A Unique Role for Stat5 in Recovery from Acute Anemia Gregory D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oncostatin M Exhibit Elevated Responsiveness to IL-31 Receptor

IL-31 Receptor (IL-31RA) Knockout Mice Exhibit Elevated Responsiveness to Oncostatin M This information is current as Janine Bilsborough, Sherri Mudri, Eric Chadwick, Brandon of September 28, 2021. Harder and Stacey R. Dillon J Immunol 2010; 185:6023-6030; Prepublished online 18 October 2010; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902769 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/185/10/6023 Downloaded from References This article cites 29 articles, 6 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/185/10/6023.full#ref-list-1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on September 28, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2010 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology IL-31 Receptor (IL-31RA) Knockout Mice Exhibit Elevated Responsiveness to Oncostatin M Janine Bilsborough,1 Sherri Mudri,1 Eric Chadwick,2 Brandon Harder,3 and Stacey R. Dillon IL-31 signals through the heterodimeric receptor IL-31RA and oncostatin M receptor (OSMR), and has been linked with the development of atopic dermatitis, a Th2 cytokine-associated disease in humans. -

Respiratory Viral Infection Function for Innate Defense Against Airway Epithelial Versus Immune Cell Stat1

Airway Epithelial versus Immune Cell Stat1 Function for Innate Defense against Respiratory Viral Infection This information is current as Laurie P. Shornick, Audrey G. Wells, Yong Zhang, Anand of September 27, 2021. C. Patel, Guangming Huang, Kazutaka Takami, Moises Sosa, Nikhil A. Shukla, Eugene Agapov and Michael J. Holtzman J Immunol 2008; 180:3319-3328; ; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3319 Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/180/5/3319 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2008/02/20/180.5.3319.DC1 Material http://www.jimmunol.org/ References This article cites 47 articles, 20 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/180/5/3319.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision by guest on September 27, 2021 • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2008 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. The Journal of Immunology Airway Epithelial versus Immune Cell Stat1 Function for Innate Defense against Respiratory Viral Infection1 Laurie P. -

Oncostatin M Is a Proinflammatory Mediator. in Vivo Effects Correlate with Endothelial Cell Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines and Adhesion Molecules

Oncostatin M is a proinflammatory mediator. In vivo effects correlate with endothelial cell expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules. V Modur, … , G A Zimmerman, T M McIntyre J Clin Invest. 1997;100(1):158-168. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI119508. Research Article Oncostatin M is a member of the IL-6 family of cytokines that is primarily known for its effects on cell growth. Endothelial cells have an abundance of receptors for oncostatin M, and may be its primary target. We determined if oncostatin M induces a key endothelial cell function, initiation of the inflammatory response. We found that subcutaneous injection of oncostatin M in mice caused an acute inflammatory reaction. Oncostatin M in vitro stimulated: (a) polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) transmigration through confluent monolayers of primary human endothelial cells; (b) biphasic PMN adhesion through rapid P-selectin expression, and delayed adhesion mediated by E-selectin synthesis; (c) intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 accumulation; and (d) the expression of PMN activators IL-6, epithelial neutrophil activating peptide-78, growth-related cytokine alpha and growth-related cytokine beta without concomitant IL-8 synthesis. The nature of the response to oncostatin M varied with concentration, suggesting high and low affinity oncostatin M receptors independently stimulated specific responses. Immunohistochemistry showed that macrophage-like cells infiltrating human aortic aneurysms expressed oncostatin M, so it is present during a chronic inflammatory reaction. Therefore, oncostatin M, but not other IL-6 family members, fulfills Koch's postulates as an inflammatory mediator. Since its effects on endothelial cells differ significantly from established mediators like TNFalpha, it may uniquely contribute to the inflammatory cycle. -

Potential Target Genes (Whole List)

Potential target genes (whole list) 1. MGC3200 hypothetical protein MGC3200, LocusLink=84265 2. FLJ20277 hypothetical protein FLJ20277, LocusLink=55624 3. POU2F1 POU domain, class 2, transcription factor 1, LocusLink=5451 4. EFNA3 ephrin-A3, LocusLink=1944 5. OAZ3 ornithine decarboxylase antizyme 3, LocusLink=51686 6. FLJ20139 hypothetical protein FLJ20139, LocusLink=54833 7. ARHC ras homolog gene family, member C, LocusLink=389 8. CRABP2 cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 2, LocusLink=1382 9. SIAT6 sialyltransferase 6 (N-acetyllacosaminide alpha 2,3-sialyltransferase) 10. FLJ13181 hypothetical protein FLJ13181, LocusLink=80263 11. TNFRSF14 tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 14 (herpesvirus entry mediator); 12. NUF2R hypothetical protein NUF2R, LocusLink=83540 13. PTAFR platelet-activating factor receptor, LocusLink=5724 14. LOC57147 hypothetical protein LOC57147, LocusLink=57147 15. GFI1 growth factor independent 1, LocusLink=2672 16. FLJ11220 hypothetical protein FLJ11220, LocusLink=54665 17. KIAA0673 KIAA0673 protein, LocusLink=23128 18. FLJ23323 hypothetical protein FLJ23323, LocusLink=79707 19. CEZANNE zinc finger protein Cezanne, LocusLink=56957 20. KIAA0736 KIAA0736 gene product, LocusLink=9900 21. KIAA0761 Mid-1-related chloride channel 1, LocusLink=23155 22. DD96 epithelial protein up-regulated in carcinoma, membrane associated protein 17 23. DDOST dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide-protein glycosyltransferase, LocusLink=1 24. FLJ10349 hypothetical protein FLJ10349, LocusLink=54707 25. FLJ12455 hypothetical protein FLJ12455, LocusLink=63906 26. DKFZP564D0478 hypothetical protein DKFZp564D0478, LocusLink=84065 27. NCF2 neutrophil cytosolic factor 2 (65kD, chronic granulomatous disease, autosomal 2) 28. AP4B1 adaptor-related protein complex 4, beta 1 subunit, LocusLink=10717 29. ASML3B acid sphingomyelinase-like phosphodiesterase, LocusLink=27293 30. CLASPIN homolog of Xenopus Claspin, LocusLink=63967 31. FLJ20435 hypothetical protein FLJ20435, LocusLink=54933 32. -

Molecular Signatures Differentiate Immune States in Type 1 Diabetes Families

Page 1 of 65 Diabetes Molecular signatures differentiate immune states in Type 1 diabetes families Yi-Guang Chen1, Susanne M. Cabrera1, Shuang Jia1, Mary L. Kaldunski1, Joanna Kramer1, Sami Cheong2, Rhonda Geoffrey1, Mark F. Roethle1, Jeffrey E. Woodliff3, Carla J. Greenbaum4, Xujing Wang5, and Martin J. Hessner1 1The Max McGee National Research Center for Juvenile Diabetes, Children's Research Institute of Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, and Department of Pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA. 2The Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 53211, USA. 3Flow Cytometry & Cell Separation Facility, Bindley Bioscience Center, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA. 4Diabetes Research Program, Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, WA, 98101, USA. 5Systems Biology Center, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20824, USA. Corresponding author: Martin J. Hessner, Ph.D., The Department of Pediatrics, The Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA Tel: 011-1-414-955-4496; Fax: 011-1-414-955-6663; E-mail: [email protected]. Running title: Innate Inflammation in T1D Families Word count: 3999 Number of Tables: 1 Number of Figures: 7 1 For Peer Review Only Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online April 23, 2014 Diabetes Page 2 of 65 ABSTRACT Mechanisms associated with Type 1 diabetes (T1D) development remain incompletely defined. Employing a sensitive array-based bioassay where patient plasma is used to induce transcriptional responses in healthy leukocytes, we previously reported disease-specific, partially IL-1 dependent, signatures associated with pre and recent onset (RO) T1D relative to unrelated healthy controls (uHC). -

Diverse Gene Expression and DNA Methylation Profiles Correlate with Differential Adaptation of Breast Cancer Cells to the Antiestrogens Tamoxifen and Fulvestrant

Research Article Diverse Gene Expression and DNA Methylation Profiles Correlate with Differential Adaptation of Breast Cancer Cells to the Antiestrogens Tamoxifen and Fulvestrant Meiyun Fan,1 Pearlly S. Yan,2 Cori Hartman-Frey,1 Lei Chen,1 Henry Paik,1 Samuel L. Oyer,1 Jonathan D. Salisbury,1 Alfred S.L. Cheng,2 Lang Li,3 Phillip H. Abbosh,1 Tim H-M. Huang,2 and Kenneth P. Nephew1,4,5 1Medical Sciences, Indiana University School of Medicine, Bloomington, Indiana; 2Division of Human Cancer Genetics, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; 3Division of Biostatistics, Department of Medicine and 4Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology, Indiana University School of Medicine; and 5Indiana University Cancer Center, Indianapolis, Indiana Abstract Introduction The development of targeted therapies for antiestrogen- The steroid hormone estrogen is strongly implicated in the resistant breast cancer requires a detailed understanding development and progression of breast cancer (1). The primary of its molecular characteristics. To further elucidate the mediator of estrogen action in breast cancer cells is estrogen molecular events underlying acquired resistance to the receptor a (ERa), a ligand-activated transcription factor (1). antiestrogens tamoxifen and fulvestrant, we established Consequently, the leading drugs used for endocrine therapy of drug-resistant sublines from a single colony of hormone- breast cancer all block ERa activity, including antiestrogens (i.e., dependent breast cancer MCF7 cells. These model systems tamoxifen and fulvestrant) and aromatase inhibitors (2). Despite allowed us to examine the cellular and molecular changes the efficacy and favorable safety profile of these agents, the use of induced by antiestrogens in the context of a uniform clonal endocrine therapy is limited by the onset of drug resistance, in background. -

ID AKI Vs Control Fold Change P Value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In

ID AKI vs control P value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In case of multiple probesets per gene, one with the highest fold change was selected. Fold Change 208083_s_at 7.88 0.000932 ITGB6 integrin, beta 6 202376_at 6.12 0.000518 SERPINA3 serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (alpha-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 3 1553575_at 5.62 0.0033 MT-ND6 NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 6 (complex I) 212768_s_at 5.50 0.000896 OLFM4 olfactomedin 4 206157_at 5.26 0.00177 PTX3 pentraxin 3, long 212531_at 4.26 0.00405 LCN2 lipocalin 2 215646_s_at 4.13 0.00408 VCAN versican 202018_s_at 4.12 0.0318 LTF lactotransferrin 203021_at 4.05 0.0129 SLPI secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor 222486_s_at 4.03 0.000329 ADAMTS1 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 1552439_s_at 3.82 0.000714 MEGF11 multiple EGF-like-domains 11 210602_s_at 3.74 0.000408 CDH6 cadherin 6, type 2, K-cadherin (fetal kidney) 229947_at 3.62 0.00843 PI15 peptidase inhibitor 15 204006_s_at 3.39 0.00241 FCGR3A Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIIa, receptor (CD16a) 202238_s_at 3.29 0.00492 NNMT nicotinamide N-methyltransferase 202917_s_at 3.20 0.00369 S100A8 S100 calcium binding protein A8 215223_s_at 3.17 0.000516 SOD2 superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial 204627_s_at 3.04 0.00619 ITGB3 integrin, beta 3 (platelet glycoprotein IIIa, antigen CD61) 223217_s_at 2.99 0.00397 NFKBIZ nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, zeta 231067_s_at 2.97 0.00681 AKAP12 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 12 224917_at 2.94 0.00256 VMP1/ mir-21likely ortholog -

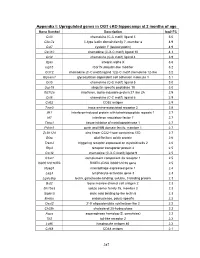

PDF (Appendices)

Appendix I: Upregulated genes in OGT cKO hippocampi at 2 months of age Gene Symbol Description log2 FC Ccl3 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 5.0 Clec7a C-type lectin domain family 7, member a 4.9 Cst7 cystatin F (leukocystatin) 4.9 Cxcl10 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 4.3 Ccl4 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 3.9 Itgax integrin alpha X 3.6 Isg15 ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier 3.2 Ccl12 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 12|c-C motif chemokine 12-like 3.2 Glycam1 glycosylation dependent cell adhesion molecule 1 3.1 Ccl5 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 3.0 Usp18 ubiquitin specific peptidase 18 3.0 Ifi27l2a interferon, alpha-inducible protein 27 like 2A 2.9 Ccl6 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 6 2.9 Cd52 CD52 antigen 2.9 Taar3 trace amine-associated receptor 3 2.8 Ifit1 interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 2.7 Irf7 interferon regulatory factor 7 2.7 Timp1 tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 2.7 Pyhin1 pyrin and HIN domain family, member 1 2.7 Zc3h12d zinc finger CCCH type containing 12D 2.7 Gfap glial fibrillary acidic protein 2.6 Trem2 triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 2.6 Rtp4 receptor transporter protein 4 2.5 Cxcl9 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 2.5 C3ar1 complement component 3a receptor 1 2.5 I830012O16Rik RIKEN cDNA I830012O16 gene 2.5 Mpeg1 macrophage expressed gene 1 2.4 Lag3 lymphocyte-activation gene 3 2.3 Lgals3bp lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 3 binding protein 2.3 Bst2 bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 2.3 Slc15a3 solute carrier family 15, member 3 2.3 Siglec5 sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin 5 2.3 Endou endonuclease, polyU-specific 2.2 Oasl2 2'-5' oligoadenylate synthetase-like 2 2.2 Ch25h cholesterol 25-hydroxylase 2.2 Aspg asparaginase homolog (S. -

Oncostatin M Induces Growth Arrest of Mammary Epithelium Via a CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein ␦-Dependent Pathway1

Vol. 1, 601–610, June 2002 Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 601 Oncostatin M Induces Growth Arrest of Mammary Epithelium via a CCAAT/enhancer-binding Protein ␦-dependent Pathway1 Julie A. Hutt and James W. DeWille2 These cytokines signal by binding to cell surface receptors, Department of Veterinary Biosciences [J. A. H., J. W. D.] and Division of which consist of cytokine-specific binding subunits and a Molecular Biology and Cancer Genetics, Ohio State Comprehensive common signaling subunit, glycoprotein 130 (2, 3). OSM is Cancer Center [J. W. D.], The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 43210 produced by a variety of cell types, including neoplastic breast epithelial cells (4). Other IL-6-type cytokines are also produced by normal and neoplastic breast epithelium and Abstract breast adipose cells (4). Furthermore, the IL-6 expression Oncostatin M (OSM), an interleukin 6-type cytokine, level in some types of mammary carcinoma is inversely cor- induces sustained up-regulation of CCAAT/enhancer- related with the histological grade of malignancy (5, 6). binding protein (C/EBP) ␦ mRNA and protein in OSM stimulates proliferation of some cell types, such as nonneoplastic HC11 mouse mammary epithelial cells. myeloma cells and Kaposi’s sarcoma cells, and inhibits pro- This up-regulation is dependent on signaling by liferation of others, such as melanoma cells and normal and phospho-Stat3 (signal transducers and activators of neoplastic mammary epithelial cells (7–12). In normal and transcription). The same signaling pathway is activated neoplastic human mammary epithelial cells, OSM inhibits cell in two human breast cancer cell lines, a neoplastic cycle progression, with a reduction in the proportion of S- mouse mammary epithelial cell line and a second phase cells and an adoption of morphological phenotype nonneoplastic mouse mammary epithelial cell line. -

Analyzing the Genomic and Transcriptomic Architecture of Milk

Guan et al. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology (2020) 11:35 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-020-00435-4 RESEARCH Open Access Analyzing the genomic and transcriptomic architecture of milk traits in Murciano- Granadina goats Dailu Guan1, Vincenzo Landi2, María Gracia Luigi-Sierra1, Juan Vicente Delgado2, Xavier Such3, Anna Castelló1,3, Betlem Cabrera1,3, Emilio Mármol-Sánchez1, Javier Fernández-Alvarez4, José Luis Ruiz de la Torre Casañas5, Amparo Martínez2, Jordi Jordana3 and Marcel Amills1,3* Abstract Background: In this study, we aimed to investigate the molecular basis of lactation as well as to identify the genetic factors that influence milk yield and composition in goats. To achieve these two goals, we have analyzed how the mRNA profile of the mammary gland changes in seven Murciano-Granadina goats at each of three different time points, i.e. 78 d (T1, early lactation), 216 d (T2, late lactation) and 285 d (T3, dry period) after parturition. Moreover, we have performed a genome-wide association study (GWAS) for seven dairy traits recorded in the 1st lactation of 822 Murciano-Granadina goats. Results: The expression profiles of the mammary gland in the early (T1) and late (T2) lactation were quite similar (42 differentially expressed genes), while strong transcriptomic differences (more than one thousand differentially expressed genes) were observed between the lactating (T1/T2) and non-lactating (T3) mammary glands. A large number of differentially expressed genes were involved in pathways related with the biosynthesis of amino acids, cholesterol, triglycerides and steroids as well as with glycerophospholipid metabolism, adipocytokine signaling, lipid binding, regulation of ion transmembrane transport, calcium ion binding, metalloendopeptidase activity and complement and coagulation cascades. -

Mediated Oncogenic Capacities in Colorectal Cancer

Supplemental Material includes three Supplemental Tables Identification of the Effects of Aspirin and Sulindac Sulfide on the Inhibition of HMGA2- Mediated Oncogenic Capacities in Colorectal Cancer Titus Ime Ekanem 1,2,†, Wei-Lun Tsai 3,†, Yi-Hsuan Lin 4, Wan-Qian Tan 3, Hsin-Yi Chang 5, Tsui-Chin Huang 3,6, Hsin-Yi Chen 3,6,* and Kuen-Haur Lee 3,6,7,8,* 1 Ph.D. Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University and Academia Sinica, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 Department of Hematology, University of Uyo, Uyo 520271, Nigeria 3 Graduate Institute of Cancer Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] (W.L.T.); [email protected] (W.Q.T.); [email protected] (T.C.H.) 4 Nutrition and Health Sciences, College of Nutrition, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] 5 Graduate Institute of Metabolism and Obesity Sciences, College of Nutrition, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, 11031, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Ph.D. Program for Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan 7 TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan 8 Cancer Center, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University 11696, Taipei, Taiwan * Correspondence:[email protected] (H.Y.C.); [email protected] (K.H.L.); -

TNFRSF14 Deficiency Protects Against Ovariectomy-Induced Adipose

E-K CHOI, W-K KIM and others Role of TNFRSF14 in CD11c 220:1 25–33 Research expression TNFRSF14 deficiency protects against ovariectomy-induced adipose tissue inflammation Eun-Kyung Choi*, Woon-Ki Kim*, Ok-Joo Sul, Yun-Kyung Park, Eun-Sook Kim1, Jae-Hee Suh2, Rina Yu3 and Hye-Seon Choi Department of Biological Sciences, University of Ulsan, Ulsan 680-749, Korea Correspondence 1Department of Endocrinology, Ulsan University Hospital, Ulsan 682-714, Korea should be addressed 2Department of Pathology, Ulsan University Hospital, Ulsan 682-714, Korea to H-S Choi 3Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Ulsan, Ulsan 680-749, Korea Email *(E-K Choi and W-K Kim contributed equally to this work) [email protected] Abstract To elucidate the role of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 14 (TNFRSF14) in Key Words metabolic disturbance due to loss of ovarian function, ovariectomy (OVX) was performed in " adipose tissue TNFRSF 14-knockout mice. OVX increased fat mass and infiltration of highly inflammatory " inflammatory diseases CD11c cells in the adipose tissue (AT), which was analyzed by flow cytometry, and resulted in " ovarian function disturbance of glucose metabolism, whereas TNFRSF14 deficiency attenuated these effects. " menopause TNFRSF14 deficiency decreased recruitment of CD11c-expressing cells in AT and reduced the " glucose metabolism polarization of bone marrow-derived macrophages to M1. Upon engagement of LIGHT, a TNFRSF14 ligand, TNFRSF14 enhanced the expression of CD11c via generation of reactive Journal of Endocrinology oxygen species, suggesting a role of TNFRSF14 as a redox modulator. TNFRSF14 participated in OVX-induced AT inflammation via upregulation of CD11c, resulting in metabolic perturbation.