Bird Language Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elementary School Program

MAST ACADEMY OUTREACH ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PROGRAM Birds of the Everglades Pre-site Package MAST Academy Maritime and Science Technology High School Miami-Dade County Public Schools Miami, Florida 0 Birds of the Everglades Grade 5 Pre-Site Packet Table of Contents Sunshine State Standards FCAT Benchmarks – Grade 5 i Teacher Instructions 1 Destination: Everglades National Park 3 The Birds of Everglades National Park 4 Everglades Birds: Yesterday and Today 6 Birdwatching Equipment Binoculars 7 A Field Guide 7 Field Notes 8 In-Class Activity 13 Online Resources 19 Answer Key 20 Application for Education Fee Waiver 27 1 BIRDS OF THE EVERGLADES SUNSHINE STATE STANDARDS FCAT BENCHMARKS – Grade 5 Science Benchmarks Assessed at Grade 5 Strand F: Processes of Life SC.F.1.2.3 The student knows that living things are different but share similar structures. Strand G: How Living Things Interact with Their Environment SC.G.1.2.2 The student knows that living things compete in a climatic region with other living things and that structural adaptations make them fit for an environment. SC.G1.2.5 The student knows that animals eat plants or other animals to acquire the energy they need for survival. SC.G1.2.7 The student knows that variations in light, water, temperature, and soil content are largely responsible for the existence of different kinds of organisms and population densities in an ecosystem. SC.G.2.2.2 The student knows that the size of a population is dependent upon the available resources within its community. SC.G.2.2.3 The student understands that changes in the habitat of an organism may be beneficial or harmful. -

A Thesis Entitled Nocturnal Bird Call Recognition System for Wind Farm

A Thesis entitled Nocturnal Bird Call Recognition System for Wind Farm Applications by Selin A. Bastas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Electrical Engineering _______________________________________ Dr. Mohsin M. Jamali, Committee Chair _______________________________________ Dr. Junghwan Kim, Committee Member _______________________________________ Dr. Sonmez Sahutoglu, Committee Member _______________________________________ Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2011 Copyright 2011, Selin A. Bastas. This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Nocturnal Bird Call Recognition System for Wind Farm Applications by Selin A. Bastas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Electrical Engineering The University of Toledo December 2011 Interaction of birds with wind turbines has become an important public policy issue. Acoustic monitoring of birds in the vicinity of wind turbines can address this important public policy issue. The identification of nocturnal bird flight calls is also important for various applications such as ornithological studies and acoustic monitoring to prevent the negative effects of wind farms, human made structures and devices on birds. Wind turbines may have negative impact on bird population. Therefore, the development of an acoustic monitoring system is critical for the study of bird behavior. This work can be employed by wildlife biologist for developing mitigation techniques for both on- shore/off-shore wind farm applications and to address bird strike issues at airports. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

The Kavirondo Escarpment: a Previously Unrecognized Site of High Conservation Value in Western Kenya

Scopus 33: 64-69 January 2014 The Kavirondo Escarpment: a previously unrecognized site of high conservation value in Western Kenya James Bradley and David Bradley Summary In western Kenya, extant woodland habitats and their representative bird species are increasingly scarce outside of protected areas. With the assistance of satellite imagery we located several minimally impacted ecosystems on the Kavirondo Escarpment (0°1.7’ S, 34°56.5’ E), which we then visited to examine the vegetation communities and investigate the avifauna. Despite only a limited effort there, we report several new atlas square occurrences, presence of the local and poorly known Rock Cisticola Cisticola emini and a significant range extension for the Stone Partridge Ptilopachus petrosus. Our short visits indicate high avian species richness is associated with the escarpment and we suggest comprehensive biodiversity surveys here are warranted. Introduction The Kavirondo Escarpment in central-west Kenya is a significant geologic and topographic feature. It straddles the equator, extending over 45 km from east to west, and comprises the northern fault line escarpment of the Kavirondo Rift Valley (Baker et al. 1972). Immediately to the south lie the lowlands of the Lake Victoria Basin and Nyando River Valley, and to the north, the high plateau of the western Kenya highlands (Fig. 1). The escarpment slopes range in elevation from 1200–1700 m at the western end to 1500–2000 m in the east, where it gradually merges with the Nandi Hills. Numerous permanent and seasonal drainages on the escarpment greatly increase the extent of land surface and variation in slope gradients, as well as the richness of vegetation communities. -

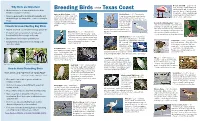

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Directional Embedding Based Semi-Supervised Framework for Bird Vocalization Segmentation ⇑ Anshul Thakur , Padmanabhan Rajan

Applied Acoustics 151 (2019) 73–86 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Applied Acoustics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/apacoust Directional embedding based semi-supervised framework for bird vocalization segmentation ⇑ Anshul Thakur , Padmanabhan Rajan School of Computing and Electrical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, Himachal Pradesh, India article info abstract Article history: This paper proposes a data-efficient, semi-supervised, two-pass framework for segmenting bird vocaliza- Received 16 October 2018 tions. The framework utilizes a binary classification model to categorize frames of an input audio record- Accepted 23 February 2019 ing into the background or bird vocalization. The first pass of the framework automatically generates training labels from the input recording itself, while model training and classification is done during the second pass. The proposed framework utilizes a reference directional model for obtaining a feature Keywords: representation called directional embeddings (DE). This reference directional model acts as an acoustic Bird vocalization segmentation model for bird vocalizations and is obtained using the mixtures of Von-Mises Fisher distribution Bioacoustics (moVMF). The proposed DE space only contains information about bird vocalizations, while no informa- Directional embedding tion about the background disturbances is reflected. The framework employs supervised information only for obtaining the reference directional model and avoids the background modeling. Hence, it can be regarded as semi-supervised in nature. The proposed framework is tested on approximately 79,000 vocalizations of seven different bird species. The performance of the framework is also analyzed in the presence of noise at different SNRs. Experimental results convey that the proposed framework performs better than the existing bird vocalization segmentation methods. -

Birdwatching in Portugal

birdwatchingIN PORTUGAL In this guide, you will find 36 places of interest 03 - for birdwatchers and seven suggestions of itineraries you may wish to follow. 02 Accept the challenge and venture forth around Portugal in search of our birdlife. birdwatching IN PORTUGAL Published by Turismo de Portugal, with technical support from Sociedade Portuguesa para o Estudo das Aves (SPEA) PHOTOGRAPHY Ana Isabel Fagundes © Andy Hay, rspb-images.com Carlos Cabral Faisca Helder Costa Joaquim Teodósio Pedro Monteiro PLGeraldes SPEA/DLeitão Vitor Maia Gerbrand AM Michielsen TEXT Domingos Leitão Alexandra Lopes Ana Isabel Fagundes Cátia Gouveia Carlos Pereira GRP A HIC DESIGN Terradesign Jangada | PLGeraldes 05 - birdwatching 04 Orphean Warbler, Spanish Sparrow). The coastal strip is the preferred place of migration for thousands of birds from dozens of different species. Hundreds of thousands of sea and coastal birds (gannets, shear- waters, sandpipers, plovers and terns), birds of prey (eagles and harriers), small birds (swallows, pipits, warblers, thrushes and shrikes) cross over our territory twice a year, flying between their breeding grounds in Europe and their winter stays in Africa. ortugal is situated in the Mediterranean region, which is one of the world’s most im- In the archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, there p portant areas in terms of biodiversity. Its are important colonies of seabirds, such as the Cory’s landscape is very varied, with mountains and plains, Shearwater, Bulwer’s Petrel and Roseate Tern. There are hidden valleys and meadowland, extensive forests also some endemic species on the islands, such as the and groves, rocky coasts and never-ending beaches Madeiran Storm Petrel, Madeiran Laurel Pigeon, Ma- that stretch into the distance, estuaries, river deltas deiran Firecrest or the Azores Bullfinch. -

Vocal Communication in Zebra Finches: a Focused Description of Pair Vocal Activity

Vocal communication in zebra finches: a focused description of pair vocal activity Dissertation Fakultät für Biologie Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München durchgeführt am Max-Planck-Institut für Ornithologie Seewiesen vorgelegt von Pietro Bruno D’Amelio München, 2018 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Manfred Gahr Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Niels Dingemanse Eingereicht am: 06.03.2018 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 08.05.2018 Diese Dissertation wurde unter der Leitung von Prof. Dr. Manfred Gahr und Dr. Andries ter Maat angefertigt. i ii Table of Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... iv General Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Vocal communication ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodological challenges and how they were approached .................................................................... 8 Vocal individual recognition ................................................................................................................... 10 Pair communication ................................................................................................................................ 11 References .................................................................................................................................................. -

Songs of the Wild: Temporal and Geographical Distinctions in the Acoustic Properties of the Songs of the Yellow-Breasted Chat

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses and Dissertations in Animal Science Animal Science Department 12-3-2007 Songs of the Wild: Temporal and Geographical Distinctions in the Acoustic Properties of the Songs of the Yellow-Breasted Chat Jackie L. Canterbury University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/animalscidiss Part of the Animal Sciences Commons Canterbury, Jackie L., "Songs of the Wild: Temporal and Geographical Distinctions in the Acoustic Properties of the Songs of the Yellow-Breasted Chat" (2007). Theses and Dissertations in Animal Science. 4. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/animalscidiss/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Animal Science Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations in Animal Science by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SONGS OF THE WILD: TEMPORAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DISTINCTIONS IN THE ACOUSTIC PROPERTIES OF THE SONGS OF THE YELLOW-BREASTED CHAT by Jacqueline Lee Canterbury A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Animal Science Under the Supervision of Professors Dr. Mary M. Beck and Dr. Sheila E. Scheideler Lincoln, Nebraska November, 2007 SONGS OF THE WILD: TEMPORAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DISTINCTIONS IN ACOUSTIC PROPERTIES OF SONG IN THE YELLOW-BREASTED CHAT Jacqueline Lee Canterbury, PhD. University of Nebraska, 2007 Advisors: Mary M. Beck and Sheila E. Scheideler The Yellow-breasted Chat, Icteria virens, is a member of the wood-warbler family, Parulidae, and exists as eastern I. -

Evidence for Human-Like Conversational Strategies in An

EVIDENCE FOR HUMAN-LIKE CONVERSATIONAL STRATEGIES IN AN AFRICAN GREY PARROT'S SPEECH by ERIN NATANNIE COLBERT-WHITE (Under the Direction of Dorothy Fragaszy) ABSTRACT Researchers have established many similarities in the structure and function of human and avian communication systems. This dissertation investigated one unique nonhuman communication system—that of a speech-using African Grey parrot. In the same way that humans learn communicative competence (i.e., knowing what to say and how given a particular social context), I hypothesized that Cosmo the parrot‘s vocalizations to her caregiver, BJ, would show evidence of similar learning. The first study assessed turn-taking and the thematic nature of Cosmo‘s conversations with BJ. Results confirmed that Cosmo took turns during conversations which were very similar to humans‘ average turn-taking time. She also maintained thematically linked dialogues, indicating strategic use of her vocal units. The second study investigated Cosmo‘s ability to take BJ‘s auditory perspective by manipulating the distance between the two speakers. As predicted, Cosmo vocalized significantly more loudly when her owner was out of the room, and those vocalizations classified as social (e.g., kiss sounds) were uttered significantly more loudly than vocalizations which were considered nonsocial (e.g., answering machine beep sounds). These results suggested Cosmo may be able to take the perspective of a social partner, an ability others have documented in Greys using alternative tasks. Strategic use of vocalizations was revisited in Studies 3 and 4. The third study examined Cosmo‘s requesting behavior by comparing three separate corpora (i.e., bodies of text): Cosmo‘s normal vocalizations to BJ without requesting, Cosmo‘s vocalizations following a denied request, and Cosmo‘s vocalizations following an ignored request. -

Birdwatching Around Corrigin

SITES TO THE WEST INTRODUCTON: In the following woodland sites, look for Australian Agricultural and pastoral industries form the basis of BIRDWATCHING Ringneck, Red-capped Parrot, Rufous Whistler, Grey this thriving community. A visit to some of the places Shrike-thrush, Red-capped Robin, Southern Scrub- mentioned will help you to experience a wide range robin, Redthroat, Weebill, Striated Pardalote and of natural features, vegetation and bird life within the AROUND Brown-headed Honeyeater. shire and surrounding areas. From a bird-watching perspective, this is a good area to see raptors. CORRIGIN Please take care if you need to park on road verges to access 1. KUNJIN sites, especially in summer when the fire risk is greater. An old town site adjoins a nature reserve. Excellent woodlands ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: including Rock Sheoak, Kondinin Blackbutt and mallees. Illustrations: Judy Blyth, Alan Collins,, Keith Lightbody, Ron Johnstone, Susan Tingay, Eric Tan. Striated Pardalote Local information: Robin Campbell, BirdLife Avon & Birdata, 2. JUBUK NORTH ROAD Wendy Kenworthy. 20km west of Corrigin. Parkland with patches of York Gum woodland, heath and salt-land. Local contacts: Robin 0499 624 038 Lawry 0429 164 187 3. LOMOS Guide No. 20AB; Revised Nov 2017. All content is subject to A good patch of mixed open woodland. Red Morrells, copyright ©. Queries to BirdLife Western Australia. Silver Mallet, mallees and Wandoo support Rufous Treecreeper, Redthroat, Crimson Chat, Varied Sittella and Grey Currawong. 4. OVERHEU Rufous Whistler On Brookton Hwy, with Eucalyptus macrocarpa and sheoak. Best access is from a roadside bay on Brookton Nankeen Kestrel by David Free Highway. BirdLife Western Australia members are offered a variety of 5. -

Birdwatching in the Mamirauá Lake As an Appeal to Ecotourists/Birdwatchers

BIRDWATCHING IN THE MAMIRAUÁ LAKE AS AN APPEAL TO ECOTOURISTS/BIRDWATCHERS. OBSERVAÇÃO DE AVES NO LAGO MAMIRAUÁ COMO ATRATIVO PARA ECOTURISTAS/BIRDWATCHERS. Bianca Bernardon1 Pedro Meloni Nassar2 1 Grupo de Pesquisa em Ecologia de Vertebrados Terrestres, Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Mestrado Profissionalizante em Gestão de Áreas Protegidas, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia. KEY WORDS: ABSTRACT Sustainable Development The Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve fits the profile of a good destination for Reserve; birdwatching, because it has high species diversity, bilingual guides, updated bird lists, field guides and adequate infrastructure. In this paper we present the bird species observed during a Uakari Lodge; regular type of tourist activity held in Uakari Lodge and also relate the richness and diversity of Amazon; birds to fluctuations in water level during several months. The study was conducted between June 2009 and September 2011, and it took a total of 68 boat trips, 480 ecotourists, adding Varzea Forest. up to a total of 238 hours. 134 bird species were recorded, which corresponds to 37% of the number of species that occurs in the Mamirauá SDR. Large-billed Tern (Phaetusa simplex) and Striated Heron (Butorides striata) were seen at all the trips. Yellow-rumped Cacique (Cacicus cela) and Black-collared Hawk (Busarellus nigricolis) were observed 62 times. Horned Screamer (Anhima cornuta) and Hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin) came right after, with 61 sightings. The distribution of observations of attractive species really provide the more informed ecotourist some real entertainment, as to which would be the best time of year to visit the Mamirauá SDR.