Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SDN Changes 2014

OFFICE OF FOREIGN ASSETS CONTROL CHANGES TO THE Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List SINCE JANUARY 1, 2014 This publication of Treasury's Office of Foreign AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah (a.k.a. SAHAB, Qari; IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN Assets Control ("OFAC") is designed as a a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB TUNISIA; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH; a.k.a. reference tool providing actual notice of actions by 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'AH IN TUNISIA; a.k.a. OFAC with respect to Specially Designated Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, "SUPPORTERS OF ISLAMIC LAW"), Tunisia Nationals and other entities whose property is Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) [FTO] [SDGT]. blocked, to assist the public in complying with the [SDGT]. AL-RAYA ESTABLISHMENT FOR MEDIA various sanctions programs administered by SAHAB, Qari (a.k.a. AL TOKHI, Qari Saifullah; PRODUCTION (a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIA; OFAC. The latest changes may appear here prior a.k.a. SAIFULLAH, Qari), Quetta, Pakistan; DOB a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARI'A BRIGADE; a.k.a. to their publication in the Federal Register, and it 1964; alt. DOB 1963 to 1965; POB Daraz ANSAR AL-SHARI'A IN BENGHAZI; a.k.a. is intended that users rely on changes indicated in Jaldak, Qalat District, Zabul Province, ANSAR AL-SHARIA IN LIBYA; a.k.a. ANSAR this document that post-date the most recent Afghanistan; citizen Afghanistan (individual) AL-SHARIAH; a.k.a. ANSAR AL-SHARIAH Federal Register publication with respect to a [SDGT]. -

APPLICATION of the CHARTER in UKRAINE 2Nd Monitoring Cycle A

Strasbourg, 15 January 2014 ECRML (2014) 3 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES APPLICATION OF THE CHARTER IN UKRAINE 2nd monitoring cycle A. Report of the Committee of Experts on the Charter B. Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the application of the Charter by Ukraine The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages provides for a control mechanism to evaluate how the Charter is applied in a State Party with a view to, where necessary, making recommendations for improving its language legislation, policy and practices. The central element of this procedure is the Committee of Experts, set up under Article 17 of the Charter. Its principal purpose is to report to the Committee of Ministers on its evaluation of compliance by a Party with its undertakings, to examine the real situation of regional or minority languages in the State and, where appropriate, to encourage the Party to gradually reach a higher level of commitment. To facilitate this task, the Committee of Ministers adopted, in accordance with Article 15, paragraph1, an outline for periodical reports that a Party is required to submit to the Secretary General. The report should be made public by the State. This outline requires the State to give an account of the concrete application of the Charter, the general policy for the languages protected under Part II and, in more precise terms, all measures that have been taken in application of the provisions chosen for each language protected under Part III of the Charter. The Committee of Experts’ first task is therefore to examine the information contained in the periodical report for all the relevant regional or minority languages on the territory of the State concerned. -

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

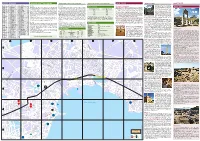

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Baltic States And

UNCLASSIFIED Asymmetric Operations Working Group Ambiguous Threats and External Influences in the Baltic States and Poland Phase 1: Understanding the Threat October 2014 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Cover image credits (clockwise): Pro-Russian Militants Seize More Public Buildings in Eastern Ukraine (Donetsk). By Voice of America website (VOA) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:VOAPro- Russian_Militants_Seize_More_Public_Buildings_in_Eastern_Ukraine.jpg. Ceremony Signing the Laws on Admitting Crimea and Sevastopol to the Russian Federation. The website of the President of the Russian Federation (www.kremlin.ru) [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ceremony_signing_ the_laws_on_admitting_Crimea_and_Sevastopol_to_the_Russian_Federation_1.jpg. Sloviansk—Self-Defense Forces Climb into Armored Personnel Carrier. By Graham William Phillips [CCBY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:BMDs_of_Sloviansk_self-defense.jpg. Dynamivska str Barricades on Fire, Euromaidan Protests. By Mstyslav Chernov (http://www.unframe.com/ mstyslav- chernov/) (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dynamivska_str_barricades_on_fire._ Euromaidan_Protests._Events_of_Jan_19,_2014-9.jpg. Antiwar Protests in Russia. By Nessa Gnatoush [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Euromaidan_Kyiv_1-12-13_by_ Gnatoush_005.jpg. Military Base at Perevalne during the 2014 Crimean Crisis. By Anton Holoborodko (http://www. ex.ua/76677715) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2014-03-09_-_Perevalne_military_base_-_0180.JPG. -

Crimea______9 3.1

CONTENTS Page Page 1. Introduction _____________________________________ 4 6. Transport complex ______________________________ 35 1.1. Brief description of the region ______________________ 4 1.2. Geographical location ____________________________ 5 7. Communications ________________________________ 38 1.3. Historical background ____________________________ 6 1.4. Natural resource potential _________________________ 7 8. Industry _______________________________________ 41 2. Strategic priorities of development __________________ 8 9. Energy sector ___________________________________ 44 3. Economic review 10. Construction sector _____________________________ 46 of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea ________________ 9 3.1. The main indicators of socio-economic development ____ 9 11. Education and science ___________________________ 48 3.2. Budget _______________________________________ 18 3.3. International cooperation _________________________ 20 12. Culture and cultural heritage protection ___________ 50 3.4. Investment activity _____________________________ 21 3.5. Monetary market _______________________________ 22 13. Public health care ______________________________ 52 3.6. Innovation development __________________________ 23 14. Regions of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea _____ 54 4. Health-resort and tourism complex_________________ 24 5. Agro-industrial complex __________________________ 29 5.1. Agriculture ____________________________________ 29 5.2. Food industry __________________________________ 31 5.3. Land resources _________________________________ -

Crimean Engineering and Pedagogical University (Simferopol)

Crimean Engineering and Pedagogical University (Simferopol) Republic Higher Educational Institution “Crimean Engineering and Pedagogical University” was created in June 1993 to meet the needs of the educational system of the Republic and the people, returned from the deportation. Nowadays it is a large regional scientific and educational complex, carrying out trainings for future specialists on educational levels "Bachelor", "Specialist" and "Master" in 24 different areas: pedagogics, economics, engineering, philology and art education. Rector of the University - Fevzi Yakubov, doctor of technical sciences, professor, Hero of Ukraine, Honored Worker of Science of Uzbekistan, Honored Worker of Education of Ukraine, winner of the National Prize T.G. Shevchenko. Responding to the general society’s requirements, since the establishment the university is focused on the three specific tasks forming its mission which he successfully resolves: • Crimean Tatars language and culture revival; • Harmonization of the integration processes in multiethnic society; • Reforms of trainings for engineering-pedagogical specialists in more liberal way. The University has about 7000 undergraduate and graduate students (approximately evenly divided into representatives of the Crimean Tatar-Turkic and Slavic cultures), employs over 400 highly qualified scientists and teachers, including more than 200 candidates and doctors of sciences, professors and associate professors. Crimean Industry and Educational system annually receives approximately 1500 graduated specialists. In the cities Kerch, Dzhankoy, Yevpatoria and Feodosia the University has opened its educational and counseling offices. The University holds highly productive scientific activity. The scientists and young specialists of the University’s departments annually publish more than 1000 scientific papers, dozens of monographs and textbooks, patents for invention; the University holds and participates in Contact: numbers of international and republican scientific conferences. -

REKABET KURULU KARARI Dosya Sayısı : 2002-4-36

Rekabet Kurumu Başkanlığından, (Danıştay Kararları Üzerine Verilen) REKABET KURULU KARARI Dosya Sayısı : 2002-4-36 (Soruşturma) Karar Sayısı : 13-29/402-179 Karar Tarihi : 21.05.2013 A. TOPLANTIYA KATILAN ÜYELER Başkan : Prof. Dr. Nurettin KALDIRIMCI Üyeler : Kenan TÜRK, Doç. Dr. Mustafa ATEŞ, İsmail Hakkı KARAKELLE, Dr. Murat ÇETİNKAYA, Reşit GÜRPINAR, Fevzi ÖZKAN B. RAPORTÖRLER: Metin HASSU, Bahar ERSOY C. BAŞVURUDA BULUNAN : - Uluslararası Nakliyeciler Derneği Nispetiye Cad. Seher Yıldızı Sk. No: 10 Etiler/İstanbul D. HAKKINDA SORUŞTURMA YAPILAN: - Karadeniz Ro-Ro İşletmesi A.Ş. Temsilcileri: Av. Dr. İ. Yılmaz ASLAN, Av. Orhan ÜNAL Gazi Umur Paşa Sok. Bimar Plaza No: 38/8 Balmumcu Beşiktaş/İstanbul (1) E. DOSYA KONUSU: 23.05.2007 tarih ve 07-42/465-177 sayılı Kurul kararının Danıştay 13. Dairesince kısmi iptali üzerine; Samsun-Novorossiysk hattında faaliyet gösteren Cenk Denizcilik Grubu ve Ulusoy Martı Ro-Ro İşletmeleri A.Ş. tarafından aynı hatta çalışan Karadeniz Ro-Ro İşletmesi A.Ş.’nin oluşturulması suretiyle 4054 sayılı Kanun'un ihlal edilip edilmediğinin tespiti. (2) F. İDDİALARIN ÖZETİ: Başvuruda, Samsun-Novorossiysk hattında çalışan Karadeniz Ro-Ro İşletmesi A.Ş. (Karadeniz Ro-Ro)’nin daha önce aynı hatta faaliyet gösteren Cenk Denizcilik Grubu (Cenk Denizcilik) ile Ulusoy Martı Ro-Ro İşletmeleri A.Ş. (Ulusoy Martı)’nin tekel yaratmak üzere birleşmesi sonucu oluştuğu ve Karadeniz Ro-Ro’nun söz konusu hatta rakiplerine nazaran aşırı fiyat uyguladığı iddia edilmektedir. (3) G. DOSYA EVRELERİ: Rekabet Kurumu kayıtlarına 18.2.2002 tarih ve 829 sayı, 24.4.2002 tarih ve 1872 sayı ile intikal eden başvurular üzerine hazırlanan 29.05.2002 tarih ve 2002-4-36/ÖA-02-OG sayılı Önaraştırma Raporu, Rekabet Kurulunun 27.6.2002 tarih ve 02-41 sayılı toplantısında görüşülmüş ve 02-41/468-196 sayı ile “… Cenk Denizcilik Ortakları ve Ulusoy Martı Ro Ro İşletmeleri A.Ş. -

1St Black Sea Conference on Ballast Water Control and Management Conference Report

1st Black Sea Conference 1st Black Sea Conference Global Ballast Water Management Programme on Ballast Water Control and Management on Ballast Water GLOBALLAST MONOGRAPH SERIES NO.3 1st Black Sea Conference on Ballast Water Control and Management Conference Report ODESSA, UKRAINE, 10-12 OCT 2001 Conference Report Roman Bashtannyy, Leonard Webster & Steve Raaymakers GLOBALLAST MONOGRAPH SERIES More Information? Programme Coordination Unit Global Ballast Water Management Programme International Maritime Organization 4 Albert Embankment London SE1 7SR United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)20 7587 3247 or 3251 Fax: +44 (0)20 7587 3261 Web: http://globallast.imo.org NO.3 A cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility, United Nations Development Programme and International Maritime Organization. Cover designed by Daniel West & Associates, London. Tel (+44) 020 7928 5888 www.dwa.uk.com (+44) 020 7928 5888 www.dwa.uk.com & Associates, London. Tel Cover designed by Daniel West GloBallast Monograph Series No. 3 1st Black Sea Conference on Ballast Water Control and Management Odessa, Ukraine 10-12 October 2001 Conference Report International Maritime Organization ISSN 1680-3078 Published in November 2002 by the Programme Coordination Unit Global Ballast Water Management Programme International Maritime Organization 4 Albert Embankment, London SE1 7SR, UK Tel +44 (0)20 7587 3251 Fax +44 (0)20 7587 3261 Email [email protected] Web http://globallast.imo.org The correct citation of this report is: Bashtannyy, R., Webster, L. & Raaymakers, S. 2002. 1st Black Sea Conference on Ballast Water Control and Management, Odessa, Ukraine, 10-12 October 2001: Conference Report. GloBallast Monograph Series No. 3. IMO London. The Global Ballast Water Management Programme (GloBallast) is a cooperative initiative of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and International Maritime Organization (IMO) to assist developing countries to reduce the transfer of harmful organisms in ships’ ballast water. -

Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security for More Information on This Publication, Visit

Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security Russia, NATO, C O R P O R A T I O N STEPHEN J. FLANAGAN, ANIKA BINNENDIJK, IRINA A. CHINDEA, KATHERINE COSTELLO, GEOFFREY KIRKWOOD, DARA MASSICOT, CLINT REACH Russia, NATO, and Black Sea Security For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA357-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0568-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Cover graphic by Dori Walker, adapted from a photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Weston Jones. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Black Sea region is a central locus of the competition between Russia and the West for the future of Europe. -

The Study of Ancient Territories Chersonesos & South Italy

The STudy of AncienT TerriTorieS Chersonesos & south Italy reporT for 2008–2011 inSTiTuTe of clASSicAl ArchAeology The univerSiTy of TexAS at Austin In Memoriam Dayton Blanchard Warren Larson Mary Link Malone Brooke Shearer Vitaly Zubar Friends and supporters Front Cover: Polynomial texture map (PTM) image of a Hellenistic or Roman banded agate intaglio signet. The PTM was created during the Reflectance Transformation Imaging workshop led by Cultural Heritage Imaging at Chersonesos in 2008. The gem, 8 mm long, bears an image of a seated, draped male figure holding a staff in one hand and perhaps sheaves of wheat in the other. Copyright © 2011 Institute of Classical Archaeology, The University of Texas at Austin www.utexas.edu/research/ica ISBN 978-0-9748334-5-3 The STudy of AncienT TerriTorieS Chersonesos & south Italy reporT for 2008–2011 inSTiTuTe of clASSicAl ArchAeology The univerSiTy of TexAS at AuSTin Copyright © 2011 Institute of Classical Archaeology The director and staff of The Institute of Classical Archaeology gratefully acknowledge the extraordinary support for operations and projects provided by The Packard Humanities Institute For additional support, special thanks to: Non-profit Organizations The Brown Foundation The James R. Dougherty, Jr. Foundation Dumbarton Oaks The Liss Foundation Cultural Heritage Imaging The Trust for Mutual Understanding Governmental Institutions Embassy of Ukraine in the United States Ministero dei Beni Culturali ed Ambientali Embassy of the United States in Ukraine Museo Archeologico Nazionale, -

COMMITTEE on the ELIMINATION of DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN (CEDAW) 62Nd Session

COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN (CEDAW) 62nd session Communication within CEDAW on violations committed by the Russian Federation on the territory of annexed Autonomous Republic of Crimea (ARC) Submitting NGOs: ‘Almenda’ Civic Education Center Center for Civil Liberties Human Rights Information Center Regional Center for Human Rights Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research (UCIPR) Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union International Charitable Organization “Roma Women Fund Chirikli” Content I. Introduction II. Violations of women’s rights committed by the Russian Federation on the territory of annexed Autonomous Republic of Crimea Discrimination of and violence against women Violations of obligations on the elimination and prevention of domestic violence Violation of the right to free choice of profession Discrimination of women in the field of employment Violations of obligations to eradicate discrimination resulting from the activities of state authorities and institutions Violations of obligations to eradicate discrimination resulting from the activities of state authorities and institutions Restriction of possibilities to own property Discrimination of Roma women Restrictions on the exercise of the right to health by women - representatives of the group of PLWA Introduction As the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (hereafter – “the Committee”) will consider the 8th periodic report of the Russian Federation on implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women at its 62nd session, the Coalition of Ukrainian NGOs submits to the Committee the statement on the violations of women’s rights committed by the Russian Federation on the territory of annexed Autonomous Republic of Crimea. -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 11, 2014 Index Hatzopoulos Marios https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 Copyright © 2014 To cite this article: Hatzopoulos, M. (2014). Index. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 11, I-XCII. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX, VOLUMES I-X Compiled by / Compilé par Marios Hatzopoulos http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX Aachen (Congress of) X/161 Académie des Inscriptions et Belles- Abadan IX/215-216 Lettres, Paris II/67, 71, 109; III/178; Abbott (family) VI/130, 132, 138-139, V/79; VI/54, 65, 71, 107; IX/174-176 141, 143, 146-147, 149 Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Abbott, Annetta VI/130, 142, 144-145, Belles-Lettres de Toulouse VI/54 147-150 Academy of France I/224; V/69, 79 Abbott, Bartolomew Edward VI/129- Acciajuoli (family) IX/29 132, 136-138, 140-157 Acciajuoli, Lapa IX/29 Abbott, Canella-Maria VI/130, 145, 147- Acciarello VII/271 150 Achaia I/266; X/306 Abbott, Caroline Sarah VI/149-150 Achilles I/64 Abbott, George Frederic (the elder) VI/130 Acropolis II/70; III/69; VIII/87 Abbott, George Frederic (the younger) Acton, John VII/110 VI/130, 136, 138-139, 141-150, 155 Adam (biblical person) IX/26 Abbott, George VI/130 Adams,