Ethical Birding Call Playback and Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elementary School Program

MAST ACADEMY OUTREACH ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PROGRAM Birds of the Everglades Pre-site Package MAST Academy Maritime and Science Technology High School Miami-Dade County Public Schools Miami, Florida 0 Birds of the Everglades Grade 5 Pre-Site Packet Table of Contents Sunshine State Standards FCAT Benchmarks – Grade 5 i Teacher Instructions 1 Destination: Everglades National Park 3 The Birds of Everglades National Park 4 Everglades Birds: Yesterday and Today 6 Birdwatching Equipment Binoculars 7 A Field Guide 7 Field Notes 8 In-Class Activity 13 Online Resources 19 Answer Key 20 Application for Education Fee Waiver 27 1 BIRDS OF THE EVERGLADES SUNSHINE STATE STANDARDS FCAT BENCHMARKS – Grade 5 Science Benchmarks Assessed at Grade 5 Strand F: Processes of Life SC.F.1.2.3 The student knows that living things are different but share similar structures. Strand G: How Living Things Interact with Their Environment SC.G.1.2.2 The student knows that living things compete in a climatic region with other living things and that structural adaptations make them fit for an environment. SC.G1.2.5 The student knows that animals eat plants or other animals to acquire the energy they need for survival. SC.G1.2.7 The student knows that variations in light, water, temperature, and soil content are largely responsible for the existence of different kinds of organisms and population densities in an ecosystem. SC.G.2.2.2 The student knows that the size of a population is dependent upon the available resources within its community. SC.G.2.2.3 The student understands that changes in the habitat of an organism may be beneficial or harmful. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

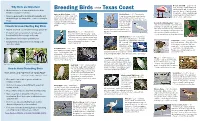

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Birdwatching in Portugal

birdwatchingIN PORTUGAL In this guide, you will find 36 places of interest 03 - for birdwatchers and seven suggestions of itineraries you may wish to follow. 02 Accept the challenge and venture forth around Portugal in search of our birdlife. birdwatching IN PORTUGAL Published by Turismo de Portugal, with technical support from Sociedade Portuguesa para o Estudo das Aves (SPEA) PHOTOGRAPHY Ana Isabel Fagundes © Andy Hay, rspb-images.com Carlos Cabral Faisca Helder Costa Joaquim Teodósio Pedro Monteiro PLGeraldes SPEA/DLeitão Vitor Maia Gerbrand AM Michielsen TEXT Domingos Leitão Alexandra Lopes Ana Isabel Fagundes Cátia Gouveia Carlos Pereira GRP A HIC DESIGN Terradesign Jangada | PLGeraldes 05 - birdwatching 04 Orphean Warbler, Spanish Sparrow). The coastal strip is the preferred place of migration for thousands of birds from dozens of different species. Hundreds of thousands of sea and coastal birds (gannets, shear- waters, sandpipers, plovers and terns), birds of prey (eagles and harriers), small birds (swallows, pipits, warblers, thrushes and shrikes) cross over our territory twice a year, flying between their breeding grounds in Europe and their winter stays in Africa. ortugal is situated in the Mediterranean region, which is one of the world’s most im- In the archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, there p portant areas in terms of biodiversity. Its are important colonies of seabirds, such as the Cory’s landscape is very varied, with mountains and plains, Shearwater, Bulwer’s Petrel and Roseate Tern. There are hidden valleys and meadowland, extensive forests also some endemic species on the islands, such as the and groves, rocky coasts and never-ending beaches Madeiran Storm Petrel, Madeiran Laurel Pigeon, Ma- that stretch into the distance, estuaries, river deltas deiran Firecrest or the Azores Bullfinch. -

Birdwatching Around Corrigin

SITES TO THE WEST INTRODUCTON: In the following woodland sites, look for Australian Agricultural and pastoral industries form the basis of BIRDWATCHING Ringneck, Red-capped Parrot, Rufous Whistler, Grey this thriving community. A visit to some of the places Shrike-thrush, Red-capped Robin, Southern Scrub- mentioned will help you to experience a wide range robin, Redthroat, Weebill, Striated Pardalote and of natural features, vegetation and bird life within the AROUND Brown-headed Honeyeater. shire and surrounding areas. From a bird-watching perspective, this is a good area to see raptors. CORRIGIN Please take care if you need to park on road verges to access 1. KUNJIN sites, especially in summer when the fire risk is greater. An old town site adjoins a nature reserve. Excellent woodlands ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: including Rock Sheoak, Kondinin Blackbutt and mallees. Illustrations: Judy Blyth, Alan Collins,, Keith Lightbody, Ron Johnstone, Susan Tingay, Eric Tan. Striated Pardalote Local information: Robin Campbell, BirdLife Avon & Birdata, 2. JUBUK NORTH ROAD Wendy Kenworthy. 20km west of Corrigin. Parkland with patches of York Gum woodland, heath and salt-land. Local contacts: Robin 0499 624 038 Lawry 0429 164 187 3. LOMOS Guide No. 20AB; Revised Nov 2017. All content is subject to A good patch of mixed open woodland. Red Morrells, copyright ©. Queries to BirdLife Western Australia. Silver Mallet, mallees and Wandoo support Rufous Treecreeper, Redthroat, Crimson Chat, Varied Sittella and Grey Currawong. 4. OVERHEU Rufous Whistler On Brookton Hwy, with Eucalyptus macrocarpa and sheoak. Best access is from a roadside bay on Brookton Nankeen Kestrel by David Free Highway. BirdLife Western Australia members are offered a variety of 5. -

Birdwatching in the Mamirauá Lake As an Appeal to Ecotourists/Birdwatchers

BIRDWATCHING IN THE MAMIRAUÁ LAKE AS AN APPEAL TO ECOTOURISTS/BIRDWATCHERS. OBSERVAÇÃO DE AVES NO LAGO MAMIRAUÁ COMO ATRATIVO PARA ECOTURISTAS/BIRDWATCHERS. Bianca Bernardon1 Pedro Meloni Nassar2 1 Grupo de Pesquisa em Ecologia de Vertebrados Terrestres, Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Mestrado Profissionalizante em Gestão de Áreas Protegidas, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia. KEY WORDS: ABSTRACT Sustainable Development The Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve fits the profile of a good destination for Reserve; birdwatching, because it has high species diversity, bilingual guides, updated bird lists, field guides and adequate infrastructure. In this paper we present the bird species observed during a Uakari Lodge; regular type of tourist activity held in Uakari Lodge and also relate the richness and diversity of Amazon; birds to fluctuations in water level during several months. The study was conducted between June 2009 and September 2011, and it took a total of 68 boat trips, 480 ecotourists, adding Varzea Forest. up to a total of 238 hours. 134 bird species were recorded, which corresponds to 37% of the number of species that occurs in the Mamirauá SDR. Large-billed Tern (Phaetusa simplex) and Striated Heron (Butorides striata) were seen at all the trips. Yellow-rumped Cacique (Cacicus cela) and Black-collared Hawk (Busarellus nigricolis) were observed 62 times. Horned Screamer (Anhima cornuta) and Hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin) came right after, with 61 sightings. The distribution of observations of attractive species really provide the more informed ecotourist some real entertainment, as to which would be the best time of year to visit the Mamirauá SDR. -

The Status and Distribution of European Storm-Petrels Hydrobates Pelagicus and Manx Shearwaters Puffinus Puffinus on the Isles of Scilly

2002 Storm-petrels andManx Sheam aters onScilly 1 The Status and distribution of European Storm-petrels Hydrobates pelagicus and Manx Shearwaters Puffinus puffinus on the Isles of Scilly 1*, 3 4 5 V. Heaney N. Ratcliffe A. Brown P.J. Robinson & L. Lock 1, , Heaney V., Ratcliffe N., Brown A., Robinson P & Lock L. 2002. The status and distribution of European Storm-petrels Hydrobatespelagicus and Manx Shearwaters Puffinuspuffinus Seabirds This describes the on the Isles of Scilly. Atlantic 4(1): 1-16. paper first the distribution and abundance Storm- comprehensive survey of ofbreeding European Manx petrels and Shearwaters on the Isles ofScilly. Diurnal tapeplayback ofvocalisations in was used to survey those islands the archipelago on which birds had previously been reportedbreedingand to search others with suitable habitat. The total breedingpopulation ofStorm-petrels was 1475 Apparently Occupied Sites and of Manx Sheanvaters 201 Apparently OccupiedBurrows. These numbers are ofregionalimportancefor both species and the numbers of Storm-petrels are internationally important. Storm-petrel breeding distribution was restricted to rat-free outer islands, but some Manx Shearwater colonies werefoundon islands with rats and alsoferal cats. The role oferadication and control of mammalian predators in the conservation ofpetrels on the ScillyIsles is discussed. 'The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, England, U.K.; "English Nature, Northminster House, Northminster Road, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire PEI 1UA, England, U.K.; ’Riviera House, Parade, St. Mary’s, Isles of 4 Scilly TR21 OLP, England, LUC.; The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Keble House, Southemhay Gardens, Exeter, Devon EX1 1NT, England, UK. -

Bahamasyou’Ve Heard of Our White Sand Beaches

DISCOVER THE BIRDS OF THE BahamasYou’ve heard of our white sand beaches. Our turquoise ocean waters. But what about our spectacular birds found nowhere else in the world? The Bahamas is a sublime spot for birdwatching the whole family will love. Beauty on a wing. The vibrant birds of The Bahamas will delight you. Search for over 300 species - including 6 species found only here - in landscapes of jaw-dropping natural beauty. Ocean adventures. Take a break from watching our colorful winged residents to watch our colorful aquatic ones. Grab a mask and explore coral reefs in some of the clearest waters in the world. Or use a rod and fly to find silvery bonefish in the turquoise blue. A chance to chill. After your outdoor exploration it’s time to put your feet up and relax. And there’s no better place to sip some sunshine and let the worries of the world fall away. Pack a beach umbrella and find your slice of heaven. Fun for the whole brood. Your choice for travel needs to bring smiles to the entire family. Luckily there’s something for everyone in The Bahamas Bring your brood to explore our islands and you won’t disappoint. Maximize your birding experience with an Audubon- trained guide. Want to see more of The Bahamas’ famed birds? Embark on your adventure with a local bird guide. Trained by Bahamas National Trust & Audubon experts, our bird guides have intimate knowledge of local birds and the best locations for spotting them. Hiring a guide also helps strengthen the local eco-economy, improving livelihoods while providing incentives for communities to protect important Cuban Emerald bird habitat. -

The Big Year: a Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession Kindle Edition the Big Year (The Movie)

The Big Year, the book and movie about the 365 day marathon of birdwatching, to find and identify an extraordinary 745 different species of birds by official year-end count. http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0036QVOHS/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?ie=UTF8&btkr=1 The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature, and Fowl Obsession Kindle Edition Every year on January 1, a quirky crowd of adventurers storms out across North America for a spectacularly competitive event called a Big Year -- a grand, grueling, expensive, and occasionally vicious, "extreme" 365-day marathon of birdwatching. For three men in particular, 1998 would be a whirlwind, a winner-takes-nothing battle for a new North American birding record. In frenetic pilgrimages for once-in-a-lifetime rarities that can make or break their lead, the birders race each other from Del Rio, Texas, in search of the rufous-capped warbler, to Gibsons, British Columbia, on a quest for Xantus's hummingbird, to Cape May, New Jersey, seeking the offshore great skua. Bouncing from coast to coast on their potholed road to glory, they brave broiling deserts, roiling oceans, bug-infested swamps, a charge by a disgruntled mountain lion, and some of the lumpiest motel mattresses known to man. The unprecedented year of beat-the-clock adventures ultimately leads one man to a new record -- one so gigantic that it is unlikely ever to be bested...finding and identifying an extraordinary 745 different species by official year-end count. Prize-winning journalist Mark Obmascik creates a rollicking, dazzling narrative of the 275,000-mile odyssey of these three obsessives as they fight to the finish to claim the title in the greatest -- or maybe the worst -- birding contest of all time. -

Museum Birdwatching

Museum Birds of a feather flock together—in the galleries of the DMA! Explore our feathered friends in works of art and match them to their real-life inspiration. Birdwatching Find fun facts and check your answers on the back. 1 2 How is this bird holding its wings? Which way is it holding its head? Act it out! Can you count the number of 3 colors the artist used in this If we could unfreeze the scene of this picture? Do you think this bird is painting, what do you think would painted exactly as the artist saw happen next? What would the bird do? it? What did the artist change? What would the dog do? 4 How many birds can you 5 find in this painting? What do you think might have been This type of bird mates stored in this little pot? Notice its for life and is frequently spout—a good clue that it could have used as symbol for peace been used for liquid. or love. The real-life version of this bird is far more colorful, but ceramics from Peru at this time were traditionally painted using only red and white, no matter the color of their subject. Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Water Spaniel Confronting a Heron, 1722, oil on canvas, Lent by the Michael L. Rosenberg Foundation, 32.2019.9; Detail view: Mantle with Condors, Paracas culture, c. 300-100 B.C., Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., in memory of John O’Boyle, 1972.4.McD; Three Owls (detail), Otis Dozier, 1957, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of The Dozier Foundation, 1990.86; Spout-and-bridge bottle: bird form, Moche, 100–350 CE, Dallas Museum of Art, The Nora and John Wise Collection, gift of Mr. -

Seabird Data for Describing Marine Conservation Areas

Seabird Data for Describing Marine Conservation Areas In 2008, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 9th Conference RESEARCH SUMMARY of the Parties approved a set of criteria for identifying Ecologically or April 2012 Biologically Significant Areas (EBSAs), a crucial step in protecting marine habitats and biodiversity. A series of regional workshops began in 2011 BirdLife International’s Marine to describe areas that meet these EBSA criteria. Important Bird Areas toolkit is a summary of the experiences from 40 Seabird data are especially useful in such conservation planning countries in the BirdLife Partnership. exercises. BirdLife International has been compiling and analysing seabird data to identify Important Bird Areas (IBAs), a process Study citation: BirdLife International (2010). explained in BirdLife’s Marine IBA Toolkit. This has allowed lists of IBAs Marine Important Bird Areas toolkit: standardised techniques for identifying priority to be provided to EBSA regional workshops, and these have proved sites for the conservation of seabirds at sea. to be a vital contribution to describing EBSAs. BirdLife International, Cambridge UK. Version 1.2: February 2011. www.birdlife.org/eu/pdfs/ The IBA process is effective for the following reasons: Marinetoolkitnew.pdf www.BirdLife.org • Birds are indicators of diversity and ecosystems along migration routes. productivity: The presence of diverse Seabird tracking data can be used to and abundant seabirds is a strong assess connectivity between sites. indicator of the presence of other • Seabirds are widely represented across taxa, such as the seabirds’ prey and ecosystems: The global distribution other top predators that compete of seabirds makes them very useful for them. -

AUSTRALIAN AVICULTURE VOLUME 71 - No

AUSTRALIAN AVICULTURE VOLUME 71 - No. 1 January 2017 THE AVICULTURAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA INC. DIRECTORY Members are requested to direct communications to the following officers Make sure your name and address are easy to read PRESIDENT Lou Dall’Est, PO Box 405, Kilmore, Victoria 3764. Phone [03] 5782 0023 VICE PRESIDENT Matt Baird Phone 0418 323 487 Email [email protected] SECRETARY Graeme Hocking 125-129 North Mountain Road, Heathcote Junction, Victoria 3758 Phone [03] 5787 1292 – Email: [email protected] [General Enquiries – General Correspondence] ASSISTANT SECRETARY/ LOST OR FOUND BIRDS Tom Hobbs, PO Box 236, Melton, Victoria 3337. Phone: [03] 9743 6960 Email: [email protected] TREASURER/PHOTO COMP CO-CORDINATOR Warwick Remington 3 Rumler Crt Ballarat Victoria 3350 Phone 0407 348 203 Email: [email protected] MEMBERSHIP REGISTRAR/ SERVICE ITEMS STEWARD Stephanie Gough 52 One Tree Hill Road, Ferny Creek, Victoria 3786 Phone [03] 9755 2935 – Email: [email protected] [Applications for Membership – Renewal Memberships – Non-Receipt of Australian Aviculture] SERVICE ITEMS STEWARD John Pope, 58 Forest Park Road Upwey Phone [03] 9754 1151 or 0419 691 869 Email: [email protected] MONTHLY MEETING PROGRAM CO-ORDINATOR Barrie Wicks Phone 9735 5462, or 0407 865 779, Email [email protected] COMMITTEE Stephan Maric, Charlie Mizzi, Mark Reynolds, Gina Wilson STOLEN BIRD HOTLINE David Renshaw, Phone 0428 518 646 EDITOR Colin Riddiford, 14 Huxley Avenue, North Dandenong, Victoria 3175. Phone (03) 9795 2981 or 0418 420 164 Email…[email protected] [ Members’ Notices - Birds for sale/wanted to buy - Articles – Display Advertisements ] COVER PHOTOS Front:- Red-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus cafer) © Peter Booth - from the 2016 Photo Comp Back Cover:- Red Backed Kingfisher (Todiramphus pyrrhopygius) © Ian Davies - from the 2016 Photo Comp Inside Back Cover:- Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) © John Stephens - from the 2016 Photo Comp AUSTRALIAN AVICULTURE JOURNAL OF THE AVICULTURAL SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA INCORPORATED Registration No.