Valerie's Thesis Aug28revisions2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story

USA TODAY Life Section D Tuesday, November 22, 2005 Cover Story: http://www.usatoday.com/life/people/2005-11-21-huffman_x.htm Felicity Huffman is sitting pretty: Emmy-winning Housewives star ignites Oscar talk for transsexual role By William Keck, USA TODAY By Dan MacMedan, USA TODAY Has it all: An actress for more than twenty years, Felicity Huffman has an Emmy for her role on hit Desperate Housewives, a critically lauded role in the film Transamerica, a famous husband (William H. Macy) and two daughters. 2 WEST HOLLYWOOD Felicity Huffman is on a wild ride. Her ABC show, Desperate Housewives, became hot, hot, hot last season and hasn't lost much steam. She won the Emmy in September over two of her Housewives co-stars. And now she is getting not just critical praise, but also Oscar talk, for her performance in the upcoming film Transamerica, in which she plays Sabrina "Bree" Osbourne, a pre- operative man-to-woman transsexual. After more than 20 years as an actress, this happily married, 42-year-old mother of two is today's "it" girl. "It couldn't happen to a nicer gal," says Housewives creator Marc Cherry. "Felicity is one of those success stories that was waiting to happen." Huffman has enjoyed the kindness of critics before, particularly for her role on Sports Night, an ABC sitcom in the late '90s. And Cherry points out that her stock in Hollywood has been high. "She has always had the respect of this entire industry," he says. But that's nothing like having a hit show and a movie with awards potential, albeit a modestly budgeted, art house-style film. -

Transgender Representation on American Narrative Television from 2004-2014

TRANSJACKING TELEVISION: TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION ON AMERICAN NARRATIVE TELEVISION FROM 2004-2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Kelly K. Ryan May 2021 Examining Committee Members: Jan Fernback, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Ron Becker, External Member, Miami University ABSTRACT This study considers the case of representation of transgender people and issues on American fictional television from 2004 to 2014, a period which represents a steady surge in transgender television characters relative to what came before, and prefigures a more recent burgeoning of transgender characters since 2014. The study thus positions the period of analysis as an historical period in the changing representation of transgender characters. A discourse analysis is employed that not only assesses the way that transgender characters have been represented, but contextualizes American fictional television depictions of transgender people within the broader sociopolitical landscape in which those depictions have emerged and which they likely inform. Television representations and the social milieu in which they are situated are considered as parallel, mutually informing discourses, including the ways in which those representations have been engaged discursively through reviews, news coverage and, in some cases, blogs. ii To Desmond, Oonagh and Eamonn For everything. And to my mother, Elaine Keisling, Who would have read the whole thing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the research and writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance, and therefore offer many thanks. To my Dissertation Chair, Jan Fernback, whose feedback on my writing and continued support and encouragement were invaluable to the completion of this project. -

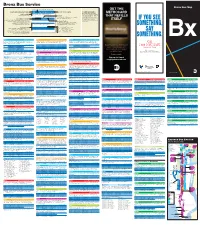

Bronx Bus Map October 2018

Bronx Bus Service Color of band matches color of route on front of map. Borough Abbreviation & Route Number Bx6 East 161st/East 163rd Streets Major Street(s) of Operation For Additional Information More detailed service information, Route Description Daytime and evening service operates between Hunts Point Food Distributon Center, and Riverside Dr West (Manhattan), daily. timetables and schedules are available Daily means 7 days a week. Terminals on the web at mta.info. Or call 511 and AVG. FREQUENCY (MINS.) say Subways and Buses”. Timetables TOWARD HUNTS PT TOWARD RIVERSIDE DR W AM NOON PM EVE NITE Toward Riverside Dr W means the bus originates at the opposite terminal, Hunts Pt. and schedules are also displayed at most Days & Hours of Operation WEEKDAYS: 5:14AM – 1:10AM 4:32AM – 12:30AM 6 10 8 8 – SATURDAYS: 6:00AM –1:00AM 5:16AM – 12:20AM 12 12 12 10 – bus stops. Note: traffic and other As shown, the first bus of the Weekdays Morning Rush Service, SUNDAYS: 5:52AM –1:10AM 5:29AM – 12:30AM 15 12 12 11 – conditions can affect scheduled arrivals IF YOU SEE (traveling toward Hunts Point Food Distribution Center) Frequency of Service and departures. leaves Riverside Drive West at 5:14 am. The approximate time between buses, in minutes. The last bus of the Weekdays Evening Service Late night service operates between Hunts Point Food Distribution In this case, Buses should arrive every 6 minutes leaves Riverside Drive West at 1:10 am. Center and West 155 St/Amsterdam Av (Manhattan), daily. during the Weekdays Morning Rush Service. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Bronx Bodega Partners Workgroup Don't Stress, Eat Fresh Marketing Campaign 1 the Don't Stress, Eat Fresh Bronx Bodegas Marke

Bronx Bodega Partners Workgroup Don’t Stress, Eat Fresh Marketing Campaign The Don’t Stress, Eat Fresh Bronx bodegas marketing campaign, created by the Bronx Bodega Partners Workgroup (BBW), was officially launched November 15, 2017 to encourage Bronx residents to purchase healthier foods and beverages at bodegas in the Bronx. With Bronx bodegas selling healthier options -- fresh fruits and vegetables, healthy sandwiches, low-fat dairy products, water and low sodium products -- thousands of Bronx residents now have greater access to healthy foods in their neighborhood bodegas, an important means of improving their health. Begun in 2016, the workgroup includes: the Institute for Family Health's Bronx Health REACH Coalition, Montefiore's Office of Community & Population Health, BronxWorks, Bronx Community Health Network, the Bodega Association of the United States, the Hispanic Information and Telecommunications Network, Inc., the American Dairy Association North East, WellCare Health Plans Inc, Urban Health Plan, City Harvest, the NYC Department of Health – Bronx Neighborhood Health Action Center, and BronxCare Health System. The Bronx Bodega Partners Workgroup together works with 53 stores. The marketing campaign was created by MESH Design and Development, a small design firm selected by the workgroup. The campaign design was informed by community focus groups that included youth from the Mary Mitchell Family and Youth Center and from the South Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation both youths and adults. Participants provided ideas for content, color, and images. The campaign ran from October 2018 through January 2019 with signage in English and Spanish. The bodegas received posters, shelf signs and door clings. Posters were also distributed to neighboring businesses located near the bodegas. -

CNTV 457 Fall 2021 Syllabus.Docx

CNTV 457 The Entertainment Entrepreneur: Getting your First Project Made Units: 2 Term: Fall 2021 Day—Time: Tuesdays, 7-10pm Location: SCA 110 Professors Sam Canter CEO/Partner, Psycho Films E-mail: [email protected] Office: (303)956-0609 Christian Sutton Partner/Director, Psycho Films E-mail: [email protected] Course Description This course will cover the practical aspects of why it is essential to be entrepreneurial within the changing landscape of the entertainment industry. Whether you strive to be a content creator, producer, writer, director, executive, or form your own business/creative venture, this course will help you identify how and why you should be creating your own projects. The content of this course will cover the benefits and pitfalls of developing your own content, companies, and/or partnerships. We will also explore the practical and real obstacles and opportunities you face as you leave USC SCA and begin to work in the entertainment industry. Where should I work? How do I make my projects? How do I start my own company or brand? In addition, key aspects of the producing process from both a creative and business executive side will be covered in the Film, TV, VR, and digital media spaces. The class will be broken down into 3 sections, “The Creative Process,” “Development and Production,” and “Marketing and Selling your Project.” Each class will feature panels or select speakers of industry professionals. Including top talent, producers, directors, studio executives, heads of production companies, lawyers, agents, managers, etc. In addition to seasoned veterans of the entertainment industry, this course will also include a series of guest speakers, all who began forging their own path in the industry during or immediately after college. -

Montefiore Rn Network Provider Directory

MONTEFIORE RN NETWORK PROVIDER DIRECTORY June 2019 CMO, Montefiore Care Management 200 Corporate Boulevard South Yonkers, NY 10701 Table of Contents Specialty Page Number Acupuncture 66 Addiction Medicine 66 Addiction Psychiatry 66 Adolescent & Adult Psychiatry 66 Adolescent & Adult Psychotherapy 66 Adolescent Medicine 1, 66 Adult & Child Psychiatry 67 Adult Psychiatry 67 Adult Psychotherapy 69 Advanced HF/Transplant Cardiology 70 Allergy & Immunology 71 Anatomic & Clinical Pathology 73 Anatomic Pathology 80 Anesthesiology 82 Audiology 96 Blood Banking/Transfusion Medicine 98 Brain Injury Medicine 99 Cardiovascular Disease 100 Certified Nurse Anesthetist 112 Certified Nurse Midwife 119 Child & Adolescent & Adult Psychiatry 119 Child & Adolescent & Adult Psychotherapy 119 Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 119 Child & Adolescent Psychology 121 Child & Adolescent Psychotherapy 121 Child Abuse Pediatrics 121 Child Neurology 121 Clinical Biochemical Genetics 122 Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology 123 Clinical Cytogenetics 124 Clinical Genetics 124 Clinical Molecular Genetics 125 Clinical Neurophysiology 125 Clinical Nurse Specialist Core 126 Clinical Pathology 126 Colon & Rectal Surgery 127 Critical Care Medicine 128 Cytopathology 132 Dermatology 133 Dermatopathology 136 Developmental Pediatrics 137 Diagnostic Radiology 137 Dietetic - Nutrition 182 Emergency Medicine 183 Endocrinology, Diabetes, & Met 190 Specialty Page Number Epilepsy 193 Family Medicine 1, 195 Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery 195 Forensic Psychiatry 195 Gastroenterology -

Understanding the Market for Gender Confirmation Surgery in the Adult Transgender Community in the United States

Understanding the Market for Gender Confirmation Surgery in the Adult Transgender Community in the United States: Evolution of Treatment, Market Potential, and Unique Patient Characteristics The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Berhanu, Aaron Elias. 2016. Understanding the Market for Gender Confirmation Surgery in the Adult Transgender Community in the United States: Evolution of Treatment, Market Potential, and Unique Patient Characteristics. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Medical School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40620231 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Scholarly Report submitted in partial fulfillment of the MD Degree at Harvard Medical School Date: 1 March 2016 Student Name: Aaron Elias Berhanu, B.S. Scholarly Report Title: UNDERSTANDING THE MARKET FOR GENDER CONFIRMATION SURGERY IN THE ADULT TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY IN THE UNITED STATES: EVOLUTION OF TREATMENT, MARKET POTENTIAL, AND UNIQUE PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS Mentor Name and Affiliation: Richard Bartlett MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School, Children’s Hospital of Boston Collaborators and Affiliations: None ! TITLE: Understanding the market for gender confirmation surgery in the adult transgender community in the United States: Evolution of treatment, market potential, and unique patient characteristics Aaron E Berhanu, Richard Bartlett Purpose: Estimate the size of the market for gender confirmation surgery and identify regions of the United States where the transgender population is underserved by surgical providers. -

Enterprise WORDPRESS+FOR+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++RISE

WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+ENTERPRISE++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+ENTERPRIS+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+ENTERPRI++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+ENTERPR+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+ENTERP++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+ENTE++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+ENT+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE+E+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ WORDPRESS+FOR+THE++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++E WORDPRESS+FOR+TH++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++SE WORDPRESS+FOR+T++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ISEEnterprise WORDPRESS+FOR+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++RISE WORDPRESS+FO+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++PRISE WORDPRESS+F+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++RPRISEWordPress WORDPRESS++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ERPRISE WORDPRES++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++TERPRISE WORDPRE+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++NTERPRISE10 CASE STUDIES WORDPR+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ENTERPRISEOF WORDPRESS AT SCALE WORDP++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++E+ENTERPRISE WORD+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++HE+ENTERPRISE WOR+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++THE+ENTERPRISE WO++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++R+THE+ENTERPRISE -

Live Nation Revenue Wiped out by COVID; CEO Michael Rapino Sees Live Events in Full Swing Next Summer by Jill Goldsmith August 5, 2020 5:05Pm

6/8/2020 Live Nation Revenue Wiped Out By COVID – Deadline TIP US HOME / BUSINESS / BREAKING NEWS Live Nation Revenue Wiped Out By COVID; CEO Michael Rapino Sees Live Events In Full Swing Next Summer By Jill Goldsmith August 5, 2020 5:05pm Courtesy Paramount Pictures https://deadline.com/2020/08/live-nation-revenue-wiped-out-by-covid-ceo-michael-rapino-sees-live-events-in-full-swing-next-summer-1203005595/ 1/10 6/8/2020 Live Nation Revenue Wiped Out By COVID – Deadline Let’s get this over with. Live Nation, which makes a living on live events, saw revenue plunge 98% last TIP US quarter to $74 million and swung to a loss of $588 million from a profit of $176 million the year before. It was the first full COVID-19 quarter and the company was expected to bleed red ink. CEO Michael Rapino can only look ahead. And he did as the company reported financial results for the three months ended in June. He said he expects live events to “return at scale in the summer of 2021,” with ticket sales ramping up in the quarters leading up to summer shows. He noted that 86% of fans opted to keep tickets for rescheduled shows and that two-thirds of fans are keeping tickets for canceled festivals so they can go to next year’s show. The company cited strong early ticket sales for festivals in the U.K. next summer, for example, with Download and Isle of Wight pacing well ahead of last year. ADVERTISEMENT RELATED STORY AMC Entertainment Q2 Revenues Plunge, Swings To The Red In "Most Challenging Quarter In 100-Year History" - CEO Adam Aron Between tickets held by fans for rescheduled shows and festival sales, the company, which owns Ticketmaster, said it’s already sold 19 million tickets to more than four thousand concerts and festivals scheduled for 2021, “creating a strong baseload of demand that is pacing well ahead of this point last year.” Can Live Nation last that long? Rapino says yes. -

Community District Profiles

BRONX COMMUNITY DISTRICT 12 8 12 TOTAL POPULATION 1980 1990 2000 7 10 11 Number 128,226 129,620 149,077 12 5 6 10 10 4 3 % Change - 1.1 15.0 10 9 9 10 1 2 11 11 1 VITAL STATISTICS 1990 2000 7 8 7 1 11 11 4 3 Births: Number 2,223 1,895 5 Rate per 1000 17.2 12.7 CITY CITY LINE Deaths: Number 1,353 983 T LINE ND A T TL S R EA Rate per 1000 10.4 6.6 O K C R N A A P WOODLAWN V WAKEFIELD . E ED Infant Mortality: Number 37 15 V EN A W A E SETON L Rate per 1000 16.6 7.9 M FALLS D ER N T E O PARK S W E E R H N PARK DRIVE E WOODLAWNCEMETERY C G WILLIAMSBRIDGE T L J E. 211th S A ST. A N E D . T .R BAYCHESTER H R .Y. R N U .- OLINVILLE H W . N N EAST GUN HILL ROADA Y ADEE AVE. STO O . B INCOME SUPPORT 1994 2001 RD Public Assistance 19,017 9,435 (AFDC, Home Relief) LAND USE, 2001 Supplemental Security 4,937 5,974 Income Lot Area Lots Sq. Ft.(000) % Medicaid Only 5,828 11,128 1- 2 Family Residential 14,039 39,954.6 38.7 Multi-Family Residential 2,954 16,617.6 16.1 Total Persons Assisted 29,782 26,537 Mixed Resid. / Commercial 426 1,633.9 1.6 Commercial / Office 417 4,045.8 3.9 Percent of Population 23.0 17.8 Industrial 147 3,588.8 3.5 Transportation / Utility 162 2,760.9 2.7 Institutions 206 6,316.2 6.1 Open Space / Recreation 18 19,858.1 19.2 Parking Facilities 414 2,011.7 2.0 TOTAL LAND AREA Vacant Land 1,152 6,290.3 6.1 Miscellaneous - 266.5 .3 Acres: 3,596.3 Square Miles: 5.6 Total 19,935 103,344.4 100.0 , New York City Department of City Planning (Dec. -

Representing Trans Road Narratives in Mainstream Cinema (1970-2016)

Wish You Were Here: Representing Trans Road Narratives in Mainstream Cinema (1970-2016) by Evelyn Deshane A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Evelyn Deshane 2019 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Dr. Dan Irving Associate Professor Supervisor Dr. Andrew McMurry Associate Professor Internal-external Member Dr. Kim Nguyen Assistant Professor Internal Members Dr. Gordon Slethaug Adjunct Professor Dr. Victoria Lamont Associate Professor ii Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract When Christine Jorgensen stepped off a plane in New York City from Denmark in 1952, she became one of the first instances of trans celebrity, and her intensely popular story was adapted from an article to a memoir and then a film in 1970. Though not the first trans person recorded in history, Jorgensen's story is crucial in the history of trans representation because her journey embodies the archetypal trans narrative which moves through stages of confusion, discovery, cohesion, and homecoming. This structure was solidified in memoirs of the 1950- 1970s, and grew in popularity alongside the booming film industry in the wake of the Hays Production Code, which finally allowed directors, producers, and writers to depict trans and gender nonconforming characters and their stories on-screen.