From the Turing Test to a Wired Carnivalesque: on the Durability Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

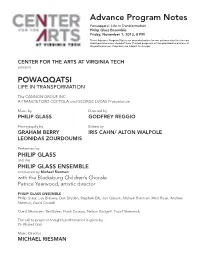

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

©2011 Campus Circle • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 Wilshire Blvd

©2011 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON TIME “It’s a heightened, almost hallucinatory sensual experience, and ESSENTIAL VIEWING FOR SERIOUS MOVIEGOERS.” RICHARD CORLISS THE NEW YORK TIMES “A COSMIC HEAD MOVIE OF THE MOST AMBITIOUS ORDER.” MANOHLA DARGIS HOLLYWOOD WEST LOS ANGELES EXCLUSIVE ENGAGEMENTS START FRIDAY, MAY 27 at Sunset & Vine (323) 464-4226 at W. Pico & Westwood (310) 281-8233 FOX SEARCHLIGHT FP. (10") X 13" CAMPUS CIRCLE - 4 COLOR WEDNESDAY: 5/25 ALL.TOL-A1.0525.CAM CC CC JL JL 4 COLOR Follow CAMPUS CIRCLE on Twitter @CampusCircle campus circle INSIDE campus CIRCLE May 25 - 31, 2011 Vol. 21 Issue 21 Editor-in-Chief 6 Yuri Shimoda [email protected] Film Editor 4 14 [email protected] Music Editor 04 FILM MOVIE REVIEWS [email protected] 04 FILM PROJECTIONS Web Editor Eva Recinos 05 FILM DVD DISH Calendar Editor Frederick Mintchell 06 FILM SUMMER MOVIE GUIDE [email protected] 14 MUSIC LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE Editorial Interns Intimate and adventurous music festival Dana Jeong, Cindy KyungAh Lee takes place over Memorial Day weekend. 15 MUSIC STAR WARS: IN CONCERT Contributing Writers Tamea Agle, Zach Bourque, Kristina Bravo, Mary Experience the legendary score Broadbent, Jonathan Bue, Erica Carter, Richard underneath the stars at Hollywood Bowl. Castañeda, Amanda D’Egidio, Jewel Delegall, Natasha Desianto, Stephanie Forshee, Jacob Gaitan, Denise Guerra, Ximena Herschberg, 15 MUSIC REPORT Josh -

Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever PDF Book

TRANSCEND: NINE STEPS TO LIVING WELL FOREVER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ray Kurzweil,Terry Grossman | 480 pages | 21 Dec 2010 | RODALE PRESS | 9781605292076 | English | Emmaus, PA, United States Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever PDF Book Archived from the original on 17 October Like some other Kurzweil books, he really catches your attention with some insane predictions. Error rating book. These are brain extenders that we have created to expand our own mental reach. He was involved with computers by the age of 12 in , when only a dozen computers existed in all of New York City, and built computing devices and statistical programs for the predecessor of Head Start. He obtained a B. Each chapter has its purpose and a plan for us readers to start applying the information. Ray's ideas are definitely futuristic. Inventing is a lot like surfing: you have to anticipate and catch the wave at just the right moment. The only thing I didn't like was their suggestion to eat so many dietary supplements such as vitamins and not including more defined suggestions on how to combine them. Aug 04, DJ rated it liked it. Products include the Kurzweil text-to-speech converter software program, which enables a computer to read electronic and scanned text aloud to blind or visually impaired users, and the Kurzweil program, which is a multifaceted electronic learning system that helps with reading, writing, and study skills. This is a 'how to Top charts. In , Visioneer, Inc. Development of these technologies was completed at other institutions such as Bell Labs, and on January 13, , the finished product was unveiled during a news conference headed by him and the leaders of the National Federation of the Blind. -

ROBERT WILSON / PHILIP GLASS LANDMARK EINSTEIN on the BEACH BEGINS YEARLONG INTERNATIONAL TOUR First Fully Staged Production in 20 Years of the Rarely Performed Work

For Immediate Release March 13, 2012 ROBERT WILSON / PHILIP GLASS LANDMARK EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH BEGINS YEARLONG INTERNATIONAL TOUR First Fully Staged Production in 20 Years of the Rarely Performed Work Einstein on the Beach 2012-13 trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OZ5hTfDzU9A&feature=player_embedded#! The Robert Wilson/Philip Glass collaboration Einstein on the Beach, An Opera in Four Acts is widely recognized as one of the greatest artistic achievements of the 20th century. Although every performance of the work has attracted a sold-out audience, and the music has been recorded and released, few people have actually experienced Einstein live. An entirely new generation—and numerous cities where the work has never been presented—will have the opportunity during the 2012-2013 international tour. The revival, helmed by Wilson and Glass along with choreographer Lucinda Childs, marks the first full production in 20 years. Aside from New York, Einstein on the Beach has never been seen in any of the cities currently on the tour, which comprises nine stops on four continents. • Opéra et Orchestre National de Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon presents the world premiere at the Opera Berlioz Le Corum March 16—18, 2012. • Fondazione I TEATRI di Reggio Emilia in collaboration with Change Performing Arts will present performances on March 24 & 25 at Teatro Valli. • From May 4—13, 2012, the Barbican will present the first-ever UK performances of the work in conjunction with the Cultural Olympiad and London 2012 Festival. • The North American premiere, June 8—10, 2012 at the Sony Centre for the Performing Arts, as part of the Luminato, Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity, represents the first presentation in Canada. -

2045: the Year Man Becomes Immortal

2045: The Year Man Becomes Immortal From TIME magazine. By Lev Grossman Thursday, Feb. 10, 2011 On Feb. 15, 1965, a diffident but self-possessed high school student named Raymond Kurzweil appeared as a guest on a game show called I've Got a Secret. He was introduced by the host, Steve Allen, then he played a short musical composition on a piano. The idea was that Kurzweil was hiding an unusual fact and the panelists — they included a comedian and a former Miss America — had to guess what it was. On the show , the beauty queen did a good job of grilling Kurzweil, but the comedian got the win: the music was composed by a computer. Kurzweil got $200. Kurzweil then demonstrated the computer, which he built himself — a desk-size affair with loudly clacking relays, hooked up to a typewriter. The panelists were pretty blasé about it; they were more impressed by Kurzweil's age than by anything he'd actually done. They were ready to move on to Mrs. Chester Loney of Rough and Ready, Calif., whose secret was that she'd been President Lyndon Johnson's first-grade teacher. But Kurzweil would spend much of the rest of his career working out what his demonstration meant. Creating a work of art is one of those activities we reserve for humans and humans only. It's an act of self-expression; you're not supposed to be able to do it if you don't have a self. To see creativity, the exclusive domain of humans, usurped by a computer built by a 17-year-old is to watch a line blur that cannot be unblurred, the line between organic intelligence and artificial intelligence. -

Approaching the 'Ought' Question When Facing the Singularity

Running Head: Approaching the “Ought” Question Approaching the “Ought” Question when Facing the Singularity1 Chad E. Brack National Defense University College of International Security Affairs April 1, 2015 DISCLAIMER: THE OPINIONS AND CONCLUSIONS EXPRESSED HEREIN ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL STUDENT AUTHOR AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY, THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE OR ANY OTHER GOVERNMENTAL ENTITY. REFERENCES TO THIS STUDY SHOULD INCLUDE THE FOREGOING STATEMENT. 1. This paper was a submission for CISA Master of Arts in Strategic Security Studies course 6933: Science, Technology, and War. The topic question was “can knowledge (output of science) be a bad thing for humans? How should humans view the Bill Joy–Ray Kurzweil debate? Approaching the “Ought” Question Many scholars agree that science itself should not be expected to answer “ought” questions (Bauer 1994; Feyerabend 1975; Midgley 1994; Hoover 2010). As a theoretically amoral system,2 science is simply the pursuit of knowledge or, as Kenneth Hoover (2010) puts it, “a strategy for learning about life and the universe” (134). Science easily provides us with three of the four types of knowledge: empirical, analytical, and theoretical. Normative knowledge, however, stems from human values and norms. It is not scientific by nature and can be highly relative and subjective. Normative questions require “other forms of understanding” (Hoover 2010, 130), which come from many faucets of human experience (including the three types of knowledge listed above). The empirical, analytical, and theoretical knowledge that science provides us is neither good nor bad. It simply is. It is the application of that knowledge — in the form of technology — in which the “ought” question comes into play. -

Einstein on the Beach an Opera in Four Acts ROBERT WILSON & PHILIP GLASS

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Friday, October 26, 2012, 6pm Saturday, October 27, 2012, 5pm Sunday, October 28, 2012, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Einstein on the Beach An Opera in Four Acts ROBERT WILSON & PHILIP GLASS Choreography by Lucinda Childs with Helga Davis Kate Moran Jennifer Koh Spoken Text Jansch Lucie Christopher Knowles/Samuel M. Johnson/Lucinda Childs with The 2012 production of Einstein on the Beach, An Opera in Four Acts was commissioned by: The Lucinda Childs Dance Company Cal Performances; BAM; the Barbican, London; Luminato, Toronto Festival of Arts and Creativity; De Nederlandse Opera/The Amsterdam Music Theatre; Opéra et Orchestre Music Performed by National de Montpellier Languedoc-Rousillon; and University Musical Society of the The Philip Glass Ensemble University of Michigan. Michael Riesman, Conductor World Premiere: March 16, 2012, Montpellier, France. Music/Lyrics Direction/Set and Light Design Originally produced in 1976 by the Byrd Hoffman Foundation. Philip Glass Robert Wilson Lighting Sound Costumes Hair/Makeup Urs Schönebaum Kurt Munkasci Carlos Soto Campbell Young Associates: Because Einstein on the Beach is performed without intermission, the audience is invited to leave Luc Verschueren and re-enter the auditorium quietly, as desired. Café Zellerbach will be open for your dining pleasure, serving supper until 8pm and smaller bites, spirits, and refreshments thereafter. The Café is located on the mezzanine level in the lobby. Associate Producer Associate Producer Senior Tour Manager Production Manager Kaleb Kilkenny Alisa E. Regas Pat Kirby Marc Warren Music Director Co-Director Directing Associate Michael Riesman Ann-Christin Rommen Charles Otte These performances are made possible, in part, by the National Endowment for the Arts, and by Patron Sponsors Louise Gund, Liz and Greg Lutz, Patrick McCabe, and Peter Washburn. -

The Gaze in Theory

THE GAZE IN THEORY: THE CASES OF SARTRE AND LACAN Melinda Jill Storr Thesis submitted for DPhil degree University of York Centre for Women's Studies April 1994 ABSTRACT The topic of my research is the 'hierarchy of the senses' as it appears in mainstream Western thought, and specifically the privilege accorded to vision in twentieth century literary and theoretical writings. My aim is to investigate the allegation (as made by, for example, Evelyn Fox Keller and Christine Grontowski, and by Luce Irigaray) that the metaphor of vision is intimately connected with the construction of gender and sexual difference, and that the traditional privilege of vision acts to perpetuate the privilege of masculinity in modern writing practices. This allegation, captured in the thesis that masculinity 'looks' and femininity is 'looked-at' - that, as John Berger puts it, 'ben act and women appear" - has some degree of currency in contemporary writings an 'sexual difference', but has in itself received little critical attention. Taking the philosopher and novelist Jean-Paul Sartre and the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan as 'case studies', I investigate the plausibility of this allegation by means of a detailed analysis of the use of vision and its relation to gender in the respective works of each. This work represents a significant contribution to serious critical work an both Sartre and Lacan, and to the understanding of the relationship between gender and representation. 2 CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 8 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION 9 CHAPTER -

IBC Bioethics & Film Special Topic: Workshop/Interactive Session

IBC Bioethics & Film Special Topic: Workshop/Interactive Session: Teaching with Bioethics Documentaries & Films Thursday, June 9, 2016; 5:30-6:30 pm Laura Bishop, Ph.D. I. Introductory Remarks II. Bioethics & Film: Why, Practical Details, and Resources A. Why? Using video / film in the classroom or committee setting (handout) B. Practical Details 1. Preparation Time (editing and laying the groundwork) 2. Post-Viewing Time/Debriefing (ensuring viewers took home the right message; correcting false information) 3. Real Issues / Cases (documentary, non-fiction, fiction/entertainment; real cases get you more mileage) 4. Sensitivity (visual presentation may be overwhelming for some) 5. Mix Serious / Humorous – short clip – Cutting Edge: Genetic Repairman Sequence 6. Variety of Types 7. Range of Lengths 8. Copyright / Permissions Issues / Educational Licensing (trailers used) C. Resources 1. List of some sources to identify, watch, purchase bioethics-related videos/films (handout) 2. List of commercial films with bioethics themes (online) III. Workshop Piece / Interactive (Tools for Using Films) (see multi-page activity handout) Ø Who Decides: Ethics for Dental Practitioners (individual analysis to group discussion) Ø Me Before You and The Intouchables (compare, contrast, similarities) Ø Beautiful Sin (argument analysis: arguments pro & con; rules vs. outcomes) Ø Perfect Strangers (pretest/posttest; know, learn, need to know; double entry journal; discussion Q.) (http://www.perfectstrangersmovie.com; www.jankrawitz.com) Ø Just Keep Breathing: Moral Distress in the PICU (Pediatric Intensive Care Unit) (standing in the shoes - role play; ethics committee) (http://www.justkeepbreathingfilm.com) Case One Case Two IV. IBC42 Group Idea Sharing V. Resources: Jeanne Ting Chowning, MS, and Paula Fraser, MLS. -

Transcendent Man” Debuts on Dvd May 24

EXPLORING THE LIFE OF RAY KURZWEIL, “TRANSCENDENT MAN” DEBUTS ON DVD MAY 24 Inspired by Kurzweil’s Best-Selling Book, “The Singularity Is Near,” New Documentary Explores the Life and Ideas of the Inventor, Futurist, and Author April 22, 2011, New York, NY -- In Ray Kurzweil’s post-biological world, boundaries blur between human and machine, real and virtual. World hunger and poverty are solved, human aging and illness are reversed and we vastly extend longevity. Barry Ptolemy’s compelling feature-length documentary, TRANSCENDENT MAN, chronicles the life of one of our most respected and provocative advocates of the role of technology in the future. Docurama Films’ new release will be available for the first time on DVD on May 24, following a worldwide festival tour and a Digital/VOD release in March 2011. In his film, director Barry Ptolemy follows Kurzweil to more than 20 cities and 5 countries as he presents the daring arguments from his bestselling book, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. Kurzweil predicts that with the ever-accelerating rate of technological change, humanity is fast approaching an era in which our intelligence will become increasingly non- biological and millions of times more powerful. Within 25 years, computers will have consciousness. Humans will merge with their machines. These predictions make Kurzweil a prophetic genius to some, and a “highly sophisticated crackpot” to others. There is no question, however, that he has predicted the future with more accuracy than anyone else in history. TRANSCENDENT MAN explores the social and philosophical implications of Kurzweil’s predictions and the potential threats they pose to human civilization through dialogue with Colin Powell; technologists Hugo de Garis, Peter Diamandis, Kevin Warick, and Dean Kamen; journalist Kevin Kelly; musician Stevie Wonder, and William Shatner. -

Philip Glass an Evening in Chamber Music Featuring Philip Glass & Tim Fain

BRAVE NEW ART PHILIP GLASS AN EVENING IN CHAMBER MUSIC FEATURING PHILIP GLASS & TIM FAIN JUNE 20 & 21, 2014 OZ SUPPORTS THE CREATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENTATION OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY PERFORMING AND VISUAL ART WORKS BY LEADING ARTISTS WHOSE CONTRIBUTION INFLUENCES THE ADVANCEMENT OF THEIR FIELD. ADVISORY BOARD Amy Atkinson Karen Elson Jill Robinson Anne Brown Karen Hayes Patterson Sims Libby Callaway Gavin Ivester Mike Smith Chase Cole Keith Meacham Ronnie Steine Jen Cole Ellen Meyer Joseph Sulkowski Stephanie Conner Dave Pittman Stacy Widelitz Gavin Duke Paul Polycarpou Betsy Wills Kristy Edmunds Anne Pope Mel Ziegler aA MESSAGE FROM OZ This is indeed a special night. We are thrilled to present a brilliant program of works composed and performed by the inimitable Philip Glass, and accompanied by violin virtuoso Tim Fain. Throughout a career spanning nearly fifty years, Glass’s unique style and open-minded approach to composing has helped re-define our notions of what opera, symphony, film scores and chamber music can be, while inspiring a great many in the process. A graduate of The Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia and The Juilliard School, Tim Fain is a one-of-a-kind violinist whose work you have heard, even if his name is not familiar. With soundtrack film performances in the Grammy Award winning features, 12 Years a Slave and Black Swan, Fain has proven – like Philip Glass – that an audience for his music can be found in the great concert halls of the world, as well as on the silver screen. We are absolutely delighted and truly honored to welcome Philip Glass and Tim Fain to perform at OZ as our inaugural artistic program comes to a close. -

Digital Integration Jacob C

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 6-29-2016 Digital Integration Jacob C. Boccio University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Boccio, Jacob C., "Digital Integration" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6183 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digital Integration by Jacob C. Boccio A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts with a concentration in Film Studies Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Benjamin Goldberg, Ph.D. Amy Rust, Ph.D. Paul Hillier, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 21, 2016 Keywords: science fiction, artificial intelligence, film, identity and alienation Copyright © 2016, Jacob C. Boccio Table of Contents Abstract ii Chapter 1 1 Chapter 2 12 Technology Extension 12 Elysium 12 Surrogates 15 Machine AI 22 Terminator 23 Come with Me if You Want to Live 24 Blade Runner 25 I’ll Be Back 29 Machine Becoming Human 31 Bicentennial Man 32 Downloading the Mind 33 Transcendence 34 Chapter 3 39 Sentient A.I. 39 Chappie 39 Ex Machina 43 Coda 56 Bibliography 59 i Abstract Artificial intelligence is an emerging technology; something far beyond smartphones, cloud integration, or surgical microchip implantation.