The Dialect of Grand Cayman Aarona M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amazon's Antitrust Paradox

LINA M. KHAN Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox abstract. Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a re- tailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and ex- pand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e- commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny. This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competi- tion to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the ar- chitecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive. These concerns are height- ened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have re- warded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. -

2020Annual Report

2020 Annual Report DEAR FRIENDS With the Coronavirus national emergency declaration, Northern Illinois Hospice’s priorities shifted. Leadership pivoted and narrowed its scope to worldwide pandemic infection control and keeping patients and staff safe. By April 2020, the first individual with both a terminal diagnosis and COVID-19 was admitted. Now, more than 400 days have passed and COVID-19 has become an unwanted, extended guest of the American experience. Northern Illinois Hospice continues to be diligent with its emergency management efforts. Our team has done an amazing job, demonstrating the commitment, expertise, and quality and safety practices for which we are known. Beyond COVID-19, additionally last year: • A Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) Loan was secured, which helped with payroll for several weeks during the peak of the pandemic, and Health and Human Services (HHS) stimulus funds were received to offset COVID-related expenses. • A Capital Improvement Fund was established to From left: Northern Illinois Hospice Chief Executive plan for future needs of our building. The Fund’s first Officer Lisa Novak and Board of Directors President Jon Aldrich priority was to replace the old, worn out roof. • The Board of Directors unanimously voted to expand into DeKalb County, increasing Northern Illinois Hospice’s service area from five counties to six. This mission expansion currently is underway. • Community outreach continued, and we partnered with organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association to present webinars tailored to individuals caring for seriously ill loved ones at home. We also teamed up with local nursing and assisted living facilities to offer events like Puppy Parades to bring joy to socially-isolated residents. -

Girl Names Registered in 1996

Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names # Baby Girl Names 1 Aaliyah 1 Aiesha 1 Aleeta 1 Aamino 2 Aileen 1 Aleigha 1 Aamna 1 Ailish 2 Aleksandra 1 Aanchal 1 Ailsa 3 Alena 2 Aaryn 4 Aimee 1 Alesha 1 Aashna 1Ainslay 1 Alesia 5 Abbey 1Ainsleigh 1 Alesian 1 Abbi 4Ainsley 6 Alessandra 3 Abbie 1 Airianna 1 Alessia 2 Abbigail 1Airyn 1 Aleta 19 Abby 4 Aisha 5 Alex 1 Abear 1 Aishling 25 Alexa 1 Abena 6 Aislinn 1 Alexander 1 Abigael 1 Aiyana-Marie 128 Alexandra 32 Abigail 2Aja 2 Alexandrea 5 Abigayle 1 Ajdina 29 Alexandria 2 Abir 1 Ajsha 5 Alexia 1 Abrianna 1 Akasha 49 Alexis 1 Abrinna 1Akayla 1 Alexsandra 1 Abyen 2Akaysha 1 Alexus 1 Abygail 1Akelyn 2 Ali 2 Acacia 1 Akosua 7 Alia 1 Accacca 1 Aksana 1 Aliah 1 Ada 1 Akshpreet 1 Alice 1 Adalaine 1 Alabama 38 Alicia 1 Adan 2 Alaina 1 Alicja 1 Adanna 1 Alainah 1 Alicyn 1 Adara 20 Alana 4 Alida 1 Adarah 1 Alanah 2 Aliesha 1 Addisyn 1 Alanda 1 Alifa 1 Adele 1 Alandra 2 Alina 2 Adelle 12 Alanna 1 Aline 1 Adetola 6 Alannah 1 Alinna 1 Adrey 2 Alannis 4 Alisa 1 Adria 1Alara 1 Alisan 9 Adriana 1 Alasha 1 Alisar 6 Adrianna 2 Alaura 23 Alisha 1 Adrianne 1 Alaxandria 2 Alishia 1 Adrien 1 Alayna 1 Alisia 9 Adrienne 1 Alaynna 23 Alison 1 Aerial 1 Alayssia 9 Alissa 1 Aeriel 1 Alberta 1 Alissah 1 Afrika 1 Albertina 1 Alita 4 Aganetha 1 Alea 3 Alix 4 Agatha 2 Aleah 1 Alixandra 2 Agnes 4 Aleasha 4 Aliya 1 Ahmarie 1 Aleashea 1 Aliza 1 Ahnika 7Alecia 1 Allana 2 Aidan 2 Aleena 1 Allannha 1 Aiden 1 Aleeshya 1 Alleah Baby Girl Names Registered in 1996 Page 2 of 28 January, 2006 # Baby Girl Names -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

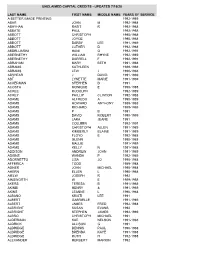

Last Name First Name Middle Name Years of Service A

UNCLAIMED CAPITAL CREDITS - UPDATED 7/16/20 LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME YEARS OF SERVICE A BETTER IMAGE PRINTING 1992-1989 ABAR JOHN M 1992-1988 ABAYHAN RASIT R 1992-1988 ABBATE PAUL 1992-1988 ABBOTT CHRISTOPH 1990-1988 ABBOTT JOYCE 1990-1988 ABBOTT DARBY LEE 1991-1989 ABBOTT LUTHER D 1992-1988 ABDELUARIM HANI O 1992-1991 ABERNETHY WILLIAM RHYNE 1992-1989 ABERNETHY DARRELL F 1992-1991 ABRAHAM MARY BETH 1991-1988 ABRAMS KATHLEEN 1989-1988 ABRAMS LEW J 1990-1988 ABSHEAR J DAVID 1991-1989 ABT LYNETTE MARIE 1991-1989 ACKERMAN STEPHEN D 1991 ACOSTA MONIQUE E 1990-1988 ACREE RUDOLPH 1992-1989 ACREY PHILLIP CLINTON 1992-1988 ADAME ALFREDO A 1990-1989 ADAMS HOWARD ANTHONY 1989-1988 ADAMS RICHARD 1989-1988 ADAMS P B 1991 ADAMS DAVID ROBERT 1990-1989 ADAMS LARA JEANE 1991 ADAMS COLLEEN 1992-1991 ADAMS CHRISTOPH ALLEN 1991-1989 ADAMS KIMBERLY ELAINE 1991-1989 ADAMS FLOYD E 1992-1988 ADAMS GLENN 1990-1988 ADAMS MALLIE 1991-1989 ADAMS KELLY N 1991-1988 ADDISON ANDREW JOHN 1991-1989 ADKINS WANDA P 1992-1989 ADORNETTO LISA JO 1990-1988 AFFERICA TODD 1989-1988 AGNER JOHN MICHAEL 1990-1988 AHERN ELLEN L 1990-1988 AIELW JOSEPH R 1992 AINSWORTH W E 1989-1988 AKERS TERESA B 1991-1988 AKINBI HENRY & 1991-1989 AKINS LEANNE L 1990-1988 ALBANO KRISTI LEE 1991 ALBERT GABRIELLE 1991-1989 ALBERT JAMES FRED 1992-1988 ALBRIGHT SUSAN EVANS 1992 ALBRIGHT STEPHEN JAMES 1992-1989 ALBRO CHRISTOPH MICHAEL 1991 ALDERMAN KAE NELSON 1991-1988 ALDRICK ALLISON G 1991 ALDRIDGE DENNIS PAUL 1990-1988 ALDRIDGE BRENDA KAYE 1991-1988 ALDRIDGE RUTH H 1992-1988 ALEXANDER HERBERT -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 a GOVERNMENT SERVICES

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2001 A GOVERNMENT SERVICES # Girl Names # Girl Names # Girl Names 1 A 1 Adelaide 4 Aisha 2 Aaisha 2 Adelle 1 Aisley 1 Aajah 1 Adelynn 1 Aislin 1 Aaliana 2 Adena 1 Aislinn 2 Aaliya 1 Adeoluwa 2 Aislyn 10 Aaliyah 1 Adia 1 Aislynn 1 Aalyah 1 Adiella 1 Aisyah 1 Aarona 5 Adina 1 Ai-Vy 1 Aaryanna 1 Adreana 1 Aiyana 1 Aashiyana 1 Adreanna 1 Aja 1 Aashna 7 Adria 1 Ajla 1 Aasiya 2 Adrian 1 Akanksha 1 Abaigeal 7 Adriana 1 Akasha 1 Abang 11 Adrianna 1 Akashroop 1 Abbegael 1 Adrianne 1 Akayla 1 Abbegayle 1 Adrien 1 Akaysia 15 Abbey 1 Adriene 1 Akeera 2 Abbi 3 Adrienne 1 Akeima 3 Abbie 1 Adyan 1 Akira 8 Abbigail 1 Aedan 1 Akoul 1 Abbi-Gail 1 Aeryn 1 Akrity 47 Abby 1 Aeshah 2 Alaa 3 Abbygail 1 Afra 1 Ala'a 2 Abbygale 1 Afroz 1 Alabama 1 Abbygayle 1 Afsaneh 1 Alabed 1 Abby-Jean 1 Aganetha 5 Alaina 1 Abella 1 Agar 1 Alaine 1 Abha 6 Agatha 1 Alaiya 1 Abigael 1 Agel 11 Alana 83 Abigail 2 Agnes 1 Alanah 1 Abigale 1 Aheen 4 Alanna 1 Abigayil 1 Ahein 2 Alannah 4 Abigayle 1 Ahlam 1 Alanta 1 Abir 2 Ahna 1 Alasia 1 Abrial 1 Ahtum 1 Alaura 1 Abrianna 1 Aida 1 Alaya 3 Abrielle 4 Aidan 1 Alayja 1 Abuk 2 Aideen 5 Alayna 1 Abygale 6 Aiden 1 Alaysia 3 Acacia 1 Aija 1 Alberta 1 Acadiana 1 Aika 1 Aldricia 1 Acelyn 1 Aiko 2 Alea 1 Achwiel 1 Aileen 7 Aleah 1 Adalien 1 Aiman 1 Aleasheanne 1 Adana 7 Aimee 1 Aleea 2 Adanna 2 Aimée 1 Aleesha 2 Adara 1 Aimie 2 Aleeza 1 Adawn-Rae 1 Áine 1 Aleighna 1 Addesyn 1 Ainsleigh 1 Aleighsha 1 Addisan 12 Ainsley 1 Aleika 10 Addison 1 Aira 1 Alejandra 1 Addison-Grace 1 Airianna 1 Alekxandra 1 Addyson 1 Aisa -

AAMA) List Updated 9/17/2020

Connecticut residents that are CMAs (AAMA) List Updated 9/17/2020 First Name Last Name Credential Karin Abalan CMA (AAMA) Emma Abruzzo CMA (AAMA) Camice Acevedo CMA (AAMA) Nathalie Acevedo-Muniz CMA (AAMA) Margarita Acosta CMA (AAMA) Vickie Adams CMA (AAMA) Jamil Ahmed CMA (AAMA) Jennifer Aiken CMA (AAMA) Sahbaa Al Bayati CMA (AAMA) Alyssa Alarcon CMA (AAMA) Betsy Aldridge CMA (AAMA) Brittani Algarin CMA (AAMA) Zenaida Alicea CMA (AAMA) Scarlett Alquijay CMA (AAMA) Ana Alvarez CMA (AAMA) Brianda Alvarez CMA (AAMA) Jennifer Amaral CMA (AAMA) Charlene Ames CMA (AAMA) Elisa Kelly Amill CMA (AAMA) Tina Ammerman CMA (AAMA) Holly Anderson CMA (AAMA) Ryan Anderson CMA (AAMA) Frances Andino CMA (AAMA) Brandi Andres CMA (AAMA) Theresa Andrews CMA (AAMA) Sandra Angel CMA (AAMA) Lorie Annatone CMA (AAMA) Kayla Anseeuw CMA (AAMA) Michelle Antonini CMA (AAMA) Bonnie Appleton CMA (AAMA) Parthena Athanasiades CMA (AAMA) Monica Auclair CMA (AAMA) Deirdre Austin CMA (AAMA) Raegan Avallone CMA (AAMA) Stephanie Avila CMA (AAMA) Rosalyn Aybar CMA (AAMA) Magali Ayres CMA (AAMA) Jessica Backer CMA (AAMA) Kristin Bacon CMA (AAMA) Jonathan Baez CMA (AAMA) Florina Balavender CMA (AAMA) Lyndsay Baldwin CMA (AAMA) Sally Ballantoni CMA (AAMA) Mickell Balonze CMA (AAMA) Connecticut residents that are CMAs (AAMA) List Updated 9/17/2020 Niloufer Banaji CMA (AAMA) Kimberly Bankowski CMA (AAMA) Amber Barber CMA (AAMA) Laura Barbero CMA (AAMA) Michael Barbieri-May CMA (AAMA) Kimberly Barbour CMA (AAMA) Rebecca Barnes CMA (AAMA) Crystal Barnes CMA (AAMA) Naomi Barone CMA -

Little Cayman Brochure

Final-CI-LC-NatureBrochure-2016 ART-US REV_LC-NatureBrochure-8 2/24/17 4:05 PM Page 1 Red-footed booby Little Cayman’s natural beauty Welcome CAYMAN ISLANDS Heritage Sites & Trails BOOBY POND is a designated to Little Cayman— wetland of international Little Cayman importance, a RAMSAR site, Heritage Sites and Trails the tiny pristine that protects the largest island that is our home. colony of red-footed booby Here natural beauty – in the Caribbean, a and cultural history Little Cayman is the smallest and most tranquil magnificent frigatebird remain closely colony and a large heronry. of the Caribbean’s three sparkling jewels known interwoven and our concessions to civilisation are few. The reserve is also a winter as the Cayman Islands. EXPLORE a nature lover’s paradise where the sound of the outdoors haven for large numbers of Its ten square miles of unspoiled habitat and surrounds you on a hike along the Salt Rock Nature Trail. migrant land-birds and protected heritage offer the ultimate escape. LITTLE CAYMAN Discover orchids, butterflies and birds in the forest; and a pirates herons, waders, shorebirds Explore, relax and bask in perfect natural beauty. well and the remnants of phosphate mines from the 1800s. and terns. A Nature Lover’s THE CALL OF THE SEA is irresistible A BIRD WATCHER’S DREAM. USA MIAMI Paradise here. You can snorkel in the The island is home to up to 200 species shallow reef-protected including 20,000 red- CAYMAN sounds or dive the famous footed boobies and an ISLANDS Bloody Bay Wall. -

Open Amber Lambert Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Education WOMEN IN ENGINEERING: THE GENDERED EFFECTS OF PROGRAM CHANGES, FACULTY ACTIVITIES, AND STUDENT EXPERIENCES ON LEARNING A Dissertation in Higher Education Administration by Amber D. Lambert © 2008 Amber D. Lambert Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2008 ii The thesis of Amber D. Lambert was reviewed and approved* by the following: Patrick T. Terenzini Distinguished Professor of Higher Education Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Lisa R. Lattuca Associate Professor of Higher Education Duane F. Alwin McCourtney Professor of Sociology Gül Kremer Affiliate Faculty of Industrial Engineering Assistant Professor of Engineering Design Dorothy Evensen Professor of Education In Charge of the Graduate Program in Higher Education *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii Abstract Creating gender equity in engineering education is important for more reasons than simply being a matter of social justice or diversifying the engineering field. It is also a significant educational and public policy issue that will affect the future economic competitiveness of the United States in the global marketplace. Engineering is arguably the leading national example of a profession in which women are under-represented. Undergraduate engineering programs not only need to attract and retain female students, but they must also provide full access to the educational experiences women must have to develop the engineering skills to succeed in the engineering profession. This study explored whether the shift to the “soft” or less technical skills in engineering encouraged by new accreditation standards could potentially have had differential effects for women in engineering from their male counterparts. -

Cayman International School New Faculty & Staff 2018-19

Cayman International School New Faculty & Staff 2018-19 Melody Meade (Early Childhood Principal) Melody Meade joins CIS in the newly created position of Early Childhood Principal. Melody has worked as a teacher and in school administration in middle school, elementary school and Early Childhood divisions. She is thrilled to devote her energies and focus to the school experience of our youngest learners. Melody earned her Masters Degree in Education Administration from Columbia University: Teachers College, graduating from the Klingenstein Center for Private School Leadership. Her BA degree is in Elementary Education and History, from the University of Rhode Island. Originally from Storrs Ct. Melody has devoted her career to international education. She has worked in NYC, San Francisco, Brazil, France, and Belgium. She joins us from Washington DC, where she was the Primary School Principal at Washington International School, where her two children graduated earning bilingual IB Diplomas. Mike Neeland (MS Science) and Carol Neeland (ES Technology Integration) Mike Neeland grew up in Kansas and taught in Topeka before moving to Barcelona to teach MS and HS science at Benjamin Franklin International School. Carol grew up in California and taught in San Clemente for seven years before accepting a position as the K – 12 Computer Teacher at Ben Franklin IS. They met and married in Spain. They moved to Taiwan where Carol worked as an ES computer teacher and Mike was Assistant Aquatics Director and MS science teacher at Taipei American School. Their daughter, Kelsey, was born in Taipei. Next stop, the Dominican Republic to work at Carol Morgan School. -

Federal Register/Vol. 77, No. 22/Thursday, February 2, 2012

5308 Federal Register / Vol. 77, No. 22 / Thursday, February 2, 2012 / Notices opportunity to comment on proposed Current Actions: There is no change to information; (c) ways to enhance the and/or continuing information this existing regulation. quality, utility, and clarity of the collections, as required by the Type of Review: Extension of a information to be collected; (d) ways to Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995, currently approved collection. minimize the burden of the collection of Public Law 104–13 (44 U.S.C. Affected Public: Individuals and information on respondents, including 3506(c)(2)(A)). business or other for-profit through the use of automated collection DATES: Written comments should be organizations. techniques or other forms of information received on or before April 2, 2012 to Estimated Number of Respondents: 4. technology; and (e) estimates of capital be assured of consideration. Estimated Time per Respondent: 30 or start-up costs and costs of operation, minutes. maintenance, and purchase of services ADDRESSES: Direct all written comments Estimated Total Annual Burden to provide information. to Yvette Lawrence, Internal Revenue Hours: 2. Service, room 6129, 1111 Constitution Approved: January 24, 2012. The following paragraph applies to all Yvette Lawrence, Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20224. of the collections of information covered IRS Reports Clearance Officer. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: by this notice: Requests for additional information or An agency may not conduct or [FR Doc. 2012–2265 Filed 2–1–12; 8:45 am] copies of the regulations should be sponsor, and a person is not required to BILLING CODE 4830–01–P directed to R. -

H Peschianna

H □ PESCHIANNA Foreword Once again as the door closes on another school year at Hopedale High, we look bock to a year full of both sod and happy memories. For the Freshmen it opened the door to a bright new world. For the Sophomores and Juniors the year was full of work and gay times. For the Seniors it is the final "good bye". But for all it is the end of another year. So these memories will not be lost or forgotten, the Hopeschianno has attempted to capture and record these memories. It can serve as the key in later years as we look through it, to open the door of our memories of that delightful year at Hopedale High in 1958-59. HOPEDALE HIGH SCHOOL Hopedale, Ohio HOPESCHIANNA Hopeschianna Pub Iished By SEN IOR CLASS HOPEDALE HIGH SCHOOL FACULTY ADVISOR: Lester A. Hickman Staff EDITOR: .•..••..••..••.••. Kay Stringer PHOTOGRAPHERS ••. .Chuck Marinacci Assistant Editor • • •. • ••••. Shirley Carman . .•• •• Bernard Kuryn SECRET ARY •. ....••.•• Joanne Murdock TYPISTS .•• . .•••••••••• Carol Pizzino PR OP HETS .• . •.•...•• . .•••Peggy Kenton ••.•.• •••• •. Joyce Davenport ••.••.••• •••. Jeannie Penoyer •• . •. ••.••. • ••.•• ••• Lois Ash SALES MANAGERS ..••••••• Gary Voich ROOM ED ITOR .••• • .•••• David Cox .••..• Ronnie Carlon SPORTS EDITOR ..••.•••• . • Rich Rensi ADVERTIZING: •.•..••.•• Larry Wohnhas ACTIV ITI ES ED ITOR •••• Eddie Pizzino MANAGERS •••• • •••• Gordon Ligget HISTORIAN .•••.••••• .•• Robert Black 4 this annual, . We, the da" af 1959o~ ieldedicate Ca,de,, _who h""as soaf pat1enth;gh - Hopesch,anna, h our junior an ly gu1'ded . us througto M r • . d senior ye school . 6 Hopedale Local School District LESTER A . HICKMAN, Superintendent Hopedale, Ohio Board of Education To the Members of the Graduating C lass of 1959: Th is letter comes to you with my warmest congratulations for a job we 11 done.