Degas/Cassatt, by Kimberly A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (PDF)

EDUCATOR GUIDE SCHEDULE EDUCATOR OPEN HOUSE Friday, September 28, 4–6pm | Jepson Center TABLE OF CONTENTS LECTURE Schedule 2 Thursday, September 27, 6pm TO Visiting the Museum 2 Members only | Jepson Center MONET Museum Manners 3 French Impressionism About the Exhibition 4 VISITING THE MUSEUM PLAN YOUR TRIP About the Artist 5 Schedule your guided tour three weeks Claude Monet 6–8 in advance and notify us of any changes MATISSE Jean-François Raffaëlli 9–10 or cancellations. Call Abigail Stevens, Sept. 28, 2018 – Feb. 10, 2019 School & Docent Program Coordinator, at Maximilien Luce 11–12 912.790.8827 to book a tour. Mary Cassatt 13–14 Admission is $5 each student per site, and we Camille Pissarro 15–16 allow one free teacher or adult chaperone per every 10 students. Additional adults are $5.50 Edgar Degas 17–19 per site. Connections to Telfair Museums’ Use this resource to engage students in pre- Permanent Collection 20–22 and post-lessons! We find that students get Key Terms 22 the most out of their museum experience if they know what to expect and revisit the Suggested Resources 23 material again. For information on school tours please visit https://www.telfair.org/school-tours/. MEMBERSHIP It pays to join! Visit telfair.org/membership for more information. As an educator, you are eligible for a special membership rate. For $40, an educator membership includes the following: n Unlimited free admission to Telfair Museums’ three sites for one year (Telfair Academy, Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters, Jepson Center) n Invitations to special events and lectures n Discounted rates for art classes (for all ages) and summer camps n 10 percent discount at Telfair Stores n Eligibility to join museum member groups n A one-time use guest pass 2 MUSEUM MANNERS Address museum manners before you leave school. -

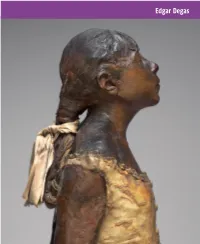

Edgar Degas French, 1834–1917 Woman Arranging Her Hair Ca

Edgar Degas French, 1834–1917 Woman Arranging her Hair ca. 1892, cast 1924 Bronze McNay Art Museum, Mary and Sylvan Lang Collection, 1975.61 In this bronze sculpture, Edgar Degas presents a nude woman, her body leaned forward and face obscured as she styles her hair. The composition of the figure is similar to those found in his paintings of women bathing. The artist displays a greater interest in the curves of the body and actions of the model than in capturing her personality or identity. More so than his posed representations of dancers, the nude served throughout Degas’ life as a subject for exploring new ideas and styles. French Moderns McNay labels_separate format.indd 1 2/27/2017 11:18:51 AM Fernand Léger French, 1881–1955 The Orange Vase 1946 Oil on canvas McNay Art Museum, Gift of Mary and Sylvan Lang, 1972.43 Using bold colors and strong black outlines, Fernand Léger includes in this still life an orange vase and an abstracted bowl of fruit. A leaf floats between the two, but all other elements, including the background, are abstracted beyond recognition. Léger created the painting later in his life when his interests shifted toward more figurative and simplified forms. He abandoned Cubism as well as Tubism, his iconic style that explored cylindrical forms and mechanization, though strong shapes and a similar color palette remained. French Moderns McNay labels_separate format.indd 2 2/27/2017 11:18:51 AM Pablo Picasso Spanish, 1881–1973 Reclining Woman 1932 Oil on canvas McNay Art Museum, Jeanne and Irving Mathews Collection, 2011.181 The languid and curvaceous form of a nude woman painted in soft purples and greens dominates this canvas. -

Timeline Mary Cassatt Cassatt & Degas

Mary Cassatt a biography Timeline Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born in 1844 in Allegheny City (now The artist’s focus on the lives of women, often depicted in their homes Pittsburgh), Pennsylvania. Although she was the American daughter of engaged in intellectual activities such as reading a book or newspaper, an elite Philadelphia family, she spent much of her childhood and later demonstrates a commitment to portraying them with rich inner 1840 life in France. Between 1860 and 1862, she studied at the Pennsylvania experiences, which was distinct from their roles as wives and mothers. Academy of Fine Arts. In Paris, she received classical artistic training As a female artist, she offered a unique insight into the private lives of 1844 Mary Stevenson Cassatt was born under the tutelage of the great Academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme women, particularly in the upper class, and she lends significance to their (1824–1904), learning to paint by recreating the works of the Old domestic world. on May 22 in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania Masters. When she was 24, one of her paintings, The Mandolin Player Cassatt was also an influential advisor to American art collectors. was accepted to be shown at the 1868 Paris Salon, which was the official Her social position as the daughter of a prominent Philadelphia family exhibition of the Academy of Fine Arts. Due to the outbreak of the connected her to many upper class patrons, and she convinced friends, Franco-Prussian War two years later, the artist left Europe for a brief most notably Louisine Elder Havemeyer (1855–1929), to buy the work hiatus in Philadelphia. -

Playing with Space

Edgar Degas Edgar Degas, Four Dancers, c. 1899, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection Edgar Degas, Self-Portrait Off Stage (Edgar Degas, par lui-même) (detail), probably 1857, etching, Degas made more than a thousand drawings, paintings, National Gallery of Art, Rosen- 2 wald Collection and sculptures on ballet themes. Most of his works do not show the dancers performing onstage. Instead, they are absorbed in their daily routine of rehearsing, stretching, and resting. Degas admired the ballerinas’ The Artist at the Ballet work — how they practiced the same moves over and over again to perfect them — and likened it to his 1 Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917) lived in Paris, the capital and approach as an artist. largest city in France, during an exciting period in the nineteenth century. In this vibrant center of art, music, Four Dancers depicts a moment backstage, just before and theater, Degas attended ballet performances as often the curtain rises and a ballet performance begins. The as he could. At the Paris Opéra, he watched both grand dancers’ red-orange costumes stand out against the productions on stage and small ballet classes in rehearsal green scenery. Short, quick strokes of yellow and white studios. He filled numerous notebooks with sketches paint on their arms and tutus catch light and, along to help him remember details. Later, he referred to his with squiggly black lines around the bodices, convey sketches to compose paintings and model sculpture he the dancers’ excitement as they await their cues to made in his studio. His penetrating observations of ballet go onstage. -

Edgar Degas: a Strange New Beauty, Cited on P

Degas A Strange New Beauty Jodi Hauptman With essays by Carol Armstrong, Jonas Beyer, Kathryn Brown, Karl Buchberg and Laura Neufeld, Hollis Clayson, Jill DeVonyar, Samantha Friedman, Richard Kendall, Stephanie O’Rourke, Raisa Rexer, and Kimberly Schenck The Museum of Modern Art, New York Contents Published in conjunction with the exhibition Copyright credits for certain illustrations are 6 Foreword Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty, cited on p. 239. All rights reserved at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 7 Acknowledgments March 26–July 24, 2016, Library of Congress Control Number: organized by Jodi Hauptman, Senior Curator, 2015960601 Department of Drawings and Prints, with ISBN: 978-1-63345-005-9 12 Introduction Richard Kendall Jodi Hauptman Published by The Museum of Modern Art Lead sponsor of the exhibition is 11 West 53 Street 20 An Anarchist in Art: Degas and the Monotype The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation. New York, New York 10019 www.moma.org Richard Kendall Major support is provided by the Robert Lehman Foundation and by Distributed in the United States and Canada 36 Degas in the Dark Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III. by ARTBOOK | D.A.P., New York 155 Sixth Avenue, 2nd floor, New York, NY Carol Armstrong Generous funding is provided by 10013 Dian Woodner. www.artbook.com 46 Indelible Ink: Degas’s Methods and Materials This exhibition is supported by an indemnity Distributed outside the United States and Karl Buchberg and Laura Neufeld from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Canada by Thames & Hudson ltd Humanities. 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX 54 Plates www.thamesandhudson.com Additional support is provided by the MoMA Annual Exhibition Fund. -

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM

DOMESTIC LIFE and SURROUNDINGS: IMPRESSIONISM: (Degas, Cassatt, Morisot, and Caillebotte) IMPRESSIONISM: Online Links: Edgar Degas – Wikipedia Degas' Bellelli Family - The Independent Degas's Bellelli Family - Smarthistory Video Mary Cassatt - Wikipedia Mary Cassatt's Coiffure – Smarthistory Cassatt's Coiffure - National Gallery in Washington, DC Caillebotte's Man at his Bath - Smarthistory video Edgar Degas (1834-1917) was born into a rich aristocratic family and, until he was in his 40s, was not obliged to sell his work in order to live. He entered the Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1855 and spent time in Italy making copies of the works of the great Renaissance masters, acquiring a technical skill that was equal to theirs. Edgar Degas. The Bellelli Family, 1858-60, oil on canvas In this early, life-size group portrait, Degas displays his lifelong fascination with human relationships and his profound sense of human character. In this case, it is the tense domestic situation of his Aunt Laure’s family that serves as his subject. Apart from the aunt’s hand, which is placed limply on her daughter’s shoulder, Degas shows no physical contact between members of the family. The atmosphere is cold and austere. Gennaro, Baron Bellelli, is shown turned toward his family, but he is seated in a corner with his back to the viewer and seems isolated from the other family members. He had been exiled from Naples because of his political activities. Laure Bellelli stares off into the middle distance, significantly refusing to meet the glance of her husband, who is positioned on the opposite side of the painting. -

Press Release

Press Contacts Cara Egan PRESS Seattle Art Museum P.R. [email protected] 206.748.9285 RELEASE Wendy Malloy Seattle Art Museum P.R. [email protected] JULY 2015 206.654.3151 INTIMATE IMPRESSIONISM FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART OPENS AT THE SEATTLE ART MUSEUM OCT 1, 2015 October 1, 2015–January 10, 2016 SEATTLE, WA – Seattle Art Museum (SAM) presents Intimate Impressionism from the National Gallery of Art, featuring the captivating work of 19th-century painters such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh. The exhibition includes 71 paintings from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and features a selection of intimately scaled Impressionist and Post-Impressionist still lifes, portraits and landscapes, whose charm and fluency invite close scrutiny. “This important exhibition is comprised of extraordinary paintings, among the jewels of one of the finest collections of French Impressionism in the world,” says Kimerly Rorschach, Seattle Art Museum’s Illsley Ball Nordstrom Director and CEO. “We are pleased to host these national treasures and provide our audience with the opportunity to enjoy works by Impressionist masters that are rarely seen in Seattle.” Seattle is the last opportunity to view this exhibition following an international tour that included Ara Pacis Museum of the Capitoline Museums, Rome; Fine Arts Museums in San Francisco; McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, and Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo. The significance of this exhibition is grounded in the high quality of each example and in the works’ variety of subject matter. The paintings’ dimensions reflect their intended function: display in domestic interiors. -

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism National Gallery of Art Teacher Institute 2014

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism National Gallery of Art Teacher Institute 2014 Painters of Modern Life in the City Of Light: Manet and the Impressionists Elizabeth Tebow Haussmann and the Second Empire’s New City Edouard Manet, Concert in the Tuilleries, 1862, oil on canvas, National Gallery, London Edouard Manet, The Railway, 1873, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art Photographs of Baron Haussmann and Napoleon III a)Napoleon Receives Rulers and Illustrious Visitors To the Exposition Universelle, 1867, b)Poster for the Exposition Universelle Félix Thorigny, Paris Improvements (3 prints of drawings), ca. 1867 Place de l’Etoile and the Champs-Elysées Claude Monet, Boulevard des Capucines, Paris, 1873, oil on canvas, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Great Boulevards, 1875, oil on canvas, Philadelphia Museum of Art Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Pont Neuf, 1872, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Collection Hippolyte Jouvin, The Pont Neuf, Paris, 1860-65, albumen stereograph Gustave Caillebotte, a) Paris: A Rainy Day, 1877, oil on canvas, Art Institute of Chicago, b) Un Balcon, 1880, Musée D’Orsay, Paris Edouard Manet, Le Balcon, 1868-69, oil on canvas, Musée D’Orsay, Paris Edouard Manet, The World’s Fair of 1867, 1867, oil on canvas, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo (insert: Daumier, Nadar in a Hot Air Balloon, 1863, lithograph) Baudelaire, Zola, Manet and the Modern Outlook a) Nadar, Charles Baudelaire, 1855, b) Contantin Guys, Two Grisettes, pen and brown ink, graphite and watercolor, Metropolitan -

Pène Du Bois, Guy American, 1884 - 1958

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Pène du Bois, Guy American, 1884 - 1958 Paul Juley, Guy Pène du Bois Standing in Front of "The Battery", 1936, photograph, Peter A. Juley & Son Collection, Smithsonian American Art Museum BIOGRAPHY Guy Pène du Bois was a noted art critic as well as a painter of pointed, sometimes witty, scenes of modern social interactions. Pène du Bois was born in Brooklyn, New York, on January 4, 1884. His father, Henri Pène du Bois, a journalist and writer of Louisiana Creole heritage, passed down his admiration of French language and culture to his son. Pène du Bois attended the New York School of Art from 1899 to 1905, where he studied first with William Merritt Chase (American, 1849 - 1916) and later Robert Henri (American, 1865 - 1929). Pène du Bois’s fellow pupils included George Bellows (American, 1882 - 1925), Rockwell Kent (American, 1882 - 1971), and Edward Hopper (American, 1882 - 1967). Hopper and Pène du Bois remained close friends throughout their careers. In 1905 he went to Paris with his father and briefly studied at the Academie Colarossi and took lessons from Théophile Alexandre Steinlen (Swiss, 1859 - 1923). He first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1905. Pène Du Bois’s work reflects a close observation of modern Parisian life in subjects such as men and women interacting in public spaces like cafés. He drew inspiration from contemporary French artists like Edgar Degas (French, 1834 - 1917) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864 - 1901). Du Bois and his father were forced to return to New York in 1906 after the elder Pène du Bois fell ill, but he died before they arrived. -

Mary S. Cassatt, the Childâ•Žs Bath

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Lake Forest College Publications Inter-Text: An Undergraduate Journal for Social Sciences and Humanities Volume 1 Article 4 2018 Mary S. Cassatt, The hiC ld’s Bath Eliska Mrackova Lake Forest College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://publications.lakeforest.edu/inter-text Recommended Citation Mrackova, Eliska (2018) "Mary S. Cassatt, The hiC ld’s Bath," Inter-Text: An Undergraduate Journal for Social Sciences and Humanities: Vol. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://publications.lakeforest.edu/inter-text/vol1/iss1/4 This Student Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Lake Forest College Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inter-Text: An Undergraduate Journal for Social Sciences and Humanities by an authorized editor of Lake Forest College Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mrackova: Mary S. Cassatt, The Child’s Bath Mary S. Cassatt, The Child’s Bath [ E M ] ary Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath (1893, oil on canvas, 39 ½ x 26 M inches) was one of a few paintings created by a female artist that was ever exhibited together with other Impressionist masterpieces painted by Manet, Monet, or Degas. The Child’s Bath illustrates an intimate scene between a mother and her young daughter inside a contemporary Parisian bedroom. Mary Cassatt was born in the United States in 1844 but spent most of her adult life in France, where she was infl uenced by her close friend Edgar Degas, advances in photography, as well as widely popular woodblock prints from Tokugawa, Japan. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 27, 2013

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 27, 2013 MEDIA CONTACT Emily Kowalski | (919) 664-6795 | [email protected] Masterworks from the Chrysler Museum on Loan to the N.C. Museum of Art Works to be installed in NCMA permanent collection galleries to inspire dialogue, enhance visitors’ experience Raleigh, N.C. — Beginning April 9, 2013, the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) will present paintings and sculptures from the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia. Selected by NCMA Curator of European Art David Steel, these 18th- and 19th-century works by such masters as Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Mary Cassatt, and Auguste Rodin will be installed among related works in the NCMA’s permanent collection. The works will be on display until February 2, 2014. “We are excited to partner with the Chrysler Museum to bring these extraordinary works of art to North Carolina,” says Lawrence J. Wheeler, director of the North Carolina Museum of Art. “Our mission has always been to provide access to the best works of art in the world. These magnificent loans help us to meet this noble goal while bringing to each visitor a rich experience with our own esteemed permanent collection.” The loans are being made available to the NCMA while the Chrysler Museum undergoes renovations. Steel selected an array of art that complemented the NCMA’s permanent collection. “It gradually dawned on me that the works I was giving the most thought to either perfectly complemented works in our collection, like the two masterpieces by Rodin (one of them a marble), or filled gaps we might never fill,” he says of his selection process. -

LET's LOOK the BALLET CLASS Edgar

THE BALLET CLASS Edgar Degas once said, “No art was ever less spontaneous than mine. A picture is an artificial work, outside nature. It calls for as much cunning as the commission of a crime.” Yet this painting almost seems spontaneous—Degas has captured young ballerinas of the Paris opera house at their most natural, when they are practicing 1880 Oil on canvas unselfconsciously behind the scenes, not performing for the public. 32 3/8 x 30 1/4 inches (82.2 x 76.8 cm) The Ballet Class is full of such paradoxes, or contradictions. Framed: 41 9/16 x 39 5/8 x 2 5/8 inches (105.6 x 100.6 x 6.7 cm) We typically think of ballerinas as glamorous and inherently grace- HILAIRE-GERMAIN- EDGAR DEGAS ful. Yet all five of these dancers are shown in awkward poses. In fact, French one of the dancers toward the back of the painting—the one trying Purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund, 1937, W1937-2-1 to balance on the toe of her shoe—is about to fall over! Another dancer, on the right side and toward the front, is looking downward LET’S LOOK as if checking the placement of her legs and feet. And in front of Who are the people in this them all, partially blocking our view, is an ordinary woman slumped painting? How can you tell? How many are there? Do any in a chair, reading the newspaper. We can’t help but wonder why the of them look similar? artist decided to put her there.