Classrooms As the Construction Site for Literacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

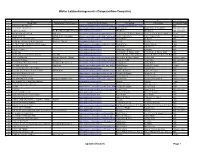

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

Billboard 1974-08-24

NEWSPAPER Bill The International Music -Record -Tape Newsweekly August 24, 1974 $1.25 A Billboard Publication Nixon Furore Slows Davis Calls Texaco Sued In Copyright Movement Promo Slot Tape Piracy Test By MILDRED HALL A Hot Seat By STEPHEN Panasonic Sets By IS HOROWITZ TRAIMAN WASHINGTON -The aftermath NEW YORK -In what may develop as a precedent- setting piracy test case, NEW YORK -Promotion is of the Nixon resignation has set in now Custom Publishing Co. and Camad Music Co. have filed suit against Texaco, Expansion Move second only to aecr as the "hot seal" motion a new series of delays in alleging copyright infringement on songs appearing on tapes alleged to be of the rc nrd industry. Clive Davis Congress for all pending copyright Hy RADCLIFFE JOE bootleg reproductions and sold at an Illinois Texaco station. The oil firm has told an audience of mire than at bills -including the general revision NEW YORK -Panasonic Au- 600 denied the allegations. the opening session of Billboard's bill 5.1361, the House antipiracy bill tomotive Products Dept. will utilize A ruling for the plaintiffs could seventh Annual International Radio H.R. 13364. and the hoped -for ex- network television, as well as trade UA Restructures establish the important precedent in Programming Forum here Wednes- tension legislation to save expiring and consumer print media- in a mas- piracy litigation of a parent com- copyrights. sive promotion campaign that Cal day (14). Into 5 Divisions pany being held liable for actions of Released from the harrowing job Shore, vice president and general The acting Bell Records chief, in By NAT ERI'EDI.AND its agents -in this' case, an ail com- of impeaching a president, both manager of Panasonic's special his first major address to an industry LOS ANGELES- United Artists pany held accountable for activities a the Senate and House began lengthy products division, tails a major in- audience since leaving presi- bas reorganized its non -film oper- of its franchised stations. -

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List ID# Song Title Arranger I03803 'TIL I HEAR YOU SING (From LOVE NEVER DIES) June Berg I04656 (YOUR LOVE HAS LIFTED ME) HIGHER AND HIGHER Becky Wilkins and Suzanne Wittebort I00008 004 MEDLEY - HOW COULD YOU BELIEVE ME Sylvia Alsbury I00011 005 MEDLEY - LOOK FOR THE SILVER LINING Mary Ann Wydra I00020 011 MEDLEY - SISTERS Dede Nibler I00024 013 MEDLEY - BABY WON'T YOU PLEASE COME HOME* Charlotte Pernert I00027 014 MEDLEY - CANADIAN MEDLEY/CANADA, MY HOME* Joey Minshall I00038 017 MEDLEY - BABY FACE Barbara Bianchi I00045 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - CONTEST VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I00046 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - SHOW VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I02517 028 MEDLEY - I WANT A GIRL Barbara Bianchi I02521 031 MEDLEY - LOW DOWN RYTHYM Barbara NcNeill I00079 037 MEDLEY - PIGALLE Carolyn Schmidt I00083 038 MEDLEY - GOD BLESS THE U.S.A. Mary K. Coffman I00139 064 CHANGES MEDLEY - AFTER YOU'VE GONE* Bev Sellers I00149 068 BABY MEDLEY - BYE BYE BABY Carolyn Schmidt I00151 070 DR. JAZZ/JAZZ HOLIDAY MEDLEY - JAZZ HOLIDAY, Bev Sellers I00156 072 GOODBYE MEDLEY - LIES Jean Shook I00161 074 MEDLEY - MY BOYFRIEND'S BACK/MY GUY Becky Wilkins I00198 086 MEDLEY - BABY LOVE David Wright I00205 089 MEDLEY - LET YOURSELF GO David Briner I00213 098 MEDLEY - YES SIR, THAT'S MY BABY Bev Sellers I00219 101 MEDLEY - SOMEBODY ELSE IS TAKING MY PLACE Dave Briner I00220 102 MEDLEY - TAKE ANOTHER GUESS David Briner I02526 107 MEDLEY - I LOVE A PIANO* Marge Bailey I00228 108 MEDLEY - ANGRY Marge Bailey I00244 112 MEDLEY - IT MIGHT -

The Prairie Wind Fall, 2007 Fall’S Bountiful Harvest 18 Table of Contents Revise Yourself 19 Greeting 2 to Be Or Not to Be

Season's Crop 18 The Prairie Wind Fall, 2007 Fall’s Bountiful Harvest 18 Table of contents Revise Yourself 19 Greeting 2 To Be or Not to Be . Whoever I Am (That is the Autumnatically Yours 2 Answer) 19 from the editor 2 Promote That Book! 21 Falling Into Place 2 Simple, Inexpensive Ways to Promote Your Book Illustrator in the Spotlight 3 Everyday 21 SCBWI-Illinois’ Artists Put on a Show 3 Opportunities 21 Tales from the Front 4 IWPA’s Call For Authors 21 The Girl from W.R.I.T.E.R. 4 Kidslitosphere 22 Someone You Should Know 6 Why Do Bloggers Blog? 22 Illinois Reading Council’s Roxanne Owens 6 Booksellers' Perspective 25 Writing Tips 8 Let’s Have a Party: An Introduction to a Study on Parental Revelry 25 To Outline or Not To Outline? That is the Question 8 Fitness + Writing 26 Critique Group Tips 9 Writing! It’s Just like Exercise 26 Five Elements That Make a Solid Group 9 op/ed 27 Illustrator Tips 10 Publishing the Digital Way 27 From Cornfields to Cyberspace 10 Horoscopes 32 Writer's Bookshelf 13 Nuggets from Nunki: Horoscopes for Children’s Recommended Reads to Hone Your Craft 13 Book Writers and Illustrators 32 News Roundup 14 October Is National Book Month! 14 Food for Thought 15 Sept. 15th Eat and Greet for Published SCBWI Members With Trade Books 15 A Fly on the Wall 16 Carolyn Yoder Workshop June 23-24 16 Don't Miss 16 Prairie Writer’s Day Is Coming 16 The Prairie Wind, Fall 2007 Copyright SCBWI-Illinois p. -

Menus for State Dinners During the Carter Administration

Menus for State Dinners during the Carter Administration President Jose Lopez Portillio of Mexico February 14, 1977 Dinner: Shrimp Gumbo Soup Corn Sticks Paul Mason Rare Sherry Supreme of Capon in White Grape Sauce Saffron Rice Asparagus Tips in Butter Charles Krug Gamay Beaujolais Hearts of Lettuce Salad Trappist Cheese Schramsberg Blanc de Blanc Burnt Almond Ice Cream Ring Butterscotch Sauce Cookies Demitasse Entertainment: Rudolf Serkin Program Prelude and Fugue in E minor, Felix Mendelssohn Sonata in F minor, Op. 57, Ludwig van Beethoven (“Appassionata”) Allegro assai Andante con moto (variazioni); Allegro ma non troppo-Presto Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau of Canada February 21, 1977 Dinner: Alaskan King Crab in Herb Sauce Saint Michelle Chenin Blanc Roast Stuffed Saddle of Lamb Timbale of Spinach Glazed Carrots Louis Martini Cabernet Sauvignon Watercress and Mushroom Salad Wisconsin Blue Cheese Beaulieu Extra Dry Orange Sherbet Ambrosia Cookies Demitasse Entertainment: The Young Columbians (19 Students from the Columbia School of Theatrical Arts, Inc., in Columbia Maryland) In 30 minutes, they cause American History to unfold through classic songs and dances from colonial days to the present. U.S. Marine Band will play selections from American Broadway musicals and movies in the foyer during dinner. U.S. Army Strings will stroll through the Dining Room during dessert. A Marine Corps harpist will provide music in the Diplomatic Reception Room where guests arrive. Prime Minister Rabin of Israel March 7, 1977 Dinner: Cold Cucumber Soup Bread Sticks Baked Stripped Bass Eggplant Braised Celery Charles Krug Johannisberg Riesling Hearts of Palm and Watercress Vinaigrette Almaden Blanc de Blancs Macedoine of Fresh Fruit Macaroons Entertainment: The Alexandria Quartet will perform a brief musical interlude in the Dining Room following the toast. -

American Square Dance Vol. 30, No. 3

A Nf E RICAN SCJURRE ORNCE MARCH 1975 CO-EDITORIfil Political issues have no place on this page, and most have little or no connection with square dancing. The current proposals concerning energy conservation and gas consumption do have a direct bearing on the activity. The controversy stems from gas ra- tioning plans versus higher taxes (pri- Only in a real state of national emer- ces) for gas. Which proposal would be gency should there be a ban on recrea- better for square dancing? It's hard to tion and non-essential businesses. tell, but from where we sit, here's how Let's admit it. Gas rationing will it looks to us. spell disaster for even the "weekend" Take rationing first. If a dancer callers who travel a limited area. It will couple is allotted a certain amount of be catastrophic for "traveling" callers. gas per week, this would be used for Few callers will be able to manage transportation to work and for neces- honestly on the amounts of gas now sary trips first. If both work, or one being proposed for rationing. Dance must travel even a small distance to a bookings will have to be cancelled job, there will be little "extra" gas left outright. for driving to the club dance. The situation if prices are raised If, however, prices are higher per looks slightly better. Callers will pass gallon, but gas is available, economy- along the increased costs of gas in minded dancers will car-pool to events, their fees, and some clubs will not be as well as to work, and there will be able to meet the increases, but some ways to reach that favorite club dance will. -

American Square Dance Vol. 30, No. 7

MED MI 11.• MM. =In ••15. • II1111111,11•11%••••• ••••••••••••Y l'essYeSitil metimmoilillillimi•1111111M111•111111100111111111MEMI marl I I 11111111111111.1111111.111111111.1.1111111.0.1111111111.111111110.1111111.110111Inni -. ---::c.---- --- -- -- : it : iiii ::. ::: • •••• MI •II •• %. .”1: !..4. ...... =WM. MIIIII.. Milli I I 1 ii ii iii Iiii== i0 i := i Ill i u m ii imagumumli mIllhem 11'1111 1 IL ' 11 PHI II 1•11 1111.. 1 1111 I 118 1 III I 1111 limo= mimeo 1111111....16. •1.116111,01J6....J111...1• 1....•1..IILL-....J1.J= J1111111011... - - --- --- •••=IM •-••• •_•-•-•....imm..... ••••••. ii iii 3nssI 33VISIO GL64 Ain r VIII III' . sf1 a.. i , ., I. i AM alb WIIIIIIIIii31111111•11 M1111 IIP•1111 111111111111111,1111116111MINI 11 11111 .1 011111 1111 1111:1111111 IF11111111111111 =mg limn,imil•souniosnimonimr • !RI! soy! !pp Pm imikiapiiiimu •• 4=11•••• •••••14 In the world of fashion, thirty years is a long time. Square dance fashions are no exception, and they Legacy enters, too, into this issue show great changes from the gingham with a resume in Meanderings, and days of long skirts and pantaloons to the photo and resolutions on pages the polyester days of bright colors 28 and 29. Legacy II is history now, and sissy pants. When we asked for and its impact will be felt only as photos to be used in this "distaff" is- the trustees carry its message to local sue, Johnny and Janie Creel served clubs and associations, binding us all up a whole scrapbook of styles (see together (but loosely), with the pur- center spread). Others were sent, too, pose of improving the American and we regret that some could not dance scene for all. -

Section a 5-25-11:Broadsheet

Graduation Edition Potomac Lifestyles Mail or Online Delivery Commemorative Guide — Inside World War II Veterans Honored Subscribe Today! Page 6 Congratulations from Call (304) 530-6397 Local Businesses — Pages 8-11 MOOREFIELD EXAMINER and Hardy County News USPS 362-300 www.moorefieldexaminer.com VOLUME 120 - NUMBER 21 MOOREFIELD, HARDY COUNTY, W.VA., WEDNESDAY, MAY 25, 2011 TWO SECTIONS - 24 PAGES 94¢ Photo by Mike Mallow Enough Rain, Already Photo by Carl Holcomb Sections of Town Run Road in Moorefield was under water after the town received more than 4 inches of rain last week. Other areas of Jade and Rayann Foltz point skyward in memory of their father, Hardy County received between 3 and 5 inches and caused some roads to be swamped. This has been an unusually wet spring and Jason Foltz, after the Region II Championship victory. For details, farmers are challenged to get their fields plowed and planted. see page 1B. Commissioners Approved Space for Day Report Center in HazMat Building By Jean A. Flanagan er area for conferences, for one time. Moorefield Examiner year. Keplinger was also hesitant to re- Teets seconded the motion and linquish the space to the deputies in The Hardy County Commission the motion was approved. August. “We have a lot of projects voted to allow the Day Report Cen- County Clerk Gregg Ely said the planned for that space in terms of ter to occupy an office in the building county would install phone and inter- emergency response,” he told Ward. that houses the Regional Response net service, but the Day Report Cen- Since that time, the commission Vehicle. -

Harvest Sale

PAGE EIGHTEEN - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD, Manchester, Conn., Tues., Oct. 15, 1974 Parking Ban OBITUARIES Begins Nov. 1 The winter parking ban Miss Grace Sowler John R. Goodman Sr. goes into effect again HanrljfHtpr BpralJi Friday, Nov. 1. Miss Grace E. Sowter, 86, of John R. Goodman, 71, of "i FIRE CALLS ) . North Berwick, Maine, died Wethersfield, formerly of 57 If anyone parks their MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 16, 1974 - VOL. XCIV, No. 14 Sunday in a Rochester, N.H., vehicle on any public 'I’iiir t y -t w o pa g e s — t w o se c t io n s Brent Rd., died Sunday at Manchester A City of Village Charm PRICE: FIFTEEN CENTS hospital. Manchester Memorial highway or town owned or ^ r n in Windsor Locks, Miss Hospital. He was the husband of leased off-street parking Sowter had been employed at Mrs. Adeline Carrano Good .’t -. MANCHESTER lot in town between 2 a.m. Monday, 7:09 p.m. — C a ^ - the Travelers Insurance Co., man. and 6 a.m., they will be Hartford, from 1917 to 1955. In Mr. Goodman was born in fire in a field off Rachel Rd. where children were cooking liable to a fine of $5. 1959, she moved to Daytona Hartford and had lived in The ban is meant to keep Beach, Fla., where she lived Florida and Manchester before hot dogs. The fire was put out. Watergate Jury Given the streets clear for snow until five years ago when she moving to Wethersfield. He had But the children returned soon went to North Berwick to make been employed by the U.S. -

Action Is Attraction – There Is No Growth in the Comfort Zone

ACTION IS ATTRACTION – THERE IS NO GROWTH IN THE COMFORT ZONE L’ACTION, C’EST L’ATTRAIT — IL N’Y A PAS DE CROISSANCE DANS LA ZONE DE CONFORT -•- LA ACCIÓN ES ATRACCIÓN — NO HAY CRECIMIENTO EN LA ZONA DE COMODIDAD WORLD SERVICE CONFERENCE SUMMARY WORLD SERVICE 59thWorld Service Annual Conference 2019 2019 ACTION IS ATTR THERE ACTIS NO GROWTHION – AL‑ANON FAMILY GROUPS IN THE COMFORT ZONE 2019 WORLD SERVICE L’ACTION, C’EST L’ATTRAIT — CONFERENCE IL N’Y A PAS DE CROISSANCE DANS LA ZONE DE CONFORT LA ACCIÓN ES- •ATRACCIÓN- — PRE‑CONFERENCE ACTIVITIES NO HAY CRECIMIENTO 2019 Assignments for Selected Committees, EN LA ZONA DE COMODIDAD Thought Forces, and Task Forces ................................................3 Delegate Task Force: Conference Purpose, Makeup, and Roles .........................................................................4 Sharing Area Highlights .....................................................................5 Opening Dinner ...................................................................................7 World59th Service Annual Conference 2019 GENERAL SESSIONS Conference Theme and Opening Remarks .....................................8 Roll Call .................................................................................................9 Seating Motion ..................................................................................10 Welcome from the Board of Trustees ...........................................10 Task Forces for Increased Delegate Participation in the WSC Agenda ..............................................11 -

Trinity Library Title Catalog

Trinity Library Title Catalog Class: Title: Author: 616.8 Ing `End of memory : a natural history of aging and Alzheimer's Ingram, Jay 745 One 101 things to do for Christmas O'Neal, Debbie 745 One c.2 101 things to do for Christmas O'Neal, Debbie Int One 107 questions children ask about prayer Undesignated Pri Ele 11th commandment : wisdom from our children Undesignated Pri Dee 14 cows for America Deedy, Carmen Agra 289.7 Goo 20 most asked questions about the Amish and Mennonites Good, Merle 236.25 Wie 23 questions about hell Wiese, Bill Pri Bre 3 little dassies Brett, Jan 226.5 Luc 3:16 : the numbers of hope Lucado, Max 616.8 Mac 36-hour day : a family guide to caring for persons with Alzheim Mace, Nancy 230.41 Lut 40-Day journey with Martin Luther Luther, Martin Pri Seu 500 hats of Bartholomew Cubbins Seuss, Dr. 364.15 Sla 57 bus Slater, Dashka 248.4 McK 99 1/2 ways to fix your life, labor and love McKinley, Mike Pri Pot 99 plus one Pottebaum, Gerard Pri Mon A is for ark Monroe, Colleen Pri Sti ABC Bible characters Stifle, J.M. Pri Sti ABC Bible stories Stifle, J.M. Pri Sti ABC book about Christmas Stifle, J.M. Pri Sti ABC book about Jesus Stifle, J.M. 220 Abc ABC's of the Bible Undesignated 370.1 Lew Abolition of man Lewis, C. S. 222 Fei Abraham Feiler, Bruce 920 Lin Abraham Lincoln Trueblood, Elton Pri Riv Abraham: Man of Faith Rives, Elsie Int Cre Absolutely normal chaos Creech, Sharon F Ale Absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian Alexie, Sherman 920 Pog Abundance of blessings Pogainis, Ina 1/13/2020 Page 1 of 115 Class: Title: Author: 818.54 Nor Acedia & me Norris, Kathleen Int Hun Across five Aprils Hunt, Irene Int Hun Across five Aprils Hunt, Irene 305.89 Bra Across many mountains Brauer, Yangzom Pri Gre Action Jackson Greenberg, Jan 225.6 Bar Acts of the Apostles Barclay, William Pri Kea Adam Raccoon and the flying machine Keane, Glen Pri Mar Adam, Adam, what do you see? Martin, Bill, Jr. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 7, 2007 No. 39 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was last day’s proceedings and announces the associate pastor at La Verdad Com- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- to the House her approval thereof. munity Baptist Church and is an advo- pore (Ms. MCCOLLUM of Minnesota). Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- cate for people with physical and devel- f nal stands approved. opmental disabilities. f Thank you, Chaplain Wilson, for join- DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER ing us this morning and for serving our PRO TEMPORE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Nation as a Border Patrol agent. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the gentleman from Wisconsin (Mr. SEN- fore the House the following commu- f nication from the Speaker: SENBRENNER) come forward and lead the House in the Pledge of Allegiance. WASHINGTON, DC, Mr. SENSENBRENNER led the ANNOUNCEMENT BY THE SPEAKER March 7, 2007. Pledge of Allegiance as follows: PRO TEMPORE I hereby appoint the Honorable BETTY MCCOLLUM to act as Speaker pro tempore on I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Repub- The SPEAKER pro tempore. After this day. consultation among the Speaker and NANCY PELOSI, lic for which it stands, one nation under God, Speaker of the House of Representatives. indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.