Appellants Brief -- Strickland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Occum Inciment Et Fugia Nobitas Ditate Quam Neurolaw

from SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012 Volume 24, Issue 5 A publication of the American Society of Trial Consultants Foundation Occum inciment et fugia nobitas ditate quam Neurolaw: Trial Tips for Today and Game Changing Questions for the Future By Alison Bennett HE FUTURE OF LAW is standing on the courthouse steps. cannot predict the point in time at which the intersection of Neurolaw – the combination of neuroscience research technology and law will merge to create credible courtroom Tand the law – is worthy of attention for a number of evidence, we can look to neurolaw research today for research reasons. Neuroscientists are conducting ground-breaking findings that confirm current trial practice techniques and research with a machine called a functional MRI, or fMRI, offer new insights into jury decision making and the art of which is similar to traditional MRI technology but focuses on persuasion. brain activity, not just structure. Some would argue the use of neuroscientific evidence based on fMRI research is a premature Current Criminal Trial Applications adoption of a novel technology, but neurolaw evidence is already In the United States, neuroscientific evidence has been influencing jury trials in the United States and abroad. Billions admitted in over one hundred criminal trials now, has been of dollars are being pored into interdisciplinary neuroscience cited in at least one U. S. Supreme Court case, and is being research each year in the United States and abroad. While we admitted as evidence in other countries as well. In many cases, September/October 2012 - Volume 24, Issue 5 thejuryexpert.com 1 neuroscientific evidence was offered to mitigate sentencing “John grasped the object” and “Pablo kicked the ball.” by presenting neuroimaging highlighting brain damage that The scans revealed activity in the motor cortex, which could have diminished the perpetrator’s capacity and ability coordinates the body’s movements, indicating imagining to make rational decisions. -

Supreme Court of the United States

no reactions indicative of deception. Htr. 44. Smith also testified that he was aware Davenport suffered a stroke sometime prior to 2006, did not have any record associated with the polygraph, and was now unavailable to answer questions about his conduct of the exam. Htr. 184-85. Smith also obtained two affidavits from Britt; one was executed on October 26,2005, the other in November 2005. Htr. 44-52; DX 5058; DX 5059. The October affidavit stated, in at least one paragraph, that Britt transported Stoeckley from Charleston to Raleigh; the November affidavit states that he transported her from Greenville to Raleigh. DX 5058 f 15; DX 5059 ^ 15; see also Htr. 40 (“Sometimes he said Charleston. Sometimes he said Greenville.”). The October affidavit also mentions what Britt felt was unethical behavior - Judge Dupree accepting cakes made by jurors - during the MacDonald trial. DX 5058 U 28. In February 2006, Britt executed an addendum to his affidavit, which included more detail than his previous affidavits. Htr. 199; GX 2089.34 Specifically, Britt stated that he and Holden transported Stoeckley to the courthouse on August 15,1979, for her interviews with the parties. GX 2089. He also stated that the defense interview of Stoeckley concluded around noon, and he then escorted her to the U.S. Attorney’s office. Britt again asserted that he was present during Stoeckley’s interview with the Government, and quoted Blackburn as telling her: “If you go downstairs and testify that you were at Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald’s house on the night of the murders, I will indict you as an accessory to murder.” Id. -

Neurolaw Or Frankenlaw? the Thought Police Have Arrived Brain

Volume 16, Issue 1 Summer 2011 Neurolaw or Frankenlaw? Brain-Friendly The Thought Police Have Arrived Case Stories By Larry Dossey, MD Part Two Reprinted with the author’s permission “This technology . opens up for the first time the possibility of punishing By Eric Oliver people for their thoughts rather than their actions.” —Henry T. Greely, bioethicist, Stanford Law School Without the aid of trained emotions the intellect is powerless against the animal organism.” Wonder Woman, the fabulous comic book heroine, wields a formidable - C. S. Lewis weapon called the Lasso of Truth. This magical lariat makes it impossible for anyone caught in it to lie. FIRST THINGS FIRST American psychologist William Moulton Marston created Wonder After the August, 1974 resig- Woman in 1941. He hit a nerve; Wonder Woman has been the most popular nation of Richard Nixon, an apoc- Continued on pg. 32 ryphal story began making the media rounds. It seems one of the major outlets had run a simple poll, asking respondents who they had voted for in the previous presi- dential race: McGovern or Nixon. have a most productive and practical contribution According to the results, Nixon had to share with you from my friend and consulting lost to “President” McGovern by a colleague, Amy Pardieck, from Perceptual Litigation. No stranger to these pages, Katherine James, landslide! Whether it is true or not, of ACT of Communication, makes the case that ac- the story rings of verisimilitude. Hi All – tors and directors have known for decades what tri- What the pollsters didn’t measure, Welcome to the second issue of the new al attorneys interested in bridging the gap between and which would have been much Mental Edge. -

The Potential Contribution of Neuroscience to the Criminal Justice System of New Zealand

1 The Potential Contribution of Neuroscience to the CriminalJustice System of New Zealand SARAH MURPHY I INTRODUCTION Descriptions of "neurolaw", the legal discipline governing the intersection of law and neuroscience, span a continuum from "contribut[ing] nothing more than new details"' to ushering in "the greatest intellectual catastrophe in the history of our species". This controversy is not unwarranted. The "technological wizardry"3 of modern neuroscience tracks the movement of fluids and electrical currents, revealing both structure and organic functioning, and is the closest humans have come to "mind reading". While not unwarranted, the controversy's reactionary nature gives the misleading impression that neurolaw is a modem invention. In fact, neurolaw's historical roots are evident in the law's foundational preoccupation with concepts of mens rea and moral desert.' Connections between criminal behaviour and brain injury appeared as early as 1848,1 with biological positivism making formal - and sinister - progress at the end of the 19th century.6 Current legal applications of neuroscience both continue this story and reflect a wider trend of science gaining popular trust and interest from the courts.' Such applications have been proposed t Winner of the 2011 Minter Ellison Rudd Watts Prize for Legal Writing. * BSc (Biological Sciences)/LLB(Hons). The author would like to thank Professor Warren Brookbanks of the University of Auckland Faculty of Law, for his advice during the writing of this dissertation and an earlier, related research paper. I Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen "For the law, neuroscience changes nothing and everything" (2004) 359 Phil Trans R Soc Lond B 1775 at 1775. -

Mccormick on Evidence and the Concept of Hearsay: a Critical Analysis Followed by Suggestions to Law Teachers Roger C

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1981 McCormick on Evidence and the Concept of Hearsay: A Critical Analysis Followed by Suggestions to Law Teachers Roger C. Park UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation Roger C. Park, McCormick on Evidence and the Concept of Hearsay: A Critical Analysis Followed by Suggestions to Law Teachers, 65 Minn. L. Rev. 423 (1981). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/598 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Park Roger Author: Roger C. Park Source: Minnesota Law Review Citation: 65 Minn. L. Rev. 423 (1981). Title: McCormick on Evidence and the Concept of Hearsay: A Critical Analysis Followed by Suggestions to Law Teachers Originally published in MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW. This article is reprinted with permission from MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW and University of Minnesota Law School. McCormick on Evidence and the Concept of Hearsay: A Critical Analysis Followed by Suggestions to Law Teachers Roger C. Park* Few modern one volume treatises are as widely used or as influential as McCormick's Handbook of the Law of Evidence.1 The book has been employed by teachers as a casebook substi- tute in law school evidence courses,2 used by attorneys in the practice of law, and cited extensively by the Advisory Commit- tee on the Federal Rules of Evidence.3 McCormick deserves the popularity that it has achieved as a teaching tool and a ref- erence work. -

Expert Witnesses

Law 101: Legal Guide for the Forensic Expert This course is provided free of charge and is designed to give a comprehensive discussion of recommended practices for the forensic expert to follow when preparing for and testifying in court. Find this course live, online at: https://law101.training.nij.gov Updated: September 8, 2011 DNA I N I T I A T I V E www.DNA.gov About this Course This PDF file has been created from the free, self-paced online course “Law 101: Legal Guide for the Forensic Expert.” To take this course online, visit https://law101.training. nij.gov. If you already are registered for any course on DNA.gov, you may logon directly at http://law101.dna.gov. Questions? If you have any questions about this file or any of the courses or content on DNA.gov, visit us online at http://www.dna.gov/more/contactus/. Links in this File Most courses from DNA.Gov contain animations, videos, downloadable documents and/ or links to other userful Web sites. If you are using a printed, paper version of this course, you will not have access to those features. If you are viewing the course as a PDF file online, you may be able to use these features if you are connected to the Internet. Animations, Audio and Video. Throughout this course, there may be links to animation, audio or video files. To listen to or view these files, you need to be connected to the Internet and have the requisite plug-in applications installed on your computer. -

Qarinah: Admissibility of Circumstantial Evidence in Hudud and Qisas Cases

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 2 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy March 2015 Qarinah: Admissibility of Circumstantial Evidence in Hudud and Qisas Cases Mohd Munzil bin Muhamad Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia [email protected] Ahmad Azam Mohd Shariff Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia [email protected] Ramalinggam Rajamanickam Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia [email protected] Mazupi Abdul Rahman Senior Assistant Commissioner, Polis DiRaja Malaysia [email protected] Anowar Zahid Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia [email protected] Noorfajri Ismail Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n2p141 Abstract Two recent developments in Brunei and Malaysia on hudud and qisas implementation have revived the keen discussion and debate on admissibility of qarinah. The Brunei monarch has already approved the hudud, qisas and ta’zir implementation and a special committee has already been set up to look into several substantive, procedural and administrative matters. In Malaysia, the Kelantan government is currently looking into some preliminary matters regarding hudud, qisas and ta’zir application in view of the recent Federal Government’s green light on the said syariah criminal law application. The said state government is already in the midst of engaging itself into important discussions with other relevant authorities on the said matter. In view of these two recent developments, this paper strives at analyzing the issue of qarinah admissibility in hudud and qisas cases. Attempt is also made in identifying some misconceptions on the said issue while coming up with some analytical response on dispelling the misconceptions. -

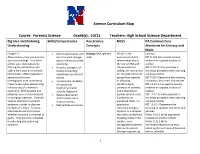

Science Curriculum Map Course: Forensic Science Grade(S): 10/11

Science Curriculum Map Course: Forensic Science Grade(s): 10/11 Teachers: High School Science Department Big Idea and Enduring Skills/Competencies Key Science NGSS PA Common Core Understanding Concepts Standards for Literacy and Math Chapter 1: Define observation, and Biology: DNA, genetic HS-LS3-1 Ask Literacy: Observation is how you perceive describe what changes code questions to clarify RST.9-10.1 Cite specific textual your surroundings. Your brain occur in the brain while relationships about evidence to support analysis of affects your observations by observing. the role of DNA and science. filtering the information you Describe examples of chromosomes in RST.9-10.3 Follow precisely a take in from your environment. factors influencing coding the instructions multistep procedure when carrying Many factors affect eyewitness eyewitness accounts of for characteristic traits out experiments accounts of a crime. events. passed from parents RST.9-10.4 Determine the meaning Investigators must understand Compare the reliability to offspring. of symbols, key terms and phrases. these factors when determining of eyewitness HS-LS3-3 Apply RST.11-12.1 Cite specific textual the accuracy of a witness’s testimony to what concepts of statistics evidence to support analysis of testimony. With practice and actually happened. and probability to science. patience, you can train yourself Relate observation explain variation and RST.11-12.3 Follow precisely a to be a good observer. Forensic skills to their use in distribution of multistep procedure when carrying Science attempts to uncover forensic science. expressed traits in a out experiments. evidence in order to discover Define forensic science population. -

Res Ipsa Loquitur: Reducing Confusion of Creating Bias?

Penn State Law eLibrary Journal Articles Faculty Works 2020 Res Ipsa Loquitur: Reducing Confusion of Creating Bias? John E. Lopatka Jeffrey Kahn Follow this and additional works at: https://elibrary.law.psu.edu/fac_works Part of the Torts Commons RES IPSA LoQuITuR: REDUCING CONFUSION OR CREATING BIAS? Jeffrey H. Kahn' & John E. Lopatka"' ABSTRACT The so-called doctrine of res ipsa loquitur has been a mystery since its birth more than a century ago. This Article helps solve the mystery. In practicaleffect, res ipsa loquitur, though usually thought ofas a tort doctrine, functions as a rule of trialpractice that allows jurors to rely upon circumstantialevidence surroundingan accident to find the defendant liable. Standardjuryinstructions in negligence cases, however, informjurors that they are permitted to rely upon circumstantialevidence in reachinga verdict. Why, then, is another, more specific circumstantialevidence charge necessary or desirable? We describe and evaluate the arguments that have been made in support of and in opposition to the res ipsa instruction. One theory is thatjurors are confused in performing their task when given only standardinstructions; the charge, therefore, clarifies their task, thereby improving the quality of their decisionmaking. A competing theory is that the instructionbiases jurors infavor ofplaintiffs, thereby degrading the quality of decisionmaking. Our theoretical analysis concludes that the bias explanation is stronger. We reach this conclusion by applying for the first-time modern learning on cognition to the res ipsa instruction. To support our theoretical conclusion, we report the results of experiments designed to determine the effects of the instruction. All these experiments were intendedfirst to confirm that the res ipsa instruction has an effect and second to confirm or refute our theoretical conclusion that the instruction biases rather than clarifies. -

Veasey V. Abbott

No. 14-41127 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT _______________________ MARC VEASEY; JANE HAMILTON; SERGIO DELEON; FLOYD CARRIER; ANNA BURNS; MICHAEL MONTEZ; PENNY POPE; OSCAR ORTIZ; KOBY OZIAS; LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN CITIZENS; JOHN MELLOR-CRUMLEY, Plaintiffs-Appellees TEXAS ASSOCIATION OF HISPANIC COUNTY JUDGES AND COUNTY COMMISSIONERS, Intervenor Plaintiffs-Appellees v. GREG ABBOTT, in his Official Capacity as Governor of Texas; TEXAS SECRETARY OF STATE; STATE OF TEXAS; STEVE MCCRAW, in his Official Capacity as Director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, Defendants-Appellants (See inside cover for continuation of caption) _______________________ ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS _______________________ BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS APPELLEE _______________________ KENNETH MAGIDSON VANITA GUPTA United States Attorney Acting Assistant Attorney General Southern District of Texas JOHN ALBERT SMITH, III DIANA K. FLYNN Office of the U.S. Attorney ERIN H. FLYNN 800 Shoreline Blvd., Ste. 500 CHRISTINE A. MONTA Corpus Christi, TX 78401 Attorneys Department of Justice Civil Rights Division Appellate Section Ben Franklin Station P.O. Box 14403 Washington, DC 20044-4403 (202) 514-2195 (Continuation of caption) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee TEXAS LEAGUE OF YOUNG VOTERS EDUCATION FUND; IMANI CLARK, Intervenor Plaintiffs-Appellees v. STATE OF TEXAS; TEXAS SECRETARY OF STATE; STEVE MCCRAW, in his Official Capacity as Director of the Texas Department -

Volume III: Forensic Evidence at Murder Trials in Phoenix, Arizona

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Volume III: Forensic Evidence at Murder Trials in Phoenix, Arizona Author(s): Tom McEwen, Ph.D., Edward Connors Document No.: 244482 Date Received: December 2013 Award Number: 2004-DD-BX-1466 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant report available electronically. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Institute for Law and Justice 1018 Duke Street Alexandria, Virginia Phone: 703-684-5300 Volume III Forensic Evidence at Murder Trials in Phoenix, Arizona Final Report July 2009 Prepared by Tom McEwen, PhD Edward Connors Prepared for National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs U. S. Department of Justice This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Table of Contents Chapter 1: Forensic Evidence at Trials ............................................................................................1 Background ................................................................................................................................1 -

Circumstantial Evidence in Arson Cases William C

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 41 | Issue 2 Article 16 1950 Circumstantial Evidence in Arson Cases William C. Braun Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation William C. Braun, Circumstantial Evidence in Arson Cases, 41 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 226 (1950-1951) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CIRCUMSTANTIAL EVIDENCE IN ARSON CASES William C. Braun William C. Braun is the Chief Special Agent, National Board of Fire Under- writers, Chicago, and since 1947 has been in charge of the Arson Division of their midwest territory. As a graduate (LL. B.) of National University Law School, Washington, D. C., he has been admitted to the bar of Washington, D. C., Wyoming, and Georgia. From 1927-30 he was a Special Agent of the F.B.I., and then until 1947 a Special Agent of the National Board of Fire Underwriters, St. Paul, Minn. This article was presented last May at the Sixth Annual Arson Investigators' Seminar and Training Course, Purdue University, for which course Mr. Braun serves as a member of the Advisory and Planning Committee. He is a member of the International Association of Arson Investigators and has lectured on arson at a number of- Regional Fire Training Schools.-EnrTOR.