Yankee Abolitionist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Civil War Sesquicentennial Special Events

Published for the Members and Friends IN THIS ISSUE: of the Harpers Ferry David L. Larsen Historical Association Memorial Fund Spring 2012 Update “Harpers Ferry Under Fire” 2012 Civil War Sesquicentennial Published Park Entrance Fees Special Events Increased “Stonewall Stopped: Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign” May 26 – 27 “Prelude to Freedom: The 1862 Battle of Harpers Ferry” September 13 – 15 he National Park Service will com- preceded Abraham Lincoln’s memorate two significant 1862 Civil September 22, 1862 signing of TWar events at Harpers Ferry National His- the Preliminary Emancipation torical Park in 2012. On May 26 and 27 Proclamation which shifted the ranger-led programs will guide visitors purpose of war and ultimately through Union General Rufus B. Saxton’s led to the freedom of four mil- successful defense of Harpers Ferry dur- lion enslaved Americans. ing Stonewall Jackson’s 1862 Shenandoah From September 13 to 15 Valley Campaign. The event, Stonewall this event, Prelude to Freedom: Stopped: Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign, will The 1862 Battle of Harpers also include living history and family/youth Ferry, will feature living his- activities. tory, ranger-led programs, Several events are being planned for family/youth activities, special September to mark the 150th anniversary of hikes, bus tours, lectures, panel Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North. discussions, and book signings. One day following the Battle of South There will also be special Mary- Mountain and just two days before the land Campaign lectures with authors Scott Battle of Antietam, over 12,000 Union Hartwig and Dr. Drew Gilpin Faust. -

The Antietam and Fredericksburg

North :^ Carolina 8 STATE LIBRARY. ^ Case K3€X3Q£KX30GCX3O3e3GGG€30GeS North Carolina State Library Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from State Library of North Carolina http://www.archive.org/details/antietamfredericOOinpalf THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG- Norff, Carof/na Staie Library Raleigh CAMPAIGNS OF THE CIVIL WAR.—Y. THE ANTIETAM AND FREDERICKSBURG BY FEAISrCIS WmTHEOP PALFEEY, BREVET BRIGADIER GENERAL, U. 8. V., AND FORMERLY COLONEL TWTENTIETH MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY ; MEMBER OF THE MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETF, AND OF THE MILITARY HIS- TORICAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS. NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNEE'S SONS 743 AND 745 Broadway 1893 9.73.733 'P 1 53 ^ Copyright bt CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1881 PEEFAOE. In preparing this book, I have made free use of the material furnished by my own recollection, memoranda, and correspondence. I have also consulted many vol- umes by different hands. As I think that most readers are impatient, and with reason, of quotation-marks and foot-notes, I have been sparing of both. By far the lar- gest assistance I have had, has been derived from ad- vance sheets of the Government publication of the Reports of Military Operations During the Eebellion, placed at my disposal by Colonel Robert N. Scott, the officer in charge of the War Records Office of the War Department of the United States, F, W. P. CONTENTS. PAGE List of Maps, ..«.••• « xi CHAPTER I. The Commencement of the Campaign, .... 1 CHAPTER II. South Mountain, 27 CHAPTER III. The Antietam, 43 CHAPTER IV. Fredeeicksburg, 136 APPENDIX A. Commanders in the Army of the Potomac under Major-General George B. -

GAR Posts in PA

Grand Army of the Republic Posts - Historical Summary National GAR Records Program - Historical Summary of Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Posts by State PENNSYLVANIA Prepared by the National Organization SONS OF UNION VETERANS OF THE CIVIL WAR INCORPORATED BY ACT OF CONGRESS No. Alt. Post Name Location County Dept. Post Namesake Meeting Place(s) Organized Last Mentioned Notes Source(s) No. PLEASE NOTE: The GAR Post History section is a work in progress (begun 2013). More data will be added at a future date. 000 (Department) N/A N/A PA Org. 16 January Dis. 1947 Provisional Department organized 22 November 1866. Permanent Beath, 1889; Carnahan, 1893; 1867 Department 16 January 1867 with 19 Posts. The Department National Encampment closed in 1947, and its remaining members were transferred to "at Proceedings, 1948 large" status. 001 GEN George G. Meade Philadelphia Philadelphia PA MG George Gordon Meade (1815- Wetherill House, Sansom Street Chart'd 16 Oct. Originally chartered by National HQ. It was first commanded by Beath, 1889; History of the 1872), famous Civil War leader. above Sixth (1866); Home Labor 1866; Must'd 17 COL McMichael. Its seniority was challenged by other Posts George G. Meade Post No. League Rooms, 114 South Third Oct. 1866 named No. 1 in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. It was found to be One, 1889; Philadelphia in the Street (1866-67); NE cor. Broad the ranking Post in the Department and retained its name as Post Civil War, 1913 and Arch Streets (1867); NE cor. No. 1. It adopted George G. Meade as its namesake on 8 Jan. -

Captain Benjamin F. Lee Collection Regarding 28Th Pennsylvania Infantry and John W

Special Collections and College Archives Finding All Finding Aids Aids 9-2006 MS-079: Captain Benjamin F. Lee Collection regarding 28th Pennsylvania Infantry and John W. Geary Amy Sanderson Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/findingaidsall Part of the Military History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Sanderson, Amy, "MS-079: Captain Benjamin F. Lee Collection regarding 28th Pennsylvania Infantry and John W. Geary." (September 2006). Special Collections and College Archives Finding Aids. Special Collection and College Archives, Musselman Library, Gettysburg College. This finding aid appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/findingaidsall/73 This open access finding aid is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MS-079: Captain Benjamin F. Lee Collection regarding 28th Pennsylvania Infantry and John W. Geary Description The Benjamin F. Lee Collection consists of three series which contain documents relating to requisitions by the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry and correspondence of Lee and John W. Geary between themselves and various other individuals. Special Collections and College Archives Finding Aids are discovery tools used to describe and provide access to our holdings. Finding aids include historical and biographical information about each collection in addition to inventories of their content. More information about our collections can be found on our website http://www.gettysburg.edu/special_collections/collections/. -

The Antietam Manuscript of Ezra Ayres Carman

General Ezra Ayres Carman The Antietam Manuscript of Ezra Ayres Carman "Ezra Ayres Carman was Lt. Colonel of the 7th Regiment of New Jersey Volunteers during the Civil War. He volunteered at Newark, NJ on 3 Sept 1861, and was honorably discharged at Newark on 8 Jul 1862 (This discharge was to accommodate his taking command of another Regiment). Wounded in the line of duty at Williamsburg, Virginia on 5 May 1862 by a gunshot wound to his right arm in action. He also served as Colonel of the 13th Regiment of New Jersey Volunteers from 5 August 1862 to 5 June 1865. He was later promoted to the rank of Brigadier General." "Ezra Ayes Carman was Chief Clerk of the United States Department of Agriculture from 1877 to 1885. He served on the Antietam Battlefield Board from 1894 to 1898 and he is acknowledged as probably the leading authority on that battle . In 1905 he was appointed chairman of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park Commission." "The latest Civil War computer game from Firaxis is Sid Meier's "Antietam". More significant is the inclusion of the previously unpublished manuscript of Ezra Carman, the commanding officer of the 13th New Jersey Volunteers during the battle of Antietam. His 1800-page handwritten account of the battle has sat in the National Archives since it was penned and its release is of interest to people other than gamers." "As an added bonus, the game includes the previously unpublished Civil War manuscript of Ezra Carman, the commanding officer of the 13th New Jersey Volunteers. -

Viewing Our Exhibitions, Or at One of Our Many Engaging and Enlightening Public Programs

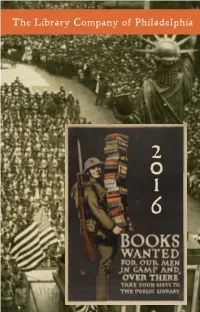

The Library Company of Philadelphia The Annual Report of the Library Company of Philadelphia for the Years 2016 & 2017 Years for the of Philadelphia Company of the Library Report Annual The 2 0 1 6 Philadelphia of Company Library The THE ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARY COMPANY OF PHILADELPHIA FOR THE YEAR 2016 PHILADELPHIA: Te Library Company of Philadelphia 1314 Locust Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107 2019 AR2016.indd 1 10/8/2019 2:42:18 PM President Howell K. Rosenberg Vice President Maude de Schauensee Secretary John F. Meigs Treasurer Charles B. Landreth Trustees Rebecca W. Bushnell Randall M. Miller Harry S. Cherken, Jr. Stephen P. Mullin Nicholas D. Constan, Jr. Daniel K. Richter Maude de Schauensee Howell K. Rosenberg Charles P. Keates, Esq. Richard Wood Snowden Charles B. Landreth Michael F. Suarez, S.J. Michael B. Mann John C. Tuten John F. Meigs Edward M. Waddington Louise Marshall Kelly Clarence Wolf Trustees Emeriti Peter A. Benoliel David W. Maxey Lois G. Brodsky Elizabeth P. McLean Robert J. Christian Martha Hamilton Morris B. Robert DeMento Charles E. Rosenberg Davida T. Deutsch Carol E. Soltis Beatrice W. B. Garvan Seymour I. Toll William H. Helfand Helen S. Weary Roger S. Hillas Michael Zinman Director Richard S. Newman Director Emeritus John C. Van Horne Cover: Marines hold Liberty Sing in front of Liberty Statue in Phila during World War. Books Wanted for our Men (1914-1919). AR2016.indd 2 10/8/2019 2:42:18 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT 4 REPORT OF THE TREASURER 8 REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR 10 EXHIBITIONS -

Inventing the Modern World: TEXT PANELS

Inventing the Modern World: TEXT PANELS Revival and (Re)invention At the 19th-century world’s fairs, many of the manufacturers’ stands were filled with objects laden with historical associations. A fascination with archaeology of the ancient world as well as popular interest in the art and literature of the Middle Ages and pre-Revolutionary France spawned imaginative revival styles, such as Renaissance, Gothic, and Rococo. Each style was imbued with cultural meaning and was often used in America to instill a European legitimacy on the young country’s artistic heritage. Objects in revival styles demonstrated the relevance of motifs and forms from the past on the decorative arts of the present. The succession of revivals also coincided with advancements in machine production, thus uniting the past with modern industry. Decorative arts were now more accessible and affordable, displaying the most current manufacturing methods, and consumers benefited from a greater variety of goods. Avant-garde processes of the time were often displayed through historical patterns and styles, such as Rococo swirls in cast-iron designs by Thomas Jeckyll and Thomas Warren and classically shaped electroplated metals by Elkington & Co. and Ferdinand Barbedienne Foundry. Revivalism became the platform for debuting inventive and progressive technologies that contributed to an increasingly modern world. Historicism: Imitation and Cunning Reproductions Artists who made objects in historicist styles for the world’s fairs sought to obtain the highest level of craftsmanship; many borrowed literally from the past and implemented or re-created ancient techniques. Some objects were so exact in their reproduction that they invited comparisons to originals. -

28Th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-50212 8 Nov 2012

U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center Civil War Unit: 28th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-50212 8 Nov 2012 28th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment Arnold, Peter K. Chattanooga, Savannah and Alexandria: The Diary of one of Sherman’s Soldiers as Recorded by Private Peter K. Arnold (Nornhold), Company B, 28th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Easton, PA: Privately Printed, 1988. 68 p. E601.A76. Association of the 28th and 147th Regiments Infantry and Independent Battery “E,” Light Artillery, Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Association of the.... Philadelphia: Allen, Lane & Scott, 187?. 8 p. E173.P18.no248.pam6. Bates, Samuel P. History of the Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot, 1993. Vol. 1, pp. 418-83. E527.B32.v1. (Brief history and roster of the regiment). "Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel John Page Nicholson, U.S. Volunteers." United Service (1891): pp. 215-16. Per. Brown, H. E. The 28th Regt. P.V.V.I., the 147th Regt. P.V.V.I., and Knap's Ind. Battery “E”, at Gettysburg, July 1, 2, 3, 1863. n.p., n.d. 7 p. E475.53.B76. Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion. Vol. 2. Dayton, OH: Morningside, 1979. p. 1586. E491.D992. (Concise summary of the regiment's service). Fox, Arthur B. Our Honored Dead: Allegheny County, Pennsylvania in the American Civil War. Chicora, PA: Mechling, 2008. pp. 72-76. F157.A4.F69. Hahn, Edward. Company B, 28th Infantry Regiment, Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Greensburg, PA: Westmoreland County Historical Society, 1997. pp. 32-44. E527.5.28th.H33. Hayward, Ambrose H. -

Visitor Center Area Cultural Landscape, Antietam National

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2018 Visitor Center Area Cultural Landscape Antietam National Battlefield (ANTI) December 2018 Antietam Visitor Center Area Cultural Landscape Antietam National Battlefield Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... Page Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan ............................................................................................................... Page Concurrence Status ........................................................................................................................................... Page Geographic Information & Location Map ........................................................................................................ Page Management Information ................................................................................................................................. Page National Register Information .......................................................................................................................... Page Chronology & Physical History ........................................................................................................................ Page Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity ................................................................................................................... Page Condition Assessment ..................................................................................................................................... -

Visitor Center Area Cultural Landscape Antietam National Battlefield (ANTI) December 2018

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2018 Visitor Center Area Cultural Landscape Antietam National Battlefield (ANTI) December 2018 Antietam Visitor Center Area Cultural Landscape Antietam National Battlefield Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... Page Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan ............................................................................................................... Page Concurrence Status ........................................................................................................................................... Page Geographic Information & Location Map ........................................................................................................ Page Management Information ................................................................................................................................. Page National Register Information .......................................................................................................................... Page Chronology & Physical History ........................................................................................................................ Page Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity ................................................................................................................... Page Condition Assessment ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Battle of Wauhatchie

Point Blank Business: the Battle of Wauhatchie Anthony Hodges, May 17, 2021 blueandgrayeducation.org Brown's Tavern, originally associated with the nearby Brown's Ferry, was a private residence at the time of the Brown's Ferry/Wauhatchie operation in 1863. | courtesy of the author A month after the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863, Gen. James Longstreet launched a night attack on a small Union force at Wauhatchie, Tennessee. Here’s how the bloody exchange unfolded. As the sun rose on the morning of October 27, 1863, roughly 4,000 soldiers of the Army of the Cumberland held a lodgment at Brown’s Ferry, west of Chattanooga on the Tennessee River in Lookout Valley. A pontoon bridge, connecting the bridgehead with the main army in Chattanooga, was completed. The Cumberland army had been trapped in Chattanooga since their defeat at Chickamauga in late September, and with the Confederates occupying Lookout and Raccoon mountains, the best available Union supply route was a 60-plus-mile roundabout route that could take a week or more to complete. This arduous route resulted in the death of thousands of mules and horses, further weakening the ability to get supplies to the beleaguered army. As a result, William Rosecrans’s army was reduced to quarter rations and faced starvation by mid-October. Before being relieved of command, Rosecrans tasked the army’s chief engineer, William F. “Baldy” Smith, with developing a plan to open the short route to Bridgeport, or, as the soldiers termed it, Smith was to open the “cracker line.” When Ulysses Grant replaced Rosecrans in late October, he gave Smith the go-ahead to execute the plan, stating that Smith “had been so instrumental in preparing for the move and so clear in his judgment about the manner of making it, that I deemed it but just to him that he should have command of the troops detailed to executed the design.” With the successful nocturnal amphibious assault of October 27 at Brown’s Ferry, the first part of “Baldy” Smith’s plan to open the cracker line had been executed perfectly. -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6668/pennsylvania-county-histories-8656668.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

S-S. V Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun01unse_1 L K L INDEX. Page M Page M Page M N O P Q R R (safety from capture, destruction or disper¬ sion to the patriotic volunteers of the “Old pi Keystone," composed of five independent 'companies and aggregating 530 men. History-the testimony of many eminent (?ivO-cu GV - j men, both living and dead; and the files in the War Department, and the action of the h House of Representatives, in passing unani¬ fciG.. \lrWc . MY|i| mously a resolution of thanks all combine to give the honor to the “First Defenders. No fair minded man, not even the gallant Sixth Massachusetts regiment, will deny this fact. During the visit of the surviv¬ ing members of the Sixth Massachusetts 1 Regiment to this city on their anniversary last vear they received marked honors, at¬ tentions and courtesies from the residents of this city and of Baltimore. All classes in¬ cluding the military, joined ill extending to the remnant of the brave old Sixth tnose Reading’s Title Disputed by Potts- attention?and honors to which they were so justly entitled. PENNSYLVANIA’ S CLAIM ADMITTED. ville and Lewistown. The writer had the pleasure of meeting quite a number of them. All of them freely admitted the fact that the Pennsyl¬ vania troops had proceeded them and were OTHER COMPANIES occupying the House wing of the Capitol when they arrived.