Forthcoming MHS Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

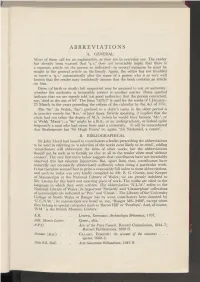

ABBREVIATIONS Use. the Reader That

ABBREVIATIONS A. GENERAL Most of these call for no explanation, as they are in everyday use. The reader has already been warned that 'q.v.' does not invariably imply that there is a separate article on the person so indicated—in several instances he must be sought in the general article on his family. Again, the editor has not troubled to insert a 'q.v.' automatically after the name of a person who is so very well known that the reader may confidently assume that the book contains an article on him. Dates (of birth or death) left unqueried may be assumed to rest on authority: whether the authority is invariably correct is another matter. Dates queried indicate that we are merely told (on good authority) that the person concerned, say, 'died at the age of 64'. The form '1676/7' is used for the weeks of 1 January- 25 March in the years preceding the reform of the calendar by the Act of 1751. The 'Sir' (in Welsh, 'Syr') prefixed to a cleric's name in the older period is in practice merely the 'Rev.' of later times. Strictly speaking, it implied that the cleric had not taken the degree of M.A. (when he would have become 'Mr.', or in Welsh 'Mastr'); a 'Sir' might be a B.A., or an undergraduate, or indeed quite frequently a man who had never been near a university. It will be remembered that Shakespeare has 'Sir Hugh Evans' or, again, 'Sir Nathaniel, a curate'. B. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL Sir John Lloyd had issued to contributors a leaflet prescribing the abbreviations to be used in referring to 'a selection of the works most likely to be cited', adding 'contributors will abbreviate the titles of other works, but the abbreviations should not be such as to furnish no clue at all to the reader when read without context'. -

HAY-ON-WYE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Review May 2016

HAY-ON-WYE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Review May 2016 BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK Contents 1. Introduction 2. The Planning Policy Context 3. Location and Context 4. General Character and Plan Form 5. Landscape Setting 6. Historic Development and Archaeology 7. Spatial Analysis 8. Character Analysis 9. Definition of Special Interest of the Conservation Area 10. The Conservation Area Boundary 11. Summary of Issues 12. Community Involvement 13. Local Guidance and Management Proposals 14. Contact Details 15. Bibliography Review May 2016 1. Introduction Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 imposes a duty on Local Planning Authorities to determine from time to time which parts of their area are „areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance‟ and to designate these areas as conservation areas. Hay-on-Wye is one of four designated conservation areas in the National Park. Planning authorities have a duty to protect these areas from development which would harm their special historic or architectural character and this is reflected in the policies contained in the National Park’s Local Development Plan. There is also a duty to review Conservation Areas to establish whether the boundaries need amendment and to identify potential measures for enhancing and protecting the Conservation Area. The purpose of a conservation area appraisal is to define the qualities of the area that make it worthy of conservation area status. A clear, comprehensive appraisal of its character provides a sound basis for development control decisions and for developing initiatives to improve the area. -

Copies of Presteigne Parish Registers, Radnorshire

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Copies of Presteigne parish registers, Radnorshire. (NLW Films 1060-2) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 12, 2017 Printed: May 12, 2017 https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/copies-of-presteigne-parish-registers- radnorshire archives.library .wales/index.php/copies-of-presteigne-parish-registers-radnorshire Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Copies of Presteigne parish registers, Radnorshire. Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 3 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 4 - Tudalen | Page 2 - NLW Films 1060-2 Copies of Presteigne parish registers, Radnorshire. Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information Lleoliad | Repository: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Teitl -

English Heritage Og Middelalderborgen

English Heritage og Middelalderborgen http://blog.english-heritage.org.uk/the-great-siege-of-dover-castle-1216/ Rasmus Frilund Torpe Studienr. 20103587 Aalborg Universitet Dato: 14. september 2018 Indholdsfortegnelse Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 Indledning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Problemstilling ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kulturarvsdiskussion ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Diskussion om kulturarv i England fra 1980’erne og frem ..................................................................... 5 Definition af Kulturarv ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hvordan har kulturarvsbegrebet udviklet sig siden 1980 ....................................................................... 6 Redegørelse for Historic England og English Heritage .............................................................................. 11 Begyndelsen på den engelske nationale samling ..................................................................................... 11 English -

Road Number Road Description A40 C B MONMOUTHSHIRE to 30

Road Number Road Description A40 C B MONMOUTHSHIRE TO 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY A40 START OF 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY TO END 30MPH GLANGRWYNEY A40 END OF 30 MPH GLANGRWYNEY TO LODGE ENTRANCE CWRT-Y-GOLLEN A40 LODGE ENTRANCE CWRT-Y-GOLLEN TO 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL A40 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL TO CRICKHOWELL A4077 JUNCTION A40 CRICKHOWELL A4077 JUNCTION TO END OF 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL A40 END OF 30 MPH CRICKHOWELL TO LLANFAIR U491 JUNCTION A40 LLANFAIR U491 JUNCTION TO NANTYFFIN INN A479 JUNCTION A40 NANTYFFIN INN A479 JCT TO HOEL-DRAW COTTAGE C115 JCT TO TRETOWER A40 HOEL-DRAW COTTAGE C115 JCT TOWARD TRETOWER TO C114 JCT TO TRETOWER A40 C114 JCT TO TRETOWER TO KESTREL INN U501 JCT A40 KESTREL INN U501 JCT TO TY-PWDR C112 JCT TO CWMDU A40 TY-PWDR C112 JCT TOWARD CWMDU TO LLWYFAN U500 JCT A40 LLWYFAN U500 JCT TO PANT-Y-BEILI B4560 JCT A40 PANT-Y-BEILI B4560 JCT TO START OF BWLCH 30 MPH A40 START OF BWLCH 30 MPH TO END OF 30MPH A40 FROM BWLCH BEND TO END OF 30 MPH A40 END OF 30 MPH BWLCH TO ENTRANCE TO LLANFELLTE FARM A40 LLANFELLTE FARM TO ENTRANCE TO BUCKLAND FARM A40 BUCKLAND FARM TO LLANSANTFFRAED U530 JUNCTION A40 LLANSANTFFRAED U530 JCT TO ENTRANCE TO NEWTON FARM A40 NEWTON FARM TO SCETHROG VILLAGE C106 JUNCTION A40 SCETHROG VILLAGE C106 JCT TO MILESTONE (4 MILES BRECON) A40 MILESTONE (4 MILES BRECON) TO NEAR OLD FORD INN C107 JCT A40 OLD FORD INN C107 JCT TO START OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY A40 START OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY TO CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JCT A40 CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION TO END OF DUAL CARRIAGEWAY A40 CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION TO BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT A40 BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT TO CEFN BRYNICH B4558 JUNCTION A40 BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT SECTION A40 BRYNICH ROUNABOUT TO DINAS STREAM BRIDGE A40 DINAS STREAM BRIDGE TO BRYNICH ROUNDABOUT ENTRANCE A40 OVERBRIDGE TO DINAS STREAM BRIDGE (REVERSED DIRECTION) A40 DINAS STREAM BRIDGE TO OVERBRIDGE A40 TARELL ROUNDABOUT TO BRIDLEWAY NO. -

Client Experience Guide Welcome to Our UK Facilities

Client Experience Guide Welcome to our UK facilities From our four sites in South Wales, PCI’s European operations deliver a fully integrated Molecule to Market offering for our clients. Utilising leading edge technology and unparalleled expertise, PCI addresses global drug development needs at each stage of the product life cycle, for even the most challenging applications. Hay on Wye Tredegar With extensive capability for both clinical and commercial With unparalleled capability in contained manufacture of packaging and labelling activities, the Hay-on-Wye site offers potent compounds, our Tredegar site excels as PCI’s centre clients a robust solution for primary and secondary packaging of excellence for drug manufacture. Significant investment of a variety of drug delivery forms. PCI’s expertise and in cutting edge technologies and world-class award- investments in leading packaging technologies create solutions winning facility design have enabled a truly market leading for speed-to-market and efficiency in drug supply. service for the development and manufacture of clinical and Scalable packaging technologies allow us to grow and commercial scale products. Services include formulation and evolve as project needs change through the product life analytical development, clinical trial supply, and commercial cycle, from early phase clinical development and growth into manufacturing of solid oral dose, powders, liquids and large scale clinical supply, commercial launch, and ongoing semisolids, supported by in-house packaging and labelling global supply. PCI offers bespoke packaging solutions for services and on-site laboratory services. challenging applications at its Hay facilities, including modified With over 35 years of experience in providing integrated environments for light and moisture sensitive products, drug development, PCI supports compounds from the earliest Cold Chain solutions for temperature sensitive products stages of development through to commercial launch and and biologics, specialist facilities for packaging of potent ongoing supply. -

Forthcoming MHS Events

ISSUE 35 NOVEMBER 2018 CHARITY No. 1171392 Editor: Hugh Wood, 38 Charlton Rise, Ludlow SY8 1ND; 01584 876901; [email protected] IN THIS ISSUE Forthcoming Events News Items Changes to subscription arrangements Proposed change to the constitution End of the Wigmore Church Project Wedding costumes for Roger & Joan? New Members Report MHS Visit to medieval London and the National Archives Articles Introducing the Mortimers 7 Edmund Mortimer (d.1331) and Roger Mortimer, 2nd Earl of March - Hugh Wood The Mortimers in Maelienydd: Cefnllys Castle and Abbey Cwm Hir Part of a page from the Wigmore Chronicle in Chicago The chronicle will feature in our next event on 16th February - Philip Hume in Hereford Forthcoming MHS Events Saturday 16th February 2019 - On the Record: Writing the Mortimer Family into History Medieval chronicle writing - College Hall, Hereford - see next page for details and booking Saturday 16th March 2019 - The Medieval Castle and Borough of Richards Castle AGM at 10.00; talk by Philip Hume at 11.00 - Richards Castle Village Hall -see later page for details Saturday 18th May 2019 - The Mortimers to 1330: from Wigmore to ruler of England Our Spring Conference at Leominster Priory Saturday 29th June 2019 - The Mortimer Inheritance: Key to the Yorkist Crown Joint conference with Richard III Society at Ludlow Assembly Rooms and St Laurence's Church This will be a popular event - Booking opens 1st December 2018 - see our website Wednesday 4th September 2019 - Members' Visit to Wigmore Castle and Wigmore Abbey Saturday 5th October 2019 - The Ludlow Castle Heraldic Roll: A Window into Tudor Times Saturday 30th November 2019 - Lordship and Enduring Influence: the Mortimers in Medieval Ireland Ticket Prices: members £9; non-members £13 For more information and booking click here If you are interested but don't have a computer ring Hugh on 01584 876901 News Items Membership and subscriptions - some important changes Subscription rates These have remained unchanged since the Society was formed nearly ten years ago. -

98. Clun and North West Herefordshire Hills Area Profile: Supporting Documents

National Character 98. Clun and North West Herefordshire Hills Area profile: Supporting documents www.naturalengland.org.uk 1 National Character 98. Clun and North West Herefordshire Hills Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

Hugh Wood Contact Details

NEWSLETTER 26 August 2016 Newsletter Editor: Hugh Wood Contact details: [email protected]; 01584 876901; 38 Charlton Rise, Ludlow SY8 1ND BOOK NOW - AUTUMN SYMPOSIUM IN LUDLOW - SATURDAY 1st OCTOBER - DETAILS BELOW IN THIS EDITION The Society New Members of the Society Forthcoming Events including the MHS Autumn Symposium link Recent Events and Other News link Articles Intelligence and Intrigue in the March of Wales: Maud Mortimer and the fall of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd link Isabella Mortimer: Lady of Oswestry and Clun link The Ancient Earldom of Arundel link The Ancestors of Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March link Books Fran Norton's new book - The Twisted Legacy of Maud de Braose link NEW MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY We welcome the following new members to the Society: William Barnes, Kington, Herefordshire UK Naomi Beal, Calne, Wiltshire UK And a special welcome Sara Hanna-Black, Winchester, Hampshire UK to Edward Buchan, Kington Langley, Chippenham, Wiltshire UK Charlotte Hua Stephen Chanko, Vienna, Austria from Shanghai John Cherry, Bitterley, Ludlow, Shropshire UK Lynnette Eldredge, Sequim, Washington, USA our first member from Judith Field, Potomac, Maryland USA China Charles Gunter, Little Wenlock, Shropshire UK Pauline Harrison Pogmore, Sheffield, South Yorkshire UK Christine Holmes, Barnsley, South Yorkshire UK Elizabeth Mckay, Oldham UK Jean de Rusett, Leominster, Herefordshire UK Melissa Julian-Jones, Newport, Wales UK Lynn Russell, Knowbury, Shropshire UK Paul & Stephenie Ovrom, Des Moines, Iowa, USA Gareth Wardell, Carmarthen, Wales UK Patricia Pothecary, Kingsland, Herefordshire UK Peter Whitehouse, Lingen, Herefordshire UK FORTHCOMING EVENTS Thursday 8th & Friday 9th September 2016 - An Opportunity to visit the Belltower of St James's church in Wigmore Organised by St James's, Wigmore as part of the Challenge 500 project, there will be free tours at 4pm & 5pm on both days. -

Notice of Election Powys County Council - Election of Community Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL - ELECTION OF COMMUNITY COUNCILLORS An election is to be held of Community Councillors for the whole of the County of Powys. Nomination papers must be delivered to the Returning Officer, County Hall, Llandrindod Wells, LD1 5LG on any week day after the date of this notice, but not later than 4.00pm, 4 APRIL 2017. Forms of nomination may be obtained at the address given below from the undersigned, who will, at the request of any elector for the said Electoral Division, prepare a nomination paper for signature. If the election is contested, the poll will take place on THURSDAY, 4 MAY 2017. Electors should take note that applications to vote by POST or requests to change or cancel an existing application must reach the Electoral Registration Officer at the address given below by 5.00pm on the 18 APRIL 2017. Applications to vote by PROXY must be made by 5.00pm on the 25 APRIL 2017. Applications to vote by PROXY on the grounds of physical incapacity or if your occupation, service or employment means you cannot go to a polling stations after the above deadlines must be made by 5.00 p.m. on POLLING DAY. Applications to be added to the Register of Electors in order to vote at this election must reach the Electoral Registration Officer by 13 April 2017. Applications can be made online at www.gov.uk/register-to-vote The address for obtaining and delivering nomination papers and for delivering applications for an absent vote is as follows: County Hall, Llandrindod Wells, LD1 5LG J R Patterson, Returning Officer -

The Civil War of 1459 to 1461 in the the Welsh Marches: Part 2 the Campaign and Battle of Mortimer's Cross – St Blaise's Day, 3 February 1461 by Geoffrey Hodges

The Civil War of 1459 to 1461 in the the Welsh Marches: Part 2 The Campaign and Battle of Mortimer's Cross – St Blaise's Day, 3 February 1461 by Geoffrey Hodges Recounting the bloodless battle of Ludford is relatively simple, as it is well documented. A large royal army was involved, with a fair amount of material resulting for official records and for the London chroniclers. The battle of Mortimer's Cross, however, was fought when all attention in the south-east of the kingdom was taken up by the advance of the Queen's ravaging hordes on London. The activities of Edward, Earl of March are wrapped in much obscurity; it is not at all clear what happened between the passing of the act of accord on 29 November 1460 (making the Duke of York heir to Henry VI), and the meeting between Edward and the Earl of Warwick in the Cotswolds on about 22 February 1461 -except, of course, the battle of Mortimer's Cross itself. One cannot be dogmatic about any link in this chain of events, but it is surely one of the most extraordinary stories in the annals of England and Wales, and well worth attempting to piece together. Activities of the Adversaries before the Battle What Edward's adversary, Jasper Tudor, was doing in the same period is no more certain, but it is fairly clear that, after the defeat and capture of Henry VI at Northampton on 10 July 1460, Queen Margaret fled from Coventry into Wales. Gregory says that she made first for Harlech, 'and there hens she remevyd fulle prevely unto the Lorde Jesper, Lorde and Erle of Penbroke, … ‘, who was probably at Pembroke Castle.1 Jasper seems to have grasped the strategic importance of Milford Haven as the only Welsh harbour equally accessible from France, Ireland and Scotland.2 It looks as though he and the queen (his sister-in-law and distant cousin) now planned the royalist response to the Yorkist victory; his duty would be to prepare and lead against the Yorkists in the middle Marches of Wales an expedition whose starting point would be Pembroke.