The Essential MILTON FRIEDMAN FRIEDMAN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9.1 Financial Cost Compared with Economic Cost 9.2 How

9.0 MEASUREMENT OF COSTS IN CONSERVATION 9.1 Financial Cost Compared with Economic Cost{l} Since financial analysis relates primarily to enterprises operating in the market place, the data of costs and retums are derived from the market prices ( current or expected) of the transactions as they are experienced. Thus the cost of land, capital, construction, etc. is the ~ recorded price of the accountant. By contrast, in economic analysis ( such as cost bene fit analysis) the costs and benefits of a project are analysed from the point of view of society and not from the point of view of a single agent's utility of the landowner or developer. They are termed economic. Some effects of the project, though conceming the single agent, do not affect society. Interest on borrowing, taxes, direct or indirect subsidies are transfers that do not deploy real resources and do not therefore constitute an economic cost. The costs and the retums are, in part at least, based on shadow prices, which reflect their "social value". Economic rate of retum could therefore differ from the financial costs which are based on the concept of "opportunity cost"; they are measured not in relation to the transaction itself but to the value of the resources which that financial cost could command, just as benefits are valued by the resource costs required to achieve them. This differentiation leads to the following significant rules in conside ring costs in cost benefit analysis, as for example: (a) Interest on money invested This is a transfer cost between borrower and lender so that the economyas a whole is no different as a result. -

Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Economics of Investment in Human Resources

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 04E d48 VT 012 352 AUTHOR Wood, W. D.; Campbell, H. F. TITLE Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Economics of Investment in Human Resources. An Annotated Bibliography. INSTITUTION Queen's Univ., Kingston (Ontario). Industrial Felaticns Centre. REPORT NO Eibliog-Ser-NO-E PU2 EATS 70 NOTE 217F, AVAILABLE FROM Industrial Relations Centre, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada ($10.00) EDBS PRICE EDPS Price MF-$1.00 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, *Cost Effectiveness, *Economic Research, *Human Resources, Investment, Literature Reviews, Resource Materials, Theories, Vocational Education ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography presents 389 citations of periodical articles, monographs, and books and represents a survey of the literature as related to the theory and application of cost-benefit analysis. Listings are arranged alphabetically in these eight sections: (1) Human Capital, (2) Theory and Application of Cost-Benefit Analysis, (3) Theoretical Problems in Measuring Benefits and Costs,(4) Investment Criteria and the Social Discount Rate, (5) Schooling,(6) Training, Retraining and Mobility, (7) Health, and (P) Poverty and Social Welfare. Individual entries include author, title, source information, "hea"ings" of the various sections of the document which provide a brief indication of content, and an annotation. This bibliography has been designed to serve as an analytical reference for both the academic scholar and the policy-maker in this area. (Author /JS) 00 oo °o COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS AND THE ECONOMICS OF INVESTMENT IN HUMAN RESOURCES An Annotated Bibliography by W. D. WOOD H. F. CAMPBELL INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS CENTRE QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY Bibliography Series No. 5 Cost-Benefit Analysis and the Economics of investment in Human Resources U.S. -

Lost Wages: the COVID-19 Cost of School Closures

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13641 Lost Wages: The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures George Psacharopoulos Victoria Collis Harry Anthony Patrinos Emiliana Vegas AUGUST 2020 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 13641 Lost Wages: The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures George Psacharopoulos Harry Anthony Patrinos Georgetown University The World Bank and IZA Victoria Collis Emiliana Vegas The EdTech Hub Center for Universal Education, Brookings AUGUST 2020 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany Email: [email protected] www.iza.org IZA DP No. 13641 AUGUST 2020 ABSTRACT Lost Wages: The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures1 Social distancing requirements associated with COVID-19 have led to school closures. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Robert Fogel Interview

RF Winter 07v43-sig3-INT 2/28/07 11:13 AM Page 44 INTERVIEW Robert Fogel In the early 1960s, few economic historians engaged RF: I understand that your initial academic interests in rigorous quantitative work. Robert Fogel and the were in the physical sciences. How did you become “Cliometric Revolution” he led changed that. Fogel interested in economics, especially economic history? began to use large and often unique datasets to test Fogel: I became interested in the physical sciences while some long-held conclusions — work that produced attending Stuyvesant High School, which was exceptional in some surprising and controversial results. For that area. I learned a lot of physics, a lot of chemistry. I had instance, it was long believed that the railroads had excellent courses in calculus. So that opened the world of fundamentally changed the American economy. science to me. I was most interested in physical chemistry and thought I would major in that in college, but my father said Fogel asked what the economy would have looked that it wasn’t very practical and persuaded me to go into like in their absence and argued that, while important, electrical engineering. I found a lot of those classes boring the effect of rail service had been greatly overstated. because they covered material I already had in high school, so it wasn’t very interesting and my attention started to drift elsewhere. In 1945 and 1946, there was a lot of talk about Fogel then turned to one of the biggest issues in all whether we were re-entering the Great Depression and the of American history — antebellum slavery. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Forms of Government

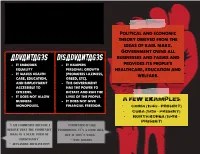

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

Gary Becker and the Art of Economics by Aloysius Siow, Professor of Economics, University of Toronto May 24, 2014

Gary Becker and the Art of Economics by Aloysius Siow, Professor of Economics, University of Toronto May 24, 2014. Gary Becker, an American economist, died on May 3, 2014, at the age of 83. His major contribution was the systematic application of economics to the analysis of social issues. He used economics to study discrimination, criminal behavior, human capital, marriage, fertility and other social issues. Becker won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1992. He also won the John Bates Clark medal, awarded to the best American economist under 40, in 1967; and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor award by the US president to a civilian, in 2007. Becker's father, Louis William Becker, migrated from Montreal to the United States at age sixteen and moved several times before settling down in Pottsville, Pennsylvania. Becker's mother was Anna Siskind. He was born in Pottsville in 1930. At age five, Gary and his family moved to Brooklyn. He graduated from James Madison High School and went to Princeton University for college. He did his PhD at the University of Chicago where he met Milton Friedman who would have an enormous influence on his intellectual development. After he obtained his PhD, Becker spent a few years as an assistant professor at the University of Chicago and then moved to Columbia University. In 1970, Becker returned to the University of Chicago where he remained as a professor until his death. While impressive, a list of what he wrote on does not explain why he is so intellectually influential. His mentor, Friedman, always said that "There is no such thing as a free lunch" and applied it widely in market environments. -

Some Political Economy of Monetary Rules

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Some Political Economy of Monetary Rules F ALEXANDER WILLIAM SALTER n this paper, I evaluate the efficacy of various rules for monetary policy from the perspective of political economy. I present several rules that are popular in I current debates over monetary policy as well as some that are more radical and hence less frequently discussed. I also discuss whether a given rule may have helped to contain the negative effects of the recent financial crisis. -

Education Policy and Friedmanomics: Free Market Ideology and Its Impact

Education Policy and Friedmanomics: Free Market Ideology and Its Impact on School Reform Thomas J. Fiala Department of Teacher Education Arkansas State University Deborah Duncan Owens Department of Teacher Education Arkansas State University April 23, 2010 Paper presented at the 68th Annual National Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association Chicago, Illinois 2 ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to examine the impact of neoliberal ideology, and in particular, the economic and social theories of Milton Friedman on education policy. The paper takes a critical theoretical approach in that ultimately the paper is an ideological critique of conservative thought and action that impacts twenty-first century education reform. Using primary and secondary documents, the paper takes an historical approach to begin understanding how Friedman’s free market ideas helped bring together disparate conservative groups, and how these groups became united in influencing contemporary education reform. The paper thus considers the extent to which free market theory becomes the essence of contemporary education policy. The result of this critical and historical anaysis gives needed additional insights into the complex ideological underpinnings of education policy in America. The conclusion of this paper brings into question the efficacy and appropriateness of free market theory to guide education policy and the use of vouchers and choice, and by extension testing and merit-based pay, as free market panaceas to solving the challenges schools face in the United States. Administrators, teachers, education policy makers, and those citizens concerned about education in the U.S. need to be cautious in adhering to the idea that the unfettered free market can or should drive education reform in the United States. -

Capabilities, Human Flourishing and the Health Gap Amartya Sen

Capabilities, Human Flourishing and the Health Gap Amartya Sen Lecture HDCA Conference Tokyo 2016 Amartya Sen’s insights have been important to my work in at least four ways: providing intellectual justification for my empirical findings that health can be an “outcome” of social and economic processes; providing insight into the debate on relative or absolute inequality; emphasising the central place of freedoms or agency in human well-being; and alerting me to the importance of the question of “inequality of what”. This last is shameful to admit for someone, me, who had been pursuing research on inequalities in health for two decades before I met Sen in person and in his writings. Could I really be obsessed with health inequalities without recognising that there was more than one way to think about inequality? In this Amartya Sen lecture, I will start by sketching briefly how these seminal ideas of Sen influence what I do. More accurately, I should say how Sen’s ideas influence how I think about what I do. For, as just stated, I had been doing it for some time before I encountered Sen’s fundamental contributions – I am a doctor and medical scientist, after all. In particular, my research on health inequalities has focussed on the social gradient in health, its generalisability, how to understand its causes and what to do about it. I have pursued this research since 1976 when I began work on the first Whitehall study(1), and to think about health inequalities more generally (2). Although I had not used the term, “social determinants of health” until later(3), my research on health inequalities fitted that description, along with the research on health of migrants.(4, 5) I will then illustrate the approach in more detail, drawing on my book, The Health Gap. -

Anticipation of Future Consumption: a Monetary Perspective

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Faria, Joao Ricardo; McAdam, Peter Working Paper Anticipation of future consumption: a monetary perspective ECB Working Paper, No. 1448 Provided in Cooperation with: European Central Bank (ECB) Suggested Citation: Faria, Joao Ricardo; McAdam, Peter (2012) : Anticipation of future consumption: a monetary perspective, ECB Working Paper, No. 1448, European Central Bank (ECB), Frankfurt a. M. This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/153881 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu WORKING PAPER SERIES NO 1448 / JULY 2012 ANTICIPATION OF FUTURE CONSUMPTION A MONETARY PERSPECTIVE by Joao Ricardo Faria and Peter McAdam In 2012 all ECB publications feature a motif taken from the €50 banknote.