Telescopes, Theodolites and Failing Vision in William Wordsworth's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

North West Inshore and Offshore Marine Plan Areas

Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Marshall Paul Macrae 1.0 Paul Macrae Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Paul Macrae Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

A Tectonic History of Northwest England

A tectonic history of northwest England FRANK MOSELEY CONTENTS Introduction 56x Caledonian earth movements 562 (A) Skiddaw Slate structures . 562 (B) Borrowdale Volcanic structures . 570 (C) Deformation of the Coniston Limestone and Silurian rocks 574 (D) Comment on Ingleton-Austwick inlier 580 Variscan earth movements. 580 (A) General . 580 (B) Folds 584 (C) Fractures. 587 4 Post Triassic (Alpine) earth movements 589 5 References 59 ° SUMMARY Northwest England has been affected by the generally northerly and could be posthumous Caledonian, Variscan and Alpine orogenies upon a pre,Cambrian basement. The end- no one of which is entirely unrelated to the Silurian structures include early N--S and later others. Each successive phase is partially NE to ~NE folding. dependent on earlier ones, whilst structures The Variscan structures are in part deter- in older rocks became modified by succeeding mined by locations of the older massifs and in events. There is thus an evolutionary structural part they are likely to be posthumous upon sequence, probably originating in a pre- older structures with important N-S and N~. Cambrian basement and extending to the elements. Caledonian wrench faults were present. reactivated, largely with dip slip movement. The Caledonian episodes are subdivided into The more gentle Alpine structures also pre-Borrowdale Volcanic, pre-Caradoc and follow the older trends with a N-s axis of warp end-Silurian phases. The recent suggestions of or tilt and substantial block faulting. The latter a severe pre-Borrowdale volcanic orogeny are was a reactivation of older fault lines and rejected but there is a recognizable angular resulted in uplift of the old north Pennine unconformity at the base of the volcanic rocks. -

The English Lake District

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum 10-1980 The nE glish Lake District La Salle University Art Museum James A. Butler Paul F. Betz Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum; Butler, James A.; and Betz, Paul F., "The nE glish Lake District" (1980). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 90. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/90 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T/ie CEnglisti ^ake district ROMANTIC ART AND LITERATURE OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT La Salle College Art Gallery 21 October - 26 November 1380 Preface This exhibition presents the art and literature of the English Lake District, a place--once the counties of Westmorland and Cumber land, now merged into one county, Cumbria— on the west coast about two hundred fifty miles north of London. Special emphasis has been placed on providing a visual record of Derwentwater (where Coleridge lived) and of Grasmere (the home of Wordsworth). In addition, four display cases house exhibits on Wordsworth, on Lake District writers and painters, on early Lake District tourism, and on The Cornell Wordsworth Series. The exhibition has been planned and assembled by James A. -

![PLATES XLI-XLIII.] Contentse Page I](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8435/plates-xli-xliii-contentse-page-i-708435.webp)

PLATES XLI-XLIII.] Contentse Page I

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of Liverpool on June 23, 2016 402 MR. BXS~ARD sMI~ oN THg [Sept. i912 , 22. The GI, ACIATI0~ of the BLACK COMBE DISTRICT (CUMBERLAND). By BERNARD SMITH, ~[.A., F.G.S. (Read March 17th, 1912.) [PLATES XLI-XLIII.] CONTENTSe Page I. Introduction ...................................................... 402 II. Geological Structure ............................................ 405 III. Pre-Glacial Condition of the District ........................ 407 IV. The Maximum Glaciation ....................................... 407 V. (1) The Lake-District Ice ....................................... 408 (2) The Irish-Sea Ice .......................................... 412 VI. The Drift-Deposits of the Plain and the Adjacent Hill- Slopes ............................................................ 412 VII. The Lower Boulder Clay ....................................... 416 (1) The Coast-Sections ...................................... 416 (2) The Inland Sections .................................... 417 VIII. Distribution of Scottish Boulders ........................... 420 IX. Phenomena occurring during the Retreat of the Ice ... 421 (1) Moraines and Trails of Boulders ..................... 421 (2) Marginal Channels and Associated Sands and Gravels ................................................ 423 (3) Sand and Gravel of the Plain ........................ 438 (4) The Whicham-Valley and Duddon-Estuary Lakes. 44i X. The Upper Boulder Clay ....................................... 445 XI. Corrie-Glaciers -

RR 01 07 Lake District Report.Qxp

A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas Integrated Geoscience Surveys (North) Programme Research Report RR/01/07 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/01/07 A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the District and adjacent areas Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2004. D Millward Keywords Lake District, Lower Palaeozoic, Ordovician, Devonian, volcanic geology, intrusive rocks Front cover View over the Scafell Caldera. BGS Photo D4011. Bibliographical reference MILLWARD, D. 2004. A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/01/07 54pp. -

Next Championship Races

The ‘CFR 30th Anniversary ’- by Tom Chatterley (report below) Cumberland Fell Runners Newsletter- WINTER 2016-17 Welcome to the first newsletter of 2017. There is plenty to read and think about in this issue. Thank you to all contributors. You can find more about our club on our website www.c-f-r.org.uk , Facebook & Twitter. In this issue. Did you know ? –LOST on BLACKCOMBE .Photo Quiz –Jim Fairey Club Meeting news-Jenny Chatterley Winter League Winners –Jane Mottram Next Championship Races Book Club –Paul Johnson Club Kit- Ryan Crellin Juniors News Club Runs WANTED! –Volunteers CFR 30th Anniversary –Jane Mottram Wasdale Wombling- Lindsay Buck CFR at 30- Barry Johnson Race Reports Blake,-Crummock, Jarret’s Jaunt, Carrock, Long Mynd.. Feature Race - Eskdale Elevation – David Jones Other News. View from Latrigg –by Sandra Mason Did You Know!— LOST on BLACK COMBE !!! Several members went walkabout on the Black Combe fell race ! Not surprising as the mist was down to the bottom of the fell! Interesting screen shot from Strava of the flybys from our club... no naming and shaming here though! And... a faithful CFR dog also found himself lost and was rescued by another brave CFR dog! And ... someone lost/forgot their dibber! And... Two club members lost their car after navigating the course perfectly! And...someone lost the contents of their stomach on the way home! Claire and Jennie --‘You did what !!’ Some of the members home safe . Are the others still out there or hiding in shame? Club Meeting Summary Tuesday 14th March –by Jennie Chatterley, Club Secretary Charlotte Akam Matthew Aleixo Nick Moore- Chair Colin Burgess Tamsin Cass Kate Beaty- Treasurer Jenny Jennings Ryan Hutchinson Jennie Chatterley- Secretary Peter Mcavoy Andy Ross Paul Jennings- Membership and website Rosie Watson Andy Bradley- Statistician Official welcome to Hannah & Jen Bradley - Dot Patton- Newsletter completing the full Bradley family as CFR competing Jane Mottram- Press officer members. -

Grizedale Leaflet Innerawk)

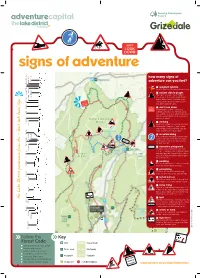

DON’T LOOK DOWN signs of adventure how many signs of Harter Fell adventure can you find? Mardale Ill Bell Mardale Thonthwaite Crag spaghetti junction Ignore the directions of the signs and keep on going. Red Screes Red not just elderly people Caudale Moor That’s right…we mean Coniston Old Man! Scandale Pass There is more to the Adventure Capital than fell walking. Want a change? Try mountain biking, Dove Crag DON’T climbing, horse riding or even a hot air balloon Hart Crag LOOK for a different view of the Lakes. DOWN sign ’ DON’T don’t look down Fairfield n LOOK And why would you? With countless walks, DOWN scrambles and climbs in the Adventure Capital the possibilities are endless. Admire the panorama, Helvellyn familiarise yourself with the fell names and choose which one to explore! climbing Helm Crag t look dow Known as the birthplace of modern rock climbing Steel Fell ’ following Walter Parry Haskett Smith’s daring n ascent of Napes Needle in 1884 the Adventure do Capital is home to some classic climbs. ‘ High Raise mountain biking Hours can be spent exploring the network of trails Pavey Ark Pavey and bridleways that cover the Adventure Capital. Holme Fell A perfect place to start is Grizedale’s very own The North Face Trail. Harrison Stickle adventure playground The natural features that make the Lake District Pike of Stickle Pike scenery so stunning also make it a brilliant natural adventure playground. Conquer the fells, scale the crags, hit the trails and paddle or swim the Lakes Pike of Blisco Pike that make it famous. -

February 2008: the Christmas Issue. New Year, New Races

NewsieBlack Combe Runners February 2008: the Christmas issue. New year, new races. New beer. It came as a shock when Will asked me for some words for the Newsie, as I was now Club Captain, but knowing I can’t wriggle out, here they are. Firstly, thanks to those at the AGM for your show of faith in me seeing that I’ve only been in the club a year, and thanks to Penny for her support as Captain. Both Hazel and I have been really pleased with the reception and friendliness of all in the club over the last year and it has made a huge difference to the enjoyment we’ve had running. We all run for fun, for some it is running and chatting on a Tuesday night, for others it is racing and drinking as much as is financially viable at the weekend. Our aim has to be to maintain this and help people to take part and stretch themselves when and where they want to. This photograph was taken by Dave Watson. That’s the only explanation I can offer. Ed. The winter league races, excellently organised by Val with her mallet, have attracted a lot of interest with 26 people We had 9 wanting to run last year so it’s a reasonable having competed in the first four races, most having hope. As a number of us found out in running it for the run two or more. The overall result is still wide open, first time in 2007, it’s a great team day out, with a little particularly as Val hasn’t told us how she will handicap us running thrown in and a few beers afterwards. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Note: Page numbers in italic type refer to illustrations; those in bold type refer to tables. Acadian Orogeny 147, 149 Cambrian-Silurian boundary. 45 occurrence of Skiddaw Slates 209 application to England 149 correspondence 43 thrusting 212 cause of 241 Green on 82 topography 78 cleavage 206,240 Hollows Farm 124 Black Combe sheet 130 deformation 207,210,225,237 Llandovery 46 black lead see graphite and granites 295 maps 40-41 Blackie, Robert 176 and lapetus closure 241,294 portrait 40 Blake Fell Mudstones 55 Westmorland Monocline 233,294 section Plate IV Blakefell Mudstone 115 accessory minerals 96 on unconformity below Coniston Limestone Series 83 Blea Crag 75 accretionary prism model 144, 148, 238 Bleaberry Fell 46 accretionary wedge, Southern Uplands 166, 237 Backside Beck 59.70. 174 Bleawath Formation 276,281 Acidispus 30 backthrusts 225,233,241. 295 Blencathra 162 Acritarchs Bad Step Tuff 218, 220 see also Saddleback Bitter Beck 118 Bailey, Edward B. 85, 196 Blengdale 276 Calder River 198 Bakewell, Robert 7,10 Blisco Formation 228 Caradoc 151 Bala Group 60, 82 Boardman, John 266, 269 Charles Downie on 137 Bala Limestone Bohemian rocks, section by Marr 60 Holehouse Gill 169, 211,221,223 Caradoc 21 Bolton Head Farm 276 Llanvirn 133 and Coniston Limestone 19.22, 23.30 Bolton. John 24, 263 Troutbeck 205 and lreleth Limestone 30 Bonney, Thomas 59 zones 119 Middle Cambrian 61 boreholes 55 Actonian 173, 179 Upper Cambrian 20 Nirex 273 Agassiz, Louis 255,257 Bala unconformity 82, 83.85 pumping tests 283, 286 Agnostus rnorei 29 Ballantrae complex 143 Wensleydale 154 Aik Beck 133 Balmae Beds 36 Borrowdale 9, 212,222 Airy, George 9 Baltica 146, 147, 240. -

A Guide Through the District of the Lakes in the North of England : With

Edward M. Rowe Collection of William Wordsworth DA 670 .LI W67 1835 L. Tom Perry Special Collections Harold B. Lee Library Brigham Young University BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY 3 1197 23079 8925 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/guidethroughdistOOword 1* "TV- I m #j GUIDE THROUGH THE * DISTRICT OF THE LAKES IN Ctie Nortf) of iSnglantr, WITH A DESCRIPTION OF THE SCENERY, &c. FOR THE USE OF TOURISTS AND RESIDENTS. FIFTH EDITION, WITH CONSIDERABLE ADDITIONS. By WILLIAM WORDSWORTH. KENDAL: PUBLISHED BY HUDSON AND NICHOLSON, AND IN LONDON BY LONGMAN & CO., r.'CXON, AND r." ! tTAE^lH & CO. Ytyll U-20QC& CjMtfo J YJoR , KENDAL: Printed by Hudson and Nicholson. ... • • • Tl^-i —— CONTENTS. DIRECTIONS AND INFORMATION FOR THE TOURIST. Windermere,—Ambleside.—Coniston.— Ulpha Kirk. Road from Ambleside to Keswick.—Grasmere,—The Vale of Keswick.—Buttermere and Crummock.— Loweswater. —Wastdale. —Ullswater, with its tribu- - i. tary Streams.—Haweswater, &c. Poge% DESCRIPTION of THE SCENERY of THE LAKES. SECTION FIRST. VIEW OF THE COUNTRY AS FORMED BY NATURE. Vales diverging from a common Centre.—Effect of Light and Shadow as dependant upon the Position of the Vales. — Mountains, — their Substance,—Surfaces, and Colours. — Winter Colouring. — The Vales, Lakes,— Islands, —Tarns, -— Woods,— Rivers,— Cli- mate,—Night. - - - p. 1 SECTION SECOND. I ASPECT OF THE COUNTRY AS AFFECTED BY ITS INHABITANTS. Retrospect. —Primitive Aspect.—Roman and British Antiquities, — Feudal Tenantry, — their Habitations and Enclosures.—Tenantry reduced in Number by the Union of the Two Crowns.— State of Society after that Event. —Cottages,—Bridges,—Places of Wor- ship, —Parks and Mansions.—General Picture of So- ciety.