Evgeny Vasiukov Chess Champion of Moscow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Modernized Grünfeld Defense

The Modernized Grünfeld Defense First edition 2020 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2020 Yaroslav Zherebukh All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. All sales or enquiries should be directed to Thinkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Website: www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor: Romain Edouard Assistant Editor: Daniël Vanheirzeele Typesetting: Mark Haast Proofreading: Bob Bolliman Software: Hub van de Laar Cover Design: Iwan Kerkhof Graphic Artist: Philippe Tonnard Production: BESTinGraphics ISBN: 9789492510792 D/2020/13730/7 The Modernized Grünfeld Defense Yaroslav Zherebukh Thinkers Publishing 2020 Key to Symbols ! a good move ⩲ White stands slightly better ? a weak move ⩱ Black stands slightly better !! an excellent move ± White has a serious advantage ?? a blunder ∓ Black has a serious advantage !? an interesting move +- White has a decisive advantage ?! a dubious move -+ Black has a decisive advantage □ only move → with an attack N novelty ↑ with initiative ⟳ lead in development ⇆ with counterplay ⨀ zugzwang ∆ with the idea of = equality ⌓ better is ∞ unclear position ≤ worse is © with compensation for the + check sacrificed material # mate Table of Contents Key to Symbols ......................................................................................................... -

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev by Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All Rights Reserved

Correspondence Chess News Issue 31 - 14 January 2001 An Interview with FIDE GM Mikhail Golubev By Santhosh Matthew Paul Copyright 2001 by Santhosh Matthew Paul, All rights reserved. How did you first get attracted to chess? Please also say something about your early chess development in Ukraine. I started to play in 1976 (at the age of six) and from 1977 onwards, I started to learn chess in the chess club (by the way, many players the world over think that chess was an obligatory discipline in the regular Soviet Schools – that’s not correct). Sometimes, I think that I started to look at chess seriously after my parents got divorced, but I’m not sure if it was the real impetus. In any case, I was quite able to play chess. It is easy to say as I scored many good results, especially at the age of 12-14 years. For instance, in the 1984 (at age 14), I shared second place (with the better tiebreak) with Ivanchuk (he was one year older) in the Ukrainian Junior Ch U- 17. Still, I’m not sure if I’m a born chess player. I remember, in 1984 I played in a junior tournament in Baku, and shared the first place there with Vladimir Akopian. Volodya is one year younger than me, and he was very small in 1984 J . We played an extremely complicated game, and I accepted his draw offer when my position was already better. I was quite afraid for him, as for the first time I saw a clearly more talented player than me. -

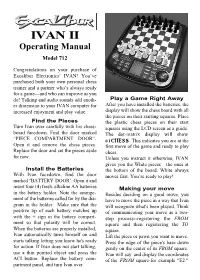

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712

IVAN II Operating Manual Model 712 Congratulations on your purchase of Excalibur Electronics’ IVAN! You’ve purchased both your own personal chess trainer and a partner who’s always ready for a game—and who can improve as you do! Talking and audio sounds add anoth- Play a Game Right Away er dimension to your IVAN computer for After you have installed the batteries, the increased enjoyment and play value. display will show the chess board with all the pieces on their starting squares. Place Find the Pieces the plastic chess pieces on their start Turn Ivan over carefully with his chess- squares using the LCD screen as a guide. board facedown. Find the door marked The dot-matrix display will show “PIECE COMPARTMENT DOOR”. 01CHESS. This indicates you are at the Open it and remove the chess pieces. first move of the game and ready to play Replace the door and set the pieces aside chess. for now. Unless you instruct it otherwise, IVAN gives you the White pieces—the ones at Install the Batteries the bottom of the board. White always With Ivan facedown, find the door moves first. You’re ready to play! marked “BATTERY DOOR’. Open it and insert four (4) fresh, alkaline AA batteries Making your move in the battery holder. Note the arrange- Besides deciding on a good move, you ment of the batteries called for by the dia- have to move the piece in a way that Ivan gram in the holder. Make sure that the will recognize what's been played. Think positive tip of each battery matches up of communicating your move as a two- with the + sign in the battery compart- step process--registering the FROM ment so that polarity will be correct. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

The Modernized Grünfeld Defense

The Modernized Grünfeld Defense First edition 2020 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2020 Yaroslav Zherebukh All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. All sales or enquiries should be directed to Thinkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Website: www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor: Romain Edouard Assistant Editor: Daniël Vanheirzeele Typesetting: Mark Haast Proofreading: Bob Bolliman Software: Hub van de Laar Cover Design: Iwan Kerkhof Graphic Artist: Philippe Tonnard Production: BESTinGraphics ISBN: 9789492510792 D/2020/13730/7 The Modernized Grünfeld Defense Yaroslav Zherebukh Thinkers Publishing 2020 Key to Symbols ! a good move ⩲ White stands slightly better ? a weak move ⩱ Black stands slightly better !! an excellent move ± White has a serious advantage ?? a blunder ∓ Black has a serious advantage !? an interesting move +- White has a decisive advantage ?! a dubious move -+ Black has a decisive advantage □ only move → with an attack N novelty ↑ with initiative ⟳ lead in development ⇆ with counterplay ⨀ zugzwang ∆ with the idea of = equality ⌓ better is ∞ unclear position ≤ worse is © with compensation for the + check sacrificed material # mate Table of Contents Key to Symbols ......................................................................................................... -

Solingen (Unregular)

Solingen (unregular) International tournaments 1968 (100th anniversary tournament of the Solingen Chess Club) Lengyel clear first, ahead of 2. Parma, 3.-7. Pachman, Szabo, Damjanovic, Janosevic (16 players, including O’Kelly, Donner, Medina, Tatai, Lehmann, and Wade who wrote a tournament book; IM Gerusel shared 8th place). This was maybe Levente Lengyel’s (GM in 1964) finest tournament win, he also won at Rome 1964 (joint with Lehmann), Bari 1972 outright, and Reggio Emilia 1972/73 (joint with Popov and Torre). MATHIAS GERUSEL (born Feb-05-1938) Germany Mathias Gerusel is a (West) German IM who finished second to William James Lombardy at the World Junior Championship (1967). He went on to study mathematics. His best tournament results have been 3rd at Büsum 1969 after Bent Larsen and Lev Polugaevsky, and 5th= at Solingen 1974. 1974 Polugaevsky, Kavalek, ahead of 3.-4. Spassky, Kurajica, (15 players, Pachman boycotted), IM Gerusel shared 5th place together with Szabo, Liberzon, and Westerinen, above 9. Uhlmann; including also Heinz Lehmann, and Hajo Hecht) ttp://www.teleschach.de/historie/solingen1974.htm (Standings) http://www.zeit.de/1974/30/der-ausdruck-des-bedauerns (Boycott of Pachman) 1986 (international club championship) Hübner clear first, ahead of 2./3. IM Ralf Lau, Short (Lau beat Short in their direct game) 4. Kavalek, 5.-6 Spassky, IM Lucas Brunner, 7.-8. Sunye-Neto, Westerinen (12 players, among them German IM Capelan who played already in 1968 and in 1974). Note: Brunner vs. Schneider (https://www.365chess.com/game.php?gid=2169447) has a wrong score, Brunner won Ralf Lau achieved his third an final GM norm to become a grandmaster. -

CHESS INFORMANT Contain

Drawing by Bob Brandreth , The , E"..-y ail: mono. the Yuqoalav ChI .. Federation brings out a Dew book of the tin.. 1 gom.. plared dwinq the preceding baH y.ar. A unique. Dewly-deviled aystem of annotating gwu_ by coded ligna moida all languuge obetcd... 1'Ju. malt. possible a univeraally usable and yet V'Osonably-priced book which brings the neweat ideaa in the opening,; and throughout the game to every ch.. enthusiast more quickly U"m ever before. Book 6 confaina 821 gam.. played between July 1 and D.cember 31, 1968. A qreat aelectiOD of theoretically important gam_ from 28 toumcnrumta and match.. , inc1uding the Lugano Olympiad. World Student Team Cbmnpionsbip (Ybb.), Mar del Plata. Netanya, Amaterdam. Skopje, Debrecen, Sombot. Havana. Vinkovci, Belgrade, Palma d. Majorca, and Athens, S.pacial New Featurel Beginning with Book 6. each CHESS INFORMANT contain. a aection for FIDE communicati0D8, re placing the former official publication FIDE REVIEW. The FIDE section in this iau. contains comple'e Regu1ationa for the Toumamenta and Match BII for the Men'. and l.cdl·,' World CbampiC'Dlhipa. Pr.. crih n the entire competition .,atem from Zonal cmd Interzonal Toummnenta throuqb the Ccmdidatea Matches to the World Championship Match. Book 6 has aections leaturing 51 brilliant Combinations and 45 Endings from actual play during the preceding six months. Another interesting feature ia a table listing in Older the Ten Beat Gam,ea from Book 5 and showing how each of the eight Grandmastem on the jury voted. Contains an Engliah·lanquage introduction. esplanation of the annotation cod•• indez of play em and comm._tcrton. -

October 2020 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 47, Number 4 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION October 2020 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT My Love Affair With the Royal Game Volume 47, Number 4 Colorado Chess Informant October 2020 From the Editor We are still in the thick of it. Online chess only since this mess broke out. It is tough but we are getting through it. I hope all is well and that you are healthy and reasonably happy. There is some hope of chess life going on around the world with a few, and I mean very few, over-the-board tournaments being The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a played. So far I have not heard of any covid-19 outbreaks at Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- these tournaments. Hopefully it stays that way. tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are Now with online play there has now been a Grandmaster caught tax deductible. cheating while playing on Pro Chess League resulting in being Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) banned for life from Chess.com. You can read about it here: memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to https://en.chessbase.com/post/cheating-controversy-at- additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- prochessleague. Such a shame and so unnecessary. tic tournament membership is available for $3. Fortunately no such incident in Colorado. I again want to hand ● Send address changes to Ann Davies. out Honorable Mentions to those Directors and Organizers run- ● Send pay renewals & memberships to Dean Brown. -

FIDE Trainers Committee V22.1.2005

FIDE Training! Don’t miss the action! by International Master Jovan Petronic Chairman, FIDE Computer & Internet Chess Committee In 1998 FIDE formed a powerful Committee comprising of leading chess trainers around the chess globe. Accordingly, it was named the FIDE Trainers Committee, and below, I will try to summarize the immense useful information for the readers, current major chess training activities and appeals of the Committee, etc. Among their main tasks in the period 1998-2002 were FIDE licensing of chess trainers and the recognition of these by the International Olympic Committee, benefiting in the long run, to all chess federations, trainers and their students. The proven benefits of playing and studying chess have led to countries, such as Slovenia, introducing chess into their compulsory school curiccullum! The ASEAN Chess Academy, headed by FIDE Vice President, FM, IA & IO - Ignatius Leong, has organized from November 7th to 14th 2003 - a Training Course under the auspices of FIDE and the International Olympic Committee! IM Nikola Karaklajic from Serbia & Montenegro provided the training. The syllabus was targeted for middle and lower levels. At the time, the ASEAN Chess Academy had a syllabus for 200 lessons of 90 minutes each! I am personally proud of having completed such a Course in Singapore. You may view the official Certificate I received here. Another Trainers’ Course was conducted by FIDE and the Asean Chess Academy from 12th to 17th December 2004! Extensive testing was done, here is the list of the candidates who had passed the FIDE Trainer high criteria! The main lecturer was FIDE Senior Trainer Israel Gelfer. -

Nuestro Círculo

Nuestro Círculo Año 10 Nº 451 Semanario de Ajedrez 26 de marzo de 2011 RATMIR D. KHOLMOV 1.e4 e5 2.Cf3 Cc6 3.Ab5 Cd4 4.Cxd4 exd4 39.Td2 Tb5+ 40.Txb5 axb5 41.Ta2 Rc6 5.0-0 c6 6.Ac4 Cf6 7.De2 d6 8.e5 dxe5 42.Ta7 0-1 1925 - 2006 9.Dxe5+ Ae7 10.Te1 b5 11.Ab3 a5 12.a4 Fischer,R - Kholmov,R [C98] Ta7 13.axb5 0-0 14.b6 Dxb6 15.d3 Ab4 Capablanca mem Habana, 1965 16.Tf1 Dd8 17.Ag5 Te8 18.Dg3 Ae6 19.Axe6 Txe6 20.Cd2 h6 21.Axf6 Txf6 22.Ce4 Te6 1.e4 e5 2.Cf3 Cc6 3.Ab5 a6 4.Aa4 Cf6 5.0-0 23.Dh3 Dd5 24.c3 dxc3 25.bxc3 Ae7 26.f4 f5 Ae7 6.Te1 b5 7.Ab3 0-0 8.c3 d6 9.h3 Ca5 27.c4 Dd4+ 28.Rh1 g6 29.Tab1 h5 30.Tb8+ 10.Ac2 c5 11.d4 Dc7 12.Cbd2 Cc6 13.dxc5 Rf7 31.Dg3 fxe4 32.f5 Tf6 33.Th8 Dxd3 dxc5 14.Cf1 Ae6 15.Ce3 Tad8 16.De2 c4 34.fxg6+ Rg7 35.Th7+ Rg8 36.Dxd3 exd3 17.Cg5 h6 18.Cxe6 fxe6 19.b4 Cd4! 20.cxd4 37.Txf6 Axf6 38.Txa7 Ad4 39.Tf7 d2 40.Tf1 [20.Df1 Cxc2 21.Cxc2 Td3!µ] 20...exd4 Ab2 41.Rg1 a4 42.Rf2 a3 43.Re2 a2 0-1 21.a3 d3 22.Axd3 Txd3 23.Cg4 Rh7 24.e5 Cxg4 25.De4+ g6 26.Dxg4 Tf5 27.De4 Dd7 Petrosian,T - Kholmov,R [D19] 28.Ae3 Dd5 29.Dxd5 Txd5 30.f4 g5 31.g3 Vilnius, 1951 gxf4 32.gxf4 Tf8 33.Rg2 Rg6 34.Tg1 Td3 35.Rf3+ Rf5 36.Tg7 Ad8 37.Tb7 Tg8 38.Tb8 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Cc3 Cf6 4.Cf3 dxc4 5.a4 Tg7 39.a4 h5 40.axb5 axb5 41.Txb5 Ah4 Af5 6.e3 e6 7.Axc4 Ab4 8.0-0 0-0 9.De2 Ag4 42.Re2 Tg2+ 43.Rf1 Th2 44.Rg1 Te2 45.Ab6 10.h3 Axf3 11.Dxf3 Cbd7 12.Td1 a5 13.e4 e5 c3 46.Rf1 Th2 0-1 14.Ag5 exd4 15.Txd4 Ce5 16.Dd1 De7 17.Ae2 h6 18.Ah4 Cg6 19.Axf6 Dxf6 20.Ag4 Kholmov,R - Bronstein,D [B99] Ce5 21.Tc1 Ac5 22.Td2 Tad8 23.Cd5 cxd5 Kiev, 1964 24.Txc5 dxe4 25.De2 Cd3 26.Tb5 Dd4 27.De3 Dxa4 28.Txb7 Dc6 29.Db6 Dc1+ Esta partida recibió el premio de belleza del 30.Td1 Dg5 31.Ta7 Td5 32.De3 De5 33.Ae2 Campeonato de la URSS 1964/1965 1.e4 c5 Ratmir Dmitrievich Kholmov nació el 13 de Dxb2 34.Dxe4 Cxf2 35.Tb7 Txd1+ 36.Axd1 2.Cf3 Cf6 3.Cc3 d6 4.d4 cxd4 5.Cxd4 a6 mayo de 1925 en Shenkursk, Rusia.