PLATES XLI-XLIII.] Contentse Page I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North West Inshore and Offshore Marine Plan Areas

Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the North West Inshore and Offshore marine plan areas September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Marshall Paul Macrae 1.0 Paul Macrae Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris MMO Comments Graham, David Hutchinson 2.0 Paul Macrae Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Independent QA Sweeting © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report

_ Natural Environment Research Council Institute of Geological Sciences Mineral Reconnaissance Programme Report . -. - -_ A report prepared for the Department of Industry This report relates to work carried out by the Institute of Geological Sciences on behalf of the Department of Industry. The information contained herein must not be published without reference to the Director, institute of Geological Sciences D. Ostle Programme Manager Institute of Geological Sciences 154 Clerkenwell Road London EC1 R 5DU No. 21 A geochemical drainage survey of the Fleet granitic complex and its environs - - -; INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES Natural Environment Research Council Mineral Reconnaissance Programme 1 Report No. 21 A geochemical drainage survey of the Fleet granitic complex and its environs Metalliferous Minerals and Applied Geochemistry Unit R. C. Leake, BSc, PhD M. J. Brown, BSc Analytical and Ceramics Unit T. K. Smith BSc, BSc A. R. Date, BSc, PhD I 0 Crown copyright 7978 I London 1978 A report prepared for the Department of Industry Mineral Reconnaissance Proclramme Retorts The Institute of Geological Sciences was formed by the incorporation of the Geological Survey of Great Britain and 1 The concealed granite roof in south-west Cornwall the Geological Museum with Overseas Geological Surveys and is a constituent body of the Natural Environment 2 Geochemical and geophysical investigations around Research Council Garras Mine, near Truro, Cornwall 3 Molybdenite mineralisation in Precambrian rocks near Lairg, Scotland 4’ Investigation of -

A Landscape Fashioned by Geology

64751 SNH SW Cvr_5mm:cover 14/1/09 10:00 Page 1 Southwest Scotland: A landscape fashioned by geology From south Ayrshire and the Firth of Clyde across Dumfries and Galloway to the Solway Firth and northeastwards into Lanarkshire, a variety of attractive landscapes reflects the contrasts in the underlying rocks. The area’s peaceful, rural tranquillity belies its geological roots, which reveal a 500-million-year history of volcanic eruptions, continents in collision, and immense changes in climate. Vestiges of a long-vanished ocean SOUTHWEST are preserved at Ballantrae and the rolling hills of the Southern Uplands are constructed from the piled-up sediment scraped from an ancient sea floor. Younger rocks show that the Solway shoreline was once tropical, whilst huge sand dunes of an arid desert now underlie Dumfries. Today’s landscape has been created by aeons of uplift, weathering and erosion. Most recently, over the last 2 million years, the scenery of Southwest Scotland was moulded by massive ice sheets which finally melted away about 11,500 years ago. SCOTLAND SOUTHWEST A LANDSCAPE FASHIONED BY GEOLOGY I have a close personal interest in the geology of Southwest Scotland as it gave me my name. It comes of course from the town of Moffat, which is only a contraction of Moor Foot, which nestles near the head of a green valley, surrounded by hills and high moorland. But thank God something so prosaic finds itself in the midst of so SCOTLAND: much geological drama. What this excellent book highlights is that Southwest Scotland is the consequence of an epic collision. -

Fell and Mountain Marathon Gear

ANY PLACE - ANY TIME THE PLACE: KESKADALE (NEWLANDS) THE TIME: 1.30 pm SATURDAY, JULY THIS COMPETITOR'S BOOTS DISINTEGRATED (NOT WALSH'S) ON DESCENDING KNOTT RIGG ON THE FIRST DAY OF THE SAUNDERS TWO DAY MM WE WERE ON HAND TO SUPPLY HIM WITH A NEW PAIR OF WALSH'S, SO THAT HE COULD CONTINUE, IT PAYS TO HAVE FLEXIBLE FRIENDS! WINTER IS COMING. UNBEATABLE LIFA PRICES HELLY HANSEN LONG SLEEVE TOPS NAVY PIN STRIPE SML £6.95 GREY SML £6.95 NAVY SML £12.95 ROYAL SML £12.95 RED SML £12.95 LONG JOHNS NAVY (SECONDS) SML £5.95 ROYAL SML £12.95 LIFA BALACLAVA NAVY ONE SIZE £3.95 UFA BRIEFS NAVY SML £8.95 FASTRAX GLOVES SML £4.95 THE ONLY SPECIALIST RUNNING CENTRE IN BRITAIN THAT CATERS ESPECIALLY FOR THE FELL RUNNER. MAJOR STOCKISTS OF WALSH PB'S, WRITE OR RING FOR PRICE LIST. FAST EFFICIENT MAIL ORDER SERVICE. ACCESS OR VISA WELCOME. PETE BLAND SPORTS 34A KIRKLAND, KENDAL CUMBRIA. Telephone (0539) 731012 CONTENTS Page Editorial 1 EDITORIAL Letters 2 Magazine Turnround Gripping Yarns No 3 Wheeze 4 Various letters to me have raised questions about magazine Committee News turnround and topicality of results published. There are many FRA Officers and Committee Members 5 contributors to the magazine and several of them seem to assume that copy sent two weeks after the published deadline Membership Form 5 can just be slipped in. Photographers need to find time to get Committee News, Selwyn Wright 5 into their darkrooms on the deadline date. Then there have First Edale Navigation, Training and Safety Course, been problems with the printer reading discs and handwriting, Peter Knott 6 interpreting the required layout, and producing proofs and International News modified proofs. -

The Queen's Platinum Jubilee Beacons 8 2Nd June 2022

The Queen’s Platinum Jubilee Beacons 8 2nd June 2022 YOUR GUIDE TO TAKING PART Introduction A warm welcome to all our fellow celebrators. • A beacon brazier with a metal shield. This could be built by local craftsmen/women or adopted as a project by a school or There is a long and unbroken tradition in our country of college (see page 13). celebrating Royal Jubilees, Weddings and Coronations with the lighting of beacons - on top of mountains, church • A bonfire beacon and (see page 14) and cathedral towers, castle battlements, on town and village greens, country estates, parks and farms, along Communities with existing beacon braziers are encouraged to beaches and on cliff tops. In 1897, beacons were lit to light these on the night. celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. In 1977, 2002 and 2012, beacons commemorated the Silver, If you wish to take part, you can register your participation by Golden and Diamond Jubilees of The Queen, and in 2016 providing the information requested on page 10 under the Her Majesty’s 90th birthday. heading, "How to take part," sending it direct to [email protected]. Town Crier, James Donald - Howick, New Zealand. On 2nd June 2022, we will celebrate another unique milestone in our history, Her Majesty The Queen’s 70th year as our Monarch and Head of the Commonwealth - her Platinum Jubilee. It is a feat no previous monarch has achieved. More than 1,500 beacons will be lit throughout the United Kingdom, Channel Islands, Isle of Man and UK Overseas Territories, and one in each of the capital cities of Commonwealth countries in recognition of The Queen’s long and selfless service. -

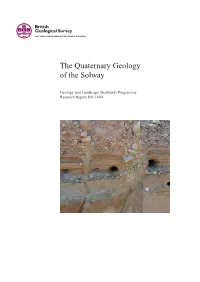

The Quaternary Geology of the Solway

The Quaternary Geology of the Solway Geology and Landscape (Scotland) Programme Research Report RR/11/04 HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are book- marked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub- headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the GEOLOGY AND LANDSCAPE (SCOTLAND) PROGRAMME Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. RESEARCH REPORT RR/11/04 Licence No: 100017897/2011. Keywords Quaternary, Solway. National Grid Reference SW corner 290000, 550000 Centre point 515000, 570000 The Quaternary Geology NE corner 340000, 590000. Map of the Solway Sheet Solway East and Solway West, 1:50 000 scale, Special Quaternary sheets. A A McMillan, J W Merritt, C A Auton, and N R Golledge Front cover Ice-wedge casts in glaciofluvial sand and gravel sheet deposits of the Kilblane Sand and Gravel Contributors Formation at Halleaths Gravel D C Entwisle, B Humphreys, C J Jordan, B É Ó Dochartaigh, E R Phillips, Pit [NY 0868 8344], Lochmaben. Photo A A McMillan (P774196). and C L Vye Bibliographical reference MCMILLAN, A A, MERRITT, J W, AUTON, C A, and GOLLEDGE, N R. -

Southern Scottish Hill Generics: Testing the Gelling and Cole Hypothesis

Southern Scottish Hill Generics: Testing the Gelling and Cole Hypothesis Peter Drummond University of Edinburgh Gelling and Cole have argued for English hill-names (specifically those incorporated into settlements) that the different generics represent different topographies or shapes all across the land. Their hypothesis is important enough to quote in detail: ... groups of words which can be translated by a single modern English word such as ‘hill’ or ‘valley’ do not contain synonyms. Each of the terms is used for a different kind of hill, valley or whatever ... The key to Anglo-Saxon topographical naming lies in the precise choice of one of the many available words for ... hills ... these names represent a system which operated over most of England ... [except] the south-west peninsula, where English speech arrived several centuries later ...1 Is this true of Scots hill-generics too? Can we have a valid typology of hill-generics applying across southern Scotland, in the way that Gelling and Cole have done for most of England—although their work is on hill toponyms that have been taken into settlement names, by definition lower hills?2 Pratt has attempted a small-scale application of Gelling and Cole’s methodology to settlements in southern Scotland, and her tentative conclusion, on this limited sample, was that their interpreta- tion of six of the nine elements might be supported in this area.3 The nine elements she chose to explore were limited to Old English,4 and 1 M. Gelling and A. Cole, The Landscape of Place-Names (Stamford, 2000), pp. xiii, xiv and xv. -

Land Management Plan Text

1 Criffel Land Management Plan 2017 - 2026 1 1 1 Dumfries and Borders Forest District 1 Criffel 1 Land Management Plan 1 1 1 I J J J J Approval date: *** J Plan Reference No: **** J Plan Approval Date: ***** J Plan Expiry Date: ****** J 1 I Criffel Land Management Plan I Alan Gale 2017 - 2026 J Criffel Land Management Plan 2017 - 2026 FORESTENTERPRISE- Application for Forest Design Plan Approvals in Scotland Forest Enterprise - Property Forest District: Dumfries & Borders Forest District Woodland or property name: Criffel Land Management Plan Nearest town, village or locality: New Abbey as Grid reference: NX96316358 Local Authority district/unitary Dumfries and Borders Areas for approval Conifer Broadleaf Felling 27.8ha Restocking 23.9 3.9 1. I apply for Forest Design Plan approval*/amendment approval* for the property described above and in the enclosed Forest Design Plan. 2. * I apply for an opinion under the terms of the Environmental Impact Assessment (Forestry) (Scotland) Regulations 1999 for afforestation/road building* / quarries* as detailed in my application. 3. I confirm that the initial scoping of the plan was carried out with FC staff in 2016 4. I confirm that the proposals contained in this plan comply with the UK Forestry Standard. 5. I confirm that the scoping, carried out and documented in the Consultation Record attached, incorporated those stakeholders which the FC agreed must be included. 6. I confirm that agreement has been reached with all of the stakeholders over the content of the design plan and that there are no outstanding issues to be addressed. Copies of consultee endorsements of the plan are attached. -

PANORAMA from Grisedale Pike (GR 199226)

PANORAMA from Grisedale Pike (GR 199226) PANORAMA Lord’s Seat Seat How Longlands Fell arm f Binsey Skiddaw Blencathra Ling Fell Broom Fell Overwater Ullock Pike Skiddaw Little Man Great Mell Fell Bothelwind North Pennines 3 AONB 2 7 8 4 5 6 1 Comb Dodd Plantation Latrigg KESWICK Hobcarton End PORTINSCALE 1 Whinlatter 2 Ladies Table 3 Brae Fell BRAITHWAITE 4 Long Side 5 Carl Side 6 Carsleddam Kinn N 7 Bowscale Fell 8 Lonscale Fell E Clough Head Raise Great Rigg High Raise Glaramara Great End Great Dodd Helvellyn Ullscarf Pike o’Stickle Bowfell Scafell Pike Fairfield Causey Pike Eagle Crag Dale Head Esk Pike Great Robinson Crag 1 2 3 4 5 11 12 13 6 7 10 14 Walla Crag Maiden Moor High Spy Hindscarth Derwent Water 8 Scar Crags Barrow 9 Sail Stile End Outerside E 1 Stybarrow Dodd 2 White Side 3 Catstycam 4 Nethermost Pike 5 Dollwaggon Pike 6 Bleaberry Fell 7 High Seat S 8 Catbells 9 Rowling End 10 Grange Fell 11 Harrison Stickle 12 Wetherlam 13 Swirl How 14 Great Gable Kirk Fell Eel Crag Red Pike Grasmoor Sand Hill (Buttermere) Gavel Fell Whiteside Hopegill Head Dove Eel Crags Crag Coledale Hause subsidiary top Hobcarton Crag S Hobcarton Gill valley W ISLE OF WHITHORN DUNDRENNEN Bengairn Screel Hill KIPPFORD DUMFRIES Whinlatter Low F ell F ellbarrow Covend Coast Criffel Caerlaverock Hatteringill Head Solway Firth COCKERMOUTH Graystones Ling Fell Swinside Hobcarton End W Hobcarton Gill valley N This graphic is an extract from The North-Western Fells, volume six in the Lakeland Fellranger series to be published in April 2011 by Cicerone Press Ltd (c) Mark Richards 2010. -

Nith Estuary National Scenic Area Management Strategy

Dumfries and Galloway Council LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2 Nith Estuary National Scenic Area Management Strategy Planning Guidance - November 2019 www.dumgal.gov.uk This management strategy was first adopted as supplementary planning guidance to the Nithsdale Local Plan. That plan was replaced by the Councils first Local Development Plan (LDP) in 2014. The LDP has been reviewed and has been replaced by LDP2 in 2019. As the strategy is considered, by the Council, to remain relevant to the implementation of LDP2 it has been readopted as planning guidance to LDP2. Policy NE1: National Scenic Areas ties the management strategy to LDP2. The management strategy has been produced to ensure the area continues to justify its designation as a nationally important landscape. It provides an agreed approach to the future of the area, offering better guidance and advice on how to invest resources in a more focused way. The Council will work with Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) to review and update the content of the strategy during the lifetime of LDP2. National Scenic Area FOREWORD We are justifiable proud of Scotland’s If we are to ensure that what we value today landscapes, and in Dumfries and Galloway in these outstanding landscapes is retained for we have some of the highest scenic quality, tomorrow, we need a shared vision of their recognised by their designation as National future and a clear idea of the actions required Scenic Areas (NSAs). NSAs represent the very to realise it. This is what this national pilot best of Scotland’s landscapes, deserving of the project set out to do – and we believe this special effort and resources that are required Management Strategy is an important step to ensure that their fine qualities endure, towards achieving it. -

Telescopes, Theodolites and Failing Vision in William Wordsworth's

Journal of Literature and Science Issue 1, Volume 1 (2007) ISSN 1754-646XJournal of Literature and Science 1 (2007) Hewitt, “Eyes to the Blind”: 5-23 Rachel Hewitt, “Eyes to the Blind”: 5-23 ‘Eyes to the Blind’: Telescopes, Theodolites and Failing Vision in William Wordsworth’s Landscape Poetry Rachel Hewitt In 1811, during or shortly after a holiday in the south Cumberland village of Bootle, William Wordsworth drafted a poem about the mountain of Black Combe, which loured over the village. The inscription ‘Written with a Slate Pencil on a Stone, on the Side of the Mountain of Black Combe’ posed as a carving on a rock, on the side of the mountain. It addressed passing climbers, and reminded them of a “geographic Labourer”, a mapmaker, who had ascended to the summit before them. Upon pulling out his map and his topographic sketch-pad at the top of the mountain, darkness fell, and: The whole surface of the out-spread map, Became invisible: for all around Had darkness fallen – unthreatened, unproclaimed - As if the golden day itself had been Extinguished in a moment; total gloom, In which he sat alone, with unclosed eyes, Upon the blinded mountain’s silent top!1 I, Michael Wiley, John Wyatt, and Ron Broglio have all previously placed Wordsworth’s Black Combe Inscription against the background of the Ordnance Survey’s project to create the first complete, accurate map of the United Kingdom. We have independently suggested that this “geographic Labourer” was based upon the figure of William Mudge, who was the director of the Ordnance Survey mapping project between its inception in 1791 and his death in 1818.2 Wordsworth referred to Mudge by name in his Guide to the Lakes as “that experienced surveyor”, and in the unpublished Tour as “the best authority” on Lake District geography.3 There is much evidence that the cartographer of Wordsworth’s inscription was based upon William Mudge. -

4-Night Northern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday

4-Night Northern Lake District Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: DBBOB-4 2, 3 & 5 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Known as the ‘Queen of the Lakes’, Derwent Water’s gentle beauty is easy to explore on our Guided Walking holidays. Surrounded by the picture-postcard valleys of Buttermere and Borrowdale and lofty mountains, the sheer splendour of these landscapes is guaranteed to inspire you. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 3 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the Northern Lake District on foot • Admire panoramic mountain, lake and river views from fells and peaks • Let our experienced leader bring classic routes and offbeat areas to life • Enjoy magnificent Lake District mountainscape scenery and visit charming Lakeland villages • Look out for wildlife, find secret corners and learn about the Lakes’ history • A relaxed pace of discovery in a sociable group keen to get some fresh air in one of England’s most beautiful walking areas TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 2, 3 and 5, Explore the beautiful Lake District on our guided walks. We offer a great range of walks to suit everyone - from gentle lakeside walks, to challenging mountain ridges.