Feature Sharing and (In)Definiteness in the Nominal Domain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. an Utterance Is Composed of a Sequence of Discrete Segments. Is the Segm

LINGUISTICS 221 Lecture #3 DISTINCTIVE FEATURES Part 1. An utterance is composed of a sequence of discrete segments. Is the segment indivisible? Is the segment the smallest unit of phonological analysis? If it is, segments ought to differ randomly from one another. Yet this is not true: pt k prs What is the relationship between members of the two groups? p t k - the members of this set have an internal relationship: they are all voiceles stops. p r s - no such relationship exists p b d s bilabial bilabial alveolar alveolar stop stop stop fricative voiceless voiced voiced voiceless SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES! Segments may be viewed as composed of sets of properties rather than indivisible entities. We can show the relationship by listing the properties of each segment. DISTINCTIVE FEATURES • enable us to describe the segments in the world’s languages: all segments in any language can be characterized in some unique combination of features • identifies groups of segments → natural segment classes: they play a role in phonological processes and constraints • distinctive features must be referred to in terms of phonetic -- articulatory or acoustic -- characteristics. 1 Requirements on distinctive feature systems (p. 66): • they must be capable of characterizing natural segment classes • they must be capable of describing all segmental contrasts in all languages • they should be definable in phonetic terms The features fulfill three functions: a. They are capable of describing the segment: a phonetic function b. They serve to differentiate lexical items: a phonological function c. They define natural segment classes: i.e. those segments which as a group undergo similar phonological processes. -

![Arxiv:2106.08037V1 [Cs.CL] 15 Jun 2021 Alternative Ways the World Could Be](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7624/arxiv-2106-08037v1-cs-cl-15-jun-2021-alternative-ways-the-world-could-be-357624.webp)

Arxiv:2106.08037V1 [Cs.CL] 15 Jun 2021 Alternative Ways the World Could Be

The Possible, the Plausible, and the Desirable: Event-Based Modality Detection for Language Processing Valentina Pyatkin∗ Shoval Sadde∗ Aynat Rubinstein Bar Ilan University Bar Ilan University Hebrew University of Jerusalem [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Paul Portner Reut Tsarfaty Georgetown University Bar Ilan University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (1) a. We presented a paper at ACL’19. Modality is the linguistic ability to describe b. We did not present a paper at ACL’20. events with added information such as how de- sirable, plausible, or feasible they are. Modal- The propositional content p =“present a paper at ity is important for many NLP downstream ACL’X” can be easily verified for sentences (1a)- tasks such as the detection of hedging, uncer- (1b) by looking up the proceedings of the confer- tainty, speculation, and more. Previous studies ence to (dis)prove the existence of the relevant pub- that address modality detection in NLP often p restrict modal expressions to a closed syntac- lication. The same proposition is still referred to tic class, and the modal sense labels are vastly in sentences (2a)–(2d), but now in each one, p is different across different studies, lacking an ac- described from a different perspective: cepted standard. Furthermore, these senses are often analyzed independently of the events that (2) a. We aim to present a paper at ACL’21. they modify. This work builds on the theoreti- b. We want to present a paper at ACL’21. cal foundations of the Georgetown Gradable Modal Expressions (GME) work by Rubin- c. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

The syntax of answers to negative yes/no-questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University 1. Introduction This paper will argue that answers to polar questions or yes/no-questions (YNQs) in English are elliptical expressions with basically the structure (1), where IP is identical to the LF of the IP of the question, containing a polarity variable with two possible values, affirmative or negative, which is assigned a value by the focused polarity expression. (1) yes/no Foc [IP ...x... ] The crucial data come from answers to negative questions. English turns out to have a fairly complicated system, with variation depending on which negation is used. The meaning of the answer yes in (2) is straightforward, affirming that John is coming. (2) Q(uestion): Isn’t John coming, too? A(nswer): Yes. (‘John is coming.’) In (3) (for speakers who accept this question as well formed), 1 the meaning of yes alone is indeterminate, and it is therefore not a felicitous answer in this context. The longer version is fine, affirming that John is coming. (3) Q: Isn’t John coming, either? A: a. #Yes. b. Yes, he is. In (4), there is variation regarding the interpretation of yes. Depending on the context it can be a confirmation of the negation in the question, meaning ‘John is not coming’. In other contexts it will be an infelicitous answer, as in (3). (4) Q: Is John not coming? A: a. Yes. (‘John is not coming.’) b. #Yes. In all three cases the (bare) answer no is unambiguous, meaning that John is not coming. -

Staged Approach for Grammatical Gender Identification of Nouns Using Association Rule

Staged Approach for Grammatical Gender Identification of Nouns using Association Rule Mining and Classification Shilpa Desai1, Jyoti Pawar1, and Pushpak Bhattacharyya2 1 Department of Computer Science and Technology Goa University, Goa - India [email protected], [email protected] 2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering IIT-Bombay, Mumbai - India [email protected] Abstract. In some languages, gender is a grammatical property of the noun. Grammatical gender identification enhances machine translation of such languages. This paper reports a three staged approach for gram- matical gender identification that makes use of word and morphological features only. A Morphological Analyzer is used to extract the morpho- logical features. In stage one, association rule mining is used to obtain grammatical gender identification rules. Classification is used at the sec- ond stage to identify grammatical gender for nouns that are not covered by grammatical gender identification rules obtained in stage one. The third stage combines the results of the two stages to identify the gender. The staged approach has a better precision, recall and F-score compared to machine learning classifiers used on complete data set. The approach was tested on Konkani nouns extracted from the Konkani WordNet and an F-Score 0.84 was obtained. 1 Introduction Gender is a grammatical property of nouns in many languages3 including Indian language such as Sanskrit, Hindi, Gujarati, Marathi and Konkani. In such lan- guages adjectives and verbs in a sentence agree with the gender of the noun. For example translation of \He is a good boy" and \She is a good girl" in Hindi is \vaha eka achchhaa laDakaa haai 4" and "vaha eka achchhii laDakii haai", respectively. -

Serial Verb Constructions: Argument Structural Uniformity and Event Structural Diversity

SERIAL VERB CONSTRUCTIONS: ARGUMENT STRUCTURAL UNIFORMITY AND EVENT STRUCTURAL DIVERSITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Melanie Owens November 2011 © 2011 by Melanie Rachel Owens. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/db406jt2949 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Beth Levin, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Joan Bresnan I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Vera Gribanov Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Abstract Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) are constructions which contain two or more verbs yet behave in every grammatical respect as if they contain only one. -

Inflection, P. 1

36607. MORPHOLOGY Prof. Yehuda N. Falk Inflection, p. 1 In flectional morphology expresses morphosyntactic properties of lexemes. For each lexical category (part of speech) there is a certain set of available properties; the forms specify the properties. The most straightforward way to model this is in terms of features and their vvvaluesvaluesalues. For nirkod expresses a particular set of properties associated נרקוד example, the Hebrew form with the lexeme RAKAD : the feature TENSE with the value FUTURE , the feature PERSON with the value 1, and the feature NUMBER with the value PLURAL . The textbook uses di Terent terminology: in flectional dimension instead of feature , and in flectional category instead of value . The term feature is also sometimes used for a feature-value combination, such as the phrase “the past tense feature”. The in flectional properties of a word can be represented as a fffeature-valuefeature-value (or attribute-valueattribute-value) representation: RAKAD TENSE FUT nirkod PERS 1 NUM PL This can also be written horizontally, and even abbreviated: 〈RAKAD , [ TENSE FUT , PERS 1, NUM PL ]〉 nirkod 1Pl.Fut A paradigm is a chart showing all the features and feature values for a particular lexeme. The expression of in flectional properties is called exponenceexponence. In the simplest case, there is a . זכרונות one-to-one relationship between properties and exponents. Note the word ZIKARON zixron+ot []NUM PL Zixron is the stem, and the su Ux -ot is the exponent of the [ NUM PL ] feature. טובות Not everything is that simple, though. Consider the adjective 36607. MORPHOLOGY Prof. Yehuda N. Falk Inflection, p. -

Proceedings of the IWCS 2013 Workshop on Annotation of Modal

Challenges in modality annotation in a Brazilian Portuguese Spontaneous Speech Corpus Luciana Beatriz Avila SecondHeliana Author Mello Second Author PosLin-UFMG/UFV/Capes AffiliationUFMG/FGV/CNPq / Address line 1 Affiliation / Address line 1 Av Antonio Carlos 6627 AffiliationAv Antonio / Address Carlos 6627line 2 Affiliation / Address line 2 Belo Horizonte, MG 31270-901 Brazil Belo Horizonte,Affiliation MG/ Address 31270 line-901 3 Brazil Affiliation / Address line 3 [email protected] heliana.melloemail@[email protected] email@domain category stands for, as well as identifying linguistic Abstract elements that carry it, is of utmost relevance. Our goal in annotating modality in a This short paper introduces the first notes about a modality annotation system that is under spontaneous speech Brazilian Portuguese Corpus is development for a spontaneous speech to provide a reliable starting point for researchers Brazilian Portuguese corpus (C-ORAL- that might be interested in developing BRASIL). We indicate our methodological methodologies associated to NLP that ensue the decisions, the points which seem to be well extraction of oral discourse reliability, certainty resolved and two issues for further discussion and factuality markers, or carrying sentiment and investigation. analysis, modeling modality and similar objectives. 3 Defining modality 1 Credits In this paper we study modality in a spontaneous The authors are thankful to CNPq, FAPEMIG and speech corpus, the C-ORAL-BRASIL, which will CAPES (Proc. nº BEX 9537/12-0) for research be presented in 4 below. As for spontaneous funding support. speech, we follow Cresti and Scarano (1998:5) in characterizing it as “the fulfillment of linguistic 2 Introduction acts, not programmed and not programmable, Modality annotation is inexistent for both written because they emerge during the unfolding of an and spoken Brazilian Portuguese corpora, thus the interaction, always new and unpredictable, novelty of this project. -

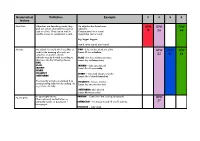

Grammatical Feature Definition Example 3 4

Grammatical Definition Example 3 4 5 6 feature Adjectives Adjectives are describing words; they An adjective has three forms: GfW GfW GfW pick out certain characteristics such as Adjective size or colour. They can be used to Comparative (-er or more) 10 26 44 modify a noun or complement a verb. Superlative (-est or most). big, bigger, biggest stupid, more stupid, most stupid Adverbs An adverb is a word which modifies or TIME – before, now, then, already, soon, seldom. GFW GfW GfW adds to the meaning of a verb, an Example: We have met before. adjective or another adverb. 23 39 44 Adverbs may be divided according to PLACE – here, there, everywhere and nowhere. their use, into the following classes: Example: They came here yesterday. TIME PLACE MANNER – badly, easily, slowly, well MANNER Example: The tall boy won easily. DEGREE FREQUENCY DEGREE – almost, much, only, quite, very, rather QUESTIONING Example: The old lady walked very slowly. The majority adverbs are formed from FREQUENCY - once, twice, sometimes corresponding adjectives by adding –ly, Example: Once, twice, three times a lady. e.g. brave - bravely QUESTIONING- where, when, how Example: When did you see him? An apostrophe shows: OMISSION – Come over ‘ere. (colloquial speech) Apostrophes GfW Either a place of omitted letters or contracted words, or possession – CONTRACTION – It’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to. 27 belonging to. POSSESSION – John’s ball. Grammatical Definition Example 3 4 5 6 feature Article Articles can be found in two forms. They Definite: the differentiate the importance attributed to a noun. -

Pragmatic Person Features in Pronominal and Clausal Speech Act Phrases Hailey Hyekyeong Ceong* Abstract. This Paper Proposes

2021. Proc Ling Soc Amer 6(1). 484–498. https://doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v6i1.4984. Pragmatic person features in pronominal and clausal speech act phrases Hailey Hyekyeong Ceong* Abstract. This paper proposes the necessity of pragmatic person features (Ritter and Wiltschko 2018) in pronominal and clausal speech act phrases in Korean, giving three main arguments for such necessity: (i) pragmatic person [ADDRESSEE] is needed for hearsay mye which expresses the meaning of you told me without the lexical verb of saying, (ii) pragmatic person [SPEAKER] is needed for the unequal distribution of first-person plural pronouns with exhortative ca ‘let us’, and (iii) pragmatic persons [SPEAKER], and [ADDRESSEE] are needed for the asymmetric distribution of a dative goal argument in secondhand exhortatives. Based on the compatibility and incompatibility of exhortative ca- and secondhand exhortative ca- mye clauses with a first-person pronoun (e.g., na ‘I’, ce ‘I’, wuli ‘we’, and cehuy ‘we’), I argue that pragmatic person features are needed in syntax to account for their distribution. Keywords. person; formality; clusivity; speech act phrases; hearsay; Korean 1. Introduction. This paper investigates pragmatic person features in pronominal and clausal speech act phrases focusing on the properties of first-and secondhand exhortatives in Korean. Based largely on evidence from a survey of variable pronominal paradigms across languages, Ritter and Wiltschko (2018) state that some languages lexicalize the distinction between prag- matic and grammatical person features. In this paper, I argue, on the basis of the distribution and interpretation of first-and secondhand exhortative markers, first-person pronouns, and the (dis-) agreement with the head of exhortatives and a first-person pronoun, that the distinction is lexical- ized in Korean as well. -

Introduction Chapter 5 Discusses Both Inflection and Derivation. It Also

1 Introduction Chapter 5 discusses both inflection and derivation. It also showcases two views on the distinction between the two. The first view is called the dichotomy approach. The second view is the continuum approach. Below the main points of the chapter will be summarized. Inflectional Values - Inflectional affixes are called inflectional values (or inflectional feature values). For example, English verbs uses the affix -ed to express the inflectional value ‘past’, as in walked. - It is worth-noting that the term ‘value’ is not used to describe derivational affixes. Instead, derivation is described in terms of derivational meanings. - The reason for the distinction between ‘values’ and ‘meanings’ is that while derivational affixes, such as -er in walker, have a meaning, inflectional affixes do not have a clear meaning. They only have syntactic functions. - Different languages depict different amounts of inflectional complexity. For example, English is poor of inflectional morphemes, compared to other languages like Spanish, French, Italian, German, and Arabic. There are also languages that have no inflectional affixes (e.g. Vietnamese and Igbo). - Inflectional values can be grouped together into super-categories. If two values share a functional property and cannot co-occur in the same context, they belong to the same feature. For example, English present and past are two values that belong to the same 2 feature, which is tense. If a sentence has the present value on its matrix verb, it will not have the past value on the same verb. - Other features can have several inflectional values. For example, case can have the following inflectional values: nominative, accusative, and genitive. -

On the Semantic Markedness of 舍-Features

On the Semantic Markedness of Φ-Features Uli Sauerland January 2005 When linguists talks about features, they usually talk about markedness as well. One reason is that feature systems are more efficient if there is an unmarked default value contrasted with a marked value. Nevertheless it is often difficult to determine which feature value should be regarded as the unmarked one. Φ-features are a particularly interesting case since they are important in many different domains of linguistic inquiry, and therefore markedness considerations arise in several different ways. To my knowledge, Greenberg (1966) was the first to investigate markedness in the domain of φ-features. He presents several tests from different domains for markedness. Later works (Noyer 1992, Harley & Ritter 2002), focus more narrowly on morphological markedness. My focus, however, is semantic markedness. One of Greenberg’s test for markedness, which I discuss below as Dominance, is semantic. I develop three other tests for semantic markedness. Using these tests, I then investigate the semantic markedness of person, number, and gender features. In the person domain, I conclude that there is clear evidence that third person 1 is featurally unmarked in all languages. I furthermore conclude that second person is semantically less marked than first person in English and other languages that lack the inclusive/exclusive distinction, while first and second person are equally marked in languages that have the distinction. In the number domain, I argue that the plural is unmarked in all languages. In languages that possess a dual, it seems furthermore that the dual is less marked than the singular, but not all tests are conclusive on this point.