROWN COWBOYS ON FILM: RACE, HETERONORMATIVITY AND SETTLER COLONIALISM BEENASH JAFRI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GENDER, FEMINIST & WOMEN’S STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO JULY 2014 © Beenash Jafri, 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes minority-produced westerns as examples of settler cinemas. Though they are produced by subjects at the margins of settler society, I argue that settler colonialism is, nonetheless, a significant cultural context shaping these films. The dissertation intervenes into existing film studies scholarship, which has tended to frame settler colonialism as the historical context structuring the racial oppression of Native Americans, rather than as a constitutive feature of all forms of racial subjugation. As a result, the connections and investments of other racialized subjects within the dynamics of settler colonialism have received limited attention. Drawing on queer, race and Native American/Indigenous studies, the dissertation develops and deploys an intersectional framework for examining film that illuminates the fraught relationship between racialized minorities, Indigenous peoples and settler colonialism. To make its argument, the dissertation examines three sets of films: black westerns, South Asian diaspora films, and Jackie Chan’s martial arts westerns. In each chapter, I consider how existing film scholarship has read these respective films before offering an alternative interpretation that draws attention to their settler colonial contexts. For example, black westerns have been interpreted in terms of anti-racist historical revisionism; South Asian diasporic films have been analyzed in terms of their liminal position between Hollywood and Bollywood film industries; and Jackie Chan’s western parodies have been interpreted in terms of postmodern mimicry. -

List of Digital Theatres for UFO Movies India Ltd

List of Digital Theatres For UFO Movies India Ltd. S.No. THEATRE_CODE THEATRE_NAME ADDRESS1 CITY ACTIVE PAYEE_CODE DISTRICT STATE COMPANY_NAME CMP_CODE SEATING INS_DATE WEB_CODE Main Road, Tagarapuvalasa, Ganesh 1 TH1177 Vizaq, Pin - 531162, Andhra Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 537 9/26/2011 3235 (Tagarapuvalasa) Pradesh Bowdava Road, Vizag, Pin - 2 TH1178 Gokul Visakhapatnam Y 1 Visakhapatnam ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 515 9/26/2011 3244 530004, Andhra Pradesh Main Road, Parvathipuram, Sri Veerabhadra 3 TH1180 Dist-Vijayanagaram, Pin Parvathipuram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 396 9/26/2011 3698 Picture Palace Code - 535501 AP Radhamadhav Chipurupalli, 4 TH1181 Theatre Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 517 9/26/2011 3717 Vijayanagaram (Chipurupalli) 5 TH1182 N.C.S. Theatre A/C Vizianagaram, Pin - 535001 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 577 9/26/2011 2696 Sri Vasavi Kala Main Road, Bobbili, 6 TH1183 Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 475 9/26/2011 2700 Mandir (Bobbili) Vizianagaram, Sri Ramanaah 7 TH1184 Theatre Devarapalli, West Godavari Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 371 9/26/2011 2689 (Devarapalli) Main Road, Moidha Sri Satya Theatre 8 TH1185 Junction, Nellimarla, Vizianagaram Y 1 Vizianagaram ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 258 9/26/2011 2588 (Nellimarla) Vizianagaram, Pin - 535217 LakshmiLakshmi KKrishnarishna 9 TH1186 Janagoan, Warangal, AP Janagoan Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 747 9/26/2011 832 Deluxe Sri Venkateshwara Main Road, Maripeda - 10 TH1187 Maripeda Y 1 Warangal ANDHRA PRADESH UFO 1 459 9/26/2011 2653 Theatre 506315, Dist Warangal Main RoadRoad,, MariMaripeda,peda, Dist.-Dist. -

Cox Committee's Report

Order Code RL30220 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China’s Technology Acquisitions: Cox Committee’s Report — Findings, Issues, and Recommendations June 8, 1999 (name redacted) Specialist in National Security Policy Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress ABSTRACT On May 25, 1999, the House Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People’s Republic of China (Cox Committee) released the declassified version of its January 3, 1999 classified report on its investigation of U.S. technology transfers to China. The 3-volume, 871-page unclassified report discussed findings related to Chinese acquisition of U.S. nuclear weapon information, missile technology through satellite exports, high-performance computers, and other dual-use technology. The report made 38 recommendations. This CRS report summarizes the major findings of the Cox Committee’s unclassified report, discusses some issues for further study, and summarizes the committee’s recommendations. This CRS report will not be updated. (See also: CRS Report 98-485, China: Possible Missile Technology Transfers from U.S. Satellite Export Policy — Background and Chronology; CRS Report RL30143, China: Suspected Acquisition of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Data; and CRS Report RL30231, Technology Transfer to China: an Overview of the Cox Committee Investigation Regarding Satellites, Computers, and DOE Laboratory Management.) China’s Technology Acquisitions: Cox Committee’s Report — Findings, Issues, and Recommendations Summary The House approved H.Res. 463 on June 18, 1998, to create the Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People’s Republic of China (PRC).