Psychogeographic Excursions: Mapping Calgary’S Contemporary Theatre Scene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olympic Plaza Cultural District Engagement & Design Report

Olympic Plaza Cultural District Engagement & Design Report October 2016 Contents A New Future for the Olympic Plaza Cultural District Detailed What We Heard Results 1 page 1 A page 51 Community Engagement : What We Heard Public Engagement Materials 2 page 7 B page 61 Engagement Activities 9 Verbatim Comments Key Themes 11 C page 69 Olympic Plaza Cultural District Challenge Questions 3 page 14 honour the Olympic legacy and heritage of the space while recognizing the current (and future) reality of Calgary? 17 how activate the Olympic Plaza Cultural District in a way that facilitates both structured and organic happenings? 21 balance the green and grey elements of the Olympic Plaza Cultural District? 25 might activate the space in all seasons? 29 celebrate local food and commerce in the space? 33 fully integrate arts and culture into the life of the Olympic Plaza Cultural District? 37 we ... make the Olympic Plaza Cultural District safe and welcoming for all? 41 ensure all Calgarians have access to the Olympic Plaza Cultural District? 45 Next Steps 4 page 50 ii The City of Calgary | Olympic Plaza Cultural District Executive Summary The Olympic Plaza Cultural District is Calgary’s In early 2016, Calgary City Council approved the The Olympic Plaza Cultural District Engagement Civic District Public Realm Strategy. The document & Design Report is the product of this engagement living room. It represents the city’s legacy as identified Olympic Plaza and its surrounding spaces process. The report reintroduces the Olympic Plaza as an important part of the city and prioritized it Cultural District concept – first noted in the Civic an Olympic host yet remains an important for a major review of its design and function. -

GLENBOW RTTC.Pdf

2012–13 Report to the Community REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY 2012–13 Contents 1 Glenbow by the Numbers 2 Message from the President and Chair 4 Exhibitions 6 Events and Programs 8 Collections and Acquisitions 10 Support from the Community 12 Thank You to Our Supporters 14 Volunteers at Glenbow 15 Board of Governors 16 Management and Staff About Us In 1966, the Glenbow-Alberta Institute the Province of Alberta have worked was created when Eric Harvie and his together to preserve this legacy for future family donated his impressive collection generations. We gratefully acknowledge of art, artifacts and historical documents the Province of Alberta for its ongoing to the people of Alberta. We are grateful support to enable us to care for, maintain for their foresight and generosity. In and provide access to the collections the last four decades, Glenbow and on behalf of the people of Alberta. Glenbow Byby the Numbers 01 Library & Archives Operating Fund Operating Fund researchers served Revenue Expenditures 5% 9% 11% 6% 33% 32% 9% 7,700 19% 22% 9% 20% 25% Amortization of Deferred Depreciation & Revenue (Property & Amortization - $919,818 43,072 Equipment) - $493,443 Total in-house and outreach Commercial Library & Archives - $534,838 Activities - $1,032,498 education program participants Commercial Activities Admissions & & Fundraising - $1,891,010 Memberships - $859,785 Collections Miles that artwork for the Fundraising- $2,068,248 Management - $923,889 Programs & Exhibition Charlie Russell exhibition travelled Investment Development - $2,422,362 Income - $1,849,922 Government Central Services - $3,184,154 of Alberta - $3,176,000 Audited fi nancial statements for the year ended March 31, 2013 8,000 can be found at www.glenbow.org 108 Rubbermaid totes 117,681 used in Iain BAAXTERXTER&’s installation Shelf Life Total Attendance Number of artifacts and 797 works of art treated by Charlie Russell Glenbow conservation staff exhibition catalogues sold in the Glenbow Museum Shop 220 02 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY 2012–13 Message from the Donna Livingstone R. -

CALL for SUBMISSIONS +15 SOUNDSCAPE 2019-2020 Season

CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS +15 SOUNDSCAPE 2019-2020 Season DEADLINE FOR PROPOSAL: Monday, January 14 2019. Email submission to: Natasha Jensen, Visual and Media Arts Specialist [email protected] Attention: +15 Soundscape Submission +15 Walkway: The +15 walkway is a high traffic pedestrian walkway (essentially an indoor sidewalk) and Arts Commons +15 is connected to City Hall on the east and Glenbow Museum on the west via the +15 walkway system - a series of 57 enclosed bridges at approximately 15 feet above street level that connect a majority of the buildings in the Calgary downtown core. Please note that the +15 system closes at midnight each night. Description of +15 Soundscape: The +15 Soundscape is a multi-channel speaker system located on the +15 level of Arts Commons (205 8th Ave SE) that provides highly unique sound art opportunities to local and national sound artists. The +15 Soundscape is one of the few systems like it in the world, where experimental sound art, sonic art, compositions, electronic-art, radio plays, etc are presented. The +15 Soundscape provides a unique opportunity to engage with a diverse audience, including the local artistic community of Calgary, Alberta. Arts Commons receives over 600,000 patrons a year and the +15 walkway is used by thousands of pedestrians daily. The broad audience include: cultural workers, commuters, teachers, children, vulnerable populations, city officials, artists, and others. Selected Soundscape piece: The selected piece must be a minimum of 60 minutes in length and will loop continuously for three to four months. The proposal must include a 10-15 minute sample of your proposed soundscape. -

Tothecomm N 2014-15 • � R■Tl!,Itt, V■ 1111 Art.., (Uinrnqni � %Ili

totheComm n 2014-15 • r■tl!,Itt, V■ 1111 Art.., (uInrnQni %Ili. Es e •g:Taylt'a Esmsery. OUR VISION: A creative and compassionate society, inspired through the arts. OUR MISSION: To bring the arts... to life What's in a name? Arts Commons "Arts" Includes all forms of creative human expression. "Commons" Derived from the old town square concept where ideas are shared, people from all walks of life gather, and different perspectives are welcomed. „Welcome to you ‘066.4 Left page: Ltin Lava st,. pa rl ol the RIM' World :4,11Nie Serie, k Contert HP Iridud Loa. Right page (Ctinekwise ream top-left): 1.10 rol pr 1 rc' l'J An; Art, C. trtor nt ttO. 11 ( ■• rit111. , 0% Ck•ttl r CI. I 1 TO1 hoI1 1Lr A.: k U, q1e1.1 I 11.111 1101 injn,Iiu, • Tarlt;■ Konnere How did we get here? ;l> ;0 -I n'" o 3: 3: o z n spring of 2014, we entered into a rebranding exercise in response to the need to replace the outdated '"N EPCOR ICENTRE name, modernize our public-facing brand, and reshape perceptions around our complete ....~ offering. better reflecting our current position today and our goals for the future. It wasn't easy . , I N ~ U1 We started l ur transformation in a very deliberate way over 5 years, including a rev isit of our past and an exploration of what we and our community wanted our future to look like. When it came time to rebrand, we engaged and met with an inclusive group of community members and key stakeholders to refine and determine this organization's role today 6 as a key co 'tributor to the social, economic, cultural, and intellectual life and well-being of Calgarians and visitors alike. -

One Yellow Rabbit Performance Theatre (OYR) Harnesses the Bold, Adventurous Spirit of Our Calgary Community to Enrich the Place We Live

One Yellow Rabbit Performance Theatre Report to the Community 2014/2015 Community the to Report Robust cultural landscapes nurture vibrant societies. Through high-calibre work in the performing arts across the wide range of projects we undertake each season, One Yellow Rabbit Performance Theatre (OYR) harnesses the bold, adventurous spirit of our Calgary community to enrich the place we live. Our mission is to create and present vital, surprising performance experiences that engage and reward our audience. We believe it is through this kind of artistic To realize this vision work – work that arouses curiosity, ignites we are commited to… passion, stimulates imagination and challenges expectation – that individuals 6WhW^ab[`YS`VbdaVgU[`YfZW are inspired and communities fourish. work of the One Yellow Rabbit Performance Ensemble By extension, we believe that the rigor and love that feeds the work we put forward 7VgUSf[`YS`V_W`fad[`Y`Wi translates to a community that values and established artists through connection, compassion, and strives programs like the Summer to nourish its people – a society that is Lab Intensive and the galvanized by challenge and energized by beautifulyoungartists initiative possibility. BdaVgU[`YS`VbdWeW`f[`YfZW High Performance Rodeo, Calgary’s International Festival of the Arts 5W^WTdSf[`YfZWegbbadfaXagd community partners through special events like Wine Stage and unique events in the Big Secret Theatre Our Mission Cover photo credit: Kelly Hofer Kelly credit: photo Cover Photo Credit: Kelly Hofer The work of One Yellow Rabbit Our heartfelt thanks to everyone who has One Yellow Rabbit Performance Theatre is entrenched in helped One Yellow Rabbit throughout Performance Ensemble Staf deeply rooted values of respect, dignity, this year. -

Hounsfield Heights Briar Hill

APRIL 2017 DELIVERED MONTHLY TO 2,000 HOUSEHOLDS your HOUNSFIELD BRIAR A QUIET CENTRAL RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITY WITH FRIENDLY NEIGHBOURS CONNECTED THROUGH ACTIVE PUBLIC SPACES THE OFFICIAL HOUNSFIELD HEIGHTS-BRIAR HILL COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER | www.hh-bh.ca RBC Dominion Securities Inc. CONTENTS Did you know that our newsletters reach 5 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 22% more households than flyer drops? 7 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 9 CANADA’S 150: CALLING ALL SINGERS / LOOKING TO BUILD & RETAIN A PRODUCTIVE, MUSICIANS / ACTORS / DANCERS AND MOTIVATED WORKFORCE? WANNABEES! RBC Group Advantage is a comprehensive program designed to help business owners meet their employees’ financial needs by providing: 9 OUTDOOR SOCCER: REFEREES NEEDED ■■ In-person financial advice for all employees ■■ Group retirement savings plans 10 WEST HILLHURST COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION ■■ Comprehensive and discounted banking solutions Target your audience by specific EARTH DAY Support your employees and keep your competitive advantage. Call community and grow your sales. Investment Advisor Michael Martin at 403-266-9655 to learn more. 12 ABOUT WINE 14 REAL ESTATE UPDATE Call to book your Ad 91 Monthly Community Newsletters Delivered to RBC Dominion Securities Inc.* and Royal Bank of Canada are separate corporate entities which are affiliated. *Member-Canadian 403-263-3044 415,000 Households Across 14 CASINO VOLUNTEERS NEEDED Investor Protection Fund. RBC Dominion Securities Inc. is a member company of RBC Wealth Management, a business segment of Royal Bank of Canada. ®Registered trademarks of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under licence. © RBC Dominion Securities Inc. 2015. [email protected] 152 Calgary Communities All rights reserved. 15_90701_RHD_011 16 FRIENDS OF NOSE HILL 16 MY BABYSITTER LIST 18 AT A GLANCE 9 14 12 16 IMPORTANT NUMBERS PRESIDENT'S ALL EMERGENCY CALLS 911 MESSAGE month, we are beginning to plan a 3000 square foot multi-use addition to our building and would like your Alberta Adolescent Recovery Centre 403-253-5250 Welcome to April everyone! ideas and help. -

Report to the Community 2017-18 Arts Commons 1

. Our Vision: A creative and compassionate society, inspired through the arts. Our Mission: To bring the arts This is YOUR …to life. Arts Commons Crafting paper puppets at Happenings 13 © Will Young Snotty Nose Rez Kids perform at National Indigenous Peoples Day © Elizabeth Cameron Report to the Community 2017-18 Arts Commons 1 Artists from Classic Albums Live speak to members of Founders Circle © Will Young Selci performs at Happenings 13 © Will Young Table of Contents This is YOUR Arts Commons message from the Board PG 2 Our Mandate is… to foster, present, and promote the arts PG 4 to provide and care for our assets PG 6 to ensure optimal access and utilization of our assets PG 8 Arts Commons Presents… creates connections PG 12 inspires learning PG 14 uplifts and energizes PG 17 is for you PG 18 Arts Commons demonstrates sustainability PG 20 thank you PG 22 2 Arts Commons Report to the Community 2017-18 Report to the Community 2017-18 Arts Commons 3 What’s in a year? This year has been another interesting these trying times, and the Calgary The rebranding of the Centre as Arts Commons Presents programming one for Calgary. While we are still seeing International Children’s Festival made the Arts Commons exemplifies the values by adding programs like National some lingering effects, the economic difficult decision to close its doors after and vision that Johann brought to his Geographic Live, and instituting our downturn seems to have finally turned 32 years. tenure – “A creative and compassionate growing volunteer Concierge program upwards. -

Civic Partner 2019 Annual Report Snapshot- Calgary Centre for Performing Arts (Arts Commons) C P S 2020 -1051 at T Ac H M En

ISC:UNRESTRICTED CPS2020 CIVIC PARTNER 2019 ANNUAL REPORT SNAPSHOT- CALGARY CENTRE FOR PERFORMING ARTS (ARTS COMMONS) - CALGARY CENTRE FOR PERFORMING ARTS (ARTS COMMONS) 2019 City Investment 1051 Attachment Mission: To bring the arts...to life. Operating Grant:$2,479,738 Mandate: To foster, present and promote the arts; to provide and care for our assets; to ensure optimal Capital Grant:$1,555,993 utilization of our assets. Registered Charity City owned asset? Yes One Calgary Line of Service: Economic Development and Tourism 1 7 2019 Results Use of Venue Students Engaged in Arts Education Number of Community Organizations Programs Using Venues 2000 12,000 10,665 250 10,158 10,229 200 1500 10,000 175 179 1,609 200 1,510 8,000 1000 1,379 150 6,000 100 500 4,000 2,000 50 0 0 0 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 2017 2018 2019 The story behind the numbers • Arts Commons is a key contributor to the social, economic, cultural, and intellectual life and wellbeing of Calgarians and visitors. • Arts Commons works collaboratively with the Calgary Board of Education and the Calgary Catholic School District to bring high-quality and immersive learning experiences to Calgary students and their teachers. • Arts Commons maintains meaningful relationships with the public and private sectors that support provision of programs and services for the benefit of the community. Current state 2020: COVID-19 impact • All venues closed on March 12, and the full facility closed on March 23. • To support the sustainability of resident companies, Arts Commons waived $487,057 in venue occupancy fees through to August 2020, and continues to work with them to navigate a very uncertain 2020/21 season. -

The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia

The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust August 2004 The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia Report by Lisa O’Shaughnessy 2002/2 Churchill Fellow + 61 417 908 519 email – [email protected] The Peter Mitchell Churchill Fellowship To study and observe overseas international touring Theatre Companies I understand that the Churchill Trust may publish this Report, either in hard copy or on the internet or both, and consent to such publication. I indemnify the Churchill Trust against any loss, cost or damages it may suffer arising out of any claim or proceedings made against the trust in respect of, or arising out of, the publication of any Report submitted to the Trust and which the Trust places on a website for access over the internet. I also warrant that my Final Report is original and does not infringe the copyright of any person, or contain anything which is, or the incorporation of which the final report is, actionable for defamation, a breech of any privacy law or obligation, breach of confidence, contempt of court, passing off or contravention of any other private right or of any law. Signed: Lisa O’Shaughnessy Dated: 20th August 2004 Lisa O’Shaughnessy Page 1 of 13 The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust August 2004 Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia Cover Page Page 1 Index Page Page 2 Introduction Page 3 Acknowledgements Page 4 Executive Summary Page 5 Program Pages 6 and 7 Main Body Pages 8, 9 and 10 Conclusions Pages 10 and 11 Recommendations Pages 12 and 13 Lisa O’Shaughnessy Page 2 of 13 The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust August 2004 Introduction: My passion and preoccupation with the theatre was kindled in my primary school years, as I was blessed with a principal and the drama teacher who took the school on a magical journey of musicals. -

Lloydminster Realtors'

LLOYDMINSTER REALTORS’ FESTIVAL 2007 • MAY 23 – 27 www.artswithoutborders.ca MUSGRAVE AGENCIES is proud to support Lloydminster Realtors’ Arts Without Borders Festival Join us for the Buffalo Twins Mural Mosaic Unveiling on May 26 at 12:30 pm outside at entrance to Vic Juba Community Theatre (north door) SCHEDULE OF FESTIVAL EVENTS Page May 23 (Wednesday) Lloydminster Reads - Featuring The Garneau Block written by Todd Babiak 6 Writers Room 7 Juried Fine Art & Fine Crafts Show 18 Best of Alberta Film 20 May 24 (Thursday) Writers Room 7 ArtWalk 8 Arts Unleashed Visual Arts Demonstrations 12 Visual Arts Workshops 12 Taste of Lloydminster Food Fair & Outdoor Stage 12 Juried Art Prize Presentations 13 Quick Draw 13 Silent Auction 13 Juried Fine Art & Fine Crafts Show 18 Best of Alberta Film 20 May 25 (Friday) It’s Your Turn 7 Writers Room 7 ArtWalk 8 Art Appraisal 14 Public Forum with the Nominees - Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Arts Awards 2007 15 Rock Cabaret - Featuring Stripped Down Radio and Freddie & the Axemen 16 Juried Fine Art & Fine Crafts Show 18 Best of Alberta Film 20 May 26 (Saturday) Writers’ Guild of Alberta with Kelly Clemmer 7 Public Reading by Marty Chan of his Children’s Books 7 Writers Room 7 ArtWalk 8 Juried Fine Art & Fine Crafts Show 18 Best of Alberta Film 20 Arts Volunteer Award 22 Arts Bursary 22 Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Arts Awards 2007 22 May 27 (Sunday) Marty Chan Playwriting Workshop 7 Writers Room 7 Juried Fine Art & Fine Crafts Show 18 3 MESSAGES Arts Without Borders Festival Society was deeply honoured when our bid to host the 2007 Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Arts Awards Gala was accepted by the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Arts Awards Foundation. -

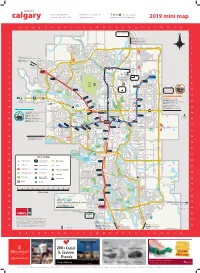

2019 Mini Map

phone: 403-263-8510 [email protected] /tourismcalgary toll free: 1-800-661-1678 visitcalgary.com #capturecalgary | #askmeyyc 2019 mini map A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z ? 1 58 10 1 Airdrie 13 km / 8 miles SY MON Drumheller 117 km / 73 miles S VA L Red Deer 128 km / 80 miles 2 L 2 E Y Edmonton 278 km / 173 miles 144 AV NW R S D H A N G W A 3 N #201 W #201 E STONEY TR NE 3 A P P K I E T E R R C N E W S O R 4 T 4 N T O FO Cochrane 17 km / 10 miles ER W E to Yamnuska Wolfdog Sanctuary 31 km / 19 miles EST D 13 NO 5 S 5 Banff (alternate route) E COUNTRY HILLS BV NE C 117 km / 73 miles R TR E E K 6 36 ST NE 6 43 ARLOW 96 B Spring Hill RV Park AV NE 300 NW 300 300 27 km / 17 miles COUNTRY HILLS BV 300 AIRPORT TRAIL (96 AV NE) TUNNEL 7 Tuscany BEDDINGT 62 7 W 44 ST NE N R ON ? 300 W T TR N I NOSE HILL DR P P R 300 80 AV NE Saddletowne T A 8 8 N YYC CALGARY Y A E Crowfoot 14 ST NW 300 G N TR NW INTERNATIONAL A O H T R Martindale S S AIRPORT 60 T CRO S SARCEE NOSE I 9 WCHILD T 9 300 Deerfoot E HILL City M 64 AV NE TR NW McKnight/ PARK 64 AV NE Westwinds t 66 r o JOHN LA 10 rp Dalhousie 10 BO i W R A I o V t BOWNESS URIE BV 300 ER E 29 14 1 PARK McKNIGHT BV 0 2 11 Calaway Park # 50 McKNIGHT BV 11 6 km / 4 miles 33 40 Hangar Flight 300 Museum 36 ST NE Brentwood Chestermere 8 km / 5 miles Calgary West Canada’s CF 34 Whitehorn Calaway RV Park Campground Market N Sports O DEERFOO Strathmore 38 km / 24 miles 12 & Campground Mall 12 Hall of Fame 19 University S 72 32 AV NE Dinosaur Prov. -

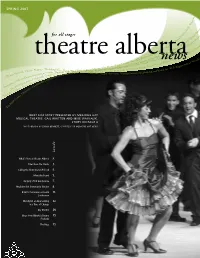

SPRING 2007 Y a L

s r e SPRING 2007 y a l P s k r o w r e t a W 0 7 s 9 r 1 e ( y y la t P ie e for all stages oc tr y S ea et a h ci m T o ts ra ill S c D re je k dm at ro oc in he P stl W T re e rs et at l W ye pp he oo ety Pla Pu T h ci e P. ta Sc So gu . er e rts Ro e W lb dl g A he atr A id in s T he ety M form Art ry T oci n Per ine yste a S ave ills of F o M ram dh o H lty ertig rs D oo Tw Facu d V newslaye W tre ry an P l Thea alga he Gr aviar hoo outh y of Cn - at t ty C er Sc ouse Y iverJsuitnctio a Socie agn Tree H r t Ts hUenatre t Dram . P. W spero Workshop W f Hintonheatrfe FCinaleg Aar d Distric Art W eatre Pro est Theat st T h7e5a t rTeo Rwens toaura nFta cTulty o Beaumont an Visual rk Th o Theatre)l S t a g r e T W h e a tr r a em a i t yic o Af rCtsa l gAalrbyerta Lyric Theatre rming and etwo ent (Studi Schoo m ayn dU Dnivers Walterdale Theatre Associates Victoria School of Perfo re N partm posite Ahceadtree heat a De Com eb obfe rT T ram ville ld Went ta D egre Gui rtm ber l V yers epa Al hoo Pla D of Sc tre dge ity igh hea bri ers H n T th iv ills isio Le n H V of U wo ry y T lga sit Ca er S.