2013 Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Drugs List

^ ^ ^ ^ ^[ ^ The National Drugs List Of Syrian Arab Republic Sexth Edition 2006 ! " # "$ % &'() " # * +$, -. / & 0 /+12 3 4" 5 "$ . "$ 67"5,) 0 " /! !2 4? @ % 88 9 3: " # "$ ;+<=2 – G# H H2 I) – 6( – 65 : A B C "5 : , D )* . J!* HK"3 H"$ T ) 4 B K<) +$ LMA N O 3 4P<B &Q / RS ) H< C4VH /430 / 1988 V W* < C A GQ ") 4V / 1000 / C4VH /820 / 2001 V XX K<# C ,V /500 / 1992 V "!X V /946 / 2004 V Z < C V /914 / 2003 V ) < ] +$, [2 / ,) @# @ S%Q2 J"= [ &<\ @ +$ LMA 1 O \ . S X '( ^ & M_ `AB @ &' 3 4" + @ V= 4 )\ " : N " # "$ 6 ) G" 3Q + a C G /<"B d3: C K7 e , fM 4 Q b"$ " < $\ c"7: 5) G . HHH3Q J # Hg ' V"h 6< G* H5 !" # $%" & $' ,* ( )* + 2 ا اوا ادو +% 5 j 2 i1 6 B J' 6<X " 6"[ i2 "$ "< * i3 10 6 i4 11 6! ^ i5 13 6<X "!# * i6 15 7 G!, 6 - k 24"$d dl ?K V *4V h 63[46 ' i8 19 Adl 20 "( 2 i9 20 G Q) 6 i10 20 a 6 m[, 6 i11 21 ?K V $n i12 21 "% * i13 23 b+ 6 i14 23 oe C * i15 24 !, 2 6\ i16 25 C V pq * i17 26 ( S 6) 1, ++ &"r i19 3 +% 27 G 6 ""% i19 28 ^ Ks 2 i20 31 % Ks 2 i21 32 s * i22 35 " " * i23 37 "$ * i24 38 6" i25 39 V t h Gu* v!* 2 i26 39 ( 2 i27 40 B w< Ks 2 i28 40 d C &"r i29 42 "' 6 i30 42 " * i31 42 ":< * i32 5 ./ 0" -33 4 : ANAESTHETICS $ 1 2 -1 :GENERAL ANAESTHETICS AND OXYGEN 4 $1 2 2- ATRACURIUM BESYLATE DROPERIDOL ETHER FENTANYL HALOTHANE ISOFLURANE KETAMINE HCL NITROUS OXIDE OXYGEN PROPOFOL REMIFENTANIL SEVOFLURANE SUFENTANIL THIOPENTAL :LOCAL ANAESTHETICS !67$1 2 -5 AMYLEINE HCL=AMYLOCAINE ARTICAINE BENZOCAINE BUPIVACAINE CINCHOCAINE LIDOCAINE MEPIVACAINE OXETHAZAINE PRAMOXINE PRILOCAINE PREOPERATIVE MEDICATION & SEDATION FOR 9*: ;< " 2 -8 : : SHORT -TERM PROCEDURES ATROPINE DIAZEPAM INJ. -

Vaginal Yeast Infections Yeast Are Caused Byinfection an Overgrowth of Yeast in the Vagina

•Vaginal Yeast infections Yeast are caused byInfection an overgrowth of yeast in the vagina. • Yeast infections can be treated with over-the-counter medications. • Many yeast infections can be treated without seeing a medical provider. Symptoms: • Vaginal Itching, burning, swelling • Vaginal discharge (thick white vaginal discharge that looks like cottage cheese and does not have a bad smell) • May have pain during sex • May be worse the week before your period Self-care measures: • Use an over-the-counter medication for vaginal yeast infections. These antifungal medications should contain butoconazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, or tioconazole and should be used for 3-7 days. Follow directions on medication insert. Note: Over-the-counter medications are available at the University Health Center Pharmacy (first floor of Student Success Center), local pharmacies, grocery stores and superstores (examples - Walmart or Target). • Change tampons, pads and panty liners often • Do wear underwear with a cotton crotch • Apply a cool compress to labia for comfort • Do not douche or use vaginal sprays • Do not wear tight underwear and do not wear underwear to sleep • Avoid hot tubs Limit spread to others: • It is possible to spread yeast infections to your partner(s) during vaginal, oral or anal sex. • If your partner is a male, the risk is low. Some men get an itchy rash on their penis. • If this happens have your partner see a medical provider. • If your partner is a female, you may spread the yeast infection to her. • She should be treated if she -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

Crux 93 MAY-JUN 2019.Cdr

VOLUME - XVI ISSUE - XCIII MAY/JUN 2019 Vaginitis, also known as vulvovaginitis, is inflammation of the vagina and vulva. Symptoms may include itching, burning, pain, discharge, and a bad smell. Certain types of vaginitis may result in complications during pregnancy. 1 Editorial The three main causes are infections, specifically bacterial vaginosis, vaginal yeast Disease infection, and trichomoniasis. Other causes include allergies to substances such as 2 spermicides or soaps or as a result of low estrogen levels during breast-feeding or Diagnosis after menopause. More than one cause may exist at a time. The common causes 8 Interpretation vary by age. Diagnosis generally include examination, measuring the pH, and culturing the discharge. Other causes of symptoms such as inflammation of the cervix, pelvic Troubleshooting 13 inflammatory disease, cancer, foreign bodies, and skin conditions should be ruled out. 15 Bouquet Treatment depends on the underlying cause. Infections should be treated. Sitz baths may help with symptoms. Soaps and feminine hygiene products such as 16 Tulip News sprays should not be used. About a third of women have vaginitis at some point in time. Women of reproductive age are most often affected. The “DISEASE DIAGNOSIS” segment delves deep into the various CLINOCODIAGNOSTIC aspects of Vaginitis. “INTERPRETATION” portion highlights a very common disorder termed as BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS. Though not dangerous in itself, it predisposes to other sinister STDs. What we are discussing in “INTERPRETATION” is all about bacteria and the Primary investigation when t dealing with bacteria is GRAM's STAIN. Hence “TROUBLESHOOTING” part of this issue discusses GRAM's STAIN. What can possibly go wrong, how to identify and thereafter rectify the issues involved. -

Guidelines for the Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS 3. TREATMENT OF SPECIFIC INFECTIONS 3.1. GONOCOCCAL INFECTIONS A large proportion of gonococcal isolates worldwide are now resistant to penicillins, tetracyclines, and other older antimicrobial agents, which can therefore no longer be 32 recommended for the treatment of gonorrhoea. TREATMENT OF SPECIFIC INFECTIONS SPECIFIC OF TREATMENT It is important to monitor local in vitro susceptibility,as well as the clinical efficacy of recommended regimens. Note In general it is recommended that concurrent anti-chlamydia therapy be given to all patients with gonorrhoea, as described in the section on chlamydia infections, since dual infection is common.This does not apply to patients in whom a specific diagnosis of C. trachomatis has been excluded by a laboratory test. UNCOMPLICATED ANOGENITAL INFECTION Recommended regimens I ciprofloxacin, 500 mg orally,as a single dose OR I azithromycin, 2 g orally,as a single dose OR I ceftriaxone, 125 mg by intramuscular injection, as a single dose OR I cefixime, 400 mg orally,as a single dose OR I spectinomycin, 2 g by intramuscular injection, as a single dose. Note I Ciprofloxacin is contraindicated in pregnancy.The manufacturer does not recommend it for use in children and adolescents. GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS I There is accumulating evidence that the cure rate of Azithromycin for gonococcal infections is best achieved by a 2-gram single dose regime.The 1-gram dose provides protracted sub-therapeutic levels which may precipitate the emergence of resistance. There are variations in the anti-gonococcal activity of individual quinolones, and it is important to use only the most active. -

Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports / Vol. 70 / No. 4 July 23, 2021 Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations and Reports CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Methods ....................................................................................................................1 Clinical Prevention Guidance ............................................................................2 STI Detection Among Special Populations ............................................... 11 HIV Infection ......................................................................................................... 24 Diseases Characterized by Genital, Anal, or Perianal Ulcers ............... 27 Syphilis ................................................................................................................... 39 Management of Persons Who Have a History of Penicillin Allergy .. 56 Diseases Characterized by Urethritis and Cervicitis ............................... 60 Chlamydial Infections ....................................................................................... 65 Gonococcal Infections ...................................................................................... 71 Mycoplasma genitalium .................................................................................... 80 Diseases Characterized -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports / Vol. 64 / No. 3 June 5, 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations and Reports CONTENTS CONTENTS (Continued) Introduction ............................................................................................................1 Gonococcal Infections ...................................................................................... 60 Methods ....................................................................................................................1 Diseases Characterized by Vaginal Discharge .......................................... 69 Clinical Prevention Guidance ............................................................................2 Bacterial Vaginosis .......................................................................................... 69 Special Populations ..............................................................................................9 Trichomoniasis ................................................................................................. 72 Emerging Issues .................................................................................................. 17 Vulvovaginal Candidiasis ............................................................................. 75 Hepatitis C ......................................................................................................... 17 Pelvic Inflammatory -

Treatment of Recurrent Vulvo-Vaginal Candidiasis with Sustained-Release Butoconazole Pessary

C ase R eport Singapore Med J 2012; 53(12) : e269 Treatment of recurrent vulvo-vaginal candidiasis with sustained-release butoconazole pessary Ling Zhi Heng1, MBBS, Yujia Chen1, MBBS, Thiam Chye Tan1,2, MBBS, MMed ABSTRACT Vulvo-vaginal candidiasis (VVC) is a common infection among women. 5% of women with acute infection experience recurrent vulvo-vaginal candidiasis (RVVC). There is currently no optimal or recommended regime for RVVC. Although antifungal agents, such as imidazoles, have been successfully used as a first-line treatment for acute VVC, its effectiveness is limited in RVVC. This could be due to patient factors, drug application (such as leakage) or dosing factors. A sustained-release (SR) bioadhesive vaginal cream (2% butoconazole nitrate) has incorporated VagiSite technology, a topical drug delivery system that allows SR of the drug. We describe its efficacy and the successful use of a butoconazole-SR formulation in the treatment of two cases of RVVC. Keywords: butoconazole, candidiasis, recurrent vulvo-vaginal Singapore Med J 2012; 53(12): e269–e271 INTRODUCTION Table I. Risk factors for recurrent vulvo-vaginal candidiasis. Candidiasis is a common cause of infective vaginal discharge Risk factors Examples experienced by women. 75% of women experience at least Microbial • Candida albicans species one episode of vaginitis during their lifetime. Recurrent vulvo- • Non-albicans Candida species vaginal candidiasis (RVVC) is defined as four or more episodes Host • Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus • Oestrogen excess – oral contraceptive pills, hormone of symptomatic vulvo-vaginal cadidiasis (VVC) in one year. Up replacement therapy, local oestrogen administration, to 5% of women of childbearing age have experienced RVVC.(1) pregnancy Common symptoms include vaginal discharge, vulvar pruritus, • Antibiotic-induced dyspareunia and dysuria. -

A Comparison of Butoconazole Nitrate Cream with Econazole Nitrate Cream for the Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

The Journal ofInternational Medical Research 1990; 18: 389 - 399 A Comparison of Butoconazole Nitrate Cream with Econazole Nitrate Cream for the Treatment of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis 2 H. RuCI and M. Vitse 'Belle de Mai Maternity Hospital, Marseille, France; 2Gynaecology and Obstetrics Clinic, Amiens, France In a randomized, single-blind, parallel study the safety and efficacy of 2% butoconazole nitrate cream used for 3 days were compared with those of 1% econazole nitrate cream used for 7 days at night in patients with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Patients in both treatment groups had positive potassium hydroxide smears and fungal cultures, and were similar in age, disease duration and history, obstetric history and contraceptive use. Of the 75 patients enrolled, 63 with a Candida albicans infection were included in the efficacy analyses. Evaluations were made at the start of the study (visit 1), after 10 - 23 days (visit 2) and after 24 - 45 days (visit 3). Both drugs significantly reduced all signs and symptoms, and at visits 2 and 3 the percentages of patients considered microbiologically, clinically and therapeutically cured were consistently higher for butoconazole- than for econazole-treated patients, although differences were not statistically different. Al though both drugs were safe and well tolerated, it is concluded that butoconazole because of its much shorter regimen and superior clini cal and microbiological performance was the drug of choice. Lors d'une etude parallele randomisee en simple aveugle, I'Innoculte et I'efflcacite du nitrate de butoconazole creme a2% applique pendant 3 jours ont ete comparees acelles du nitrate d'econazole creme a 1% administre la nuit pendant 7 jours a des patientes presentant une candidose vulvo-vaginale. -

Treatment of Vaginitis Caused by Candida Glabrata: Use of Topical Boric Acid and Flucytosine

Treatment of vaginitis caused by Candida glabrata: Use of topical boric acid and flucytosine Jack D. Sobel, MD,a Walter Chaim, MD,b Viji Nagappan, MD,a and Deborah Leaman, RN, BSNa Detroit, Mich, and Beer Sheva, Israel OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to review the treatment outcome and safety of topical therapy with boric acid and flucytosine in women with Candida glabrata vaginitis. STUDY DESIGN: This was a retrospective review of case records of 141 women with positive vaginal cultures of C glabrata at two sites, Wayne State University School of Medicine and Ben Gurion University. RESULTS: The boric acid regimen, 600 mg daily for 2 to 3 weeks, achieved clinical and mycologic success in 47 of 73 symptomatic women (64%) in Detroit and 27 of 38 symptomatic women (71%) in Beer Sheba. No advantage was observed in extending therapy for 14 to 21 days. Topical flucytosine cream administered nightly for 14 days was associated with a successful outcome in 27 of 30 of women (90%) whose condition had failed to respond to boric acid and azole therapy. Local side effects were uncommon with both regimens. CONCLUSIONS: Topical boric acid and flucytosine are useful additions to therapy for women with azole- refractory C glabrata vaginitis. (Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1297-300.) Key words: Vaginitis, Candida glabrata, boric acid, flucytosine The increased use of vaginal cultures in the treatment Candida vaginitis studies have been insufficient to allow of women with chronic recurrent or relapsing vaginitis has separate consideration.6,7 Accordingly, practitioners have provided clinicians with new insights into the Candida been provided with relatively poor information regarding microorganisms that are responsible for yeast vaginitis. -

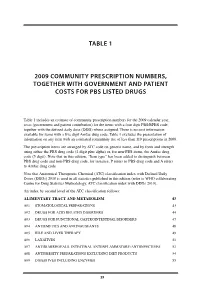

Table 1 2009 Community Prescription Numbers

TABLE 1 2009 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS LISTED DRUGS Table 1 includes an estimate of community prescription numbers for the 2009 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 excludes the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2009. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit plus alpha) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Note that in this edition, “Item type” has been added to distinguish between PBS drug code and non-PBS drug code, for instance, P refers to PBS drug code and A refers to Amfac drug code. Note that Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2010 is used in all statistics published in this edition (refer to WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs 2010). An index by second level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 43 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 43 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 44 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 47 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 48 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 49 A06 LAXATIVES 51 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVES