Portraits and Mug Shots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Collection Includes a Medal Bearing the Portrait of the Dashing Edward VIII, As Well As Two Colonial Coins from British West Africa

This collection includes a medal bearing the portrait of the dashing Edward VIII, as well as two colonial coins from British West Africa. The West Africa coins do not show his portrait because he abdicated too soon for the dies to be used in striking. On 20 January, 1936, Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, of the House of Windsor, succeeded his father, George V, as King of Great Britain and the Dominions of the British Empire. Edward VIII would abdicate in December of the same year, in order to marry the love of his life, the twice-divorced American arriviste Wallis Simpson. His 326-day reign is among the shortest in the long annals of British history. When he was Prince of Wales, Edward became arguably the world’s first modern international celebrity. Exploits of the royal family have always been the subject of great popular interest, but Edward took to the role like none of his predecessors ever had. He was handsome, suave, fashionable, and unlike his stolid and old-fashioned father, he seemed to emulate the ebullient spirit of the post-war Jazz Age. In short, he had it all. That he would surrender so precious a prize as the British throne to marry a commoner—an American commoner, at that, and one with a somewhat notorious past—was widely viewed as the ultimate romantic gesture: a declaration of love ne plus ultra. In fact, there is more to this tale than meets the eye. Abdication was not a great sacrifice for Edward VIII. As much as he loathed “princing,” as he called it, when he’d been Prince of Wales, he hated being king even more. -

Mediacide: the Press's Role in the Abdication Crisis of Edward VIII

___________________________________________________________ Mediacide: the Press’s Role in the Abdication Crisis of Edward VIII Joel Grissom ___________________________________________________________ On December 10, 1936, a group of men entered the ornate drawing room of Fort Belvedere, the private get-away of His Majesty, King Edward VIII. The mood of the room was informal as the King sat at his desk. Fifteen documents lay before him ready for his signature. Briefly scanning them, he quickly affixed, Edward, RI, to the documents. He then relinquished his chair to his brother, Albert, Duke of York, who did the same. The process was repeated twice more as Henry, Duke of Gloucester, and George, Duke of Kent, also signed the documents. The King stepped outside and inhaled the fresh morning air.1 To the King it smelled of freedom. After months of battling with his Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, and the Prime Minister’s allies in the establishment and the press, Edward was laying down the crown in order to marry the woman he loved, an American divorcee named Wallis Simpson. The next day the newspaper headlines across the world would broadcast the news of the King’s unprecedented decision. With the signing of the Instrument of Abdication, Edward had signed away his throne. The newspapers in both the United States and the United Kingdom that would report the abdication had played a major role in bringing about the fall of the King. While the British media had observed a blackout during most of the crisis, the media in the United States had reported the story of the King and Mrs. -

CABINET WINS in BITTER' Ncht Wmr Monarch

-'ir’. ' f, I ■Sr-f’. .... l b Wm a« 0 .‘ Store Open Plenty of PVae ^ rld n f Space. -".V, f A.BLtoSP.M. ■ ;j'- - hi tohlgh* 5> Thnnday npil Saturday Santa In Toyland 9-to S P. IL , change hi < 9 A. M. to 9 P. M. and Than, a ^ Sat. 7 to 9 P. M. MANCHESTER— A CITY OP VILLAGE CHARM VOL.LVL.n o . 60 I AflyitiWag a« Page 10.) MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, DECEMBER 10,1986. <TWBLVE PAGES) PRICE THREE Lounging Pajamas GIVE A DRESS Hera li the answer, to "What For Chriatmas! shall I itveT” These twtMiiece pajamas la plain crepe and printed No more welcome glTt could be satin, buttoned high at the neck selected than one of these good looking dresses' in the Igtest styles and materials. We have a large •nuut. $ 4.50 selection for you to choose from. 8iaesl4to44. $3.98—$10.98 iSt< • •' RULE AS GEORGE VI POPE SUFFERS Steps Doum From Throne MRS. SIMPSON ANEW SEIZURE PLANS TO STAY CABINET WINS IN BITTER' iSKI OF P m Y S I S PANTS IN Sjq,USI0N These come in ^ SLIPS brown, wine, navy, ^ Has Relapse Hiis Morning and green. Sixes 8 Her New York Friend TeDs ncHT w m r m o n a r c h to 20. f $1.98—$2.98 Silk and Satin SKI and Vatican Fears He Wil $2.98 Reporters Edward WiD Lace Trimmed Nerer Walk Again; Stim- GOWNS SUITS Not Join Her at the Villa G reat Britain ^s N ew K in g T A m Gaing To M arry SWEATERS Everyone who loves 1 ^ , $2.98-^$3.98 UNDERWEAR sports wants one of inFrimce. -

PHOTOGRAPHING the CITY the Major Themes Include Transportation, Commerce, Disaster, Wallis Simpson, Was Photographing the City and Community

January, February, March 2013 PHOTOGRAPHING THE CITY The major themes include transportation, commerce, disaster, Wallis Simpson, was Photographing the City and community. Roads, rail, bridges, and waterways are only 33 at the time Bogies & Stogies Opening February 9 essential to urban life, for example, moving both people and and loved to golf. He Director’s Welcome goods, as indicated by the photograph by Clark Blickensderfer, dressed as a golfer, Golf Tournament Dear Friends: This exhibition explores how nineteenth and twentieth-century reproduced on the cover. This is not an east coast metropolis, or not as a prince, for his Renaissance Vinoy Resort and photographers responded to cities and towns, presented and even Chicago or Kansas City, but Denver. portrait. Sir Henry Golf Club With the joyous holiday season upon preserved their history, and influenced their perception by the Raeburn’s portraits November 5 us, the front of the Museum of Fine public. Among the artists represented are Berenice Abbott, The image by an unknown documentary photographer or in the exhibition will Arts is illuminated with seasonal Walker Evans, Aaron Siskind, Weegee, and Garry Winogrand. photojournalist of a Boston nightclub fire is one of dozens bring to mind his The Museum thanks the lighting, made possible by the capturing this horrific event in which hundreds lost their lives. impressive painting in following for making this benefit generosity of the Frank E. Duckwall Several images are part of the exhibition. Photographs once the MFA collection, on such a success: Foundation. Inside, our magnificent collection joins again contributed to societal change. Numerous codes to protect view in The Focardi exciting exhibitions in welcoming members and visitors. -

Queen Elizabeth II the Queen’S Early Life the Queen Was Born at 2.40Am on 21 April 1926 at 17 Bruton Street in Mayfair, London

Queen Elizabeth II The Queen’s early life The Queen was born at 2.40am on 21 April 1926 at 17 Bruton Street in Mayfair, London. She was the first child of The Duke and Duchess of York, who later became King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. At the time she stood third in line of succession to the throne after Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII), and her father, The Duke of York. But it was not expected that her father would become King, or that she would become Queen. The Duke and Duchess of York with Princess Elizabeth The Queen’s early life The Princess was christened Elizabeth Alexandra Mary in the private chapel at Buckingham Palace. She was named after her mother, while her two middle names are those of her paternal great-grandmother, Queen Alexandra, and paternal grandmother, Queen Mary. The Princess's early years were spent at 145 Piccadilly, the London house taken by her parents shortly after her birth, and at White Lodge in Richmond Park. She also spent time at the country homes of her paternal grandparents, King George V and Queen Mary, and her mother's parents, the Earl and Countess of Strathmore. In 1930, Princess Elizabeth gained a sister, with the birth of Princess Margaret Rose. The family of four was very close. The Queen’s early life When she was six years old, her parents took over Royal Lodge in Windsor Great Park as their own country home. Princess Elizabeth's quiet family life came to an end in 1936, when her grandfather, King George V, died. -

The Depression Affected Lehi Business by Richard Van Wagoner

The Depression affected Lehi Business By Richard Van Wagoner The 1920’s brought good fortune to most Lehi citizens as well as to Americans across the country. People called it the “Coolidge prosperity” in honor of U.S. President Calvin Coolidge. But the halcyon decade ended in fear and anxiety. The worst economic downturn in world history, known as the Great Depression began in October 1929, when stock values plunged into dramatically. Thousands of investors lost vast sums of money. Banks, factories, and stores closed, leaving millions of Americans penniless and jobless.. Until 1942, and the upsurge of war industries, the country and most of the world remained in the worst and longest period of high unemployment and low business productivity in modern times. Republican President Herbert Hoover believing in limiting the power of federal government enacted few measure to deal with the floundering economy. Near the end of his administration, Congress approved Hoover’s most successful antidepression measure: the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). Most Americans, however felt that Hoover was not doing enough to bolster the economy and elected Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. Roosevelt convinced that it was the government’s obligation to end the Depression called Congress into a special session to erect laws to reach this goal. The programs which evolved from these efforts were called the New Deal. Laws established under New Deal legislation had three main purposes: to provide relief for the needy, to create jobs and encourage business expansion, and to reform business and government practices to prevent further depressions. The Depression affected Lehi citizens in a multitude of ways. -

Fall 2020 Newsletter

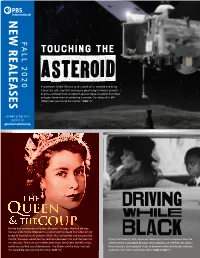

NEW REALEASES FALL 2020 FALL ASTEROIDTouching THE If spacecraft OSIRIS-REx can grab a piece of an asteroid and bring it back to Earth, scientists could gain great insight into our planet’s origins—and even how to defend against rogue asteroids. But NASA only gets three shots at collecting a sample. Can they pull it off? NOVA takes you inside the mission. 1x60 HD Screen programs online at pbsinternational.org THE QUEEN & THE COUP On the fi rst anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II’s reign, she had no idea she was about to be deployed in a secret plot to topple Iran’s democratic leader in favor of an all-powerful Shah. Planned by MI6 and executed by the CIA, the coup would destroy relations between Iran and the West to Driving While Black: Race, Space and Mobility in America explores how the this very day. The truth was hidden even from the Queen herself. Using advent of the automobile brought new mobility and freedom for African newly declassifi ed secret documents, The Queen and the Coup unravels Americans but also exposed them to discrimination and deadly violence, this incredible story for the fi rst time.1x47 HD and how that history resonates today. 1x60, 1x120 HD CURRENT AFFAIRS U.S. ELECTION 2020 The Choice 2020: Trump vs. Biden COURTESY OF STEPHEN LAM/REUTER In the midst of a historic pandemic, economic hardship, and a reckoning with racism, this November Americans will decide who will lead the nation for the next four years: President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden. -

King's Speech

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION 2010 BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY David Seidler THE KING'S SPEECH Screenplay by David Seidler See-Saw Films/Bedlam Productions CARD: 1925 King George V reigns over a quarter of the world’s population. He asks his second son, the Duke of York, to give the closing speech at the Empire Exhibition in Wembley, London. INT. BBC BROADCASTING HOUSE, STUDIO - DAY CLOSE ON a BBC microphone of the 1920's, A formidable piece of machinery suspended on springs. A BBC NEWS READER, in a tuxedo with carnation boutonniere, is gargling while a TECHNICIAN holds a porcelain bowl and a towel at the ready. The man in the tuxedo expectorates discreetly into the bowl, wipes his mouth fastidiously, and signals to ANOTHER TECHNICIAN who produces an atomizer. The Reader opens his mouth, squeezes the rubber bulb, and sprays his inner throat. Now, he’s ready. The reader speaks in flawless pear-shaped tones. There’s no higher creature in the vocal world. BBC NEWS READER Good afternoon. This is the BBC National Programme and Empire Services taking you to Wembley Stadium for the Closing Ceremony of the Second and Final Season of the Empire Exhibition. INT. CORRIDOR, WEMBLEY STADIUM - DAY CLOSE ON a man's hand clutching a woman's hand. Woman’s mouth whispers into man's ear. BBC NEWS READER (V.O.) 58 British Colonies and Dominions have taken part, making this the largest Exhibition staged anywhere in the world. Complete with the new stadium, the Exhibition was built in Wembley, Middlesex at a cost of over 12 million pounds. -

Agony and Ecstasy the Dramatic Life of Wallis Simpson

Agony and Ecstasy The Dramatic Life of Wallis Simpson Avalon French “A women’s life can really be a succession of lives, each revolving around some emotionally compelling situation or challenge, and each marked off by some intense experience.” Wallis Simpson 1956 Adultery! Espionage! Gambling! Ménage a trios! Drug dealing! Fascism! Abortions! Sexual Domination! Nazi Sympathizing! These are but a few of the explosive rumors that plagued the notorious Wallis Simpson throughout her adventurous lifetime. Was this modestly attractive, middle class debutant from Baltimore capable of igniting all the intrigue for which she was accused or was she simply an unwitting ingénue whose life was characterized by epic upheaval? As a young girl with her nose pressed against the window of Baltimore’s elite upper class, Wallis Simpson longed for a life of luxury and fame. By 1936 she had exceeded even her own expectations. No longer a smaller player at the edge of society circles, Wallis took center stage as the American divorcee who captured the heart of England’s dashing prince and future king. While some saw her as the unlikely starlet of a fairytale romance, many others reviled her as a scheming opportunist who brought disgrace to England’s royal family and caused a constitutional crisis within the British government. By all accounts, Wallis Simpson remains one of the world’s most scandalous women. Wallis Simpson, born Bessie Wallis Warfield in 1895, grew up in Baltimore with her widowed mother and wealthy uncle. Wallis attended Oldfields School, paid for with her Uncle’s money. Oldfields was a private, all girls boarding school from which she 1 graduated in 1914. -

Winter-Spring PMA Newsletter 2018 Revised for The

Preserving the Unique History of Petaluma and Providing Educational and Cultural Services to the Community Quarterly Newsletter P ETALUMA EGG DAY Winter/Spring 2018 VOLUME 28, ISSUE 1 1 On the Cover by John Benanti Petaluma Museum Association Board “The World’s Egg Basket” Executive Officers HIS YEAR’S BUTTER and Egg Day celebration continues a long President: Kathy Fries tradition of remembering our city’s history. The current Vice President: TBD Tcelebration traces its beginning to the early 1980’s, but it has Treasurer: Erica Barlas, CPA a history that takes it back to the end of World War I. The history of Recording Secretary: Debbie celebrating agriculture in Petaluma goes back even further. Countouriotis On September 26, 1867 the first exhibition of the Sonoma County Directors: Agricultural Society took place at the fairgrounds. No, not those Clint Gilbert fairgrounds where the Sonoma-Marin is held each year, but the Rob Girolo fairgrounds in the area where Petaluma High School is today. The Kate Hawker street the high school is on is a reminder of where the first fair was Dianne Ledou in 1867. Part of the reason the fair was located there was the Freyda Ravitz availability of water. A natural spring which provided much of the Michael Slade town’s water was located in the area, near the corner of Douglas and Elizabeth Walter Spring Streets. Thus the name Spring Street. Marshall West Over the years that followed, up to the period of WWI, fairs and exhibitions celebrating the town’s agricultural history took place Parks & Recreation Dept. -

![1936-12-24 [P A-3]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7113/1936-12-24-p-a-3-2587113.webp)

1936-12-24 [P A-3]

Eight-Foot Snake in Refuse Can V New Low-Rent, . House DRIVE TO BE MADE Apartment Creates Furor on Trash Truek ON SOCIAL DISEASE Three-Story Structure for Delegates From 32 States Expropriating Large Landed * 31 Colored Families in and D. C. to Meet Estates Defended, but In- Alley Drive. Her# Monday. vestors Reassured. The first (Coprrlsht.. 1936. By the The Alley Dwelling Authority, which organised Nation-wide ef- Associated Press.; recently dedicated the newly com- fort to combat the inroads of syphilis MEXICO CITY, December 24.— and on pleted Hopkins place project, an- gonorrhea the health of Amer- President Lazaro Cardenas of Mexico ican citizens will be launched in an Interview reaffirmed nounced today its approval of plans by his govern- Gen. Thomas to construct a three-story apartment Surg. Parran, chief of ment’s determination to help Mexico’! the United States Public Health Serv- house for 31 colored families on a working classes better their standard in a site extending from Blands alley to W ice, three-day conference here, of living. street, between Second and Fourth beginning Monday. The meetings He defended his policy of expro- streets. will be held in the Department of priating and dividing great landed Commerce A low bid for this building was $112.- Auditorium. estates because of its "benefits to th* 425. submitted by Beauchamp & King. More than 300 delegates from 32 people,” but assured foreign investors This is a saving of $31,212 on the low States and the District of Columbia they need not fear lack of guarantees Architect’s drawing of the newest apartment house to be erected by the Alley Dwelling in Mexico. -

Ppy2783998594

VA Foundation for the Humanities | PPY2783998594 ED: This podcast is supported by Progressive. On average, customers who switched to progressive save $668 a year on car insurance. Start a quote online and start saving today at progressive.com. BRIAN: Major funding for BackStory is provided by the anonymous donor, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of Virginia, the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, and the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation's. JOANNE: From Virginia Humanities, this is BackStory. BRIAN: Welcome to BackStory, the show that explains the history behind today's headlines. I'm Brian Balogh. JOANNE: I'm Joanne Freeman. ED: And I'm Ed Ayers. BRIAN: An English prince has his heart set on it American actress. On May 19th, 2018, Prince Harry of Wales is set to marry California native, Meghan Markle. When the couple's relationship became public, the press coverage was so intense and so negative that the royal family issued an official statement warning the press off. MALE SPEAKER: The Royals rarely talk about their love lives, but Prince Harry just confirmed that he is dating American actress, Meghan Markle. FEMALE Yeah, he broke the news in order to slam the press. He is royally upset about the way his SPEAKER: girlfriend is being treated, calling it-- FEMALE Abuse and harassment, racial undertones, outright sexism and racism of social media trolls. SPEAKER: Megan's father is white, her mother is African-American. MALE SPEAKER: The private life has to be private. JOANNE: But this is not the first transatlantic royal relationship and Meghan Markle is not the first American woman to become a tabloid sensation after getting involved with a British Royal.