“Barriers to Female Entrepreneurship in Tajikistan” Micronarrative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

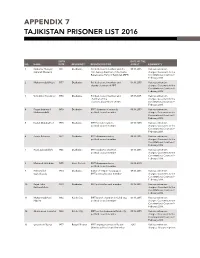

Appendix 7 Tajikistan Prisoner List 2016

APPENDIX 7 TAJIKISTAN PRISONER LIST 2016 BIRTH DATE OF THE NO. NAME DATE RESIDENCY RESPONSIBILITIES ARREST COMMENTS 1 Saidumar Huseyini 1961 Dushanbe Political council member and the 09.16.2015 Various extremism (Umarali Khusaini) first deputy chairman of the Islamic charges. Case went to the Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 2 Muhammadalii Hayit 1957 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.16.2015 Various extremism deputy chairman of IRPT charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 3 Vohidkhon Kosidinov 1956 Dushanbe Political council member and 09.17.2015 Various extremism chairman of the charges. Case went to the elections department of IRPT Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 4 Fayzmuhammad 1959 Dushanbe IRPT chairman of research, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Muhammadalii political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 5 Davlat Abdukahhori 1975 Dushanbe IRPT foreign relations, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 6 Zarafo Rahmoni 1972 Dushanbe IRPT chairman advisor, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 7 Rozik Zubaydullohi 1946 Dushanbe IRPT academic chairman, 09.16.2015 Various extremism political council member charges. Case went to the Constitutional Court on 9 February 2016. 8 Mahmud Jaloliddini 1955 Hisor District IRPT chairman advisor, 02.10.2015 political council member 9 Hikmatulloh 1950 Dushanbe Editor of “Najot” newspaper, 09.16.2015 Various extremism Sayfullozoda IRPT political council member charges. -

Formative Research on Infant and Young Child Feeding

FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING Final Report AND MATERNAL NUTRITION 2016 IN TAJIKISTAN Conducted by Dornsife School of Public Health & College of Nursing and Health Professions, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA USA For UNICEF Tajikistan Under Drexel’s Long Term Agreement for Services In Communication for Development (C4D) with UNICEF And Contract # 43192550 January 11 through November 30, 2016 Principal Investigator Ann C Klassen, PhD , Professor, Department of Community Health and Prevention Co-Investigators Brandy Joe Milliron PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Beth Leonberg, MA, MS, RD – Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences Graduate Research Staff Lisa Bossert, MPH, Margaret Chenault, MS, Suzanne Grossman, MSc, Jalal Maqsood, MD Professional Translation Staff Rauf Abduzhalilov, Shokhin Asadov, Malika Iskandari, Muhiddin Tojiev This research is conducted with the financial support of the Government of the Russian Federation Appendices : (Available Separately) Additional Bibliography Data Collector Training, Dushanbe, March, 2016 Data Collection Instruments Drexel Presentations at National Nutrition Forum, Dushanbe, July, 2016 cover page photo © mromanyuk/2014 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1: Executive Summary 5 Section 2: Overview of Project 12 Section 3: Review of the Literature 65 Section 4: Field Work Report 75 Section 4a: Methods 86 Section 4b: Results 101 Section 5: Conclusions and Recommendations 120 Section 6: Literature Cited 138 FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING FORMATIVE RESEARCH ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING 3 AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN AND MATERNAL NUTRITION IN TAJIKISTAN SECTION 1: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Tajikistan is a mountainous, primarily rural country of approximately 8 million residents in Central Asia. -

RGP O2 Eval Report Final.Pdf

! ! Evaluation Output 2 Rural Growth Programme UNDP Republic of Tajikistan Evaluation Report Kris B. Prasada Rao Alisher Khaydarov Aug 2013 ! ! ! List%of%acronyms,%terminology%and%currency%exchange%rates% Acronyms AFT Aid for Trade AKF Aga Khan Foundation AO Area Office BEE Business Enabling Environment CDP Community Development Plan CO Country Office CP Communities Programme DCC Tajikistan Development Coordination Council DDP District Development Plan DFID Department for International Development DIM Direct Implementation Modality DP Development Plan GDP Gross Domestic Product GIZ Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GREAT Growth in the Rural Economy and Agriculture of Tajikistan HDI Human Development Index ICST Institute for Civil Servants Training IFC International Finance Corporation, the World Bank IOM International Organisation for Migration JDP Jamoat Development Plan LED Local Economic Development LEPI Local Economic Performance Indicator M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MEDT Ministry of Economic Development and Trade MC Mahalla Committee MoF Ministry of Finance MoU Memorandum of Understanding MSDSP Mountain Societies Development Support Programme MSME Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise NDS National Development Strategy NIM National Implementation Modality O2 Output 2, RGP O&M Operation and Maintenance ODP Oblast Development Plan: Sughd Oblast Social Economic Plan OECD/DAC Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Development Co-operation Directorate PEI UNDP-UNEP Poverty-Environment Initiative PPD Public-Private -

Environmental Degradation, Migration, Internal Displacement, and Rural Vulnerabilities in Tajikistan

Environmental Degradation, Migration, Internal Displacement, and Rural Vulnerabilities in Tajikistan May 2012 This study was conducted with financial support from the International Organization for Migration Development Fund. In its activities, IOM believes that a humane and orderly migration responds to the interests of migrants and society, as a whole. As a leading intergovernmental organization IOM is working with its partners in the international community, guided by the following objectives: to promote the solution of urgent migration problems, improve understanding of the problems in the area of migration; encourage social and economic development through migration; assert the dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher: International Organization for Migration (IOM) Mission in the Republic of Tajikistan Dushanbe, 734013 22-A Vtoroy Proezd, Azizbekov Street Telephone: +992 (37) 221-03-02 Fax: +992 (37) 251-00-62 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.iom.tj © 2012 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any way - through electronic and mechanical means, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in this report represent those of individual authors and unless clearly labeled as such do not rep- resent the opinions of the International Organization for Migration. Environmental Degradation, Migration, Internal Displacement, and Rural Vulnerabilities in Tajikistan May 2012 Saodat Olimova Muzaffar Olimov ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors of this report express their deepest gratitude to Zeynal Hajiyev, Chief of IOM Mission in Tajikistan and the employees of the IOM country office, especially Moyonsho Mahmadbekov, Patrik Shirak and Zohir Navjavonov for their invaluable advice on improving the structure and content of this report. -

World Bank Document

SFG3307 Tajikistan Agency for Land Reclamation and Irrigation Public Disclosure Authorized ZARAFSHON IRRIGATION REHABILITATION AND MANAGEMENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized GENERIC ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized Dushanbe, April 22, 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Contents List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 12 National Environmental Assessment Regulatory Framework ...................................................... 15 World Bank Environmental Assessment Requirements ............................................................... 20 Baseline Environmental Analysis ................................................................................................. 22 Project Description........................................................................................................................ 25 Potential environmental and social impacts .................................................................................. 28 Generic Environmental Management Plan ................................................................................... 32 Environmental Monitoring and Reporting ................................................................................... -

Tajikistan Tajikistan

Tajikistan: Floods in Panjakent "On 8 June 2005, abundant rains in Panjakent district resulted in torrential floods. The population of six IFRC Information Bulletin No.1 villages was heavily affected." Issued 13 June 2005 GLIDE: FL-2005-000090-TJK SITUATION KAZAKHSTAN As a result of the floods, 345 people left without shelter, Affected population: 2,877 73 houses totally destroyed and 338 houses in four Affected villages: Shing, Dahani Ob, Bodgoh, Vagashton, Gijdavra villages are partly damaged. Other figures to date and Panjrood indicate 8 causalities and a total affected population of People without shelter: 345 KYRGYZSTAN 2,877. Destroyed house: 73 Damaged house: 338 Causualities: 8 ACTION oh The Red Crescent Society of Tajikistan, jointly with the h Asht UZBEKISTAN tc s a Ministry of Emergency Situations and Rapid Emergency M Ghafurov Konibodom Assessement and Coordination Team (REACT) Zafarobod Nov Djabbor Rasulov Isfara members, coordinated the activities to provide effective Istaravshan assistance to the suffered people. Shahriston Panjakent Ghonchi Kuhistoni Mastchoh Map projection: Geographic. Ayni Map data source: UN Cartographic Section, ESRI, UN. Gharm Jirgatol Tojikobod CHINA Code: IFRC Bulletin No. 01/2005 Kofarnihon v Varzob a a Darband d n i Tavildara o r Duchanbe Roghun z h n a u Hissor Darvoz h s Fayzobod von TAJIKISTAN r S g TAJIKISTAN u alju n T Norak B Vandj k li D t e v o S Khovali in a ovon a im Muminobod z Y n Murghob g Affected Villages Len o h Khojamaston h Rushon G a S Sarband r Kulob h a ur z Bokhtar Vose o -

Tajikistan Rural Water Supply Activity

TAJIKISTAN RURAL WATER SUPPLY ACTIVITY SITE SELECTION PLAN December 31, 2020 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. TAJIKISTAN RURAL WATER SUPPLY ACTIVITY SITE SELECTION PLAN Contract No. 72011520C00004 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 Authorization ....................................................................................................................... 1 Program Objectives ............................................................................................................ 1 Purpose of this Report ....................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................... 2 District Selection Process .................................................................................................. 2 Site Selection Process ......................................................................................................... 3 I. Background ................................................................................................ 4 II. District Selection ..................................................................................... -

WTO Documents Online

WORLD TRADE RESTRICTED WT/ACC/TJK/3 21 February 2003 ORGANIZATION (03-1106) Working Party on the Original: English Accession of the Republic of Tajikistan ACCESSION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN Memorandum on the Foreign Trade Regime In a communication circulated in document WT/ACC/TJK/1 on 29 May 2001, the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Tajikistan applied for accession under Article XII of the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO). The General Council established a Working Party (WT/ACC/TJK/2) on 26 July 2001 with the following terms of reference: "To examine the application of the Government of Tajikistan to accede to the WTO Agreement under Article XII, and to submit to the General Council recommendations which may include a draft Protocol of Accession." In accordance with the established procedures (WT/ACC/1), the Secretariat is circulating the attached Memorandum on the Foreign Trade Regime received from the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Tajikistan. WTO Members wishing to submit questions on the Memorandum are invited to do so by 24 March 2003 for transmission to the Republic of Tajikistan's authorities. _______________ WT/ACC/TJK/3 Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................1 II. ECONOMY, ECONOMIC POLICIES AND FOREIGN TRADE ......................................1 1. Economy ....................................................................................................................................1 -

Agricultural Expertise and Knowledge Practices Among Individualized Farm Households in Tajikistan

Agricultural Expertise and Knowledge Practices among Individualized Farm Households in Tajikistan Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Andreas Mandler aus Erfurt Bonn 2019 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Christoph Antweiler (Vorsitzender) Prof. Eva Youkhana (Gutachterin) Prof. Conrad Schetter (Gutachter) Prof. Anna-Katharina Hornidge (weiteres prüfungs- berechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 11. September 2018 2 Саҳар мегуфт булбул боғбонро, «Дар ин боғ ҷуз ниҳоли ғам нарӯяд, Ба пирӣ мерасад хори биёбон, Вале гул чун ҷавон гардад, бимирад». In the morning a nightingale told the gardener, “In this soil besides the seedling of sorrow nothing will grow. A desert thistle will reach old age But a flower, like a young person, may die.” Muhammad Iqbal 3 4 Table of Content ABSTRACT 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 13 NOTES ON LANGUAGE AND TRANSLITERATION 15 DEUTSCHE KURZFASSUNG 17 MAPS OF THE REGION 32 ACRONYMS AND GLOSSARY 34 1 INTRODUCTION: AGRICULTURAL KNOWLEDGE IN RURAL TAJIKISTAN 37 Post-Soviet Restructuration of the Tajik Agriculture 39 Agricultural Expertise and Political Economy in Rural Tajikistan 48 Knowledge and Expertise in the Individualized Agriculture? 51 Methodology: Knowledge Practices in Agriculture 52 Structure of the Thesis: Outlook on Chapters 56 2 KNOWLEDGE AND GOVERNANCE IN RURAL CENTRAL -

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Catholics Hold a Vigil for Activist Nguyen Van Dai, Who Was Badly Beaten by Unknown Attackers and Was Arrested for Anti-State “Propaganda.”

UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Catholics hold a vigil for activist Nguyen Van Dai, who was badly beaten by unknown attackers and was arrested for anti-state “propaganda.” Hanoi, Vietnam. Reuters/Kham Migrants protest outside a train that they are refusing to leave for fear of being taken to a refugee camp. Budapest, Hungary. Matt Cardy/Getty Images People attend a mass funeral A woman poses for a Girls rescued from Boko for Rajib Haider, an architect photograph at a memorial to Haram at Sambisa Forest line and blogger who was killed by An ethnic Uighur man passes pay tribute to the victims of up to collect donated clothes an extremist group. by security forces. the Paris attacks. at the Malkohi refugee camp. Dhaka, Bangladesh. Xinjiang, China. Yangon, Burma. Yola, Nigeria. Reuters/Andrew Biraj EPA Reuters/Olivia Harris Emmanuel Arewa/AFP/Getty A boat with Rohingya Muslim A Ahmadiyya Pakistani cries Police arrest a protesting People pay tribute to the migrants in waters near as she leaves a detention monk near the Chinese victims of the Hyper Cacher Koh Lipe Island. center with her family on Embassy visa section office. kosher supermarket attack. a bus. Thailand. Kathmandu, Nepal. Paris, France. Bangkok, Thailand. Christophe Archambault/ Reuters/Gopal Chitrakar Reuters/Yves Herman AFP/Getty Reuters/Damir Sagolj A girl waits to receive food provided by the United Nations’ World Food Programme (WFP) during a visit by a European Union A man stands near a car on Sunni Muslims who fled the delegation, at an IDP camp fire as Muslim families prepare A Crimean Tatar sits in the Islamic State’s strongholds of in Azaza. -

World Bank Document

Zarafshon Irrigation Rehabilitation and River Basin Management (ZIRP) Project Procurement Plan (P158576) Estimated Procurement Selection Bank Contract signing Public Disclosure Authorized Description Reference No amount in approach method oversight date (USD $) GOODS National, Vehicles ZIRP-RFQ-002 RFQ 90,000.00 Post Open National, Furniture for PMU and PCU ZIRP-RFQ-004 RFQ 20,000.00 Post Open CONSULTING SERVICES Detailed design, including Author supervision for Mastchohi kuhi, Ayni, Shahriston, ZIRP-СQS-007 National, Open СQS 140,000.00 Post Devashtich and Panjakent districts Public Disclosure Authorized Detailed design for Panjakent districts ZIRP-СQS-011 National, Open СQS 170,000.00 Post Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PROCUREMENT Tajikistan : Zarafshon Irrigation Rehabilitation and Management Improvement Project PLAN General Information Country: Tajikistan Bank’s Approval Date of the Original Procurement Plan: 2018-01-29 Revised Plan Date(s): (comma delineated, leave blank if none)2019-07-19 Project ID: P158576 GPN Date: 2018-01-30 Project Name: Zarafshon Irrigation Rehabilitation and Management Improvement Project Loan / Credit No: TF / A6507 Executing Agency(ies):Project Management Unit for the “Fergana Valley Water Resources Management Project” WORKS Bid Evaluation Activity Reference No. / Draft Bidding Loan / Credit Market Procurement Prequalification Actual Amount Process Draft Pre-qualification Prequalification Specific Procurement Bidding Documents Proposal Submission / Report and Description Component -

Power Sector Development Program: Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination August 2020 Tajikistan: Power Sector Development Program Prepared by Open Joint Stock Company Electricity Distribution Networks and Project Management Unit for Electro-Energy Sector, with support from Mercados-Aries International for the Asian Development Bank. This draft initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Draft Initial Environmental Examination Project number 53315-001 August 2020 Republic of Sector Operational Performance Tajikistan Improvements Project - Advanced Metering Infrastructure and Grid Enhancement in Dushanbe and selected cities Prepared by Open Joint Stock Company Electricity Distribution Networks and Project Management Unit for Electro-Energy Sector, with support from Mercados-Aries International for the Asian Development Bank. This draft initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff and may be preliminarв in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.