Negotiating Financial Systems and Poverty Alleviation Logics in Microfinance: Macro and Micro Level Dynamics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butcher, W. Scott

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WILLIAM SCOTT BUTCHER Interviewed by: David Reuther Initial interview date: December 23, 2010 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Dayton, Ohio, December 12, 1942 Stamp collecting and reading Inspiring high school teacher Cincinnati World Affairs Council BA in Government-Foreign Affairs Oxford, Ohio, Miami University 1960–1964 Participated in student government Modest awareness of Vietnam Beginning of civil rights awareness MA in International Affairs John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies 1964–1966 Entered the Foreign Service May 1965 Took the written exam Cincinnati, September 1963 Took the oral examination Columbus, November 1963 Took leave of absence to finish Johns Hopkins program Entered 73rd A-100 Class June 1966 Rangoon, Burma, Country—Rotational Officer 1967-1969 Burmese language training Traveling to Burma, being introduced to Asian sights and sounds Duties as General Services Officer Duties as Consular Officer Burmese anti-Indian immigration policies Anti-Chinese riots Ambassador Henry Byroade Comment on condition of embassy building Staff recreation Benefits of a small embassy 1 Major Japanese presence Comparing ambassadors Byroade and Hummel Dhaka, Pakistan—Political Officer 1969-1971 Traveling to Consulate General Dhaka Political duties and mission staff Comment on condition of embassy building USG focus was humanitarian and economic development Official and unofficial travels and colleagues November -

Social Entrepreneurship – Creating Value for the Society Dr

Prabadevi M. N., International Journal of Advance Research, Ideas and Innovations in Technology. ISSN: 2454-132X Impact factor: 4.295 (Volume3, Issue2) Available online at www.ijariit.com Social Entrepreneurship – Creating Value for the Society Dr. M. N. Prabadevi SRM University [email protected] Abstract: Social entrepreneurship is the use of the techniques by start-up companies and other entrepreneurs to develop, fund and implement solutions to social, cultural, or environmental issues. This concept may be applied to a variety of organizations with different sizes, aims, and beliefs. Social Entrepreneurship is the attempt to draw upon business techniques to find solutions to social problems. Conventional entrepreneurs typically measure performance in profit and return, but social entrepreneurs also take into account a positive return to society. Social entrepreneurship typically attempts to further broad social, cultural, and environmental goals often associated with the voluntary sector. At times, profit also may be a consideration for certain companies or other social enterprises. Keywords: Social Entrepreneurship, Values, Society. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Defining social entrepreneurship Social entrepreneurship refers to the practice of combining innovation, resourcefulness, and opportunity to address critical social and environmental challenges. Social entrepreneurs focus on transforming systems and practices that are the root causes of poverty, marginalization, environmental deterioration and accompanying the loss of human dignity. In so doing, they may set up for-profit or not-for-profit organizations, and in either case, their primary objective is to create sustainable systems change. The key concepts of social entrepreneurship are innovation, market orientation and systems change. 1.2 Who are Social Entrepreneurs? A social entrepreneur is a society’s change agent: pioneer of innovations that benefit humanity Social entrepreneurs are drivers of change. -

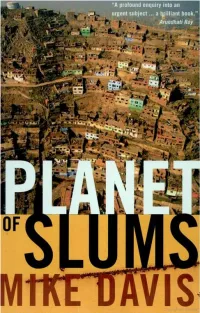

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums

- Planet of Slums • MIKE DAVIS VERSO London • New York formy dar/in) Raisin First published by Verso 2006 © Mike Davis 2006 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 357910 864 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014 -4606 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN 1-84467-022-8 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Garamond by Andrea Stimpson Printed in the USA Slum, semi-slum, and superslum ... to this has come the evolution of cities. Patrick Geddes1 1 Quoted in Lev.isMumford, The City inHistory: Its Onj,ins,Its Transf ormations, and Its Prospects, New Yo rk 1961, p. 464. Contents 1. The Urban Climacteric 1 2. The Prevalence of Slums 20 3. The Treason of the State 50 4. Illusions of Self-Help 70 5. Haussmann in the Tropics 95 6. Slum Ecology 121 .7. SAPing the Third World 151 ·8. A Surplus Humanity? 174 Epilogue: Down Vietnam Street 199 Acknowledgments 207 Index 209 1 The U rhan Climacteric We live in the age of the city. The city is everything to us - it consumes us, and for that reason we glorify it. Onookome Okomel Sometime in the next year or two, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his viJlage in west Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima's innumerable pueblosjovenes . -

Plan for Irrc in G-15 (Islamabad) Ahkmt-E-Guard Initiative

INTEGRATED RESOURCE RECOVERY CENTRE G/15 ISLAMABAD Recycining center Dhaka Bangladesh Presented By Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan Memorial Trust PLAN FOR IRRC IN G-15 (ISLAMABAD) AHKMT-E-GUARD INITIATIVE JKCHS Plan for IRRC Private Initiative 1.5 Kanal land by JKCHS Total 4600 plots 3-5 ton capacity IRRC 2200 HH are residing now UN-Habitat and UNESCAP Secondary collection system provided financial support was not available and waste concern and CCD provided technical support for AHKMT the IRRC Primary collection service is providing to almost 1500 hh through mutual agreement Primary collection will be extended gradually within 5 years PARTNERSHIP ARRANGEMENTS SITUATION IN ISLAMABAD As per survey in 2014 total population is 1.67 million and waste amount was 800 tons p/day Landfill site is still required Secondary collection and waste transportation requires huge funds Recyclables and organic material is not being utilized Mostly Housing societies of Zone II and Zone V have not proper waste collection and disposal system Present Situation Mixed Waste Waste Bins Demountable Transfer Containers Stations Landfill PROBLEMS Water Pollution Spread of Disease Vectors Green House Gas Emission Odor Pollution More Land Required for Landfill What is Integrated Resource Recovery Center (IRRC)? IRRC is a facility where significant portion (80-90%) of waste can be composted/recycled and processed in a cost effective way near the source of generation in a decentralized manner. IRRC is based on 3 R Principle. Capacity of IRRC varies from 2 to -

New Oxford Social Studies for Paksitan

NEW OXFORD SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHING GUIDE FOR PAKISTAN 3 FOURTH EDITION 5 Introduction The New Oxford Social Studies for Pakistan Fourth Edition has been revised and updated both in terms of text, illustrations, and sequence of chapters, as well as alignment to the National Curriculum of Pakistan 2006. The lessons have been grouped thematically under unit headings. The teaching guides have been redesigned to assist teachers to plan their lessons as per their class needs. Key Learning: at the beginning of each lesson provides an outline of what would be covered during the course of the lesson. Background information: is for teachers to gain knowledge about the topics in each lesson. Lesson plans provide a step-by-step guidance with clearly defined outcomes. Duration of each lesson plan is 40 minutes; however, this is flexible and teachers are encouraged to modify the duration as per their requirements. If required, teachers can utilise two periods for a single lesson plan. Outcomes identify what the students will know and be able to do by the end of the lesson. Resources are materials required in the lesson. Teachers are encouraged to arrange the required materials beforehand. In case students are to bring materials from their homes, they should be informed well ahead of time. Introduction of the lesson plan, sets forth the purpose of the lesson. In case of a new lesson, the teacher would give a brief background of the topic; while for subsequent lessons, the teacher would summarise or ask students to recap what they learnt in the previous lesson. The idea is to create a sense of anticipation in the students of what they are going to learn. -

Goodbye Class of 2018 Vardah Qazi, 9B German Teachers Conference

A student publication of Summer Edition The C.A.S. School Vol. 15, Issue # 4: May 2018 Goodbye Class of 2018 Vardah Qazi, 9B Class 6 presentation International football training camp Risa Tohid, 9C Ayesha Bokhari, 6C From 14 to 20 March, Aryan team won a match against Europa On 19 April, students of Class 6 Sulaiman (6A), Yahya Saeed Khan International School, even though it performed the musical, Matilda based (8B) and Ramis Riaz Kamlani (8A) was snowing. We also watched a live on the book by Roald Dahl. The story and I attended an international match of the FC Barcelona team. It is about a girl who loves to read and football training camp in Barcelona, was an unforgettable experience. is born with astonishing intelluctual Spain through the Karachi United abilities and the power of telekinesis. Academy. Students from six schools We were all divided into the cast, of Karachi attended the camp where dancers and the choir, ensuring that we trained with the official coaches everyone was given an opportunity of the FC Barcelona Academy and to participate. The character of played matches against junior football Matilda was played by four different teams. We were able to improve our students. On 18 April we had a dress football skills and learn the rehearsal and performed for our importance of teamwork. The girls’ The annual graduation ceremony for former President of the Student grandparents and siblings. The the Class of 2018 was held on Government, Ayrah Shoaib Khan, rehearsal also helped us prepare for 21 April. The event was attended by delivered her welcome address. -

Dr Akhtar Hameed Khan Profile

MIMAR 34 27 RURAL DEVELOPMENT DR AKHTAR HAMEED KHAN PROFILE <.:l .: ;:i 0.. Z .: > :.: u Z highlight of a recent seminar It was Dr. Khan who pointed out the houses built on two sides of a road - the for journalists was a meeting, floods were not caused by rain, but rather basic unit of social organization. Each A in Karachi, with Dr. Akhtar by the breakdown of the feudal system lane, in effect, became a co-operative led Hameed Khan. The setting whose institutions had ensured the by two elected lane managers responsible was Orangi Township, part of a vast drainage system was maintained. for applying to the OPP for advice, unauthorized settlement, where Dr. Khan Furthermore, he argued, the state couldn't collecting money, calling meetings, runs the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) - a function as a feudal system. The only organizing labour. The lane unit was small brilliant, grass-roots, self-help programme solution lay in organizing the peasants, enough to allow for making community predicated on the conviction that no thereby creating new institutions to contacts, and to circumvent local change is possible without social change. replace the old. This led to his councillors whose administrative unit is Announced as a cultural hybrid, he talked involvement in rural development, and the the neighbourhood or sector. about his life and times, occasionally formation of the Comilla Academy. Dr. quoting Aristotle and St. Augustine, Khan put it very simply: "God made me "Here is a new pattern," said Dr. Khan. punctuating his conversation with contemplative. I insist on action, not just "For the first time, poor people are being summary bullets: "People like me, today, contemplation." guided by highly qualified people. -

The Microfinance Illusion Milford Bateman

‘Why Doesn’t Microfinance Work? The Destructive Rise of Local Neoliberalism’ Milford Bateman Research Fellow, Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London Book launch presentation ODI London July 5th, 2010 The birth of Microfinance [MF] in late 1970s Bangladesh… • Long history of small-scale credit in India, Pakistan and then Bangladesh – Akhtar Hameed Khan’s ‘Comilla model’ • In late 1970s Dr Muhammad Yunus sees microcredit examples and develops his own model - pitches it to the donor community • Grameen Bank formally established in 1983 to lend to the poor for income-generating activities (IGAs) • ‘Poverty will be eradicated in a generation (and) our children will have to go to a “poverty museum” to see what all the fuss was about…’ • International donors love the non-state, self-help, fiscally responsible, and individual entrepreneurship angles • Supposedly high repayment rates in Grameen Bank (much exaggeration later found) mean the poor seen as ‘bankable’ Washington DC institutions insist on a few changes… • In 1980s policymakers in World Bank and US government pushing the mantra of ‘full cost recovery’ • Hard-line belief is that the poor must pay the FULL costs of any program ostensibly designed to help them • MF to be no exception….MF is neoliberalised... • CGAP and USAID appointed to take lead in imposing the ‘New Wave’ MF model that replaces the Grameen Bank as ‘preferred practise’ • Key methodology to impose high interest rates and Wall Street-style rewards (high salaries, bonuses, share options) which should lead to maximum efficiency But by late 2000’s MF begins to run into a host of problems • By early 2000s MF increasingly becomes clear that MF ‘all talk and no walk’ - poverty not actually seen to be reduced anywhere • More scope to critically analyse what accomplishments have really been made.... -

Case Studies on the Orangi Pilot Project (Sanitation)

Whose Public Action? Analysing Inter-sectoral Collaboration for Service Delivery Pakistan Sanitation Case Study: Orangi Pilot Project-Research Training Institute’s (OPP-RTI’s) relationship with government agencies Dr Masooda Bano Islamabad, Pakistan February 2008 Published: February 2008 (c) International Development Department (IDD) / Masooda Bano ISBN: 0704426692 9780704426696 This research is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council under the ESRC Non- Governmental Public Action Programme. The ESRC is the UK’s leading research and training agency addressing economic and social concerns. ESRC aims to provide high- quality research on issues of importance to business, the public sector and Government. 1 2 1. Introduction This report provides an understanding of the evolution and nature of the relationship between OPP and the Karachi City Government (KCG) and the Karachi Water and Sewage Board (KWSB) to improve access to sanitation facilities for poor communities. The report attempts to identify the key factors shaping the relationship and whether and how the relationship has influenced the working or agendas of the participating organisations. 1.1. Methodology The information and analysis provided in this report is based on documentary evidence, in-depth interviews with staff within the NSP and the relevant government agencies and the observation of the realities witnessed during the fieldwork conducted with the NSP and the relevant state agencies during November 2006 to September 2007. The report also draws upon analysis of the evolution of the state-NSP relationship in Pakistan and the programme analysis for each sector conducted during stage 2 of this research project. Drawing on those reports was important to identify the over all conditioning factors shaping the relationship under study. -

Social Entrepreneurship Before Neoliberalism? the Life and Work of Akhtar Hameed Khan

Working Paper Series January 2019 Social entrepreneurship before neoliberalism? The life and work of Akhtar Hameed Khan Working Paper 02-19 David Lewis David Lewis LSE Department of Social Policy The Department of Social Policy is an internationally recognised centre of research and teaching in social and public policy. From its foundation in 1912 it has carried out cutting edge research on core social problems, and helped to develop policy solutions. The Department today is distinguished by its multidisciplinarity, its international and comparative approach, and its particular strengths in behavioural public policy, criminology, development, economic and social inequality, education, migration, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and population change and the lifecourse. The Department of Social Policy multidisciplinary working paper series publishes high quality research papers across the broad field of social policy. Department of Social Policy London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE Email: [email protected] Telephone: +44 (0)20 7955 6001 lse.ac.uk/social-policy Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. To cite this paper: Lewis, D (2019), Social Entrepreneurship before neoliberalism? The life and work of Akhtar Hameed Khan, Social Policy Working Paper 02-19, London: LSE Department of Social Policy. Social Policy Working Paper 02-19 Abstract The life history method can be used to historicise the study of social and public policy. Reviewing the life and work of Pakistani social entrepreneur A.H. Khan provides a useful reminder that what Jyoti Sharma recently termed ‘the neoliberal takeover of social entrepreneurship’ is a relatively recent phenomenon. -

K-Electric Holds Pride of Karachi Awards Ceremony at Mohatta Palace

Formerly: Karachi Electric Supply Company (KESC) Quarterly E-Newsletter 20th Edition Special Edition 2014 website: www.ke.com.pk Page - 01 K-ELECTRIC HOLDS PRIDE OF KARACHI AWARDS CEREMONY AT MOHATTA PALACE K-Electric Limited (KE), formerly known as Karachi Electric scape. Supply Company Limited (KESC), on the completion of its 100 The Award Ceremony was hosted at the Palace which dates years, held the ‘KE Pride of Karachi Awards’ at the historical back to 1927. It was a humble attempt to recognize and honor Mohatta Palace, where the honorable Governor of Sindh, Dr. those individuals who have worked selflessly and passionately Ishratul Ibad presided as the Chief Guest. for the betterment of this society. Individuals from the fields of KE has been an integral part of Karachi for over 100 years, Arts and Architecture, Literature, Performing and Visual Arts serving more than 20 million consumers and employing over and Sports and Social Work had been shortlisted and selected 11,000 residents of Karachi. Having completed this milestone, by an honorable council. The chief guest, Dr.Ishratul Ibad ap- KE is even more committed to working towards the better- preciated the award ceremony for recognizing the services of ment of this glorious city. Being so deeply engrained in the the 25 people who won the ‘KE Pride of Karachi Awards’. fabric of Karachi, KE decided to conduct an awards ceremony The winners have also been awarded a lifetime supply of ‘Free’ to commemorate the rich history of the city by paying tributes electricity from KE. Dr. Ishratul Ibad also asked the KE leader- to individuals from all walks of life. -

S.No Author Title of the Book Publication House 1 Abdul Sattar

S.No Author Title of the book Publication House English Non-Fiction 1 Abdul Sattar Pakistan's Foreign Policy 1947-2012 Oxford 2 Abu Bakar Amin Bajwa Inside Waziristan Vanguard Books Born to Lead: The Life and Times of S.M. 3 Adil Ahmed Afeef Group Muneer 4 Ayesha Jalal The Pity of Partition Oxford 5 Azmat Wali Conspiracy Against Islam Royal Book Company 6 Dr. Asrar H. Siddiqui Bankers' Practical Advances Royal Book Company 7 Dr. Farakh A. Khan Murree During The Raj Le Topical Dr. Mahmood Daram & Marziyeh S 8 Shakespeare and Nezami Iqbal Academy Ghoreishi 9 Dr. Manzoor Ahmad Islam and Contemporary Perspective Royal Book Company The All India Muslim League and Allama 10 Dr. Nadeem Shafiq Malik Iqbal Academy Iqbal's Allahabad Address, 1930 The 19th Century Indian Feudatory State 11 Iqbal Nanjee Pakistan Post Foundation Jammu & Kashmir The Politics of Pakistan: Role of the 12 Kausar Parveen Oxford Opposition 13 Khayyam Durrani Naked I- Memoirs of a Humanist Royal Book Company 14 Lt. Col. Mahmood Ahmed Ghazi Afghan war and The Stinger Saga Nadeem printers A History of the All-India Muslim League 15 M. Rafique Afzal Oxford 1906-1947 Pakistan Heritage Preservation & 16 Momin Bullo Hyderabad Revisted Promotion Society 17 Mrs. Rizwan Khan Swimming Between The Sharks Ferozsons (Pvt) Limited 18 Muhammad Nadeem Butt Taking Charge of Public Administration Institute of Public Health, Quetta 19 Muhammad Tahir Books That Changed My Life National Book Founation 20 Musa Khan Jalalzai Punjabi Taliban Royal Book Company Aboard the Democracy Train: A Journey 21 Nafisa Hoodbhoy Through Pakistan Last Decade of Paramount Books (Pvt) Ltd.