2021 CCPS Women's History Month

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

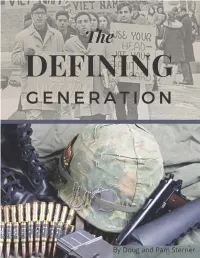

The Defining Generation

The Defining Generation By Doug and Pam Sterner "Even this evil is productive of good. It prevents the degeneracy of government and nourishes a general attention to the public affairs. "I hold that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical." Thomas Jefferson In a letter to James Madison regarding Shay's Rebellion This electronic book is available for free download and printing from www.homeofheroes.com. You may print and distribute in quantity for all non-profit, educational purposes. Copyright 2018 by Legal Help for Veterans, PLLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Introduction Since the birth of our nation in 1776, no single generation of Americans has been spared the responsibility of defending freedom by force of arms. In 1958 the first small American unit visited the land known as Vietnam. It wasn't until 1975 that the last troops assisted the Vietnamese evacuation process. Over 9,800,000 US troops served in Vietnam and more than 58,000 were lost. Many died after the war from wounds, the effects of Agent Orange and PTSD. Some suffer to this day. Most have gone on to become productive citizens. It has always been popular throughout our Nation’s short history to take wars and somehow, for posterity sake, condense them down into some catchy title and memorable synopsis. World War I was known as "The War to End All Wars". It wasn't! Twenty-three years after the Doughboys returned home a new generation of Americans was confronted with the likes of Normandy, Guadalcanal, and Iwo Jima. -

The Dichotomy Between British and American Women Auxiliary Pilots of World War II

Straighten Up and Fly Right: The Dichotomy between British and American Women Auxiliary Pilots of World War II Brighid Klick A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 31, 2014 Advised by Professor Kali Israel TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Military Services and Auxiliaries ................................................................................. iii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: Introduction of Women Pilots to the War Effort…….... ..................... 7 Chapter Two: Key Differences ..................................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: Need and Experimentation ................................................................ 65 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................... 91 Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 98 ii Acknowledgements I would first like to express my gratitude to my adviser Professor Israel for her support from the very beginning of this project. It was her willingness to write a letter of recommendation for a student she had just met that allowed -

Navigating Discrimination

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Educational Policy Studies Dissertations Department of Educational Policy Studies Spring 5-16-2014 Navigating Discrimination: A Historical Examination of Womens’ Experiences of Discrimination and Triumph within the United States Military and Higher Educational Institutions Dackri Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss Recommended Citation Davis, Dackri, "Navigating Discrimination: A Historical Examination of Womens’ Experiences of Discrimination and Triumph within the United States Military and Higher Educational Institutions." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss/110 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Educational Policy Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Policy Studies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, NAVIGATING DISCRIMINATION: A HISTORICAL EXAMINATION OF WOMENS’ EXPERIENCES OF DISCRIMINATION AND TRIUMPH WITHIN THE UNITED STATES MILITARY AND HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS, by DACKRI DIONNE DAVIS, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Education, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chair, as representative of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. ______________________ ____________________ Deron Boyles, Ph.D. Philo Hutcheson, Ph.D. Committee Chair Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Megan Sinnott, Ph.D. -

The President's Commission on the Celebration of Women in American

The President’s Commission on Susan B. Elizabeth the Celebration of Anthony Cady Women in Stanton American History March 1, 1999 Sojourner Lucretia Ida B. Truth Mott Wells “Because we must tell and retell, learn and relearn, these women’s stories, and we must make it our personal mission, in our everyday lives, to pass these stories on to our daughters and sons. Because we cannot—we must not—ever forget that the rights and opportunities we enjoy as women today were not just bestowed upon us by some benevolent ruler. They were fought for, agonized over, marched for, jailed for and even died for by brave and persistent women and men who came before us.... That is one of the great joys and beauties of the American experiment. We are always striving to build and move toward a more perfect union, that we on every occasion keep faith with our founding ideas and translate them into reality.” Hillary Rodham Clinton On the occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the First Women’s Rights Convention Seneca Falls, NY July 16, 1998 Celebrating Women’s History Recommendations to President William Jefferson Clinton from the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. Ellen Ochoa, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt, Irene Wurtzel March 1, 1999 Table of Contents Executive Order 13090 ................................................................................1 -

Women's Studies

A Guide to Historical Holdings in the Eisenhower Library WOMEN'S STUDIES Compiled by Barbara Constable April 1994 Guide to Women's Studies at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library While the 1940s may conjure up images of "Rosie the Riveter" and women growing produce in their Victory Gardens on the homefront, the 1950s may be characterized as the era of June Cleaver and Harriet Nelson--women comfortable in the roles of mother and wife in the suburban neighborhoods of that era. The public statements concerning women's issues made by President Dwight D. Eisenhower show him to be a paradox: "...we look to the women of our land to start education properly among all our citizens. We look to them, I think, as the very foundation--the greatest workmen in the field of spiritual development...We have come a long ways in recognizing the equality of women. Unfortunately, in some respects, it is not yet complete. But I firmly believe it will soon be so." (Remarks at the College of Puget Sound, Tacoma, Washington, October 18, 1956) "I cannot imagine a greater responsibility, a greater opportunity than falls to the lot of the woman who is the central figure in the home. They, far more than the men, remind us of the values of decency, of fair play, of rightness, of our own self-respect--and respecting ourselves always ready to respect others. The debt that all men owe to women is not merely that through women we are brought forth on this world, it is because they have done far more than we have to sustain and teach those ideals that make our kind of life worth while." (Remarks at Business and Professional Women Meeting, Detroit, Michigan, October 17, 1960) "Today there are 22 million working women. -

General Files Series, 1932-75

GENERAL FILE SERIES Table of Contents Subseries Box Numbers Subseries Box Numbers Annual Files Annual Files 1933-36 1-3 1957 82-91 1937 3-4 1958 91-100 1938 4-5 1959 100-110 1939 5-7 1960 110-120 1940 7-9 1961 120-130 1941 9-10 1962 130-140 1942-43 10 1963 140-150 1946 10 1964 150-160 1947 11 1965 160-168 1948 11-12 1966 168-175 1949 13-23 1967 176-185 1950-53 24-53 Social File 186-201 1954 54-63 Subject File 202-238 1955 64-76 Foreign File 239-255 1956 76-82 Special File 255-263 JACQUELINE COCHRAN PAPERS GENERAL FILES SERIES CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents Subseries I: Annual Files Sub-subseries 1: 1933-36 Files 1 Correspondence (Misc. planes) (1)(2) [Miscellaneous Correspondence 1933-36] [memo re JC’s crash at Indianapolis] [Financial Records 1934-35] (1)-(10) [maintenance of JC’s airplanes; arrangements for London - Melbourne race] Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1934 (1)-(7) 2 Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1935 (1)(2) Edmund Jakobi 1934 Re: G.B. Plane Return from England Just, G.W. 1934 Leonard, Royal (Harlan Hull) 1934 London Flight - General (1)-(12) London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables General (1)-(5) [cable file of Royal Leonard, FBO’s London agent, re preparations for race] 3 London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Fueling Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Hangar Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Insurance [London - Melbourne Flight Instructions] (1)(2) McLeod, Fred B. [Fred McLeod Correspondence July - August 1934] (1)-(3) Joseph B. -

Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady Rachel Morris College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Morris, Rachel, "Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 289. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in American Studies from the College of William and Mary in Virginia. Rachel Diane Morris Accepted for ________________________________ _________________________________________ Timothy Barnard, Director _________________________________________ Chandos Brown _________________________________________ Susan Kern _________________________________________ Charles McGovern 2 Table of -

Press Conference at the National Women's Hall of Fame of Hon

10-07-00: PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL...NET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES NEW YORK PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL OF FAME OF HON. JANET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES Saturday, October 7, 2000 New York Chiropractic College Athletic Center 2360 State Route 89 Seneca Falls, New York 9:38 a.m. P R O C E E D I N G S CHAIR SANDRA BERNARD: Good morning and welcome to the National Women's Hall of Fame Honors Weekend and Induction Ceremony. I am Sandra Bernard, Chair of the weekend's events. Today, before a sell-out crowd, we will induct 19 remarkable women into the Hall of Fame. Now, those of you who are history buffs may know that the idea to form a Hall to honor, in perpetuity, the contributions to society of American women started, like so many other good things in Seneca Falls have, over tea. And just like the tea party that spawned the Women's Rights Convention, the concept of a National Women's Hall of Fame was an idea whose time has come. http://www.usdoj.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2000/10700agsenecafalls.htm (1 of 11) [4/20/2009 1:10:27 PM] 10-07-00: PRESS CONFERENCE AT THE NATIONAL WOMEN'S HALL...NET RENO ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES NEW YORK Our plans for the morning are to tell you a bit more about the mission, the moment and the meaning, and then to introduce you to the inductees. -

Jacqueline Cochran Crossword Manufacturing Beauty Products

Jacqueline Cochran acqueline Cochran is one of the most famous women in aviation history. She learned to y in only J three weeks. She later broke an existing altitude record by ying a biplane to 33,000 feet in the air. Jacqueline became very interested in air racing and participated in several races including the Bendix Cross Country Air Race. She had to convince Mr. Bendix to allow her to y since the race had been open to men pilots only. She won the race in 1937. Jacqueline also won speed records for ying. The most famous record she holds for speed was when she became the rst woman to break the sound barrier in 1953. She was named “the fastest woman in the world.” Before learning to y she had worked for several years in a beauty shop. She later began a company Jacqueline Cochran Crossword manufacturing beauty products. She named her company Jacqueline Cochran Cosmetics. When World War II began, Jacqueline was involved in testing new aviation equipment being devel- oped for the war. She also had the idea the military should include women as pilots during the war. acqueline Cochran is one of the most famous women in aviation history. She learned to fly in only After several meetings with the Chief of the Army Air Force General Hap Arnold , she was able to three weeks. She later broke an existing altitude record by flying a biplane to 33,000 feet in the air. J convince him to use women pilots to y non-combat missions. She became the director of the new Jacqueline became very interested in air racing and participatedorganization in several which races was named including the the Women Airforce Service Pilots ( WASP ). -

![Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6994/biographies-of-women-scientists-for-young-readers-pub-date-94-note-33p-1256994.webp)

Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 548 SE 054 054 AUTHOR Bettis, Catherine; Smith, Walter S. TITLE Biographies of Women Scientists for Young Readers. PUB DATE [94] NOTE 33p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Biographies; Elementary Secondary Education; Engineering Education; *Females; Role Models; Science Careers; Science Education; *Scientists ABSTRACT The participation of women in the physical sciences and engineering woefully lags behind that of men. One significant vehicle by which students learn to identify with various adult roles is through the literature they read. This annotated bibliography lists and describes biographies on women scientists primarily focusing on publications after 1980. The sections include: (1) anthropology, (2) astronomy,(3) aviation/aerospace engineering, (4) biology, (5) chemistry/physics, (6) computer science,(7) ecology, (8) ethology, (9) geology, and (10) medicine. (PR) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** 00 BIOGRAPHIES OF WOMEN SCIENTISTS FOR YOUNG READERS 00 "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Once of Educational Research and Improvement Catherine Bettis 14 EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION Walter S. Smith CENTER (ERIC) Olathe, Kansas, USD 233 M The; document has been reproduced aS received from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve Walter S. Smith reproduction quality University of Kansas TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES Points of view or opinions stated in this docu. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." ment do not necessarily rpresent official OE RI position or policy Since Title IX was legislated in 1972, enormous strides have been made in the participation of women in several science-related careers. -

Jacqueline Cochran Held More Speed, Altitude, and Distance Records Than Any Other Male Or Female Pilot in Aviation History…

¾ Aviation Pioneer ¾ Entrepreneur ¾ Leader ¾ Legend At the time of her death in 1980, Jacqueline Cochran held more speed, altitude, and distance records than any other male or female pilot in aviation history… Jacqueline Cochran’s record book will never…NEVER…be duplicated. GREATEST WOMEN This presentation chronicles “The PILOT!! Aviation Achievements of Ms. Jackie Cochran.” Jackie Cochran’s accomplishments match those of our Airpower legends ¾ Pilot License (1932) ¾ London to Melbourne (1934) ¾ First Bendix Race (1934) ¾ Accidents? . Yes! ¾ Discouraged? . No! Bendix Trophy... 1938 Harmon Trophy ¾ 1937 ¾ 1938 ¾ 1939 ¾ 1940-49 ¾ 1953 ¾ 1961 Test Pilot 1938-1942 ¾ P-38 ¾ P-47 ¾ P-51 ¾ B-17 ¾ British Air Transport Auxiliary (1941) ¾ President, “Ninety-Nines” (1941-1943) Director, US Women’s Flying Training… September 1942 Trained 1800 women for flight duty during WWII ¾ Founder/Director Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs)… July 1943 ¾ French Legion of Merit (1949) ¾ French Air Medal (1951) ¾ Decorated by 25 nations ¾ First Woman to break the Sound Barrier… ¾ 18 May 1953 ¾ First Woman to Land and then Take Off from an Aircraft Carrier ¾ A3D Skywarrior on USS Independence… 1960 ¾ President-Federation Aeronautique‘ Internationale (1958-61) ¾ Chairman-National Aeronautic Association (1962) ¾ First Woman to fly twice the speed of sound…3 June 1964 1429 nautical miles per hour!! ¾ World Altitude Record… 1961 55,253 feet!! ¾ Air Force Academy… 1975 National Aviation Hall of Fame (1971) Smithsonian (1981) Motorsports Hall of Fame (1993) Colonel in USAF Reserve Distinguished Service Medal (1945) Distinguished Flying Cross w/2 Oak Leaf Clusters (May 1969) Legion of Merit (1970) Additional Achievements Cosmetics Business (1932) Politics (1946) Frank M. -

Page 01 0F37 Withheld Pursuant to Exemption Non Responsive Record

Page 01 0f37 Withheld pursuant to exemption Non Responsive Record of the Freedom of Information Page 02 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) ; (b)(6) of the Freedom of Information Page 03 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) ; (b)(6) of the Freedom of Information Page 04 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) ; (b)(6) of the Freedom of Information Page 05 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) ; (b)(6) of the Freedom of Information Page 06 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) ; (b)(6) of the Freedom of Information Page 07 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) of the Freedom of Information Page 08 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) of the Freedom of Information DAILY BRIEFING BOOK Wednesday, March 4, 2020 SECRETARY ROBERT L. WILKIE 7:45 - 8:15 am Daily Sync Mtg SEC VA Suite HVAC Hearing AAR & Prep for HAC Hearing 8:30 - 9:30 am OBCR MilConVA Hearing Binder ERT Rayburn 2362B 10:00 - 10:30 am ** COS will accompany Rayburn 10:30- 1:00 pm HAC MilConVA Budget Hearing 2362B 1:00 - 1:30 pm ERT VACO 2:00 - 2:30 pm Coronavirus Update w/ Dr. Stone SEC VA Suite ( 4:00 - 4:30 pm ERT White Housem(6) White House Coronavirus Task Force 4:30 - 5:30 pm Principals Mtg ET Hyatt Regency on Capitol Hill 5:30 - 6:00 pm 400 New Jersey Ave, NW _ REMARKS: VFW Legislative Reception & Hyatt 6:00 - 8:00 pm Awards Presentation Regency 8:00 pm ERT Residence 4/1/2020 11:34 AM 9 of 37 Page 10 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) ; (b)(6) of the Freedom of Information Page 11 of 37 Withheld pursuant to exemption (b)(5) ; (b)(6) of the Freedom of Information (b)(6) (b)(6) From: Sent: Friday, February 28, 2020 1:46 PM To: RLW Cc: (b)(6) Powers, Pamela; Syrek, Christopher D.