Ana Menéndez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time Songs (PDF)

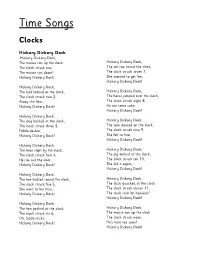

Time Songs Clocks Hickory Dickory Dock Hickory Dickory Dock, The mouse ran up the clock. Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck one, The cat ran round the clock, The mouse ran down! The clock struck seven 7, Hickory Dickory Dock. She wanted to get 'em, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bird looked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck two 2, The horse jumped over the clock, Away she flew, The clock struck eight 8, Hickory Dickory Dock! He ate some cake, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The dog barked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck three 3, The cow danced on the clock, Fiddle-de-dee, The clock struck nine 9, Hickory Dickory Dock! She felt so fine, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bear slept by the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck four 4, The pig oinked at the clock, He ran out the door, The clock struck ten 10, Hickory Dickory Dock! She did it again, Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The bee buzzed round the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck five 5, The duck quacked at the clock She went to her hive, The clock struck eleven 11, Hickory Dickory Dock! The duck said 'oh heavens!' Hickory Dickory Dock! Hickory Dickory Dock, The hen pecked at the clock, Hickory Dickory Dock, The clock struck six 6, The mouse ran up the clock Oh, fiddle-sticks, The clock struck noon Hickory Dickory Dock! He's here too soon! Hickory Dickory Dock! We're Gonna Rock Around the Clock What time is it, Mr Wolf? Bill Haley & His Comets by Richard Graham One, -

How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates Gary M. Bogers University of Central Florida Part of the Music Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bogers, Gary M., "Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 511. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/511 MUSIC AND THE PRESIDENCY: HOW CAMPAIGN SONGS SOLD THE IMAGE OF PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES by GARY MICHAEL BOGERS JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Music Performance in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Dr. Scott Warfield Co-chairs: Dr. Alexander Burtzos & Dr. Joe Gennaro ©2019 Gary Michael Bogers Jr. ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I will discuss the importance of campaign songs and how they were used throughout three distinctly different U.S. presidential elections: the 1960 campaign of Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy against Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon, the 1984 reelection campaign of President Ronald Wilson Reagan against Vice President Walter Frederick Mondale, and the 2008 campaign of Senator Barack Hussein Obama against Senator John Sidney McCain. -

“Oh, Happy Days”: Milwaukee & the Wisconsin Dells

Moderate May 31 to June 6, 2021 11 6 Pace “Oh, Happy Days”: Milwaukee & The Wisconsin Dells Milwaukee lies along the shores of Lake Michigan at the union of three rivers – the Menomonee, the Kinnickinnic and the Milwaukee. Known for its breweries, the MLB Brewers, and a “big city of little neighborhoods”, Milwaukee’s unique neighborhoods create a one of a kind culture, where you’ll see architecture designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The city was also made famous by the TV series “Happy Days” and “Laverne & Shirley”. Delight in a selfie with a bronze statue of the “Fonz”! Experience the natural beauty, wonder and mystery of the Wisconsin Dells during a leisurely boat cruise. Ride in a quaint horse-drawn carriage through a mile of cliff walled gorges. Visit the International Crane Foundation, a nonprofit conservation organization protecting cranes and conserving ecosystems, watersheds and flyways on which the cranes depend. Tour Highlights & Inclusions • Deluxe coach transportation with wifi, air-conditioned, washroom equipped • Two-nights’ accommodation at the Hampton Inn of Holland, MI • Two-nights’ accommodation at the Drury Plaza Hotel Milwaukee Downtown • Two-nights’ accommodation at the Hampton Inn & Suites Wisconsin Dells • Breakfast daily, one box lunch and four dinners • Guided tour of Milwaukee, and the International Crane Foundation • Lost Canyon Tour on horse drawn carriage • Tour two of Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs – SC Johnson Headquarters, and Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church • Guided tour of the Harley-Davidson Museum, Pabst -

Happy Days Are Here Again 4/4 1...2...1234

HAPPY DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN 4/4 1...2...1234 So long, sad times, go 'long, bad times, we are rid of you at last Howdy, gay times, cloudy gray times, you are now a thing of the past Happy days are here again, the skies above are clear a-gain So let's sing a song of cheer a-gain, happy days are here a-gain Altoge-ther, shout it now, there's no one who can doubt it now So let's tell the world a-bout it now, happy days are here a-gain Your cares and troubles are gone, there'll be no more from now on, from now on Happy days are here a-gain, the skies above are clear again So let's sing a song of cheer a-gain, happy days are here a-gain So let's sing a song of cheer a-gain, happy days..... are..... here..... a-gain HAPPY DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN 4/4 1...2...1234 Am G F E7 Am E7 E7+ Am So long sad times, go long bad times, we are rid of you at last Am G B7 E7 C#m7 F#7 B7 E7 Howdy, gay times, cloudy gray times, you are now a thing of the past A E7+ A E7+ A E7+ A Happy days are here again, the skies above are clear a-gain Bbdim Bm7 E7 Bm7 E7 A D A E7 So let's sing a song of cheer a-gain, happy days are here a-gain A E7+ A E7+ A E7+ A Altoge-ther, shout it now, there's no one who can doubt it now Bbdim Bm7 E7 Bm7 E7 A D A So let's tell the world a-bout it now, happy days are here a-gain C# G#7 C# B7 E B7 E7 F7 Your cares and troubles are gone, there'll be no more from now on, from now on Bb F#+ Bb F#+ Bb F#+ Bb Happy days are here a-gain, the skies above are clear again Bdim Cm7 F7 Cm7 F7 Bb Eb Bb So let's sing a song of cheer a-gain, happy days are here a-gain Bdim Cm7 F7 Cm7 F7 Bb Eb Bb F#+ Bb So let's sing a song of cheer a-gain, happy days... -

Happy Days a New Musical Book by Music & Lyrics Garry Marshall by Paul Williams

Please Enjoy the Following Sample • This sample is an excerpt from a Samuel French title. • This sample is for perusal only and may not be used for performance purposes. • You may not download, print, or distribute this excerpt. • We highly recommend purchasing a copy of the title before considering for performance. For more information about licensing or purchasing a play or musical, please visit our websites www.samuelfrench.com www.samuelfrench-london.co.uk Happy Days A New Musical Book by Music & Lyrics Garry Marshall by Paul Williams Based on the Paramount Pictures Television Series “Happy Days” created by Garry Marshall Arrangements and Orchestrations by John McDaniel A Samuel French Acting Edition samuelfrench.com Copyright © 2010 by CBS Studios, Inc. Happy Days Artwork Copyright © 2010 Henderson Production Co., Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that HAPPY DAYS - A NEW MUSICAL is subject to a Licensing Fee. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, the British Commonwealth, including Canada, and all other countries of the Copy- right Union. All rights, including professional, amateur, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. In its present form the play is dedicated to the reading public only. The amateur live stage performance rights to HAPPY DAYS, A NEW MUSICAL are controlled exclusively by Samuel French, Inc., and licens- ing arrangements and performance licenses must be secured well in advance of presentation. PLEASE NOTE that amateur Licensing Fees are set upon application in accordance with your producing circum- stances. -

“Happy Days Are Here Again”: the Song That Launched FDR's

“Happy Days Are Here Again”: The Song That Launched FDR’s Presidency In 1929, just prior to the Great Crash of the New York Stock Market, Milton Ager and Jack Yellen recorded, “Happy Days Are Here Again.” The song was an instant hit and would remain a popular refrain throughout the 1930s, as the theme of radio shows sponsored by Lucky Strike cigarettes. In 1932, the song became closely associated to the presidential campaign of New York Democratic Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his effort to unseat incumbent President Herbert Hoover. When Roosevelt arrived in Chicago to accept his party’s nomination for president, he entered the room to the sound of “Happy Days Are Hear Again.” The song and its cheerful lyrics matched Roosevelt’s upbeat tempo and stood in stark contrast to Hoover’s demeanor. In addition, the song resonated throughout the nation as most Americans were looking to Roosevelt in hopes that his pledge of “a new deal for the American people” would usher them safely through the Great Depression into a new era of economic prosperity. “Happy Days Are Here Again” has long been associated with the Democratic party, and remains a sentimental favorite for its political leaders and supporters such as singer and actress Barbara Streisand, who has recorded her own version of the song. “Happy Days Are Here Again” is listed as #47 on the Recording Industry Association of America's list of "Songs of the Century". ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- “Happy Days Are Here Again” by Jack Yellen & Milton Alger As recorded by Leo Reisman and His Orchestra, with Lou Levin, vocal (November 1929) for the 1930 MGM movie Chasing Rainbows . -

FWWH Revised Songbook ―This Camp Was Built to Music Therefore Built Forever

FWWH Revised Songbook Revised Summer 2011 ―This camp was built to music therefore built forever‖ These are the songs sung by Four Winds and Westward Ho campers – songs that have expressed their interests and ideals through the years. As you sing the songs again, may they recall memories of sunny days, and some misty and rainy ones too, of sailing on sparkling blue water, of cantering along leafy trails, of exploring the beach when the tide is out. May these songs remind you of unexpected adventure, and of friendships formed through the sharing of Summer days, working and playing together. 1 Index of songs A Gypsy‘s Life…………………………………………………….7 A Junior Song……………………………………………………..7 A Walking Song………………………………….…….………….8 Across A Thousand Miles of Sea…………..………..…………….8 Ah, Lovely Meadows…………………………..……..…………...9 All Hands On Deck……………………………………..……..…10 Another Fall…………………………………...…………………10 The Banks of the Sacramento…………………………………….…….12 Big Foot………………………………………..……….………………13 Bike Song……………………………………………………….…..…..14 Blow the Man Down…………………………………………….……...14 Blowin‘ In the Wind…………………………………………………....15 Boy‘s Grace…………………………………………………………….16 Boxcar……………………………………………………….…..……..16 Canoe Round…………………………………………………...………17 Calling Out To You…………………………………………………….17 Canoe Song……………………………………………………………..18 Canoeing Song………………………………………………………….18 Cape Anne………………………………………………...……………19 Carlyn…………………………………………………………….…….20 Changes………………………………………………………………...20 Christmas Night………………………………………………………...21 Christmas Song…………………………………………………………21 The Circle Game……………………………………………………..…22 -

Hollywood Auction 74

Hollywood Auction 74 372 1-310-859-7701 “The Fonz” Triumph Trophy TR5 1065. HENRY WINKLER “ A RT H UR ‘ T H E F ONZ ’ F ONZARELLI ” SIGNATURE T RIUMP H T ROP H Y TR 5 MOTOR C Y C LE FROM H APPY D AYS . (Paramount TV 1974-84) This is the motor- cycle that helped make Arthur Fonzarelli, “The Fonz,” The icon of cool – the 1949 Triumph Trophy 500 Custom (frame number TC11198T). Originally a bit player, Fonzie/Winkler, became the breakout star of Happy Days — the long running ABC sitcom watched by some 40 million Americans at its ratings peak. The bike was originally owned by Hollywood stuntman, racer and provider of bikes to the studios Bud Ekins (it was Ekins who actually jumped the barbed-wire fence in The Great Escape, doubling for his friend Steve McQueen). This ‘49 Triumph is one of three Triumph motorcycles “The Fonz” used during the show’s 10-year run on ABC. According to Bud Ekins, all three Triumphs used on the show were 500cc Trophy models of various years – two of which went missing/stolen, or raced to the ground and sold for parts. Eventually, when the show ended, Ekins sold the third and only remaining “Fonzie” Triumph to friend and motorcycle collector Mean Marshall Ehlers where it resided since 1990. Designed to accommodate Henry Winkler’s inability to ride larger bikes, Ekins had supplied Paramount’s show producers with the beat-up Scrambler, yanking off the front fender, bolted on a set of buckhorn handle bars and spray painted the fuel tank silver. -

Working in Partnership with Other Setting Policy

Working in Partnership with Other Setting Policy I am committed to developing strong relationships with other professionals and agencies involved in children’s lives, to support their learning and development and to promote safeguarding and child protection. Working with others - EYFS requirement 3.67 – Providers must enable a regular two-way flow of information between providers, if a child is attending more than one setting. I inform parents about the requirement in the EYFS to liaise with other settings and professionals who might be involved in their child’s care and, as appropriate, I will – • Approach other settings / professionals to find out if and how they are prepared to work with me eg meetings, letters, telephone conversations, emails etc; • Provide other settings / professionals with details about the main themes, activities and celebrations children are involved with when they are with us; • Request meetings to discuss the child’s achievements and progress including sharing Learning Journeys; • Talk to children and their key person about what they enjoy doing at the other setting; • Complete information for other professionals or agencies on request; • Take an active interest in what the child does at the other setting and use the information to complement their learning and development experience. The kind of information I might share includes – • The name and date of birth of a child; • Behaviour concerns which are occurring across settings; • Emergency information which will be shared with my emergency care childminder; -

Quick, Timely Reads on the Waterfront

Quick, Timely Reads On the Waterfront Bugging State Street: An Erie Rite of Passage By David Frew July 2021 Dr. David Frew, a prolific writer, author, and speaker, grew up on Erie's lower west side as a proud "Bay Rat," joining neighborhood kids playing and marauding along the west bayfront. He has written for years about his beloved Presque Isle and his adventures on the Great Lakes. In this series, the JES Scholar-in-Residence takes note of life in and around the water. The 1950 Mercury was a popular artist’s pallet for the car crazies. Erie, Pennsylvania was not the only city where it happened. Teenagers in other towns had similar car-related customs. But the unique geography of the city made the popular pastime of driving up and down State Street in cars a special experience. During the 1950s, especially in the summer, hundreds of carloads of teens would find their way to State Street and begin a seemingly strange (to adults) nightly passage. Choosing one of three traditional entry portals, the cars would turn onto State Street either at 12th, 18th, or 26th streets and slowly descend the city’s main drag to the Public Dock (today’s Dobbins Landing). Almost seeking red lights, the perpetual parade of automobiles would crawl along, welcoming the opportunity to pause at each stoplight to rev engines and pop clutches. It was cool to “peel out” as you pulled away from a red light, even if there were just a few feet of space between you and the car ahead of you. -

Church Bulletin 2012

Saint Bernadette of Lourdes Parish “Where Miracles Happen” 1035 Turner Avenue Drexel Hill PA 19026 Phone: (610)789-7676 Fax: (610)789-9539 www.stbl.org March 11, 2018 — Fourth Sunday of Lent ____________________________________________________________________________ Mass Schedule Sunday Masses Holy Day Masses Saturday Vigil: 4:30pm Vigil Mass: 7:00pm — Holy Day: 8:30am Sunday: 7:00am, 9:00am and 11:00am Sunday (Summer): 8:00am and 10:00am Weekday Mass Sacrament of Reconciliation Monday—Thursday 8:30am Saturday: 3:30pm — 4:15pm Friday—4:00pm __________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Pastor Director of Religious Education Reverend Christopher J. Papa Marykate Murphy Resident School Principal Rev. Hugh J. Dougherty Mrs. Joanne Montie Weekend Assistant Parish Business Manager Reverend John T. Kelly, S.J. Robert J. Helmig Permanent Deacons Administrative Secretary Deacon Thomas P. Fitzpatrick Helen V. Kraus Deacon Michael J. Kubiak Parish Music Coordinator Deacon Francis B. Burke, Retired Dorothy Toomey 0234 Page Two March 11, 2018 FOURTH SUNDAY OF LENT Today, approximately halfway through Lent, we celebrate Laetare (“Rejoice”) Sunday. “Rejoice” is the first word of today’s entrance antiphon, and we rejoice because we know that the love God bears for us is stronger than any trials, hardships, or sufferings we may endure, even death. We know that the sacrifice that we are building toward holds the greatest victory imaginable: our salvation. Parish Information NEW FAMILIES VISITS TO THE MOST BLESSED SACRAMENT can be Welcome to St. Bernadette Parish! To register in the parish, made in the Chapel. please come to the rectory on Sunday mornings between 9:00am and 12:00noon. We are eager to greet new members of RECITATION OF THE ROSARY takes place every Monday our parish community and look forward to meeting you. -

Ufos in Fiction

UFOs in fiction Many works of fiction have featured UFOs. In most cases, as the fictional story progresses, the Earth is being invaded by hostile alien forces from outer space, usually from Mars, as depicted in early science fiction, or the people are being destroyed by alien forces, as depicted in the film Independence Day. Some fictional UFO encounters may be based on real UFO reports, such as Night Skies. Night Skies is based on the 1997 Phoenix UFO Incident. UFOs appear in many forms of fiction other than film, such as video games in the Destroy All Humans! or the X-COM series and Halo series and print, The War of the Worlds or Iriya no Sora, UFO no Natsu. Typically a small group of people or the military (which one depending on where the film was made), will fight off the invasion, however the monster Godzilla has fought against many UFOs. Books Oahspe: A New Bible - John Ballou Newbrough - First book to use the word Starship long before science-fiction writers conceived of interstellar space travel (1882). The War of the Worlds - H. G. Wells - Martian capsules are shot at Earth by aliens on This 1929 cover of Science Mars.(1898). Wonder Stories, drawn by Imaginary Friends (1967) - Alison Lurie - Two sociologists investigate a UFO cult. notable pulp artist Frank R. Saucer Wisdom (1999) - Rudy Rucker Paul, is one of the earliest The Unreals, a novel by Donald Jeffries (2007). depictions of a "flying saucer" in https://web.archive.org/web/20100115010803/http://donaldjeffries.com/ fiction Radio "War of the Worlds" a radio play by Orson Welles, caused all manner of panic in 1938 Contents Films Books Radio 1930s Films 1930s Flash Gordon - 1936 1940s Buck Rogers - 1939 - a.k.a.