James Perry and the French Constitution Ceremony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old New Journalism?

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The development and impact of campaigning journal- ism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40128/ Version: Full Version Citation: Score, Melissa Jean (2015) The development and impact of campaigning journalism in Britain, 1840-1875 : the old new journalism? [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London The Development and Impact of Campaigning Journalism in Britain, 1840–1875: The Old New Journalism? Melissa Jean Score Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I, Melissa Jean Score, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signed declaration_________________________________________ Date_____________________ 3 Abstract This thesis examines the development of campaigning writing in newspapers and periodicals between 1840 and 1875 and its relationship to concepts of Old and New Journalism. Campaigning is often regarded as characteristic of the New Journalism of the fin de siècle, particularly in the form associated with W. T. Stead at the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s. New Journalism was persuasive, opinionated, and sensational. It displayed characteristics of the American mass-circulation press, including eye-catching headlines on newspaper front pages. The period covered by this thesis begins in 1840, with the Chartist Northern Star as the hub of a campaign on behalf of the leaders of the Newport rising of November 1839. -

James Perry and the Morning Chronicle 179O—I821

I JAMES PERRY AND THE MORNING CHRONICLE- 179O—I821 By l yon Asquith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1973 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Preface 5 1. 1790-1794 6 2. 1795-1 805 75 3. 1806-1812 (i) ThB Ministry of the Talents 184 (ii) Reform, Radicalism and the War 1808-12 210 (iii) The Whigs arid the Morning Chronicle 269 4. Perry's Advertising Policy 314 Appendix A: Costs of Production 363 Appendix B: Advertising Profits 365 Appendix C: Government Advertisements 367 5. 1813-1821 368 Conclusion 459 Bibliography 467 3 A BSTRACT This thesis is a study of the career of James Perry, editor and proprietor of the Morning Chronicle, from 1790-1821. Based on an examination of the correspondence of whig and radical polit- icians, and of the files of the morning Chronicle, it illustrates the impact which Perry made on the world of politics and journalism. The main questions discussed are how Perry responded, as a Foxite journalist, to the chief political issues of the day; the extent to which the whigs attempted to influence his editorial policy and the degree to which he reconciled his independence with obedience to their wishes4 the difficulties he encountered as the spokesman of an often divided party; his considerable involvement, which was remarkable for a journalist, in party activity and in the social life of whig politicians; and his success as a newspaper proprietor concerned not only with political propaganda, but with conducting a paper which was distinguished for the quality of its miscellaneous features and for its profitability as a business enterprise. -

Copyright at Common Law in 1774

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2014 Copyright at Common Law in 1774 H. Tomas Gomez-Arostegui Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Gomez-Arostegui, H. Tomas, "Copyright at Common Law in 1774" (2014). Connecticut Law Review. 263. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/263 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 47 NOVEMBER 2014 NUMBER 1 Article Copyright at Common Law in 1774 H. TOMÁS GÓMEZ-AROSTEGUI As we approach Congress’s upcoming reexamination of copyright law, participants are amassing ammunition for the battle to come over the proper scope of copyright. One item that both sides have turned to is the original purpose of copyright, as reflected in a pair of cases decided in Great Britain in the late 18th century—the birthplace of Anglo-American copyright. The salient issue is whether copyright was a natural or customary right, protected at common law, or a privilege created solely by statute. These differing viewpoints set the default basis of the right. Whereas the former suggests the principal purpose was to protect authors, the latter indicates that copyright should principally benefit the public. The orthodox reading of these two cases is that copyright existed as a common-law right inherent in authors. In recent years, however, revisionist work has challenged that reading. Relying in part on the discrepancies of 18th-century law reporting, scholars have argued that the natural-rights and customary views were rejected. -

Choking the Channel of Public Information: Re-Examination of an Eighteenth-Century Warning About Copyright and Free Speech

CHOKING THE CHANNEL OF PUBLIC INFORMATION: RE-EXAMINATION OF AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY WARNING ABOUT COPYRIGHT AND FREE SPEECH EDWARD L. CARTER* The U.S. Supreme Court in Eldred v. Ashcroft gave First Amendment importance to the topic of copyright history. In measuring whether Congress has altered the “traditional contours” of copyright such that First Amendment scrutiny must be applied, federal courts—including the Supreme Court in its 2011 Term case Golan v. Holder—must carefully examine the intertwined history of copyright and freedom of the press. The famous but misunderstood case of Donaldson v. Beckett in the British House of Lords in 1774 is an important piece of this history. In Donaldson, several lawyers, litigants, judges, and lords recognized the danger posed by copyright to untrammeled public communication. Eighteenth-century newspaper accounts shed new light on the free press implications of this important period in copyright law history. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................80 I. SCHOLARLY VIEWS ON DONALDSON V. BECKETT .......................................84 II. ALEXANDER DONALDSON AND THE CRUSADE AGAINST SPEECH MONOPOLY ................................................................................................91 III. DONALDSON V. BECKETT RE-EXAMINED ....................................................97 A. Day 1: Friday, February 4, 1774 ...................................................99 B. Day 2: Monday, February 7, 1774 ..............................................103 -

John Bramwell Taylor Collection

John Bramwell Taylor Collection Monographs, Articles and Manuscripts 178B27 Photographs and Postcards 178C95 Correspondence 178F27 Notebooks 178P7 Handbills 178T1 Various 178Z42 178B27.1 Taylor of Ightham family tree Pen and ink document with multiple annotations 1p. John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178B27.2 Brookes Family Tree Pen document 1p. John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178C95.1 circa 100 black and white personal, family and holiday photographs John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178F27.1 1 box of letters John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178P7.1 4 notebooks containing hand written poems and other personal thoughts John Bramwell Taylor Collection Egyptian Hall - Piccadilly (see also 178T1.194 and 178T1.156) Ref: 178T1.1 Title: The Wild Man of the Prairies or "What is it"? Headline Act: Wild Man Location: Egyptian Hall - Piccadilly Show Type: Oddities/Curious Event Date: 1846 Folio: 4pp Item size: 127mm x 188mm Printed by: Francis, Printer, 25, Museum Street, Bloomsbury Other Information: Is it Human? Is it an animal? Is it an extraordinary freak of nature? Missing link between man and Ourang-Outang. Flyer details savage living habits, primarily eating fruit and nuts but occasionally must be given a meal of RAW MEAT. ‘Not entirely domesticated tho not averse to exhibition.’ See The Era (London, England), Sunday, August 30, 1846 1 Ref: 178T1.2 Title: Living Ourang Outans! Headline Act: Ourang Outans Location: Egyptian Hall - Piccadilly Show Type: Natural History/Animal Event Date: c1830s Folio: 1pp Item size: 185mm x 114mm Printed by: None given Other information: Male & Female Ourang Outans, One from Borneo - other from River Gambia. "Connecting link between man and the brute creation". -

Download Free to View British Library Newspapers List 9 August 2021

Free to view online newspapers 9 August 2021 Below is a complete listing of all newspaper titles on the British Library’s initial ‘free to view’ list of one million pages, including changes of title. Start and end dates are for what is being made freely available, not necessarily the complete run of the newspaper. For a few titles there are some missing issues for the dates given. All titles are available via https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. The Age (1825-1843) Alston Herald, and East Cumberland Advertiser (1875-1879) The Argus, or, Broad-sheet of the Empire (1839-1843) The Atherstone Times (1879-1879), The Atherstone, Nuneaton, and Warwickshire Times (1879-1879) Baldwin's London Weekly Journal (1803-1836) The Barbadian (1822-1861) Barbados Mercury (1783-1789), Barbados Mercury, and Bridge-town Gazette (1807-1848) The Barrow Herald and Furness Advertiser (1863-1879) The Beacon (Edinburgh) (1821-1821) The Beacon (London) (1822-1822) The Bee-Hive (1862-1870), The Penny Bee-Hive (1870-1870), The Bee-Hive (1870-1876), Industrial Review, Social and Political (1877-1878) The Birkenhead News and Wirral General Advertiser (1878-1879) The Blackpool Herald (1874-1879) Blandford, Wimborne and Poole Telegram (1874-1879), The Blandford and Wimbourne Telegram (1879-1879) Bridlington and Quay Gazette (1877-1877) Bridport, Beaminster, and Lyme Regis Telegram and Dorset, Somerset, and Devon Advertiser (1865, 1877-1879) Brighouse & Rastrick Gazette (1879-1879) The Brighton Patriot, and Lewes Free Press (1835-1836), Brighton Patriot and South of -

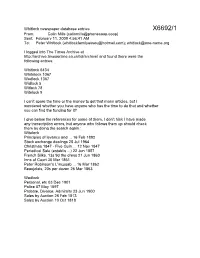

X6692/1 From: Colin Mills ([email protected]) Sent: February 11, 2009 4:56:41 AM To: Peter Whitlock ([email protected]); [email protected]

Whitlock newspaper database entries X6692/1 From: Colin Mills ([email protected]) Sent: February 11, 2009 4:56:41 AM To: Peter Whitlock ([email protected]); [email protected] I logged into The Times Archive at http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/tol/archive/ and found there were the following entries: Whitlock 6434 Whitelock 1067 Wedlock 1367 Widlock 5 Witlock 78 Witelock 9 I can't spare the time or the money to get that many articles, but I wondered whether you have anyone who has the time to do that and whether you can find the funding for it? I give below the references for some of them, I don't hink I have made any transcription errors, but anyone who follows them up should check them by doing the search again.: Witelock Principles of levancy and ... 16 Feb 1892 Stock exchange dealings 25 Jul 1964 Christmas 1847 - Five Guin ... 12 Nov 1847 Periodical Sale (establis ...) 22 Jun 1857 French Silks, 13s 9d the dress 21 Jun 1860 Inns of Court 30 Mar 1861 Peter Robinson's L'incusab ... 16 Mar 1862 Beaujolais, 20s per dozen 26 Mar 1863 Wedlock Personal, etc 03 Dec 1901 Police 07 May 1897 Probate, Divorce, Admiralty 23 Jun 1900 Sales by Auction 26 Feb 1813 Sales by Auction 10 Oct 1818 I also have access to the database of 19th Century Newspapers X6692/2 (accessible to me in the Open University Library via the British Library) Whitlock 4061 Whitelock 3535 Wedlock 6292 Widlock 9 Witlock 68 Witelock 25 References for Witelock: Sunday and Tuesday's Post, The Derby Mercury (Derby), Thu 19 Nov 1807, no 3939 Advertisements -

Canadian Newspapers in English –

Canadian newspapers in English – Click on name of Province to go to that table in this pdf document – View map of Canada Postal # of Flag Shield Province Capital abbreviation newspapers Ontario ON Toronto 93 Quebec QC Quebec City 198 Nova Scotia NS Halifax 19 New Brunswick NB Fredericton 17 Manitoba MB Winnipeg 5 British Columbia BC Victoria 18 Prince Edward Island PE Charlottetown 4 Saskatchewan SK Regina 10 Alberta AB Edmonton 9 Newfoundland and Labrador NL St. John's 9 Northwest Territory 3 Yukon Territory 4 Other Locations 1 Back to top Canadian newspapers in English – Click on newspaper name to go to that Google News Archive newspaper collection Alberta - 9 Back To Top Calgary, Alberta Calgary, Alberta Calgary, Alberta Calgary, Alberta The Calgary Daily The Calgary Herald The Calgary Weekly The Daily Herald Herald 11,686 issues Herald 1,103 issues 7,750 issues May 1, 1929 - Jan 10, 1987 216 issues Jul 4, 1900 - Sep 30, 1907 Sep 8, 1888 - Nov 5, 1948 Jan 11, 1888 - Aug 17, 1894 Edmonton, Alberta Edmonton, Alberta Lethbridge, Alberta Lethbridge, Alberta Edmonton Journal Edmonton Journal The Lethbridge News The Semi-Weekly News 3,820 issues Edmonton Bulletin 700 issues 119 issues Jan 1, 1913 - Dec 20, 1986 40 issues Mar 5, 1886 - Dec 27, 1900 Jan 13, 1891 - Dec 28, 1892 Sep 3, 1946 - Oct 31, 1946 Calgary, Alberta The Weekend Herald 208 issues Jan 7, 1897 - Sep 20, 1982 Canadian newspapers in English – Click on newspaper name to go to that Google News Archive newspaper collection British Columbia - 18 Back To Top New Westminster , B. -

Newspaper Collection Index

Revised 5/6/10 by Tiffani Zalinski Newspaper Collection Index Drawer: The Albany Argus (NY) – Alexander’s Messenger (PA) The Albany Argus (NY): May 9, 1823; July 8, 1823; August 17, 1833; August 23, 1833 The Albion (NY): August 23, 1807 (includes Monthly Review, July 1807); September 20, 1834; September 27, 1834; September 5, 1835; September 26, 1835; February 6, 1836; January 9, 1841; February 13, 1841; March 20, 1841; May 8, 1841; May 15, 1841; June 5, 1841; November 13, 1841; January 15, 1842; June10, 1843; December 16, 1843 Alexander’s Messenger (Philadelphia, PA)): March 6, 1844; February 11, 1846; February 18, 1846; August 4, 1847; January 19, 1848 Drawer: American Courier (PA) – Boston Semi-Weekly Advertiser (MA) Folder 1: American Courier (PA) – Bedford Gazette (PA) American Courier (Philadelphia, PA): June 3, 1848; August 4, 1849; April 3, 1852; September 25, 1852; June 14, 1856 The American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia, PA): July 14, 1830; April 25, 1833 **SEE ALSO Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser, Dunlap and Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser American Masonick Record (Albany, NY): November 14, 1829 The American Mercury (Hartford, CT): March 31, 1788; September 26, 1799 American Republican and Chester County Democrat (West Chester, PA): January 20, 1835 American Sentinel (Philadelphia, PA): October 30, 1834 Andover Townsman (MA): December 20, 1895 Anti-Masonic Telegraph (Norwich, NY): August 29, 1832 Atkinson’s Evening Post (Philadelphia, PA): August 31, 1833; April 30, 1836; February 24, 1838; February 9, 1839; October -

19Th Century British Library Newspapers 17Th and 18Th Century Burney Collection Newspapers

Burney Collection These collections are brought to you by Users will have quick access to Burney’s newspapers and news Gale, through an exclusive partnership pamphlets from a wide-range of news sources including more than with the British Library. 38,000 pages from the London Evening Post, early issues of the Boston and Virginia Gazettes, plus countless journals and annuals. The online pages date as far back as 1603 and continue through to Coverage includes everything from well- the early 19th century. A sampling of the 1,270 titles included are: known historic events and cultural icons 19th Century British Library Newspapers of the time – to sporting events, arts, Athenian Gazette or Casuistical Mercury, 1691 culture and other national pastimes. Bath Chronicle, 1784 th th Some of the most popular newspapers 17 and 18 Century Burney Collection Newspapers include: Daily Courant, 1702 brought to you by Gale, publisher of The Times Digital Archive Daily Gazetteer, 1735 • Daily News • Morning Chronicle Daily Post, 1719 • Illustrated Police News Dublin Mercury, 1769 • The Chartist Grub Street Journal, 1730 • The Era • The Belfast News–Letter London Evening Post, 1727 • The Caledonian Mercury London Gazette, 1666 • The Aberdeen Journal Mercurius Politicus Comprising the Summ of All Intelligence, 1650 Ask us about these related digital collections: • The Leeds Mercury Morning Chronicle, 1770 th • The Exeter Flying Post The Economist Historical Archive 1843–2003 19 Century U.K. Periodicals: Series 1: New Readerships Morning Post, 1773 The Times Digital Archive, 1785–1985 19th Century U.K. Periodicals: Series 2: Empire New England Courant, 1721 North Briton, 1762 About Gale Digital Collections: Oracle, 1790 These two exciting collections are part of Gale Digital Collections, the world’s largest scholarly primary source online library. -

Defending the Constitution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2000 Defending the Constitution Nicholas M. Wolf College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wolf, Nicholas M., "Defending the Constitution" (2000). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626272. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ha95-9093 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Defending the Constitution A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Nicholas M. Wolf 2000 Approval Sheet This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Auth £ f a / I s ---- James McCord t McArthur Robert Gross Table of Contents Abstract Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Constitutionalism, the French Revolution Debate, the Loyalist Press 4 Chapter 2: Defending the Constitution 33 Conclusion 69 Bibliography 73 Abstract This essay concentrates on three newspapers, the Sun, the True Briton, and the Anti- Jacobin, as published in London between 1793 and 1798. At a time when the French Revolution sparked controversy in Britain, stimulating debate on British ruling systems and social framework, these newspapers were excellent examples of the loyalist point of view. -

Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium, 1770–1790 O'quinn, Daniel

Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium, 1770–1790 O'Quinn, Daniel Published by Johns Hopkins University Press O'Quinn, Daniel. Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium, 1770–1790. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.1868. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/1868 [ Access provided at 3 Oct 2021 03:51 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium 1770– 1790 This page intentionally left blank Entertaining Crisis in the Atlantic Imperium 1770– 1790 daniel o’quinn The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2011 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2011 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Mary land 21218- 4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data O’Quinn, Daniel, 1962– Entertaining crisis in the Atlantic imperium, 1770– 1790 / Daniel O’Quinn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8018- 9931- 7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0- 8018- 9931- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. En glish drama— 18th century— History and criticism. 2. Mascu- linity in literature. 3. Politics and literature— Great Britain— History—18th century. 4. Theater— England—London—History— 18th century. 5. Theater— Political aspects— England—London. 6. Press and politics— Great Britain— History—18th century. 7. United States— History—Revolution, 1775– 1783—Infl uence.