Read Book Animalium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aristotelian Influence in the Formation of Medical Theory

Aristotelian influence in the formation of medical theory Mythologic cradle of Greek medical thought Early Greek medicine contained both natural and supernatural elements. Pharmaka, a broad term for drugs, referred to applications for magic, for poison, and for curing. The gods had a large role. The Iliad opened with an epidemic sent by Apollo, and medical solutions were often a search to discover what offended a particular god. By the time of Hesiod (~700 B.C.), Asclepian healing ceremonies consisted of a normalized set of rituals involving abstinence from food and wine, a sacrifice or gift to the god, and a nocturnal “incubational” period.1 Aristotle stood at the portal between mythical and modern horizons of thought, and was a prime motivating agent in propelling medicine, not just philosophy, through that portal. As a natural philosopher, Aristotle’s influence on medicine is two-pronged – first in terms of immediate causation – his influence on his own students and their intellectual descendents – and secondly in terms of indirect causation – his influence on medical debates raging today. The shift The Sicilian philosopher (and some speculate physician) Empedocles, whose life straddled the sixth and fifth centuries B.C., is credited with the notion that everything existing is composed of four elements – earth, air, fire, and water.2 Alcmaeon of Croton (~470 B.C.) held to a similar natural scheme, claiming an equality of powers is responsible for health – moist and dry; cold and hot; bitter and sweet. An interesting schism over this model developed with which Aristotle was to contend. Following Empedocles’ lead, Plato ascribed to a four-element theory, having placed emphasis on universal principles, including the Forms. -

Harvey, Clinical Medicine and the College of Physicians

n MEDICAL HISTORY Harvey, clinical medicine and the College of Physicians Roger French † Roger French ABSTRACT – This article deals with the problems one of the principal therapeutic techniques of the D Phil, Former of seeing Harvey historically, rather than as a time, phlebotomy. For these and related reasons, Lecturer in the construction seen from the viewpoint of modern medicine was in a crisis as Harvey grew old, and History of medicine. It deals with his programme of work, when he died, in 1657, although the circulation of Medicine, Fellow of the expectations of his audience, his intellectual the blood was largely accepted, medicine itself was Clare Hall, training and the political and religious circum- very different 2. University of stances of seventeenth century Europe. It shows Cambridge that at the time the impact of Harvey’s discovery Medicine and history Clin Med JRCPL was negative on clinical medicine and its theory, 2002;2:584–90 but also shows ways in which that impact was In fact Harvey’s discovery exemplifies, perhaps in an favourable. extreme form, the problem of dealing historically with medical progress, that is, of evaluating it in its KEY WORDS: Aristotelianism, circulation, own terms. The discovery of the circulation was so Galenism, natural philosophy, seventeenth important that historians used to be especially century culture concerned with Harvey’s methods 3. More recently they have contrasted Harvey’s approach with the Introduction reluctance of those of his colleagues to see the truth – that is, the circulation – when it was made apparent This year it is four hundred years since the to them. -

Four Treatises of Theophrastus Von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus

510 NATURE MAY 9, 1942, VoL. 149 I regret that the juncture between the new theory dogmas of this physician born two thousand years of reaction rates and the 'electronic theory' of Flurs later. heim, Lapworth, Robinson and Ingold still does not The book under review, the first modem trans seem very close. The future valuation of the new lation into English of any works of Paracelsus, is a ideas may largely depend on the extent to which they labour of love to mark the four-hundredth anniver will prove able to explain more of the remarkable sary of his death. Like all such labours it has been rules which the organic chemist has discovered and carefully and well done by the four collaborators. has not yet related with any degree of precision to From it the reader may gather both the merits and the interplay of atomic forces. faults of "Lutherus medicorum", as Paracelsus was In the light of present achievement and in the styled, his interest in drugs, occupational diseases hope of further advance, we may recall for a moment and psychiatry, his self-assurance, conceit and the general expectations which have been enter tendency to wild speculation. The fourth treatise of tained on the subject of theoretical chemistry for the the book is scarcely medical at all, but throws light last thirty years or so. It was about 1912 that I on the mystic belief in sylphs, nymphs, pygmies and first heard it said in jest, that "You need not bother salamanders, the spirits living in the four so-called any longer to leam chemistry, because soon it will elements. -

Medicine in the Renaissance the Renaissance Was a Period of Many

Medicine in the Renaissance The Renaissance was a period of many discoveries and new ideas. Students need to be able to establish whether these discoveries led to improvements in the way that people were treated. Did the ideas of medical greats such as Vesalius, Harvey and Pare result in immediate, gradual or no improvements? William Harvey William Harvey became Royal Physician to James I and Charles I. He was a leading member of the Royal College of Surgeons and trained at the famous university in Padua, Italy. Harvey's contribution to medical knowledge was great but the impact of his work was not immediate. In 1615 he conducted a comparative study on animals and humans. He realised that many of his findings on animals could be applied to Humans. Through this study he was able to prove that Galen had been wrong to suggest that blood is constantly being consumed. Instead, he argued, correctly, that blood was constantly pumped around the body by the heart. Harvey went on to identify the difference between arteries and veins and noted that blood changes colour as it passes through the lungs. Harvey also identified the way in which valves work in veins and arteries to regulate the circulation of blood. An ilustration of William Harvey's findings. Source - wikimedia. Andreas Vesalius Vesalius was born into a medical family and was encouraged from an early age to read about medical ideas and practice. He went to Louvain University from 1528 to 1533 when he moved to Paris. Vesalius returned to Louvain in 1536 because of war in France. -

Arrested Development, New Forms Produced by Retrogression Were Neither Imperfect Nor Equivalent to a Stage in the Embryo’S Development

Retrogressive Development: Transcendental Anatomy and Teratology in Nineteenth- Century Britain Alan W.H. Bates University College London Abstract In 1855 the leading British transcendental anatomist Robert Knox proposed a theory of retrogressive development according to which the human embryo could give rise to ancestral types or races and the animal embryo to other species within the same family. Unlike monsters attributed to the older theory of arrested development, new forms produced by retrogression were neither imperfect nor equivalent to a stage in the embryo’s development. Instead, Knox postulated that embryos contained all possible specific forms in potentio. Retrogressive development could account for examples of atavism or racial throwbacks, and formed part of Knox’s theory of rapid (saltatory) species change. Knox’s evolutionary theorizing was soon eclipsed by the better presented and more socially acceptable Darwinian gradualism, but the concept of retrogressive development remained influential in anthropology and the social sciences, and Knox’s work can be seen as the scientific basis for theories of physical, mental and cultural degeneracy. Running Title: Retrogressive Development Key words: transcendentalism; embryology; evolution; Robert Knox Introduction – Recapitulation and teratogenesis The revolutionary fervor of late-eighteenth century Europe prompted a surge of interest in anatomy as a process rather than as a description of static nature. In embryology, preformation – the theory that the fully formed animal exists -

Soul: the Form of a Living Thing

Early mechanist ideas in biology: Harvey, Descartes, and Boyle It all starts with Aristotle! 384-322 BCE • Essentialism • 'hylomorphic' view — hylê 'matter', morphê 'form, shape‘ • bronze sphere: bronze matter and spherical form • Ax: wood and iron (matter) and the shape and organization required for chopping •Form: – More than mere shape – Realization of potentiality that specifies essence Soul: the form of a living thing • Three types of soul – Vegetative: nutrition, growth and reproduction: botany – Animal: add sensation and locomotion: zoology – Rational: add 'intellect' or 'thinking of' (nous) • Soul imposes form on matter—in nutrition: "the active principle of growth lays hold of an acceding food which is potentially flesh and converts it into actual flesh." • More precisely: different forms in different species and genera – Separated cetaceans (marine mammals) from fish and identified them as more like mammals • Life birth 1 Aristotelian classification Animals Without blood With blood cephalopods (e.g., octopus) Viviparious (live-bearing) crustaceans quadrupeds (mammals) insects (including also spiders, Birds scorpions, and centipedes) Oviparous (egg-laying) shelled animals (e.g., molluscs quadrupeds (reptiles and and echinoderms) amphibians) "zoophytes" or plant-animals Fishes (e.g., cnidarians) Whales Aristotle’s Anatomy and Physiology • Digestive system converted food into blood by the action of heat • Breathing functioned mainly to cool the body • Kidneys cleansed the body of wastes • The heart generated the heat required to turn food into blood • The heart also represented the location of the human mind, the source of intellect, consciousness, emotions, and motivations • The brain contributed to cooling of the body Aristotle’s Four “Causes”: Aitia • Material: that out of which something is, e.g. -

Origins of Systems Biology in William Harvey's Masterpiece On

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 1658-1669; doi:10.3390/ijms10041658 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Molecular Sciences ISSN 1422-0067 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Communication Origins of Systems Biology in William Harvey’s Masterpiece on the Movement of the Heart and the Blood in Animals Charles Auffray 1,* and Denis Noble 2 1 Functional Genomics and Systems Biology for Health, CNRS Institute of Biological Sciences - 7, rue Guy Moquet, BP8, 94801 Villejuif, France 2 Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, Balliol College, Oxford University, Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PT, United Kingdom. E-Mail:[email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel. +33-1-49583498; Fax: +33-1-49583509 Received: 20 March 2009; in revised form: 13 April 2009 / Accepted: 14 April 2009 / Published: 17 April 2009 Abstract: In this article we continue our exploration of the historical roots of systems biology by considering the work of William Harvey. Central arguments in his work on the movement of the heart and the circulation of the blood can be shown to presage the concepts and methods of integrative systems biology. These include: (a) the analysis of the level of biological organization at which a function (e.g. cardiac rhythm) can be said to occur; (b) the use of quantitative mathematical modelling to generate testable hypotheses and deduce a fundamental physiological principle (the circulation of the blood) and (c) the iterative submission of his predictions to an experimental test. -

Progressive Reactionary: the Life and Works of John Caius, Md

PROGRESSIVE REACTIONARY: THE LIFE AND WORKS OF JOHN CAIUS, MD by Dannielle Marie Cagliuso Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Dannielle Marie Cagliuso It was defended on July 20, 2015 and approved by Dr. Peter Distelzweig, Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy (University of St. Thomas) Dr. Emily Winerock, Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History Dr. Janelle Greenberg, Professor, Department of History Thesis Director: Dr. James G. Lennox, Professor and Chair, Department of History and Philosophy of Science ii Copyright © by Dannielle Marie Cagliuso 2015 iii PROGRESSIVE REACTIONARY: THE LIFE AND WORKS OF JOHN CAIUS, MD Dannielle Marie Cagliuso, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2015 The picture of Dr. John Caius (1510-1573) is fraught with contradictions. Though he had an excellent reputation among his contemporaries, subsequent scholars tend to view him more critically. Caius is frequently condemned as a reactionary and compared unfavorably to his more “progressive” contemporaries, like Conrad Gesner and Andreas Vesalius. This approach to Caius is an example of what I term “progressivist history,” a prevalent but problematic trend in historical scholarship. Progressivist history applies a progressive-reactionary dichotomy to the past, splitting people and events into two discrete camps. By exploring the life and works of John Caius and comparing him to some of his “progressive” contemporaries, I reveal why this dichotomy is problematic. It treats both the progressive “heroes” and reactionary “villains” unfairly in that it fails to appreciate the agency of each individual and the nuanced differences between them. -

William Harvey, M.D.: Modern Or Ancient Scientist? Herbert Albert

[Loyola Book Comp., run.tex: 0 AQR–Vol. W–rev. 0, 14 Nov 2003 ] [The Aquinas Review–Vol. W–rev. 0: 1 14 Nov 2003, 4:02 p.m.] . The Aquinas Review, Vol. III, No. 1, 1996 William Harvey, M.D.: Modern or Ancient Scientist? Herbert Albert Ratner, M.D.ý William Harvey was born in England in 1578 and died in 1657. He received his grammar school education at the famous King’s School in Canterbury. In 1593 he en- tered Caius College, Cambridge, and received his B.A. degree in 1597. In this period, it was not unusual for English Protestants interested in a scientific education to seek it in a continental Catholic university. Harvey chose the Universitas Juristarum, the more influential of the two universities which constituted the University of Padua in Italy and which had been attended by Thomas Linacre and John Caius, and where, incidentally, the Dominican priests were associated with University functions. Competency in the traditional studies of the day was characteristic of William Harvey’s intellectual develop- ment. The degree of Doctor of Physic was awarded to Harvey in 1602 with the unusual testimonial that ‘‘he had conducted himself so wonderfully well in the examina- tion, and had shown such skill, memory, and learning that he had far surpassed even the great hopes which his Dr. Ratner, a philosopher of medicine, is Visiting Professor of Com- munity and Preventive Medicine, New York Medical College, and editor of Child and Family. This article was originally published as one of a series in a special issue of The Thomist, Volume XXIV, Nos. -

91 on Page 91 of His Brilliant Book, Domenico Bertoloni Meli Presents

_full_journalsubtitle: A Journal for the Study of Science, Technology and Medicine in the Pre-modern Period _full_abbrevjournaltitle: ESM _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 1383-7427 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1573-3823 (online version) _full_issue: 1 _full_issuetitle: The Body Politic from Medieval Lombardy to the Dutch Republic _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Book Reviews _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (rechter kopregel - mag alles zijn): Book Reviews _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Early Science and Medicine 25 (2020) 91-93 Book Reviews 91 Domenico Bertoloni Meli (2019), Mechanism: A Visual, Lexical, and Conceptual History (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press), pp. xii + 188, illus., $45.00 (hardcover), ISBN 978 0 8229 4547 5. On page 91 of his brilliant book, Domenico Bertoloni Meli presents Robert Hooke’s investigation of the striking phenomenon of the beard of wild oats as an example of the latter’s attempt to tie together natural and artificial devices: not only could plants be mechanized and explained through mechanical in- struments, but “Hooke was [also] inspired by this mechanism occurring in na- ture to construct a hybrid device to measure humidity” (pp. 91-92). By contrast, several years after the publication of Hooke’s Micrographia, with its explana- tions of the wild oat or the sensitive herb, Leibniz continued questioning the possibility of mechanizing plants insofar as these have no motion. In fact, within the all-pervasive paradigm of the mechanical philosophy, early modern attempts at mechanizing all natural phenomena appear to have been much more contested and problematic than one might have expected. -

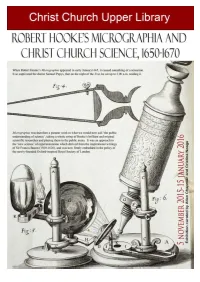

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

A Prodigious Namer of Nature

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS “Chymistry”, as prac- tised by Robert Boyle and other natural philosophers, was then evolving from NHM LONDON/SPL medieval alchemy to modern chemistry. It sought the transmu- tation of base metals into gold even as it was The Wonderful Mr Willughby: harnessed for applica- The First True tions such as weapons Ornithologist manufacture. Eventu- TIM BIRKHEAD ally, Willughby and Bloomsbury (2018) Ray criss-crossed England and Wales on their birding and plant-hunting expeditions. Around 1662, they set themselves an ambitious goal: observing, describing and classifying all species. They felt that both the literature and the nomenclature sowed con- fusion. Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner’s History of Animals (1551–58), for instance, mixed ancient knowledge with observation. By contrast, Ray and Willughby grounded their system in precise anatomical descrip- tion, distinguishing between even closely related species. Beginning with British spe- cies and extending to mainland Europe, they A peacock and (below) a established a taxonomy that would be built dodo from Francis Willughby’s on by centuries of naturalists, including Carl 1676 Ornithologiae libri tres. Linnaeus in the mid-eighteenth century. Dividing birds into land and water fowl, they NATURAL HISTORY deployed attributes such as beak shape to create a branching classification key. Willughby thrived on collaboration, and used his wealth to enable it. In 1662, Ray A prodigious resigned his college fellowship, rather than subscribe to the Act of Uniformity passed by Parliament to fortify Charles II’s newly restored monarchy. Willughby invited his namer of nature mentor into his household. The next year, Willughby was elected an “original fellow” of the Royal Society, and he and Ray, with Elizabeth Yale relishes a biography of a seventeenth- Ray’s students Philip Skippon and Nathaniel century polymath with a notable gift for collaboration.