Citrus – Tangelo Citrus × Tangelo J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 1

Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Lecture 32 Citrus Citrus: Citrus spp., Rutaceae Citrus are subtropical, evergreen plants originating in southeast Asia and the Malay archipelago but the precise origins are obscure. There are about 1600 species in the subfamily Aurantioideae. The tribe Citreae has 13 genera, most of which are graft and cross compatible with the genus Citrus. There are some tropical species (pomelo). All Citrus combined are the most important fruit crop next to grape. 1 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 The common features are a superior ovary on a raised disc, transparent (pellucid) dots on leaves, and the presence of aromatic oils in leaves and fruits. Citrus has increased in importance in the United States with the development of frozen concentrate which is much superior to canned citrus juice. Per-capita consumption in the US is extremely high. Citrus mitis (calamondin), a miniature orange, is widely grown as an ornamental house pot plant. History Citrus is first mentioned in Chinese literature in 2200 BCE. First citrus in Europe seems to have been the citron, a fruit which has religious significance in Jewish festivals. Mentioned in 310 BCE by Theophrastus. Lemons and limes and sour orange may have been mutations of the citron. The Romans grew sour orange and lemons in 50–100 CE; the first mention of sweet orange in Europe was made in 1400. Columbus brought citrus on his second voyage in 1493 and the first plantation started in Haiti. In 1565 the first citrus was brought to the US in Saint Augustine. 2 Tropical Horticulture: Lecture 32 Taxonomy Citrus classification based on morphology of mature fruit (e.g. -

'Orlando' Tangelos on 10 Rootstocks

Literature Cited Proc. Int. Soc. Citriculture. (In press) 3. Reece, P. C, and F. E. Gardner. 1959. Robinson, Osceola and Lee- 1. Hearn, C. J., P. C. Reece, and R. Fenton. 1968. Effects of pollen new early maturing tangerine hybrids. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. source on fruit characteristics and set of four citrus hybrids. Proc. 72:48-51. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 81:94-98. 4. , , and C. J. Hearn. 1963. Page orange—a prom 2. Krezdorn, A. H. 1977. Influence of rootstock on mandarin cultivars. ising variety. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 76:53-54. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 90:47-49. 1977. THE PERFORMANCE OF 'NOVA' AND 'ORLANDO' TANGELOS ON 10 ROOTSTOCKS D. J. Hutchison and C. J. Hearn1 The rootstocks were Carrizo (CAR), Rusk (RSK), and Agricultural Research Service, Troyer (TROY) citranges (C. sinensis (L.) Osbeck X U.S. Department of Agriculture, Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.); Estes rough lemon (RL) (C. Orlando, FL 32803 Union (L.) Burm. L); Milam (MIL) (rough lemon hybrid?); Seville sour orange (SO) (C. aurantium L.); Cleopatra mandarin (CLEO) (C. reticulata); Large Flower trifoliate Additional index words. Citrus. orange (LETO) (P. trifoliata); Orlando tangelo (ORL); and Sanguine Grosse Ronde sweet orange (SANG) (C. Abstract. 'Nova' and 'Orlando' tangelos were evaluated sinensis). on 10 rootstocks during 1968-1976. 'Nova' and 'Orlando' tangelos propagated on rough lemon rootstock produced the largest trees. The highest yields were 'Nova' on rough lemon Results and Discussion and 'Orlando' on Troyer rootstocks. The highest total soluble The time of bloom indicated by percentage petal drop solids were produced by 'Nova' on sour orange and 'Or in 1969 and 1971 is shown in Table 1. -

Tangerines, Mandarins, Satsumas, and Tangelos

Tangerines, Mandarins, Satsumas, and Tangelos Category: Semi-evergreen Hardiness: Damage will occur when temperatures drop below the low 20’s Fruit Family: Citrus Light: Full sun to half day sun Size: 10’H x 10’W; may be pruned to desired HxW Soil: Well-drained Planting: Plant after danger of frost has passed, mid to late March The name “tangerine” derives from one variety that was imported to Europe from Tangiers. There are many named varieties of what citrus growers call “mandarins” because of their Asian origins. One of these, the “Satsuma”, is an heirloom Japanese mandarin that is both delicious and especially adapted to Southeast Texas. It has been part of Gulf Coast Citrus history for a century. There are many named varieties of Satsumas. Mandarins are mostly orange-fleshed, juicy, highly productive, very easy to care for, long-lived, easily peeled and segmented or juiced. Few fruits can match the mandarin. Satsumas are seedless or close to seedless. They are all of outstanding quality and differ little among themselves except for when they ripen. Buy early, mid and late season varieties to have months of ripe fruit harvests from September to April. Care of Mandarins and related fruits Planting: Newly purchased citrus have probably not been hardened off to tolerate our winter weather. Keep your citrus in the container until late March, or until all danger of freeze has passed. Trees can be kept outside in a sunny area on mild days and nights, but move them into the shelter of the garage or house if frost is predicted. -

December HOTM Citrus

February's Harvest of the Month is... Citr u s The Wonderful World of Citrus Fruit While the orange is a favorite among citrus, there are many other unique varieties of citrus that you may not be as familiar with. See below for information about some lesser known varieties that might encourage students to try something new! Car a Car a Or ange Discovered in the m id-70s in Venezuela, the cara cara orange is a cross betw een the Washington navel and the Brazilian Bahia navel. The outside of this fruit looks like any other com m on navel, but opens up to beautiful pink flesh and a com plex, sw eet flavor, w ith hints of berries and roses. P om elo If you're not a grapefruit fan due to its bitter tang, then a pom elo m ay be just w hat you need. One of the largest citrus fruits, pom elos com e in a variety of colors, w ith their skin ranging from yellow to green and the flesh varying betw een pink and w hite. The taste is sim ilar to a grapefruit, though significantly sw eeter and lacking that distinct bitter bite. Tangelo Tangelos are the result of super-sw eet tangerines that have been crossbred w ith either a pom elo or a grapefruit. The result is a sw eet, easy-to-peel treat that has the color of a tangerine, but a m ore m ild sw eetness. You can tell a tangelo apart from an orange by its slight bell-shape and a sm all bum p w here the stem attached to the fruit. -

Caribbean Fruit Fly Host List

1 Caribbean Fruit Fly Host List Common Name Botanical Name Akee Blighia sapida Allspice Pimenta dioica Ambarella Spondias cytherea Atemoya Annona cherimola X A. squamosa Apple Malus sylvestris, Malus domestica Malus spp. Autumn Maple Tree Bischofia javanica Avocado, except commercial fruit Persea americana Balsam Apple Momordica balsamina Barbados Cherry Malpighia glabra Bell Pepper, except commercial fruit Capsicum frutescens, Capsicum annuum Birchberry Eugenia ligustrina Blackberry Rubus hybrid Box Orange Severinia buxifolia Brazil Cherry Eugenia dombeyi Cabeluda Plinia glomerata Calabur Muntingia calabura Calamondin X Citrofortunella mitis Carambola Averrhoa carambola Ceylon Gooseberry Dovyalis hebecarpa Cherry of the Rio Grande Eugenia aggregata Clementine Citrus reticulata Cocoplum Chrysolbalanus icaco Custard Apple, Sugar Apple Annona squamosa, Annona reticulata Egg Fruit Pouteria campechiana Date Palm Phoenix dactylifera Fig Ficus carica Garcinia aristata Garcinia aristata Garcinia Garcinia spp. Governor's Plum Flacourtia indica Grapefruit Citrus paradisi 2 Caribbean Fruit Fly Host List Grumichama Eugenia brasiliensis Guava (all) Psidium spp. Guiana Plum Drypetes lateriflora Hog Plum Spondias mombin Imbe Garcinia livingstonei Jaboticaba Myrciaria cauliflora Jack Orangequat Citrus nobilis 'unshu' x Fortunella sp. Jambolan Plum Syzygium cumini Jamboisier Rouge Eugenia pyriformis Cambess. var. uvalha Japanese Pear Pyrus pyrifolia Japanese Persimmon Diospyros kaki Java Apple Syzygium samarangense Kei Apple Dovyalis caffra Kieffer Pear -

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Presentation

New and Noteworthy Citrus Varieties Citrus species & Citrus Relatives Hundreds of varieties available. CITRON Citrus medica • The citron is believed to be one of the original kinds of citrus. • Trees are small and shrubby with an open growth habit. The new growth and flowers are flushed with purple and the trees are sensitive to frost. • Ethrog or Etrog citron is a variety of citron commonly used in the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles. The flesh is pale yellow and acidic, but not very juicy. The fruits hold well on the tree. The aromatic fruit is considerably larger than a lemon. • The yellow rind is glossy, thick and bumpy. Citron rind is traditionally candied for use in holiday fruitcake. Ethrog or Etrog citron CITRON Citrus medica • Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron is a unique citrus grown mainly as a curiosity. The six to twelve inch fruits are apically split into a varying number of segments that are reminiscent of a human hand. • The rind is yellow and highly fragrant at maturity. The interior of the fruit is solid rind with no flesh or seeds. • Fingered citron fruits usually mature in late fall to early winter and hold moderately well on the tree, but not as well as other citron varieties. Buddha’s Hand or Fingered citron NAVEL ORANGES Citrus sinensis • ‘Washington navel orange’ is also known • ‘Lane Late Navel’ was the first of a as the Bahia. It was imported into the number of late maturing Australian United States in 1870. navel orange bud sport selections of Washington navel imported into • These exceptionally delicious, seedless, California. -

Minneola Tangelo1 Larry K

HS171 Minneola Tangelo1 Larry K. Jackson and Stephen H. Futch2 The Minneola tangelo (Figure 1) is a Duncan grapefruit The fruit is usually fairly large, typically 3 - 3½ inches in x Dancy tangerine hybrid released in 1931 by the United diameter. The peel color is quite good and at peak maturity States Department of Agriculture Horticultural Research achieves a bright reddish-orange color. The peel is relatively Station in Orlando. This tangelo (like other tangelo culti- thin, smooth, and tends to adhere to the internal fruit vars) is therefore 1/2 tangerine and 1/2 grapefruit. The fruit surface. Seed numbers are few, but variable, and range is quite handsome and a genuine pleasure to eat. from 0 up to perhaps as many as 15 seeds per fruit. Fruit produced on trees in solid plantings of Minneola are likely to be seedless (or nearly so), while trees in mixed plantings will typically have 7-12 seeds due to the influence of cross- pollination. Minneola is not strongly self-fruitful and yields will be greater when interplanted with suitable pollenizing cultivars such as Temple, Sunburst, or possibly Fallglo. The fruit matures in the December-February period and has found ready acceptance in the gift fruit trade because of its handsome appearance and excellent eating quality. These same qualities have made Minneola a popular dooryard tree as well. Tree Characteristics Minneola trees are quite vigorous, and given adequate room to develop, will make large trees. They tend to be fairly Figure 1. Minneola tangelo. Credits: UF/IFAS CREC cold-hardy, ranking just below its sister cultivar, Orlando. -

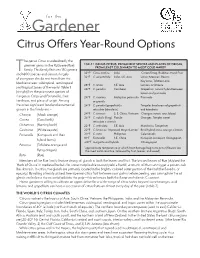

Citrus Offers Year-Round Options

for the Gardener Citrus Offers Year-Round Options he genus Citrus is undoubtedly the premier genus in the Rutaceae (Rue) TABLE 1. GENUS CITRUS: PROMINENT SPECIES AND PLACES OF ORIGIN, FROM LEAST COLD HARDY TO MOST COLD HARDY family. This family features 150 genera T 32ºF* Citrus medica India Citron/Etrog, Buddha’s Hand Fruit and 1600 species and consists largely 32ºF C. aurantiifolia India, S.E. Asia Limes: Mexican, Bearss, of evergreen shrubs and trees from the Key Lime, Tahitian Lime Mediterranean, subtropical, semitropical 28ºF C. limon S.E. Asia Lemons or limonia and tropical zones of the world. Table 1 26ºF C. paradisi Carribean Grapefruit: natural hybrid between (at right) lists the prominent species of lemon and pummelo the genus Citrus (and Fortunella), their 24ºF C. maxima Malaysian peninsula Pummelo hardiness, and place of origin. Among or grandis the other significant food and ornamental 24ºF C. paradisi (grapefruit) x Tangelo: bred cross of grapefruit genera in the family are – reticulata (Mandarin) and Mandarin Choisya (Mock orange) 24ºF C. sinensis S. E. China, Vietnam Oranges: sweet, sour, blood 24ºF C. nobilis (King) Florida Oranges: Temple, sweet Correa (Coral bells) reticulata x sinensis Dictamnus (Burning bush) 22ºF C. reticulata S.E. Asia Mandarins, Tangerines Casimiroa (White zapote) 22ºF C. limon cv. ‘Improved Meyer Lemon’ Bred hybrid cross, orange x lemon Fortunella (Kumquats and their 20ºF C. mitis Phillipines Calamondin 18ºF Fortunella S.E. China Kumquat, Limequat, Orangequat, hybrid forms) -20ºF margarita and hybrids Citrangequat Poncirus (Trifoliate orange and * approximate temperature at which frost damage begins to occur (flowers are flying dragon) the most cold-sensitive, followed by fruit, leaves, and wood) Ruta (Rue) Members of the Rue family feature strong oil glands in both the leaves and fruit. -

Application of Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequence Method for Analysis of Cytoplasmic Genome Among Aurantioideae Intergeneric Somatic Hybrids

J. AMER. SOC. HORT. SCI. 128(2):225–230. 2003. Application of Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequence Method for Analysis of Cytoplasmic Genome among Aurantioideae Intergeneric Somatic Hybrids Samia Lotfy1 CIRAD-FLHOR, Neufchâteau, 97 130, Capesterre Belle-Eau, Guadeloupe, France Francois Luro INRA, SRA San Giuliano, 20230 San Nicolao, France Françoise Carreel, Yann Froelicher, Delphine Rist, and Patrick Ollitrault CIRAD-FLHOR, Neufchâteau, 97 130, Capesterre Belle-Eau, Guadeloupe, France ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. cpDNA, mtDNA, protoplast fusion, Citrus breeding ABSTRACT. Somatic hybridization allows the creation of new patterns of nuclear, mitochondrial and chloroplastic association. It is therefore necessary to master cytoplasmic molecular markers to determine the genetic origin of both organelles of plantlets obtained from protoplasts fusion. In the case of Citrus and related genera, only southern blot hybridization and restriction fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP) techniques were used for this task until now. Here, we describe the use in the Aurantioideae subfamily, of a simple and non labeling cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) technique, to determine the cytoplasmic genome origin of intergeneric somatic hybrids. Mitochondrial and chloroplastic universal primers previously selected for population genetic studies in Quercus by Demesure et al. (1995) are used with some modifications. The variability of cytoplasmic genome among somatic fusion partners is detected by coupling amplification and restriction reactions. Digested -

Notices of Supplemental Proposed Rulemaking NOTICES of SUPPLEMENTAL PROPOSED RULEMAKING

Arizona Administrative Register Notices of Supplemental Proposed Rulemaking NOTICES OF SUPPLEMENTAL PROPOSED RULEMAKING After an agency has filed a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking with the Secretary of State’s Office for Register publication and the agency decides to make substantial changes to the rule after it is proposed, the agency must prepare a Notice of Supplemental Pro- posed Rulemaking for submission to the Office, and the Secretary of State shall publish the Notice under the Administrative Proce- dure Act (A.R.S. § 41-1001 et seq.). Publication of the Notice of Supplemental Proposed Rulemaking shall appear in the Register before holding any oral proceedings (A.R.S. § 41-1022). NOTICE OF SUPPLEMENTAL PROPOSED RULEMAKING TITLE 3. AGRICULTURE CHAPTER 4. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PLANT SERVICES DIVISION PREAMBLE 1. Register citation and date for the original Notice of Proposed Rulemaking: Notice of Proposed Rulemaking: 8 A.A.R. 4834, November 22, 2002 2. Sections Affected Rulemaking Action R3-4-239 Amend 3. The statutory authority for the rulemaking, including both the authorizing statute (general) and the statutes the rules are implementing (specific): Authorizing statute: A.R.S. § 3-107(A)(1) Implementing statutes: A.R.S. §§ 3-201.01 and 3-211 4. The name and address of agency personnel with whom persons may communicate regarding the rule: Name: Sherry D. Blatner, Rules Analyst Address: Arizona Department of Agriculture 1688 W. Adams, Room 235 Phoenix, AZ 85007 Telephone: (602) 542-0962 Fax: (602) 542-5420 E-mail: [email protected] 5. An explanation of the rule, including the agency’s reasons for initiating the rule: This rulemaking updates the areas under quarantine, removes the need for a receiver to apply for a compliance agree- ment to have an approved holding area, and clarifies existing language. -

Citrus Care for the Low Desert Residential Landscape Citrus Care for the Low Desert Residential Landscape 1

CITRUS CARE FOR THE LOW DESERT RESIDENTIAL LANDSCAPE CITRUS CARE FOR THE LOW DESERT RESIDENTIAL LANDSCAPE 1. Chose/Pick out the right tree. 2. Plant in the right place. 3. Plant correctly 4. Minimize pruning 5. Protect the trunk. 6. Fertilize and Irrigate properly 7. Protect from pests and frost Check Your County Crop Report Before You Buy/Plant your Crop 1. Farmers grow crops to make money and support themselves and their families. 2. Farmers pick crops adapted to their area because adjusting the climate/soil to help non-adapted plants thrive in a non-ideal location increases production costs and decreases profit. 3. Grow what your local farmers grow for best results. NOT ALL CITRUS THRIVE IN THE DESERT There are many varieties of citrus trees available, but not all of them do well in the desert. Furthermore, some of the Mandarins (Tangerines) and Tangelos need a different citrus pollinator tree to produce well. Following is a partial list of desert - compatible favorites. CITRUS FOR THE LOW DESERT The Grapefruits The Oranges The Mandarins (Tangerines) The Tangelos The Lemons The Limes The Kumquats Ruby Red Grapefruit Marsh Grapefruit Oroblanco CITRUS FOR THE LOW DESERT The Grapefruits The Oranges The Mandarins (Tangerines) The Tangelos The Lemons The Limes The Kumquats Eating Orange Hamlin Orange Valencia Orange VALENCIA (Juice) Oranges Olinda Campbell Blood Orange Blood Orange: Torocco Blood Orange: Mora CITRUS FOR THE LOW DESERT The Grapefruits The Oranges The Mandarins (Tangerines) The Tangelos The Lemons The Limes The Kumquats Alternate -

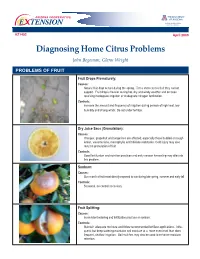

Diagnosing Home Citrus Problems John Begeman, Glenn Wright

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1492 April 2009 Diagnosing Home Citrus Problems John Begeman, Glenn Wright PROBLEMS OF FRUIT Fruit Drops Prematurely: Causes: Natural fruit drop occurs during the spring. Trees shed excess fruit they cannot support. Fruit drop is heavier during hot, dry and windy weather and on trees receiving inadequate irrigation or inadequate nitrogen fertilization. Controls: Increase the amount and frequency of irrigation during periods of high heat, low humidity and strong winds. Do not under fertilize. Dry Juice Sacs (Granulation): Causes: Oranges, grapefruit and tangerines are affected; especially those budded on rough lemon, volkameriana, macrophylla and trifoliate rootstocks. Cold injury may also result in granulation of fruit. Controls: Good fertilization and nutrition practices and early season harvesting may alleviate this problem. Sunburn: Causes: Sun scorch of fruit most directly exposed to sun during late spring, summer and early fall. Controls: Seasonal, no control necessary. Fruit Splitting: Causes: Inconsistent watering and fertilization practices or sunburn. Controls: Maintain adequate moisture and follow recommended fertilizer applications. Infre- quent, but deep watering maintains soil moisture at a more even level than does frequent, shallow irrigation. Soil mulches may also be used to enhance moisture retention. Thick Peel and Puffy, Misshapen Fruit: Causes: A natural response of young citrus to the heat and low humidity of the desert. Can be found on older citrus, especially grapefruit and oranges that have been over-fertilized. Controls: Follow recommended cultural practices. Reduce nitrogen fertilization rates. Holes: Causes: Birds, chewing insects, or rodents. Controls: Bird netting, fencing, and removal of rodent nests from trees. Insect damage of this type requires no control.