Technical University of Munich Master's Thesis Research Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE MAINTENANCE of MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING in ONLINE SECOND LANGUAGE TALK ADAM BRANDT Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository THE MAINTENANCE OF MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING IN ONLINE SECOND LANGUAGE TALK ADAM BRANDT Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Newcastle University School of Education, Communication and Language Sciences June 2011 Abstract Encounters in which at least one person is communicating in a second language (L2) are increasingly prevalent, and span many contexts and settings. However many of these settings remain under-researched, particularly those outside of formal language education (Firth & Wagner 1997, 2007; Wagner 2004). One such under-explored setting is the internet. In one particular internet context, L2 users of English have taken the opportunity to create voice-based chat rooms in which participants can practice their use of English. In such chat rooms, despite the huge variety in backgrounds and proficiencies, participants prove themselves to be highly skilled, resourceful and competent interactants, able to ensure mutual understanding as consistently and regularly as would be expected from first language users. However, as with any context involving any kind of interactants, there are occasions on which this mutual understanding appears to come under threat. This study applies conversation analysis (CA) to the examination of audio recordings of these online, voice-based chat rooms. More specifically, it provides a fine detailed examination of the work which is put in by the participants in order to pre-empt, and/or overcome, possible threats to mutual understanding (or ‘intersubjectivity’). Analysis show how participants are at times sensitive to such threats when dealing with (1) unspecified trouble in talk and (2) an absence of response to talk. -

Skype® for Dummies‰

01_048917 ffirs.qxp 12/8/06 8:26 PM Page iii Skype® FOR DUMmIES‰ by Loren and Susan Abdulezer and Howard Dammond Foreword by Niklas Zennström CEO and co-founder of Skype 01_048917 ffirs.qxp 12/8/06 8:26 PM Page ii 01_048917 ffirs.qxp 12/8/06 8:26 PM Page i Skype® FOR DUMmIES‰ 01_048917 ffirs.qxp 12/8/06 8:26 PM Page ii 01_048917 ffirs.qxp 12/8/06 8:26 PM Page iii Skype® FOR DUMmIES‰ by Loren and Susan Abdulezer and Howard Dammond Foreword by Niklas Zennström CEO and co-founder of Skype 01_048917 ffirs.qxp 12/8/06 8:26 PM Page iv Skype® For Dummies® Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River Street Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2007 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permit- ted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4355, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

What Are the Uses of Skype? What Does It Do? Who Uses Skype?

Skype Unknown macro: {align} Unknown macro: {logo} http://wiki.itap.purdue.edu/download/attachments/4293019/rsz_logo_-_skype-1.jpg "> Unknown macro: {align} Unknown macro: {logo} http://wiki.itap.purdue.edu/download/attachments/4293019/rsz_logo_-_skype-1.jpg What Are the Uses of Skype? What Does It Do? The main purpose of Skype is to connect people. People from around the world can connect through many different ways. They can connect through one or two way audio, one or two way video, one or two way audio and video or through text. People can also call any telephone around the world though this costs money, but talking between Skype users does not cost a thing. It can be used on Windows, Mac, and Linux operating systems so almost all computers are compatible. It also works with many different cell phones and mobile devices so individuals can use it whenever/wherever they want. It also can be used by a teacher who is teaching an online class. Unknown macro: {center} Who Uses Skype? Skype in Business Skype is used for businesses that need to reach people around the country or world for as cheap as possible. When business workers use Skype they can get more done, talk more to your clients, and cut your phone bill. Business workers can make free calls to people when they are using Skype and if they choose to call mobile phones or landlines it is very cheap.They can also use Skype from many mobile phones so you can use it anywhere. Skype also allows users to make video calls so business workers can make conference calls for free anytime, anywhere. -

Exploring CALL Options for Teaching EFL in Vietnam Nhon Thanh Dang Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2011 Exploring CALL Options for Teaching EFL in Vietnam Nhon Thanh Dang Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended Citation Dang, Nhon Thanh, "Exploring CALL Options for Teaching EFL in Vietnam" (2011). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 273. This APP is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Exploring CALL Options for Teaching EFL in Vietnam By Nhon Thanh Dang An Alternate Plan Paper Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May 2011 Date: March 29 th , 2011 This Alternate Paper Plan has been examined and approved. Examining Committee: _____________________________________________ Dr. ESTHER SMIDT, Committee Chair, Department of English ______________________________________________ Prof. & Dr. STEPHEN STOYNOFF, Committee -

Supplemental Guide For: UC-P100-S and UC-P110-S-PLUS

UC-P100-S & UC-P110-S-PLUS Crestron Flex VoIP Desk Phones for Skype® for Business Supplemental Guide Crestron Electronics, Inc. Crestron product development software is licensed to Crestron dealers and Crestron Service Providers (CSPs) under a limited non-exclusive, non-transferable Software Development Tools License Agreement. Crestron product operating system software is licensed to Crestron dealers, CSPs, and end-users under a separate End-User License Agreement. Both of these Agreements can be found on the Crestron website at www.crestron.com/legal/software_license_agreement. The product warranty can be found at www.crestron.com/legal/sales-terms-conditions-warranties. The specific patents that cover Crestron products are listed at www.crestron.com/legal/patents. Certain Crestron products contain open source software. For specific information, visit www.crestron.com/legal/open- source-software. Crestron and the Crestron logo are either trademarks or registered trademarks of Crestron Electronics, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Active Directory, Microsoft Teams, and Skype for Business are either trademarks or registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. Other trademarks, registered trademarks, and trade names may be used in this document to refer to either the entities claiming the marks and names or their products. Crestron disclaims any proprietary interest in the marks and names of others. Crestron is not responsible for errors in typography or photography.This document -

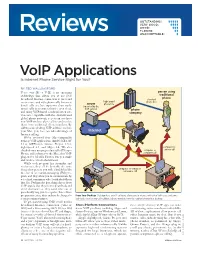

Voip Applications Is Internet Phone Service Right for You?

OUTSTANDING: mmmmm VERY GOOD: mmmm GOOD: mmm Reviews FLAWED: mm UNACCEPTABLE: m VoIP Applications Is Internet Phone Service Right for You? BY TED WALLINGFORD Voice over IP, or VoIP, is an emerging person using technology that allows you to use your traditional broadband Internet connection to place and standard phone receive voice and videophone calls. Internet- high-speed phone line server phone line based calls are less expensive than tradi- (operated by the tional calls (sometimes they’re even free), VoIP service) phone and many VoIP-based communication ser- company vices are compatible with the old-fashioned global phone network, so you can use these new VoIP tools to place calls to and receive them from traditional phone numbers. By adding some desktop VoIP software tools to your Mac, you, too, can take advantage of Internet Internet calling. We’ve reviewed four Mac-compatible desktop VoIP applications: Apple’s iChat AV 3.1.4, SIPPhone’s Gizmo Project 1.3.2, SightSpeed 4.5, and Skype 1.4. We also computer-to- checked out a unique product called Wengo- computer-to- phone call Phone; still in beta for the Mac, this VoIP computer call plug-in for Mozilla Firefox lets you make and receive calls via the browser. While each program has strengths and weaknesses, they all do basically the same computer-to-computer thing: they present you with a buddy list like conference call the one in an instant-messaging (IM) pro- gram, and they allow you to communicate by voice (and sometimes video) with the folks in that list. -

Skype for Business @ SUNY Cortland

Skype for Business @ SUNY Cortland About: Skype for Business is a powerful way to communicate with colleagues and students. It makes online communication more collaborative and engaging and you can use Skype for Business from nearly any computer or mobile device. Features of Skype for Business include: • Instant messaging • Audio-only calls on your computer or mobile device • Video calls on your computer or mobile device • Presence • Online meetings Skype for Business is not the same as Skype although the two do work together. Skype for Business is part of Microsoft Office 365 which is provided and managed by SUNY Cortland, whereas Skype is a consumer product available to anyone on the internet, and is not supported by the college. Also, regular Skype is for 1 to 1 calls (person to person), but Skype for Business is for 1 to 1 calls as well as 1 to many (conference calls, webinars), and it is a more robust and feature rich application. For full Skype for Business functionality, you must download and install the appropriate Skype for Business client for your computer or mobile device, and in order to use all of the Skype for Business features you will need a computer with a webcam and microphone or headset. The Memorial Library has laptops and webcams that can be "checked out" if you do not have a computer with these resources. IMPORTANT: All student, faculty and staff at SUNY Cortland are licensed for Skype for Business. In addition, although you must have an account to create meetings, anyone can join a Skype for Business meeting using only a Web browser. -

I 1. Voice.Tone.Dial 啊

1. voice.tone.dial 啊 i Microsoft Skype for Business Edition IP Phones Administrator Guide Copyright Copyright © 2019 YEALINK(XIAMEN) NETWORK TECHNOLOGY Copyright © 2019 Yealink (Xiamen) Network Technology CO., LTD. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, for any purpose, without the express written permission of Yealink (Xiamen) Network Technology CO., LTD. Under the law, reproducing includes translating into another language or format. When this publication is made available on media, Yealink (Xiamen) Network Technology CO., LTD. gives its consent to downloading and printing copies of the content provided in this file only for private use but not for redistribution. No parts of this publication may be subject to alteration, modification or commercial use. Yealink (Xiamen) Network Technology CO., LTD. will not be liable for any damages arising from use of an illegally modified or altered publication. Trademarks Yealink®, the logo and the name and marks is trademark of Yealink (Xiamen) Network Technology CO., LTD, which are registered legally in China, the United States, EU (European Union) and other countries. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. Without Yealink’s express written permission, recipient shall not reproduce or transmit any portion hereof in any form or by any means, with any purpose other than personal use. Warranty (1) Warranty THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS GUIDE ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS GUIDE ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE AND PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. -

Study on Differences Between Microsoft Skype for Business and Microsoft Skype Broadcast 1Siddarth Kaul, 2Dr Anuj Jain 1,2Bhagwant University Rajasthan India

IJCST VOL . 9, Iss UE 2, APR I L - JUNE 2018 ISSN : 0976-8491 (Online) | ISSN : 2229-4333 (Print) Study on Differences between Microsoft Skype for Business and Microsoft Skype Broadcast 1Siddarth Kaul, 2Dr Anuj Jain 1,2Bhagwant University Rajasthan India Abstract Broadcast Online is the Meetings can be setup anywhere across The paper proposes to clearly elaborate the differences and the Globe with simple and relatively easy licensing available by understanding of Microsoft Skype for business and Microsoft Microsoft under Different Plan categories with Live Broadcast Skype Broadcast as known Skype for Business is a Unified participants Ratio up to 10,000 participants. communication Platform (Formerly Known as Lync) for audio & Video Conferencing, IM and Image and File Transfer capabilities IV. Difference between Skype for Business and Skype which is a successful platform in the Market whereas Skype Meeting Broadcast Broadcast is a portal for Online schedule of Meeting Broadcast Skype for Business only provides the ability up to 250 participants and audio & Video Conferencing on Microsoft Portal. to collaborate Online by using Different features such as IM,Content sharing, Video, audio the meetings can be easily setup by the Keywords Outlook Office 365 Skype Client or by OWA. Skype, Unified Communication, Video Conferencing Skype Meeting Broadcast is a feature for Skype for Business Online and Office 365 which helps to schedule, produce and I. Introduction Broadcast LIVE meetings for up to 10,000 Participants. The Unified Communication has the potential to dramatically meetings can be scheduled from the skype online broadcast portal change and improve the Enterprise Communication or Business before scheduling any meeting the Licensing must be enabled for Communication in real world by reducing the overall enterprise the organization. -

SMART Room System with Skype for Business User's Guide

Help us make this document better smarttech.com/docfeedback/170818 USER’S GUIDE FOR MODELS SRS-LYNC-XS, SRS-LYNC-S-G5, SRS-LYNC-M, SRS-LYNC-M-DUAL, SRS-LYNC-L-G5 AND SRS-LYNC-XL FEATURING SMART BOARD® 8055i-G5, 8065i-G5 AND 8084i-G4 INTERACTIVE FLAT PANELS NOTE This documentation has been updated to support Microsoft’s transition from Lync® to Skype® for Business software. Most references to Lync have been removed and replaced with Skype for Business, however the following information is still applicable to SMART room systems running Lync software. Product registration If you register your SMART product, we’ll notify you of new features and software upgrades. Register online at smarttech.com/registration. FCC warning This equipment has been tested and found to comply with the limits for a Class A digital device, pursuant to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are designed to provide reasonable protection against harmful interference when the equipment is operated in a commercial environment. This equipment generates, uses and can radiate radio frequency energy and, if not installed and used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. Operation of this equipment in a residential area is likely to cause harmful interference in which case the user will be required to correct the interference at his own expense. この装置は、クラスA情報技術装置です。この装置を家庭環境で使用すると電波妨害を引き起こすことがあります。この場合には使用者が適切な対策を講ずるよ う要求されることがあります。 VCCI-A Trademark notice SMART Room System, SMART Board, SMART Meeting Pro, SMART Ink, DViT, smarttech, the SMART logo and all SMART taglines are trademarks or registered trademarks of SMART Technologies ULC in the U.S. -

Skype - Reasons for Growth

Stockholm School of Economics Marketing Department Skype - Reasons for Growth Master Thesis, 10 credits Author: Nils Hammar Tutor: Christopher Rosenqvist Spring 2007 CONTENT ABSTRACT ..........................................................................................................................................................2 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................................3 1.1 BACKGROUND..............................................................................................................................................3 1.2 OBJECTIVE ...................................................................................................................................................4 1.3 DELIMITATIONS ...........................................................................................................................................4 1.3.1 Users - Not Profit................................................................................................................................4 1.3.2 Why Net2Phone...................................................................................................................................5 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THESIS ................................................................................................................................6 3. METHODOLOGY ..........................................................................................................................................8 -

Siskye1 Usermanual

User Manual (English Version) Yeastar Technology Co., Ltd. SiSkyE1 User Manual Table of Contents 0 1.Introduction.......................................................................................... 4 2.Before You Proceed ................................................................................ 6 3.Installation Procedure............................................................................. 7 4.Installing YE110 Digital Card ................................................................... 8 5.Installing SiSkyE1 Software....................................................................10 6.Running SiSkyE1 Config.Wizard ..............................................................15 6.1 Launch the Config Wizard .................................................................16 6.2 Install YE110 Card Driver .................................................................16 6.3 Configure Skype for Each Port...........................................................17 6.4 Install Skype Cables ........................................................................19 6.5 Finish Config. Wizard .......................................................................20 7.Running SiSkyE1 Software .....................................................................21 8.Using SiSkyE1 ......................................................................................24 8.1 Dial Rule ........................................................................................24 8.2 Application of Branch Offices Connection.............................................29