A Time to Mourn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincoln Square Synagogue for As Sexuality, the Role Of

IflN mm Lincoln Square Synagogue Volume 27, No. 3 WINTER ISSUE Shevat 5752 - January, 1992 FROM THE RABBI'S DESK.- It has been two years since I last saw leaves summon their last colorful challenge to their impending fall. Although there are many things to wonder at in this city, most ofthem are works ofhuman beings. Only tourists wonder at the human works, and being a New Yorker, I cannot act as a tourist. It was good to have some thing from G-d to wonder at, even though it was only leaves. Wondering is an inspiring sensation. A sense of wonder insures that our rela¬ tionship with G-d is not static. It keeps us in an active relationship, and protects us from davening or fulfilling any other mitzvah merely by rote. A lack of excitement, of curiosity, of surprise, of wonder severs our attachment to what we do. Worse: it arouses G-d's disappointment I wonder most at our propensity to cease wondering. None of us would consciously decide to deprive our prayers and actions of meaning. Yet, most of us are not much bothered by our lack of attachment to our tefilot and mitzvot. We are too comfortable, too certain that we are living properly. That is why I am happy that we hosted the Wednesday Night Lecture with Rabbi Riskin and Dr. Ruth. The lecture and the controversy surrounding it certainly woke us up. We should not need or even use controversy to wake ourselves up. However, those of us who were joined in argument over the lecture were forced to confront some of the serious divisions in the Orthodox community, and many of its other problems. -

From the Rabbi's Desk the Festival of Chanukah Retells the Struggle Between Traditional Judaism and the Forces of Secularism Which Seek to Engulf It

Vol. 3, Xo. 4 December, 1966 Kislev-Tevet, 5727 From The Rabbi's Desk The Festival of Chanukah retells the struggle between traditional Judaism and the forces of secularism which seek to engulf it. The Hellenists maintained that the esthetic values of Greek philosophy were far more noble than the outdated rituals of ancient Judea, that the dicta of Aristotle ought replace the laws of Moses. The one commandment most maligned was that of circumcision. How could civilized people, aware of the perfection of the human body, agree to any operation which would alter a physical organ? In truth, many of the Hellenized Jews underwent plastic surgery to conceal their "shameful" circumcision. Similarly in our own day is the rite of circum¬ cision being questioned and rejected. All too fre¬ quently a father asks me to name his new-born son in the synagogue after a so-called brit-milah was performed by a doctor on the third or fourth day after birth. So has twentieth century America trans¬ formed a religious imperative into a mere biological operation! The rite of circumcision brands our regenerative organ with the unescapable fact of our Jewishness. It declares to the son of Abraham at birth that the obligations and privileges of his Judaism are an intrinsic element of the very origin of his being. It eloquently preaches the power of man to perfect himself and the primacy of God over every aspect of man's physical existence. But most significantly it symbolizes commitment, the kind of commitment which involves the shedding of one's blood (hatafat dam brit) for one's faith and one's God. -

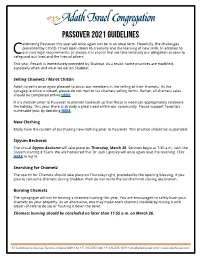

Passover 2021 Guidelines Elebrating Passover This Year Will Once Again Not Be in an Ideal Form

passover 2021 guidelines elebrating Passover this year will once again not be in an ideal form. Hopefully, the challenges presented by COVID-19 will open doors to creativity and the learning of new skills. In addition to Cour civic legal requirements, as always, it is crucial that we take seriously our obligation as Jews to safeguard our lives and the lives of others. This year, Pesach is immediately preceded by Shabbat. As a result, some practices are modified, especially when and what we eat on Shabbat. Selling Chametz / Ma’ot Chittin Adath Israel is once again pleased to assist our members in the selling of their chametz. As the synagogue office is closed, please do not mail or fax chametz selling forms. Rather, all chametz sales should be completed online HERE. It is a mitzvah prior to Passover to provide tzedakah so that those in need can appropriately celebrate the holiday. This year, there is already a great need within our community. Please support Toronto’s vulnerable Jews by donating HERE. New Clothing Many have the custom of purchasing new clothing prior to Passover. This practice should be suspended. Siyyum Bechorot The virtual Siyyum Bechorot will take place on Thursday, March 25. Services begin at 7:30 a.m., with the Siyyum starting 8:15am. We are honoured that Dr. Jack Lipinsky will once again lead the teaching. Click HERE to log in. Searching for Chametz The search for Chametz should take place on Thursday night, preceded by the opening blessing. If you plan to consume chametz during Shabbat, then do not recite the kol chamirah closing declaration. -

Shabbat Bulletin

SHABBAT BULLETIN Rabbi Barry Gelman The Eruv is up. Rabbi Emeritus Joseph Radinsky z’l Cantor Emeritus Irving Dean President Mr. Rick Guttman LOUIS AND LEAH YAFFEE BNEI AKIVA PROGRAM: Shabbat No Teen Minyan 10:30 am: Tot Shabbat 4:10 pm Snif Groups: 1st—3rd in the tot trailer, 4th—5th in the Sukkah, 6th in the teen minyan trailer Serving the Orthodox Community of Parents are asked to tell their kids that card playing is not permitted in Houston for over 100 years the Synagogue. The presence of card playing does not promote the type of atmosphere we are trying to create in the shul. Additionally, all November 4, 2017 youth should either be in groups or sitting with their parents. 22 Cheshvan 5778 In recognition of our appreciation for all the help we received Torah Sefer: Bereishit during Hurricane Harvey, UOS is sponsoring a Kiddush this Shabbat Parasha: Chayei Sarah at both Beth Rambam and Young Israel. Haftarah: I Kings 1:1-31 ————————————— Shabbat Kiddush with chicken The annual UOS Congregation Annual Meeting salad in Freedman Hall. will take place on Sponsored by April and Kobi Sunday, December 10, 2017 Amsalem in gratitude to the com- at 9:00 am In Freedman Hall. munity and in honor of a positive reconstruction spirit. Seudah Shlishit 3 Part Mini Series Shabbat Kiddush next week: Join us on Shabbat afternoon as members of our community share their Sponsorship is greatly appreciated. expertise with us on issues related to Torah, Israel, Community and more. Seudah Shlishit in Freedman Hall. First Series: Dates: Nov. -

Message from Rabbi Cohen in This Issue

S I VA N - E L U L 5 7 7 4 • S U M M E R E D I T I O N • J U N E - A U G U S T 2 0 1 4 C O N G R E CG A T I OhN BaE T iH -I S lR iA EgL • BhE R KtE s L E Y MESSAGE FROM RABBI COHEN Sadly, this summer all of our rejoicings are deeply disturbed learning and personal growth. The list I compiled spans several by heartbreaking events in Israel. The biblical poet somberly genres and themes, with a little something for everyone. I highly cries, If I forget thee, oh Jerusalem! Certainly, this summer, wher - encourage us to order these books through our local Judaica ever we may be, at work or on break, our hearts and minds book store, Afikomen. must be intently focused on Jerusalem, on Zion, as an entire For those interested in literary readings of biblical texts, I rec - nation mourns three of its boys. As the days of mourning turn ommend R. Nathaniel Helfgot’s Mikra & Meaning . R. Helgot, into weeks, let us hold on to the urgency of this hour and the my former Tanach rebbe at Yeshivat Chovevei Torah , is a master - profound lessons of unity that emerged out of this horrific ful teacher and writer. His work contains several articles about tragedy. At CBI, we will use the summer days as an opportu - the book of Numbers (particularly relevant to our current Torah nity to delve more deeply into the Torah, and as we do so, I portions) alongside other major biblical texts and reflective works hope that we will keep our nation’s boys, z”l, as a primary focus on biblical scholarship and Modern Orthodoxy. -

Competition February 24Th

February 16, 1973 Volume XLI Number 12 Adar I 14, 5733 Three Ramaz Seniors FOR YOUR ATTENTION AND ACTION Declared Finalists in National Merit Last week's New York Times carried an extraordinary development in the Competition struggle for freedom for Soviet Jewry. I refer to the unprecedented support for that struggle from the Chairman of the Flouse Ways and Means Committee, We are proud to announce to the Representative Wilbur Mills. Kehilath Jeshurun family that three seniors in the current graduating class Mr. Mills gave his unqualified support to the so-called Vanik Bill, which was of the Ramaz Upper School have just introduced in the House of Representatives by Charles A. Vanik (D-Ohio) as a been notified of their position as counterpart to the well known Jackson Amendment introduced in the last session Finalists in the National Merit Com¬ in the Senate. The Vanik Bill would withhold "Most Favored Nation" status from petition. They are: Ron Cohen, Samuel countries who violate international standards, specifically including the Gamoran, and Laura Shragowitz. Five charging of exorbitant exit fees for citizens who wish to seniors had originally placed as semi- emigrate. The Bill would also finalists. These three remain in the withhold loans, grants and credits from those nations which perpetrate such competition in this august position. violations. The National Merit Competition in¬ The Vanik Bill is the key pressure point for American Jewry through which cludes all seniors throughout the coun¬ we can gain repeal or weakening of the ransom tax which is now being charged try. Each finalist is one out of 14,500 to all educated Soviet Jews who wish to students. -

Guide to Erev Pesach on Shabbat 5781 ~ 2021

Guide to Erev Pesach on Shabbat 5781 ~ 2021 This year, 5781/2021, Pesach begins on Saturday night. With Erev Pesach falling on Shabbat, we will have some more pre-Pesach planning than usual. I hope you will find these guidelines helpful. Please let me know if you have any questions. ~ Rabbi Ken Brodkin Question 1: When do we search for Chametz? This year, we search for Chametz on Thursday night, March 25, after 8:15 pm. Before searching, we recite the Bracha of "Al Biur Chometz". Following the search, we say the paragraph of "Kol Chamira". Both these sections may be found in the Artscroll Siddur (Nusach Sephard) on pg. 700. The blessing marks the beginning of our destruction of Chametz; the "Kol Chamira" paragraph (the first of the two printed in the Siddur) annuls our ownership of any Chametz which has escaped our notice. Question 2: When do we burn our Chometz? So as not to create any confusion, we burn our Chametz on Friday, March 26, at the normal time that we would on a regular Erev Pesach—before 12:10 pm. We do not recite any blessing or “Kol Chamira” at that time. Question 3: When do we recite "Kol Chamira" annulling our ownership of Chametz? We do not recite the second "Kol Chamira" when burning our Chametz on Friday. We recite the first "Kol Chamira" when we search for Chametz on Thursday night. We recite the second “Kol Chamira” on Shabbat morning, before 12:10 pm, on pg. 700. Question 4: When do the first-born sons fast? This year, the fast is observed on Thursday, March 25. -

March/April 2020

A Traditional, Egalitarian and Participatory Conservative Synagogue ADAR/NISSAN/IYAR 5780 NEWSLETTER/VOLUME 32:4 MARCH/APRIL 2020 Scholarly Shabbaton: Navigating Jewishness in Christian Worlds with Professors Jessica Cooperman and Hartley Lachter Friday, March 27 and Saturday, 28 wo sustaining pillars of Or Zarua were still seen as suspicious, foreign faiths have been our weekly Shabbat at odds with American values. When the Scholarly Shabbaton services and varied adult education US War Department began preparations to programs. On Friday evening and send American soldiers and sailors to fight Professors Saturday, March 27-28, those two in World War I, it had no plans to introduce Timportant facets of the unique Or Zarua the country to new ideas about religious Jessica Cooperman & experience will coincide. We will convene pluralism. Over the course of the war, as a community for what promises to be however, the American military adopted new Hartley Lachter a wonderful Scholarly Shabbaton, led by policies and practices intended to elevate Friday, March 27 (married) professors Jessica Cooperman the moral character and civic consciousness 6:00 pm Minhah/Kabbalat Shabbat and Hartley Lachter, that will be filled with of its troops. Thanks to the work of the 7:00 pm Dinner (RSVP) stimulating learning, joyous prayer, and Jewish Welfare Board, these new “soldiers’ 8:15 pm Lecture by Dr. Jessica Cooperman: delicious food. welfare programs” became an unexpected Fighting for Judaism in Coming to us from the beautiful Lehigh gateway for renegotiating portrayals and World War I America Valley, Drs. Cooperman and Lachter will give perceptions of Jews and Judaism within Note that you may attend the lecture several lectures over the course of Shabbat American society. -

Halakhic Guide to Pesach Preparations (When Erev Pesach Falls on Shabbat)

Halakhic Guide to Pesach Preparations (when Erev Pesach falls on Shabbat) When Passover begins on Motzei Shabbat (Saturday night) as it does this year, it impacts how we prepare for the holiday in a number of ways. Those changes are detailed within this guide to preparing for Pesach. Ta`anis Bechoros/Fast of the First Born The fast, which is usually observed by first born sons on Erev Pesach, is pushed back to Thursday when Erev Pesach falls on Shabbat. This year the fast is observed on March 25, from 5:37am and until 7:48pm. Jack Shapiro will be making a siyyum on Zoom at 7:30am to celebrating the completion of a tractate of the Talmud. Use this link to register: www.baisabe.com/form/siyyum. Firstborn sons who attend the Zoom siyyum are exempt from fasting for the rest of the day. Bedikat Chametz/The Search for Chametz Normally we search for chametz the night before Passover. This year, we search our homes for chametz on the evening of Thursday, March 25th with a bracha after 7:58pm. After the search the normal nullification (bittul) is recited. (Koren Nusach Sefard Siddur p. 790). This bittul should be recited in a language you understand, which means even if you normally pray in Hebrew, you should probably recite the English on p. 790, rather than the Aramaic on p. 791. Bi’ur Chametz/Burning of the Chametz We can burn the chametz on Friday, March 26th until 12:10pm. The reason for this custom is so that in future years one does not get confused about the proper time to burn chametz. -

ROSH CHODESH ELUL Parshat Re'eh

Mazal Tov Memorial Kaddish Dedicated Daniel and Amy Delson in Memory of on the forethcoming Bar Mitzvah of their Eugen Gluck a giant with the invincible spirit of a son, Samson. Holocaust survivor who strengthened the Jewish people through Torah, Israel and Tzedakah. Joseph and Lieve Guttmann Generous benefactor of the Rabbi Arthur Schneier on the engagement of their grandson, Park East Day School scholarship fund. Beloved father of our devoted members Sidney (Cheryl) Gabriel Leiser to Avigail Hackel. Gluck, and siblings Rosie (Dr. Mark Friedman), Barbara (Alan Weichselbaum), grandfather of Sisterhood Matthew (Shiri) Gluck, and Michael Gluck. Challah for a sweet New Year! Help Generous benefactor who dedicated his life to the support Sisterhood’s Chesed Committee land and people of Israel. and enjoy honey and the Challah Fairy Kenneth Bialkin Challah. distinguished member, prominent leader of the American Jewish community who was in the To order, please call the Synagogue at forefront of United States - Israel solidarity and 212-737-6900. friendship. Sincere condolences to his beloved wife Ann, his partner in the practice of Book of Remembrance tzedaka, devoted daughters Lisa and Johanna and Remember your loved ones in the Book grandchildren, Gideon and Samuel. of Remembrance for 5780. which is May the family be comforted among the currently being complied. mourners of Zion and Jerusalem. Please contact Toby Einsidler at the Yahrzeits Synagogue or register online. Mrs. Rita Weinick - Husband Mrs. Henrietta Berko - Sister Parshat Re’eh Mr. Stanley Davenport - Grandfather August 30-31, 2019 29-30 Av, 5779 Mrs. Susan Rapoport - Father u These are the animals which you Ms. -

The Shabbat Meals

cŠqa SpiritualitySpirituality at at YourYour FingertipsFingertips Enjoying Shabbat: A Guide To The Shabbat Meals National Jewish Outreach Program 989 Sixth Avenue, 10th Floor, New York, NY 10018 646-871-4444 800-44-HEBRE(W) [email protected] www.njop.org Friday Night Dinner With the arrival of Shabbat on Friday night, tranquility descends. Before the candles are lit, cooking and preparing must be concluded. Friday night services begin in the synagogue and are followed, after returning home, by the singing of Shalom Alechem and Aishet Chayil. As the household gathers around the table, family members are enveloped by tradition, as kiddush (blessing over the wine) and ha’mo’tzee (blessing over the bread) are recited. Then comes the Shabbat meal. The actual fare of Shabbat dinner varies depending on custom and personal taste. Many people prefer to eat their favorite foods, while others elect to serve the traditional Shabbat cuisine. A typical, traditional Shabbat menu includes: Fish Because fish is a reminder of both the creation of life and of the Messianic Age (when it is said that the righteous will feast upon the Leviathan, a giant fish), it has almost always held a special place at the Shabbat table. In the Talmud (Shabbat 118b), fish is specifically listed as a way in which one can show delight in Shabbat. Generally served as an appetizer, fish is never eaten together with meat, and is, in fact, served on separate plates with separate “fish forks,” in light of a Talmudic warning that eating fish and meat together can lead to illness (Pesachim 76b). -

June 29, 2018.Pub

AHAVAS ACHIM NEWSLETTER AHAVAS ACHIM NEWSLETTER י"ז תמוז תשע"ח בלק JUNE 29, 2018 SCHEDULE OF SERVICES SYNAGOGUE NEWS SUMMER SHABBAT AFTERNOON SCHEDULE שבת Beginning next Shabbat, July 7, we will מזל טוב .Friday Candlelighting...........8:13 p.m Friday Mincha/Kabbalat Shabbat/Maariv Mazel Tov to Joe and Rachel David on the begin our summer Shabbat afternoon ..........................7:00 & 8:20 p.m. birth of a son. The Shalom Zachar will be schedule for July and August. There will Shacharit ..................7:00 & 9:00 a.m. held at 103 North 8th Ave. (corner of be two options for Mincha: 5:00 p.m. Pre-Group Babysitting ..........9:00 a.m. Abbott) at 9:30 p.m. and b'zman, approximately 25 minutes Latest Shema........................9:16 a.m. before sunset, varying each week. Mazel Tov to Arthur and Marina Miller on Teen Minyan.........................9:30 a.m. Seudah Shlishit with a guest D'var Torah the birth of a grandson. Mazel Tov to the Youth Groups.....................10:00 a.m. will be after the second Mincha in the parents, Arielle and Zack Goodwin. Baby Group ........................10:30 a.m. Downstairs Social Hall, followed by Maariv. Sponsorships for the Seudah Kiddush is sponsored by the Sisterhood. SHIVA ASAR B'TAMMUZ Shlishit are available for $100, as Daf Yomi (Zevachim 78) ......7:30 p.m. throughout the rest of the year. Please The fast day of Shiva Asar BTammuz, Mincha..................................8:10 p.m. note this change in schedule from commemorating the breaching of the walls of Learning Seudah Shlishit .....8:30 p.m.