Paradigm Shift: How the Evolution of Two Generations of Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xbox Cheats Guide Ght´ Page 1 10/05/2004 007 Agent Under Fire

Xbox Cheats Guide 007 Agent Under Fire Golden CH-6: Beat level 2 with 50,000 or more points Infinite missiles while in the car: Beat level 3 with 70,000 or more points Get Mp model - poseidon guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 11 Get regenerative armor: Get 130000 points for level 11 Get golden bullets: Get 120000 points for level 10 Get golden armor: Get 110000 points for level 9 Get MP weapon - calypso: Get 100000 points and all 007 medallions for level 8 Get rapid fire: Get 100000 points for level 8 Get MP model - carrier guard: Get 130000 points and all 007 medallions for level 12 Get unlimited ammo for golden gun: Get 130000 points on level 12 Get Mp weapon - Viper: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 6 Get Mp model - Guard: Get 90000 points and all 007 medallions for level 5 Mp modifier - full arsenal: Get 110000 points and all 007 medallions in level 9 Get golden clip: Get 90000 points for level 5 Get MP power up - Gravity boots: Get 70000 points and all 007 medallions for level 4 Get golden accuracy: Get 70000 points for level 4 Get mp model - Alpine Guard: Get 100000 points and all gold medallions for level 7 ghðtï Page 1 10/05/2004 Xbox Cheats Guide Get ( SWEET ) car Lotus Espirit: Get 100000 points for level 7 Get golden grenades: Get 90000 points for level 6 Get Mp model Stealth Bond: Get 70000 points and all gold medallions for level 3 Get Golden Gun mode for (MP): Get 50000 points and all 007 medallions for level 2 Get rocket manor ( MP ): Get 50000 points and all gold 007 medalions on first level Hidden Room: On the level Bad Diplomacy get to the second floor and go right when you get off the lift. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

2475 in 1 Game List

Game List Of Three Sides Cabinet 1 1941 47 Air Gallet (Taiwan) 2 1942 48 Airwolf 3 1943 49 Ajax 4 1944 50 Akkanbeder(ver 2.5j) 5 1945 51 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version N) 6 10 Yard Fight (Japan) 52 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version P) 7 1943kai 53 Ales no Tsubasa (Japan) 8 1945Plus 54 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 9 19xx 55 Alien Syndrome 10 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 56 Alien vs. Predator 11 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 57 Aliens (Japan) 12 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 58 Aliens (US) 13 3D_Beastorizer(US) 59 Aliens (World set 1) 14 3D_Star Gladiator 60 Aliens (World set 2) 15 3D_Star Gladiator 2 61 Alley Master 16 3D_Street Fighter EX(Asia) 62 Alligator Hunt (unprotected) 17 3D_Street Fighter EX(Japan) 63 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian 18 3D_Street Fighter EX(US) 64 Alpha One (prototype, 3 lives) 19 3D_Street Fighter EX2(Japan) 65 Alpine Ski (set 1) 20 3D_Street Fighter EX2PLUS(US) 66 Alpine Ski (set 2) 21 3D_Strider Hiryu 2 67 Altered Beast (Version 1) 22 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 68 Ambush 23 3D_Toshinden 2 69 Ameisenbaer (German) 24 4 En Raya 70 American Speedway (set 1) 25 4-D Warriors 71 Amidar 26 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 72 Amigo 27 800 Fathoms 73 Andro Dunos 28 88 Games! 74 Angel Kids (Japan) 29 '99 The Last War 75 APB-All Points Bulletin 30 A.B. Cop (FD1094 317-0169b) 76 Appoooh 31 Acrobatic Dog_Fight 77 Aqua Jack (World) 32 Act-Fancer (World 1) 78 Aquarium(Japan) 33 Act-Fancer (World 2) 79 Arabian Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon (Japan 34 80 Arabian (Atari) revision 1) 35 Action Fighter 81 Arabian -

Banadive™ AX Interactive Virtual Character Performance System Integrating Game AI and Xr

BANDAI NAMCO Research Inc. NEWS RELEASE № 02-01 June 26, 2020 PRESS RELEASE: BanaDIVE™ AX Interactive Virtual Character Performance System Integrating game AI and xR. The first in the world. ~ First public DJ play performed at “ASOBINOTES” ONLINE FES, a free no spectator online event. ~ BANDAI NAMCO Research Inc. 2-37-25 Eidai, Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan President NAKATANI Hajime In pursuit of our vision of “Creating New Values in Entertainment”, BANDAI NAMCO Research Inc. (hereinafter referred to as “BNR”) has successfully developed the “BanaDIVE™ AX”, an interactive virtual performance system created by integrating game AI (Artificial Intelligence)*1 and xR technology*2. In this system, using pre-analyzed music, the game AI that incorporates DJ performance (seamlessly joining music, controlling the tempo of music, arousing the audience etc.) is linked with the motions of 3D characters and ambience generated in a live music entertainment venue. We also incorporated interactive entertainment elements such as song selection by real-time voting, music linked visual production and AR audio visual direction. As a result, DJ and audiences can, whether at the venue or in remote locations, experience immersive live performances together, In addition to producing live events organized by Bandai Namco Group and conducting experimental collaborations with characters and music creators, BNR will continue to conduct research and development of future entertainment, including collaboration with deep learning-based AI and mechanism to arouse audiences around the world. 1 / 2 BANDAI NAMCO Research Inc. NEWS RELEASE *1 Game AI is a technology based on logicalized behavior of characters and used in many games, such as the monster behavior AI in the video game Pac-Man and COM player behavior control of fighting game "Tekken". -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Sega Master System / Mark III

Sega Master System / Mark III Last Updated on September 30, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Action Fighter Sega After Burner Sega Akai Koudan Zillion Sega Aleste Sega Alex Kidd no Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd: BMX Trial Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Syndrome Sega Anmitsu Hime Sega Argos no Juujiken Salio Ashura Sega Astro Flash Sega Astro Warrior Sega Blade Eagle Sega Bomber Raid Sega Captain Silver Sega Chouon Senshi Borgman Sega Circuit, The Sega Comical Machine Gun Joe Sega Doki Doki Penguin Land: Uchuu Daibouken Sega Double Dragon Sega Double Target: Cynthia no Nemuri Sega Enduro Racer Sega F-16 Fighting Falcon Sega Family Games Sega Fantasy Zone Sega Fantasy Zone II: Opa Opa no Namida Sega Final Bubble Bobble Sega Fushigi no Oshiro Pit Pot Sega Galactic Protector Sega Game de Check! Koutsuu Anzen Tokio Marine and Fire Insur... Ghost House Sega Gokuaku Doumei Dump Matsumoto Sega Great Baseball Sega Great Basketball Sega Great Football Sega Great Golf Sega Great Ice Hockey Sega Great Soccer Sega Great Tennis Sega Great Volleyball Sega Haja no Fuuin Sega Hang-On Sega High School! Kimengumi Sega Hokuto no Ken Sega Hoshi wo Sagasite・・・ Sega Kenseiden Sega Kujaku Ou Sega Lord of Sword Sega Loretta no Shouzou: Sherlock Holmes Sega Mahjong Sengoku Jidai Sega Makai Retsuden Sega Maou Golvellius Sega Masters Golf Sega This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. Sega Master System / Mark III Last Updated on September 30, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Maze Walker Sega Megumi Rescue Sega Nazca '88: The Golden Road to Paradise Sega Nekkyuu Koushien Sega Ninja, The Sega Opa Opa Sega Out Run Sega Phantasy Star Sega Pro Yakyuu Pennant Race, The Sega R-Type Sega Rocky Sega Satellite 7 Sega SDI Sega Seishyun Scandal Sega Shinobi Sega Solomon no Kagi: Oujo Rihita no Namida Salio Space Harrier Sega Space Harrier 3-D Sega Sports Pad Soccer Sega Spy vs. -

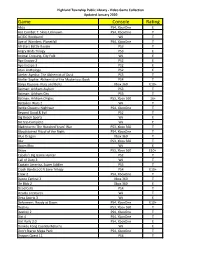

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

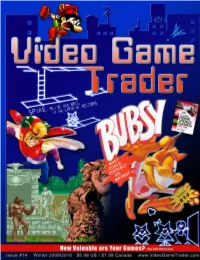

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Full Games List Pandora DX 3000 in 1

www.myarcade.com.au Ph 0412227168 Full Games List Pandora DX 3000 in 1 1. 10-YARD FIGHT – (1/2P) – (1464) 38. ACTION 52 – (1/2P) – (2414) 2. 16 ZHANG MA JIANG – (1/2P) – 39. ACTION FIGHTER – (1/2P) – (1093) (2391) 40. ACTION HOLLYWOOOD – (1/2P) – 3. 1941 : COUNTER ATTACK – (1/2P) – (362) (860) 41. ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES – (1/2P) – 4. 1942 – (1/2P) – (861) (2431) 5. 1942 – AIR BATTLE – (1/2P) – (1140) 42. ADVENTUROUS BOY-MAO XIAN 6. 1943 : THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – XIAO ZI – (1/2P) – (2266) (1/2P) – (862) 43. AERO FIGHTERS – (1/2P) – (927) 7. 1943 KAI : MIDWAY KAISEN – (1/2P) 44. AERO FIGHTERS 2 – (1/2P) – (810) – (863) 45. AERO FIGHTERS 3 – (1/2P) – (811) 8. 1943: THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY – 46. AERO FIGHTERS 3 BOSS – (1/2P) – (1/2P) – (1141) (812) 9. 1944 : THE LOOP MASTER – (1/2P) 47. AERO FIGHTERS- UNLIMITED LIFE – (780) – (1/2P) – (2685) 10. 1945KIII – (1/2P) – (856) 48. AERO THE ACRO-BAT – (1/2P) – 11. 19XX : THE WAR AGAINST DESTINY (2222) – (1/2P) – (864) 49. AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 – (1/2P) – 12. 2 ON 2 OPEN ICE CHALLENGE – (2624) (1/2P) – (1415) 50. AERO THE ACRO-BAT 2 (USA) – 13. 2020 SUPER BASEBALL – (1/2P) – (1/2P) – (2221) (1215) 51. AFTER BURNER II – (1/2P) – (1142) 14. 3 COUNT BOUT – (1/2P) – (1312) 52. AGENT SUPER BOND – (1/2P) – 15. 4 EN RAYA – (1/2P) – (1612) (2022) 16. 4 FUN IN 1 – (1/2P) – (965) 53. AGGRESSORS OF DARK KOMBAT – 17. 46 OKUNEN MONOGATARI – (1/2P) (1/2P) – (106) – (2711) 54.