The Death Penalty Moratorium Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Our Full Report, Death in Florida, Now

USA DEATH IN FLORIDA GOVERNOR REMOVES PROSECUTOR FOR NOT SEEKING DEATH SENTENCES; FIRST EXECUTION IN 18 MONTHS LOOMS Amnesty International Publications First published on 21 August 2017 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2017 Index: AMR 51/6736/2017 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 ‘Bold, positive change’ not allowed ................................................................................ -

Watermark W Atermark

WATERMARK A SCHOLARLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH AT CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LONG BEACH 8 WATERMARK 8 WATERMARK SPRING 2014 Watermark accepts submissions annually between October and February. We are 8 WWW WWW dedicated to publishing original critical and theoretical essays concerned with literature of all genres and periods, as well as works representing current issues Editor ∙ in the fields of rhetoric and composition. Reviews of current works of literary Mary Sotnick criticism or theory are also welcome. Managing Editors ∙ Rusty Rust Jaime Rapp All submissions must be accompanied by a cover letter that includes the author’s ∙ name, phone number, email address, and the title of the essay or book review. All essay submissions should be approximately 12-15 pages and must be typed American Literature Editors Levon Parseghian ∙ Shouhei J. Tanaka ∙ Amy Desusa in MLA format with a standard 12 pt. font. Book reviews ought to be 750-1,000 words in length. As this journal is intended to provide a forum for emerging British Literature Editors voices, only student work will be considered for publication. Submissions will Bethany Acevedo not be returned. Please direct all questions to [email protected] and address all submissions to: Ethnic American Literature Jaime Rapp ∙ Rusty Rust ∙ Phương Lưu Department of English: Watermark California State University, Long Beach Rhetoric & Composition Editors 1250 Bellflower Boulevard Dya Cangiano Long Beach, CA 90840 Medieval & Renaissance Studies Editors Visit us -

Reason #1 to Support a National Moratorium on Executions

Reason #1 to Support a National Moratorium on Executions The National Death Penalty System is Seriously Flawed Resulting in Wrongful Convictions and Death Sentences • More than two out of every three capital judgments reviewed by the courts during a 23-year period were seriously flawed. Experts reviewed all the capital cases and appeals imposed in the United States between 1973 and 1995 at the state and federal levels. They found a national error rate of 68%. In other words, over two-thirds of all capital convictions and sentences are reversed because of serious error during trial or sentencing. This does not include errors that were not serious enough to warrant a reversal. • The federal government would not tolerate an error rate of 68% for any other government function - such as product safety or processing social security claims. Yet it allows this margin of error in the system that can take a person’s life. Only a moratorium puts an immediate halt to the risk of an innocent person being executed. • The error rate for capital cases is much higher than for other types of cases. At the direct appeal stage, serious or reversible error is detected in about 12 to 20% of the non-capital criminal cases that are appealed. • High error rates exist throughout the country and are not limited to certain states. Over 90% of states that have the death penalty have error rates of 52% or higher. 85% have error rates of 60% or higher. Three- fifths have error rates of 70% or higher. This is not an isolated problem but is universal in all death penalty states. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Sacred Heart University Review Volume 20 Issue 1 Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Article 1 Numbers 1 & 2, Fall 1999/ Spring 2000 2000 The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Helen Prejean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview Recommended Citation Prejean, Helen (2000) "The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking," Sacred Heart University Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SHU Press Publications at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sacred Heart University Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Cover Page Footnote This is a lightly edited transcription of the talk delivered by Sister Prejean at Sacred Heart University on October 31, 2000, sponsored by the Hersher Institute for Applied Ethics and by Campus Ministry. This article is available in Sacred Heart University Review: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 Prejean: The Journey of Dead Man Walking SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, C.S.J. The Journey of Dead Man Walking I'm glad to be with you. I'm going to bring you with me on a journey, an incredible journey, really. I never thought I was going to get involved in these things, never thought I would accompany people on death row and witness the execution of five human beings, never thought I would be meeting with murder victims' families and accompanying them down the terrible trail of tears and grief and seeking of healing and wholeness, never thought I would encounter politicians, never thought I would be getting on airplanes and coming now for close to fourteen years to talk to people about the death penalty. -

An Interview with Jake Heggie

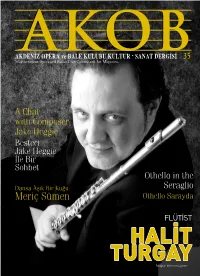

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

839 Was Also a Conservative Romantic, a Trait That Became Particularly Pronounced in His Second World War Columns

Comptes rendus / Book Reviews 839 was also a conservative romantic, a trait that became particularly pronounced in his Second World War columns. Writing of British naval valour, he proclaimed that “the spirit of Elizabethan days has come back to these islands once more.” (p. 131) His tone became more muted after the war, when the Labour Party which he despised came to power and implemented many of the provisions of the 1942 Beveridge Report. Baxter was vehemently opposed to socialism and the welfare state, siding decisively with the former in what he called the “battle of the individual against the state” (p. 242). His most evocative columns, however, such as that on the 1936 Abdication crisis, brought home to Canadians those events gripping what many still saw as the “mother dominion.” If I had one reservation about the book, it is that Baxter and the Canadian connection sometimes fades from view as Thompson sets out the context of successive British high political dramas. More might also be said about how, and in what ways, the ideas and sentiments Baxter espoused in his London Letters were received by his Maclean’s readers. Thompson gives us circulation numbers which attest to the magazine’s self-proclaimed status as “Canada’s National Magazine,” but how Baxter’s ideas shaped Canadians’ political, economic, social and cultural activities is left mostly unsaid. Nonetheless, this is a fine book, closely researched and carefully written. It is particularly strong on Baxter during the appeasement years, reflecting Thompson’s expertise in this period. Historians of the British world would benefit greatly from more transnational studies in the model of Thompson’s work on Beverley Baxter. -

74 Literary Journalism Studies

74 Literary Journalism Studies Photo by Barbara Gandolfo-Frady 75 “Just as I Am”? Marshall Frady’s Making of Billy Graham Doug Cumming Washington and Lee University, United States Abstract: Literary journalists have a dual role that more or less inevitably presents a moral problem. They must establish a relationship with their sub- ject, and then must shift their attention and loyalty to their art—the writing of the work. Marshall Frady (1940–2004), a journalist with a zeal for the literary side of the balance that drew on Southern writers such as Faulkner and Agee, published evocative profiles of numerous subjects in national magazines and novelistic biographies. Nowhere was the moral problem more troubling than when Frady, the son of a Southern Baptist preacher, took on world-renowned evangelist Billy Graham in a biography he spent at least five years working on. The following paper is based on Frady’s personal papers, recently acquired by Emory University in an IRS auction. moral conundrum at the heart of literary journalism is the writer’s rela- A tionship with his or her main character. The writer of this higher order of nonfiction needs to get inside the head of the individual or individuals being written about. This relationship-to-source is different from that of the newsroom correspondent. That more common journalistic relationship has its own set of ethical and legal complexities, balancing protection of a source against a public interest in disclosure.1 But for the literary journalist, the main source of information is usually the story’s subject as well, unless the work’s central figure is never interviewed. -

Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process 00 Coyne 4E Final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page Ii

00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page i Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page ii Carolina Academic Press Law Advisory Board ❦ Gary J. Simson, Chairman Dean, Mercer University School of Law Raj Bhala University of Kansas School of Law Davison M. Douglas Dean, William and Mary Law School Paul Finkelman Albany Law School Robert M. Jarvis Shepard Broad Law Center Nova Southeastern University Vincent R. Johnson St. Mary’s University School of Law Peter Nicolas University of Washington School of Law Michael A. Olivas University of Houston Law Center Kenneth L. Port William Mitchell College of Law H. Jefferson Powell The George Washington University Law School Michael P. Scharf Case Western Reserve University School of Law Peter M. Shane Michael E. Moritz College of Law The Ohio State University 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page iii Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process fourth edition Randall Coyne Frank Elkouri and Edna Asper Elkouri Professor of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Lyn Entzeroth Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs University of Tulsa College of Law Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page iv Copyright © 2012 Randall Coyne, Lyn Entzeroth All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-1-59460-895-7 LCCN: 2012937426 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page v Summary of Contents Table of Cases xxiii Table of Prisoners xxix List of Web Addresses xxxv Preface to the Fourth Edition xxxvii Preface to the Third Edition xxxix Preface to the Second Edition xli Preface to the First Edition xliii Acknowledgments xlv Chapter 1 • The Great Debate Over Capital Punishment 3 A. -

Read the Case Summaries

Reasonable Doubts: Is the U.S. Executing Innocent People? October 26, 2000 A Preliminary Report of the GRASSROOTS INVESTIGATION PROJECT Quixote Center Pursuing justice, peace, and equality P.O Box 5206, Hyattsville, MD 20722 301-699-0042 / [fax] 301-864-2182 / www.quixote.org / [email protected] Table of Contents I. Acknowledgements II. Introduction III. Methodology IV. Findings V. Conclusion VI. Recommendations VII. The Case Summaries Alabama Brian K. Baldwin Cornelius Singleton Freddie Lee Wright California Thomas M. Thompson Florida James Adams Willie Jasper Darden, Jr. Jesse J. Tafero Illinois Girvies Davis Missouri Larry Griffin Roy Michael Roberts Texas Odell Barnes, Jr. Robert Nelson Drew Gary Graham (aka Shaka Sankofa) Richard Wayne Jones Frank Basil McFarland 1 Virginia Roger Keith Coleman VIII. Appendices – Case Charts Brian K. Baldwin Cornelius Singleton Freddie Lee Wright Thomas M. Thompson James Adams Willie Jasper Darden, Jr. Jesse J. Tafero Girvies Davis Larry Griffin Roy Michael Roberts Odell Barnes, Jr. Robert Nelson Drew Gary Graham (aka Shaka Sankofa) Richard Wayne Jones Frank Basil McFarland Roger Keith Coleman 2 Acknowledgements Equal Justice USA would like to express its utmost gratitude to Claudia Whitman, who had the idea, the passion, and the brilliance to see this project from inception to conclusion. We thank Lisa Kois, Esq. for her assistance in drafting the report, and David Hammond, Esq. who assisted with research. We also thank the many people throughout the country who have given their time and talents to the project, including: Rob Owen, Rob Warden, Micki Dickoff, Rita Barker, Bill Lofquist, Bruce Livingston, Kent Gipson, Margaret Vandiver, Mike Radelet, Esther Brown, Judy Cumbee, Jill Keefe, Laird Carlson, Barbara Taylor, Matt Holder, Dawn Dye, Bob and Marie Long, Grace Bolden, and Wendy Fancher. -

Dalrev Vol24 Iss4 Backmatter.Pdf

. DALHOUSIE REVIEW I- . .COAST · · to· · ··COAST ~;( Canadian Pacific Hotels are locate-d in many of the important eentres across Canada. They are designed especially for the comfort and convenience of their guests. MeAd.a.m Hotel-McAdam, N . B. Hotel Palliser-Calgary, Alta. Cornwallis Inn-Kentville, N. S. The Empress Hotel-Victoria, B. C. Chateau Frontenac-Quebec, Que. Hotel Vancouver-Vancouver, B. C. Royal York Hotel-Toronto, Ont. (Operated In · the Vancouver Hotel Royal Alexandra Hotel-Winnipeg, Company, Ltd., on behalf of the Canadian Pacific and OaoadJan Hotel Saskatchewan-Regina, Sask. National Rallways ''If I had the time?. ... Why Wait for That? Many a business executive has been heard to remark, 110ne of these days, when I have the time, I'm going to get out a. booklet", (or a folder, catalogue, or other form of printed matter, ;as the case may be). But time and inclination often prove elusive .in gredients-and meanwhile an aid to selling that 1might be doing profitable work stays uncreated. Busy executives can solve problems of this nature very readily by utilizing "Imperial" service. For we have on our staff men experienced in planning and writing all forms of "printed sales men". Their services are at all times available to !our clients. Enquiries welcomed and printing estimates supplied, No Obligation. The Imperial Publishing Company Limited P. 0. Box 459 Halifax, N. s . ii THE DALHOUSIE REVIEW Maintains a high standard of scholarship and the largest Staff, Libraries and Laboratories in Eastern Canada. ARTS AND SCIENCE FACULTY DEGREES: B.A.~ B.Sc., B.Com., B.Mus., Phm.B.