Expanding Medi-Cal Profiles of Potential New Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Newsletter October 2000

October 2000 Monthly Newsletter From the Commodore Board of Directors Commodore Rob Wilson Im. Past Commodore Voldi Maki As I told you in a previous Telltale, dock, moving an existing dock to Vice Commodore Phil Spletter we are taking advantage of the low this location, or moving a small Secretary Gail Bernstein lake level to prepare for some pos- dock if we reduce the length of one Treasurer Becky Heston sible harbor modifications. Using or more of our existing docks. the recently completed topographic Race Commander Bob Harden Project 3 - Widen the north Buildings & Grounds Michael Stan survey, Ray Schull and Tom Groll have prepared some prelimi- ramp. This proposal is to ex- Fleet Commander Doug Laws cavate the area to allow us to Sail Training Brigitte Rochard nary plans for three possible modifications to the harbor. double the width of the current ramp. This would allow for AYC Staff Project 1 - Excavate the area multiple boats to launch/ General Manager Nancy Boulmay under the regular location of Docks retrieve and greatly reduce the Office Manager Cynthia Eck 2 - 6. This project would allow the congestion and waiting required at Caretakers Tom Cunningham docks to remain in their regular lo- the ramp. This work will also re- Vic Farrow cation until the lake level reaches duce the silt buildup on the ramp 655’. Currently docks 4, 5, and 6 by properly sloping back the have been relocated to the point ground from the new ramp edge. Austin Yacht Club approximately 21% of the time We also propose to repair the ero- 5906 Beacon Drive since 1980. -

NATURAL GAS MARKET UPDATE August 30, 2019 8/23/2019 2,857

NATURAL GAS MARKET UPDATE NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER HURRICANE DORIAN FORECAST CONE: August 30, 2019 Snyder Brothers Inc., Gas Marketing 1 Glade Park East, P.O. Box 1022 Kittanning, PA 16201 Ph: 724-548-8101 Fax 724-545-8243 www.snyderbrothersinc.com NYMEX HENRY HUB SETTLEMENT PRICES: 8/30/19 Settle Season Year Oct19 2.285 Nov19-Mar20 2.485 Cal 20 2.401 Nov19 2.324 Apr20-Oct20 2.314 Cal 21 2.454 Dec19 2.485 Nov20-Mar21 2.586 Cal 22 2.496 WORKING NATURAL GAS IN STORAGE, LOWER 48 STATES: Jan20 2.588 Apr21-Oct21 2.350 Cal 23 2.577 As of Week Ending: 8/23/2019 Build/ (Draw) Feb20 2.556 Nov21-Mar22 2.633 Cal 24 2.648 Current Storage 2,857 Bcf +60 Bcf Surplus/ (Deficit) Mar20 2.473 Apr22-Oct22 2.388 Cal 25 2.745 Last Year Storage 2,494 Bcf 363 Bcf Apr20 2.277 Nov22-Mar23 2.676 Cal 26 2.852 5-Year Average 2,957 Bcf (100) Bcf May20 2.261 Apr23-Oct23 2.477 Cal 27 2.961 ICE Traded Markets: ICE Settle: Jun20 2.297 Nov23-Mar24 2.777 Cal 28 3.070 Weekly Storage Inventory Number (09/05/2019) +80 Bcf End of Injection Season Storage (11/14/2019) 3,747 Bcf DOMINION-SOUTH FIXED-PRICE MARKETS (NYMEX/HENRY+ ICE DOM-SOUTH BASIS: Oct-19 1.5325 Oct-19 1.5325 Market Commentary : The natural gas market seems to be sitting on Nov-19 1.7765 Nov19-Mar20 2.1142 firmer ground at the moment, after what has been a fairly interesting trading week. -

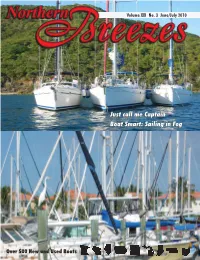

Sailing in Fog Just Call Me Captain Boat Smart

Volume XXI No. 3 June/July 2010 Just call me Captain Boat Smart: Sailing in Fog Over 500 New and Used Boats on North Sails quality, durability Call for 2010 Dockage & performance! MARINA & SHIP’S STORE Downtown Bayfield Seasonal & Guest Dockage, Nautical Gifts, Clothing, Boating Supplies, Parts & Service 715-779-5661 It’s easy to measure your own boatt and SAVE on the world’s best cruising and racing sails. Log on to Free tape northsailsdirect.net measure or call 888-424-7328. with every apostleislandsmarina.net order! 2 Visit Northern Breezes Online @ www.sailingbreezes.com - June/July 2010 New New VELOCITEK On site INSTRUMENTS Sail repair IN STOCK AT Quick, quality DISCOUNT service PRICES Do it Seven Seas is now part of Shorewood Marina • Same location on Lake Minnetonka Lake Minnetonka’s • Same great service, rigging, hardware, cordage, paint Premier Sailboat Marina • Inside boat hoist up to 27 feet—working on boats all winter • New products—Blue Storm inflatable & Stohlquist PFD’s, Limited Slips Rob Line high-tech rope Summer Hours Still Available! Mon-Fri Open Late 8-5 Mondays Sat 9-3 Closed Sundays Till 7pm 600 West Lake St., Excelsior, MN 55331 952-474-0600 Just ½ mile north of Hwy 7 on Co. Rd. 19 [email protected] 952-470-0099 www.shorewoodyachtclub.com S A I L I N G S C H O O L Safe, fun, learning Learn to sail on Three Metro Lakes; Also Leech Lake, MN; Pewaukee Lake, WI; School of Lake Superior, Apostle Islands, Bayfield, WI; Lake Michigan; Caribbean Islands the Year On-the-water courses weekends, week days, evenings -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Scoring Summary (Final) 2016 Cal Football Hawai'i Vs California (Aug 27, 2016 at Sydney, Australia)

Scoring Summary (Final) 2016 Cal Football Hawai'i vs California (Aug 27, 2016 at Sydney, Australia) Hawai'i (0-1) vs. California (1-0) Date: Aug 27, 2016 • Site: Sydney, Australia • Stadium: ANZ Stadium Attendance: 61247 Score by Quarters 1 2 3 4 Total Hawai'i 14 0 10 7 31 California 17 17 7 10 51 Qtr Time Scoring Play V-H 1st 13:56 CAL - Muhammad, Khalfani 34 yd run (Anderson, Matt kick), 6-48 1:04 0 - 7 07:39 UH - KEMP, Marcus 39 yd pass from WOOLSEY, Ikaika (SANCHEZ, R. kick), 8-83 3:19 7 - 7 05:13 CAL - Hansen, Chad 17 yd pass from Webb, Davis (Anderson, Matt kick), 10-61 2:22 7 - 14 03:50 UH - SAINT JUSTE, D. 53 yd run (SANCHEZ, R. kick), 3-64 1:17 14 - 14 01:36 CAL - Anderson, Matt 29 yd field goal, 5-41 2:05 14 - 17 2nd 04:00 CAL - Anderson, Matt 22 yd field goal, 18-87 7:21 14 - 20 03:43 CAL - Hansen, Chad 34 yd pass from Webb, Davis (Anderson, Matt kick), 1-34 0:08 14 - 27 00:07 CAL - Webb, Davis 4 yd run (Anderson, Matt kick), 8-85 1:35 14 - 34 3rd 11:50 UH - SANCHEZ, R. 42 yd field goal, 8-59 3:05 17 - 34 08:18 CAL - Stovall, Melquise 14 yd pass from Webb, Davis (Anderson, Matt kick), 9-73 3:27 17 - 41 02:04 UH - LAKALAKA, S. 4 yd run (SANCHEZ, R. kick), 15-84 6:11 24 - 41 4th 10:08 CAL - Anderson, Matt 25 yd field goal, 9-32 2:12 24 - 44 07:01 CAL - Veasy, Jordan 33 yd pass from Webb, Davis (Anderson, Matt kick), 5-70 1:13 24 - 51 03:40 UH - HARRIS, Paul 15 yd run (SANCHEZ, R. -

2009 Year Book

2009 YEAR BOOK www.massbaysailing.org $5.00 HILL & LOWDEN, INC. YACHT SALES & BROKERAGE J boat dealer for Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire Hill & Lowden, Inc. offers the full range of new J Boat performance sailing yachts. We also have numerous pre-owned brokerage listings, including quality cruising sailboats, racing sailboats, and a variety of powerboats ranging from runabouts to luxury cabin cruisers. Whether you are a sailor or power boater, we will help you find the boat of your dreams and/or expedite the sale of your current vessel. We look forward to working with you. HILL & LOWDEN, INC. IS CONTINUOUSLY SEEKING PRE-OWNED YACHT LISTINGS. GIVE US A CALL SO WE CAN DISCUSS THE SALE OF YOUR BOAT www.Hilllowden.com 6 Cliff Street, Marblehead, MA 01945 Phone: 781-631-3313 Fax: 781-631-3533 Table of Contents ______________________________________________________________________ INFORMATION Letter to Skippers ……………………………………………………. 1 2009 Offshore Racing Schedule ……………………………………………………. 2 2009 Officers and Executive Committee ……………………………............... 3 2009 Mass Bay Sailing Delegates …………………………………………………. 4 Event Sponsoring Organizations ………………………………………................... 5 2009 Season Championship ………………………………………………………. 6 2009 Pursuit race Championship ……………………………………………………. 7 Salem Bay PHRF Grand Slam Series …………………………………………….. 8 PHRF Marblehead Qualifiers ……………………………………………………….. 9 2009 J105 Mass Bay Championship Series ………………………………………… 10 PHRF EVENTS Constitution YC Volvo Ocean Race Challenge ……………………………………… 11 Constitution YC Wednesday -

JUNE 1981 AUSTIN YACHT CLUB 5906 Beacon Drive Austin, Texas 78734

JUNE 1981 AUSTIN YACHT CLUB 5906 Beacon Drive Austin, Texas 78734 Business Office 266-1336 Clubhouse 266-1897 Cor;imodore-----------------------------------------------Russell Pa inton Immediate Past Corrmodore---------------------Frank Arakel (Jl.rak) Bozyan Vice Coumodore-------------------------------------- -Raymond (Ray) Lott Secretary-----------------------------------------Homer S. (Hap) Arnold Treasurer-------------------------------------------Trenton \:. \1ann Jr. Race Commander------------------------------------ ·James W. (Jir,1 ) 3aker Uu ildings and Grounds Conmander------------------------- Carl B. Morris Fleet Conmander------------------------------------M. J. (Hap ) McCollum Tell Tale Editor--•••••-------------------------------------------Pat Halter Assistant Ed itor-------------------------------------------Carol Shough Fleet Reporters: Coronado 15---------------------------------------------Dan O' Donnell Ensign-------------------------------------------------Eugene English Fireball ·--------------------------------------------------Teri Nelms J-24-------------------------------------------------------Jane Ashby Keel Handicap--------------------------------------------Bill Records Laser----------------------------------------------------Robert Young i'l-20 ------------------------------------------------Francis Mcintyre Southcoast 21 ------------------------------------~--------Greta Rymal Thistle ----------------------------------------------Merrill Goodwyn \ ~ t;,;,,,JJ/,,,,1 FROM THE COMMODORE In keepiny with riy -

03FB Guide P151-179

INTERCOLLEGIATE RESULTS AIR FORCE CARLISLE vs. CALIFORNIA vs. CALIFORNIA Cal leads series, 4-2 Carlisle leads series, 1-0 1961-Air Force, 15-14 (B) 1899-Carlisle, 2-0 (SF) 1965-Cal, 24-7 (USAF) 1967-Cal, 14-12 (B) CLEMSON 1975-Cal, 31-14 (USAF) vs. CALIFORNIA 1977-Cal, 24-14 (B) Cal leads series, 1-0 2002-Air Force, 23-21 (B) 1991-*Cal, 37-13 (Orlando) (Points-Cal 128, Falcons 85) (Points-Cal 37, Clemson 13) *1992 Florida Citrus Bowl ALABAMA vs. CALIFORNIA COLORADO Series tied, 1-1 vs. CALIFORNIA 1937-*Cal, 13-0 (Pasadena) Series tied, 2-2 1973-Alabama, 66-0 (Birmingham) 1968-Cal, 10-0 (B) (Points-Alabama 66, Cal 13) 1972-Colorado, 20-10 (Boulder) *1938 Rose Bowl 1975-Colorado, 34-27 (Boulder) 1982-Cal, 31-17 (Boulder) ARIZONA (Points-Cal 78, Colorado 71) vs. CALIFORNIA Arizona leads series, 11-9-2 DUKE 1978-Cal, 33-20 (Tucson) vs. CALIFORNIA 1979-Cal, 10-7 (Tucson) Duke leads series, 1-0-1 1980-Arizona, 31-24 (B) 1962-Duke, 21-7 (Durham) 1981-Cal, 14-13 (Tucson) 1963-Tie, 22-22 (B) 1983-Tie, 33-33 (B) (Points-Duke 43, Cal 29) 1984-Arizona, 23-13 (Tucson) FLORIDA 1985-Arizona, 23-17 (B) Cal’s Jim Turner (#79) runs down Navy ball carrier William Earl during a 1986-Arizona, 33-16 (Tucson) 1947 showdown at Berkeley before an overflow crowd of 83,000, the vs. CALIFORNIA 1987-Tie, 23-23 (B) largest ever to see a game at Cal. Florida leads series, 2-0 1988-Cal, 10-7 (Tucson) 1974-Florida, 21-17 (Gainesville) 1989-Cal, 29-28 (B) 1980-Florida, 41-13 (Tampa) 1990-Cal, 30-25 (Tucson) 1994-Cal, 25-21 (B) 1956-Baylor, 7-6 (B) (Points-Florida 62, Cal 30) 1991-Cal, 23-21 (Tucson) 1995-ASU, 38-29 (B) 2002-Cal, 70-22 (B) 1992-Arizona, 24-17 (B) FRESNO STATE 1996-ASU, 35-7 (Tempe) (Points-Cal 76, Baylor 54) 1993-Cal, 24-20 (B) 1997-ASU, 28-21 (B) vs. -

High-Low-Mean PHRF Handicaps

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages list low, high and average performance handicaps reported by USPHRF Fleets for over 4100 boat classes/types. Using Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, information can be displayed for each boat class upon request. Class names conform to USPHRF designations. The source information for this listing also provides data for the annual PHRF HANDICAP listings (The Red, White, & Blue Book) published by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION. This publication also lists handicaps by Class/Type, Fleet, Confidence Codes, and other useful information. Precautions: Handicap data represents base handicaps. Some reported handicaps represent determinations based upon statute rather than nautical miles. Some of the reported handicaps are based upon only one handicapped boat. The listing covers reports from affiliated fleets to USPHRF for the period March 1995 to June 2008. This listing is updated several times each year. HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS ORGANIZED BY CLASS/TYPE Lowest Highest Average Class\Type Handicap Handicap Handicap 10 METER 60 60 60 11 METER 69 108 87 11 METER ODR 72 78 72 1D 35 27 45 33 1D48 -42 -24 -30 22 SQ METER 141 141 141 30 SQ METER 135 147 138 5.5 METER 156 180 165 6 METER 120 158 144 6 METER MODERN 108 108 108 6.5 M SERIES 108 108 108 6.5M 76 81 78 75 METER 39 39 39 8 METER 114 114 114 8 METER (PRE WW2) 111 111 111 8 METER MODERN 72 72 72 ABBOTT 22 228 252 231 ABBOTT 22 IB 234 252 -

11 Meter Od Odr *(U)* 75 1D 35 36 1D 48

11 METER OD ODR *(U)* 75 1D 35 36 1D 48 -42 30 SQUARE METER *(U)* 138 5.5 METER ODR *(U)* 156 6 METER ODR *(U)* Modern 108 6 METER ODR *(U)* Pre WW2 150 8 METER Modern 72 8 METER Pre WW2 111 ABBOTT 33 126 ABBOTT 36 102 ABLE 20 288 ABLE 42 141 ADHARA 30 90 AERODYNE 38 42 AERODYNE 38 CARBON 39 AERODYNE 43 12 AKILARIA class 40 RC1 -6/3 AKILARIA Class 40 RC2 -9/0 AKILARIA Class 40 RC3 -12/-3 ALAJUELA 33 198 ALAJUELA 38 216 ALBERG 29 225 ALBERG 30 228 ALBERG 35 201 ALBERG 37 YAWL 162 ALBIN 7.9 234 ALBIN BALLAD 30 186 ALBIN CUMULUS 189 ALBIN NIMBUS 42 99 ALBIN NOVA 33 159 ALBIN STRATUS 150 ALBIN VEGA 27 246 Alden 42 CARAVELLE 159 ALDEN 43 SD SM 120 ALDEN 44 111 ALDEN 44-2 105 ALDEN 45 87 ALDEN 46 84 ALDEN 54 57 ALDEN CHALLENGER 156 ALDEN DOLPHIN 126 ALDEN MALABAR JR 264 ALDEN PRISCILLA 228 ALDEN SEAGOER 141 ALDEN TRIANGLE 228 ALERION XPRS 20 *(U)* 249 ALERION XPRS 28 168 ALERION XPRS 28 WJ 180 ALERION XPRS 28-2 (150+) 165 ALERION XPRS 28-2 SD 171 ALERION XPRS 28-2 WJ 174 ALERION XPRS 33 120 ALERION XPRS 33 SD 132 ALERION XPRS 33 Sport 108 ALERION XPRS 38Y ODR 129 ALERION XPRS 38-2 111 ALERION XPRS 38-2 SD 117 ALERION 21 231 ALERION 41 99/111 ALLIED MISTRESS 39 186 ALLIED PRINCESS 36 210 ALLIED SEABREEZE 35 189 ALLIED SEAWIND 30 246 ALLIED SEAWIND 32 240 ALLIED XL2 42 138 ALLMAND 31 189 ALLMAND 35 156 ALOHA 10.4 162 ALOHA 30 144 ALOHA 32 171 ALOHA 34 162 ALOHA 8.5 198 AMEL SUPER MARAMU 120 AMEL SUPER MARAMU 2000 138 AMERICAN 17 *(U)* 216 AMERICAN 21 306 AMERICAN 26 288 AMF 2100 231 ANDREWS 26 144 ANDREWS 36 87 ANTRIM 27 87 APHRODITE 101 135 APHRODITE -

North American Portsmouth Yardstick Table of Pre-Calculated Classes

North American Portsmouth Yardstick Table of Pre-Calculated Classes A service to sailors from PRECALCULATED D-PN HANDICAPS CENTERBOARD CLASSES Boat Class Code DPN DPN1 DPN2 DPN3 DPN4 4.45 Centerboard 4.45 (97.20) (97.30) 360 Centerboard 360 (102.00) 14 (Int.) Centerboard 14 85.30 86.90 85.40 84.20 84.10 29er Centerboard 29 84.50 (85.80) 84.70 83.90 (78.90) 405 (Int.) Centerboard 405 89.90 (89.20) 420 (Int. or Club) Centerboard 420 97.60 103.40 100.00 95.00 90.80 470 (Int.) Centerboard 470 86.30 91.40 88.40 85.00 82.10 49er (Int.) Centerboard 49 68.20 69.60 505 (Int.) Centerboard 505 79.80 82.10 80.90 79.60 78.00 747 Cat Rig (SA=75) Centerboard 747 (97.60) (102.50) (98.50) 747 Sloop (SA=116) Centerboard 747SL 96.90 (97.70) 97.10 A Scow Centerboard A-SC 61.30 [63.2] 62.00 [56.0] Akroyd Centerboard AKR 99.30 (97.70) 99.40 [102.8] Albacore (15') Centerboard ALBA 90.30 94.50 92.50 88.70 85.80 Alpha Centerboard ALPH 110.40 (105.50) 110.30 110.30 Alpha One Centerboard ALPHO 89.50 90.30 90.00 [90.5] Alpha Pro Centerboard ALPRO (97.30) (98.30) American 14.6 Centerboard AM-146 96.10 96.50 American 16 Centerboard AM-16 103.60 (110.20) 105.00 American 17 Centerboard AM-17 [105.5] American 18 Centerboard AM-18 [102.0] Apache Centerboard APC (113.80) (116.10) Apollo C/B (15'9") Centerboard APOL 92.40 96.60 94.40 (90.00) (89.10) Aqua Finn Centerboard AQFN 106.30 106.40 Arrow 15 Centerboard ARO15 (96.70) (96.40) B14 Centerboard B14 (81.00) (83.90) Balboa 13 Centerboard BLB13 [91.4] Bandit (Canadian) Centerboard BNDT 98.20 (100.20) Bandit 15 Centerboard -

Valid List, Design &

Date: 09/20/2007 2007 Valid List by Design, Adjustments Page 1 of 29 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's rating, and valid date, and should not be used to establish ratings for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustment, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicapt Design Last Name Yacht Name Record Date Base LP Spn Rig Prop Rec Misc Race Cruise 12 METER GREGORY VALIANT R020107 3 3 9 12 METER HANOVER COLUMBIA R052407 15 15 21 12 Meter Hill Weatherly R052407 15 15 21 12 METER MC MILLEN III ONAWA R012707 33 -6 27 33 ?? Mc Neill ?? R061907 108 +6 114 123 Able Marine Urban Chikadee 111 N032307 102 +9 +6 +6 123 135 Advance 245 Meincke Kestrel N052407 201 -3 198 204 AERODYNE 38 DALESSANDROALEXIS R041607 39 39 48 Aerodyne 38 Manchester Wazimd R070207 39 39 48 Aerodyne 43 Millet TANGO R033107 12 12 21 ALBERG 35 PREFONTAINE HELIOS R050207 201 -3 198 210 Alberg 37 Mintz L' Amarre R052607 162 +6 3 +6 177 192 ALBIN CUMULUS DROSTE CUMULUS 3 R050707 189 189 204 Alden Smith Muskrat N071907 156 +3 +6 165 180 Alden 44 Weisman Nostos N020307 111 +9 +6 126 129 ALDEN 54 TM ANDERSON ANGEL R021207 57 -15 42 54 Alerion 28 Michele Gambit N072607 177 U177 U186 Alerion 28-2 Johnston Summer Salt N072707 174 U174 U183 Alerion 28-2 Swett Winderlust R041607 174 174 186 Alerion 33 Cressy, Bryant Alerion 33 N050207 120 120 129 Alerion 38-2 Cressy,