Msc Shipping Registration Adal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification of Icelandic Watersheds and Rivers to Explain Life History Strategies of Atlantic Salmon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Siaurdur Gudjonsson for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fisheries Science presented on May 17, 1990. Title: Classification of Icelandic Watersheds and Rivers to Explain Life History Strategies of Atlantic Salmon Abstract approved: 4 Redacted for Privacy Charles E. Warren A hierarchical classification system of Iceland's watersheds and rivers is presented. The classification is based on Iceland's substrate, climate, water, biota, and human cultural influences. The geological formations of Iceland are very different in character depending on their age and formation history. Three major types of formations occur: Tertiary, Plio-Pleistocene, and Pleistocene. These formations have different hydrological characters and different landscapes. There are also large differences in the climate within Iceland. Four major river types are found in Iceland: spring-fed rivers in Pleistocene areas, direct runoff rivers in Plio-Pleistocene areas, direct runoff rivers in Tertiary areas and wetland heath rivers in Tertiary areas. Eleven biogeoclimatic regions occur in Iceland, each having a different watershed type. The classification together with life history theory can explain the distributions, abundances, and life history strategies of Icelandic salmonids. Oceanic conditions must also be considered to explain the life history patterns of anadromous populations. When the freshwater and marine habitat is stable, the life history patterns of individuals in a population tend to be uniform, one life history form being most common. In an unstable environment many life history forms occur and the life span of one generation is long. The properties of the habitat can further explain which life history types are present. -

ICELAND Journey to Iceland and Explore How Its Geography Helped Shape Its Unique Culture and Its Independence from Fossil Fuels

Faces® Teacher Guide: November/December 2018 ICELAND Journey to Iceland and explore how its geography helped shape its unique culture and its independence from fossil fuels. CONVERSATION QUESTION How does Iceland’s geography influence its culture? In addition to supplemental materials TEACHING OBJECTIVES focused on core Social Studies skills, • Students will learn about Icelandic geography and this flexible teaching tool offers culture. vocabulary-building activities, • Students will describe how the physical characteristics of places are connected to human questions for discussion, and cross- cultures. curricular activities. • Students will analyze the combinations of cultural and environmental characteristics that make places different from other places. • Students will explain how cultural patterns and economic decisions influence environments and the SELECTIONS daily lives of people. • In the Kitchens of Fire and Ice • Students will use details from a text to write a story. Expository Nonfiction, ~1150L • Students will conduct research using print and digital • Weathering the Weather sources. Expository Nonfiction, ~1150L • Students will create a multimedia presentation. • The Eco-Friendliest Country on Earth Expository Nonfiction, ~1150L U33T http://www.cricketmedia.com/classroom/Faces-magazine Faces® Teacher Guide: November/December 2018 In the Kitchens of Fire and ENGAGE Ice Conversation Question: How does Iceland’s geography influence its culture? pp. 12–15, Expository Nonfiction Explore how the rugged geography and Explain that Iceland’s geography is dominated by rocky soil and climate of Iceland have influenced its mountainous terrain with many active volcanoes. Also explain it is an farming practices and its cuisine. island in the far north, near the Arctic Circle. Ask students to hypothesize how the geography of Iceland influences the types of foods that are commonly eaten there. -

Pilgrims to Thule

MARBURG JOURNAL OF RELIGION, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2020) 1 Pilgrims to Thule: Religion and the Supernatural in Travel Literature about Iceland Matthias Egeler Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Abstract The depiction of religion, spirituality, and/or the ‘supernatural’ in travel writing, and more generally interconnections between religion and tourism, form a broad and growing field of research in the study of religions. This contribution presents the first study in this field that tackles tourism in and travel writing about Iceland. Using three contrasting pairs of German and English travelogues from the 1890s, the 1930s, and the 2010s, it illustrates a number of shared trends in the treatment of religion, religious history, and the supernatural in German and English travel writing about Iceland, as well as a shift that happened in recent decades, where the interests of travel writers seem to have undergone a marked change and Iceland appears to have turned from a land of ancient Northern mythology into a country ‘where people still believe in elves’. The article tentatively correlates this shift with a change in the Icelandic self-representation, highlights a number of questions arising from both this shift and its seeming correlation with Icelandic strategies of tourism marketing, and notes a number of perspectives in which Iceland can be a highly relevant topic for the research field of religion and tourism. Introduction England and Germany have long shared a deep fascination with Iceland. In spite of Iceland’s location far out in the North Atlantic and the comparative inaccessibility that this entailed, travellers wealthy enough to afford the long overseas passage started flocking to the country even in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

Autumn 1997 of Proportional Representation for a Term of Four Years

The Economy of Iceland CENTRAL BANK OF ICELAND The Economy of Iceland October 1997 Published semi-annually by the International Department of the Central Bank of Iceland, 150 Reykjavík, Iceland ISSN 1024 - 0039 REPUBLIC OF ICELAND People Population.......................................269,735 (December 1, 1996) Capital.............................................Reykjavík, 105,487 (December 1, 1996) Language........................................Icelandic; belongs to the Nordic group of Germanic languages Religion...........................................Evangelical Lutheran (95%) Life expectancy...............................Females: 81 years , Males: 75 years Governmental System Government ....................................Constitutional republic Suffrage ..........................................Universal, over 18 years of age Legislature ......................................Alþingi (Althing); 63 members Election term...................................Four years Economy Monetary unit ..................................Króna (plural: krónur); currency code: ISK Gross domestic product..................487 billion krónur (US$ 7.3 billion) in 1996 International trade...........................Exports 36% and imports 36% of GDP in 1996 Per capita GDP...............................1,760 thousand krónur (US$ 26.900) in 1996 Land Geographic size..............................103,000 km2 (39,768 mi2) Highest point...................................2,119 m (6,952 ft) Exclusive economic zone ...............200 nautical miles (758,000 km2 -

34 Iceland As an Imaginary Place in a European

ICELAND AS AN IMAGINARY PLACE IN A EUROPEAN CONTEXT – SOME LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS Sveinn Yngvi Egilsson University of Iceland [email protected] Abstract The article focuses on the image of Iceland and Iceland as an imaginary place in literature from the nineteenth century onwards. It is especially concerned with the aesthetics or discourse of the sublime, claiming that it is the common denominator in many literary images of Iceland. The main proponents of this aesthetics or discourse in nineteenth-century Icelandic literature are discussed before pointing to further developments in later times. Among those studied are the nineteenth-century poets Bjarni Thorarensen (1786-1841), Jónas Hallgrímsson (1807- 1845), Grímur Thomsen (1820-1896) and Steingrímur Thorsteinsson (1831-1913), along with a number of contemporary Icelandic writers. Other literary discourses also come into play, such as representing Iceland as "the Hellas of the North", with the pastoral mode or discourse proving to have a lasting appeal to Icelandic writers and often featuring as the opposite of the sublime in literary descriptions of Iceland. Keywords Icelandic literature, Romantic poetry; the discourse of the sublime, the idea of the North; pastoral literature. This article will focus on the image of Iceland and on Iceland as an imaginary place in literature from the nineteenth century onwards. It will especially be concerned with the aesthetics of the sublime, claiming that it is the common denominator in many literary images of Iceland. The main proponents of this aesthetics in nineteenth-century Icelandic literature are discussed before pointing to further developments in later times. By looking at a number of literary works from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, it is suggested that this aesthetics can be seen to continue in altered form into the present day. -

October 2017 President's Message by Meshon Rawls “Why Are You Here? More Page

Volume 77, No. 2 Eighth Judicial Circuit Bar Association, Inc. October 2017 President's Message By Meshon Rawls “Why are you here? More page. I am an African-American woman with a colorful importantly, why are each of life story – a story filled with experiences that have us lawyers? Why is not only a prepared me for this very moment. Unfortunately, critical question for each of us; the demands of the profession have a way of why is also a critical question overshadowing the essence of who we are. So, what for the Florida Bar.” These were do we do? I suggest we take heed to the words of the words of Michael Higer, the wisdom shared by Chester Chance, a retired Judge in President of the Florida Bar, as the Eighth Circuit. In his introduction of Charlie Carter, he elaborated on the mission the recipient of the 2016 Tomlinson Award, Judge of the Florida Bar during his Chance spoke of the times when lawyers would get swearing in speech in June. As I together after work. As I listened, I envisioned getting considered his questions, I found myself reassessing to know those who I often see, but never seem to find the mission of the Eighth Judicial Circuit Bar the time to have an in-depth conversation with - to Association (EJCBA). What is our why? The mission hear their stories, to acknowledge their perspective, of the EJCBA is to assist attorneys in the practice to appreciate their similarities and differences. of law and in their service to the judicial system To address this issue, I suggest we take and their clients and their community. -

Marla J. Koberstein

Master‘s thesis Expansion of the brown shrimp Crangon crangon L. onto juvenile plaice Pleuronectes platessa L. nursery habitat in the Westfjords of Iceland Marla J. Koberstein Advisor: Jόnas Páll Jόnasson University of Akureyri Faculty of Business and Science University Centre of the Westfjords Master of Resource Management: Coastal and Marine Management Ísafjörður, February 2013 Supervisory Committee Advisor: Name, title Reader: Name, title Program Director: Dagný Arnarsdóttir, MSc. Marla Koberstein Expansion of the brown shrimp Crangon crangon L. onto juvenile plaice Pleuronectes platessa L. nursery habitat in the Westfjords of Iceland 45 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Master of Resource Management degree in Coastal and Marine Management at the University Centre of the Westfjords, Suðurgata 12, 400 Ísafjörður, Iceland Degree accredited by the University of Akureyri, Faculty of Business and Science, Borgir, 600 Akureyri, Iceland Copyright © 2013 Marla Koberstein All rights reserved Printing: Háskólaprent, Reykjavik, February 2013 Declaration I hereby confirm that I am the sole author of this thesis and it is a product of my own academic research. __________________________________________ Student‘s name Abstract Sandy-bottom coastal ecosystems provide integral nursery habitat for juvenile fishes, and threats to these regions compromise populations at this critical life stage. The threat of aquatic invasive species in particular can be difficult to detect, and climate change may facilitate the spread and establishment of new species. In 2003, the European brown shrimp Crangon crangon L. was discovered off the southwest coast of Iceland. This species is a concern for Iceland due to the combination of its dominance in coastal communities and level of predation on juvenile flatfish, namely plaice Pleuronectes platessa L., observed in its native range. -

Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland

Hugvísindasvið Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland: th From the Period of Settlement to the 12 Century Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Andrew Umbrich September 2012 U m b r i c h | 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Early Religious Practice in Norse Greenland: th From the Period of Settlement to the 12 Century Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Andrew Umbrich Kt.: 130388-4269 Leiðbeinandi: Gísli Sigurðsson September 2012 U m b r i c h | 3 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Scholarly Works and Sources Used in This Study ...................................................... 8 1.2 Inherent Problems with This Study: Written Sources and Archaeology .................... 9 1.3 Origin of Greenland Settlers and Greenlandic Law .................................................. 10 2.0 Historiography ................................................................................................................. 12 2.1 Lesley Abrams’ Early Religious Practice in the Greenland Settlement.................... 12 2.2 Jonathan Grove’s The Place of Greenland in Medieval Icelandic Saga Narratives.. 14 2.3 Gísli Sigurðsson’s Greenland in the Sagas of Icelanders: What Did the Writers Know - And How Did They Know It? and The Medieval Icelandic Saga and Oral Tradition: A Discourse on Method....................................................................................... 15 2.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ -

Elements of Nature Relocated the Work of Studio Granda

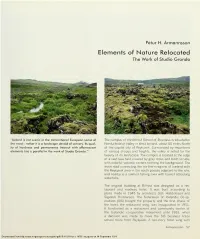

Petur H. Armannsson Elements of Nature Relocated The Work of Studio Granda "Iceland is not scenic in the conventional European sense of The campus of the Bifrost School of Business is situated in the word - rather it is a landscape devoid of scenery. Its qual- Nordurardalur Valley in West Iceland, about 60 miles North ity of hardness and permanence intercut v/\1\-i effervescent of the capital city of Reykjavik. Surrounded by mountains elements has a parallel in the work of Studio Granda/" of various shapes and heights, the valley is noted for the beauty of its landscape. The campus is located at the edge of a vast lava field covered by gray moss and birch scrubs, w/ith colorful volcanic craters forming the background. The main road connecting the northern regions of Iceland with the Reykjavik area in the south passes adjacent to the site, and nearby is a salmon-fishing river with tourist attracting waterfalls. The original building at Bifrost was designed as a res- taurant and roadway hotel. It was built according to plans made in 1945 by architects Gisli Halldorsson and Sigvaldi Thordarson. The Federation of Icelandic Co-op- eratives (SIS) bought the property and the first phase of the hotel, the restaurant wing, was inaugurated in 1951. It functioned as a restaurant and community center of the Icelandic co-operative movement until 1955, when a decision was made to move the SIS business trade school there from Reykjavik. A two-story hotel wing with Armannsson 57 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/thld_a_00361 by guest on 24 September 2021 hotel rooms was completed that same year and used as In subsequent projects, Studio Granda has continued to a student dormitory in the winter. -

Pocket Reykjavik 1

REYKJAVĺK TOP EXPERIENCES • LOCAL LIFE • MADE EASY Alexis Averbuck 00--title-contents-pk-rey1.inddtitle-contents-pk-rey1.indd 1 115/01/20155/01/2015 112:09:092:09:09 PM In This Book 16 Need to Know 17 18 Neighbourhoods 19 Before You Go Arriving in Getting Around QuickStart Reykjavík Laugavegur & Skólavörðustígur Need to Iceland’s primary international airport, Kefla- A car is unnecessary in central Reykjavík as Reykjaví k & Around Your Daily Budget (p48) vík International Airport (KEF) is 48km west it’s so easy to explore on foot and by bus. Laugavegur is Reykjavík’s of Reykjavík, on the Reykjanes Peninsula. Car and camper hire are best for countryside Know Budget less than Ikr20,000 Neighbourhoods premier shopping street Frequent, convenient buses serve central excursions. X Dorm bed Ikr4000–7000 and centre for cool cafes, Reykjavík. Golden Circle West Iceland For more information, X Grill-bar grub/soup lunch Ikr1200–1800 J Local Bus bars and restaurants. (p74) (p102) From KeÁ avík International Its arty cousin Skóla- E see Survival Guide (p137) X Golden Circle bus pass Ikr8500 A Strætó (%540 2700; www.straeto.is) oper- Whale Top Experiences E Top Experiences Airport vörðustígur leads to ates regular, easy buses around Reykjavík and Watching famous Hallgrímskirkja. Þingvellir Settlement Centre Currency Midrange Ikr20,000–35,000 Bus Flybus (%580 5400; www.re.is; W), its suburbs; it also operates long-distance # E E Top Experiences Geysir Icelandic króna (Ikr) X Guesthouse double room Ikr17,000–25,000 Airport Express (%540 1313; www.air- buses (p141). It has online schedules, a Snæfellsjökull Hallgrímskirkja Gullfoss National Park X Cafe meal Ikr1800–3000 portexpress.is; W) and discount operator smartphone app and a route book for sale Language K-Express (%823 0099; www.kexpress. -

Flags of the World

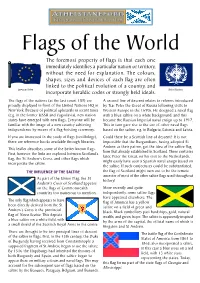

ATHELSTANEFORD A SOME WELL KNOWN FLAGS Birthplace of Scotland’s Flag The name Japan means “The Land Canada, prior to 1965 used the of the Rising Sun” and this is British Red Ensign with the represented in the flag. The redness Canadian arms, though this was of the disc denotes passion and unpopular with the French sincerity and the whiteness Canadians. The country’s new flag represents honesty and purity. breaks all previous links. The maple leaf is the Another of the most famous flags Flags of the World traditional emblem of Canada, the white represents in the world is the flag of France, The foremost property of flags is that each one the vast snowy areas in the north, and the two red stripes which dates back to the represent the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. immediately identifies a particular nation or territory, revolution of 1789. The tricolour, The flag of the United States of America, the ‘Stars and comprising three vertical stripes, without the need for explanation. The colours, Stripes’, is one of the most recognisable flags is said to represent liberty, shapes, sizes and devices of each flag are often in the world. It was first adopted in 1777 equality and fraternity - the basis of the republican ideal. linked to the political evolution of a country, and during the War of Independence. The flag of Germany, as with many European Union United Nations The stars on the blue canton incorporate heraldic codes or strongly held ideals. European flags, is based on three represent the 50 states, and the horizontal stripes. -

Hunting Reindeer in East Iceland

Master’s Thesis Hunting Reindeer in East Iceland The Economic Impact Stefán Sigurðsson Supervisors: Vífill Karlsson Kjartan Ólafsson University of Akureyri School of Business and Science February 2012 Acknowledgements The parties listed below are thanked for their contribution to this thesis. Vífill Karlsson, consultant and assistant professor, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, for his patience and outstanding work as supervisor. Kjartan Ólafsson, lecturer, faculty of humanities and social sciences, University of Akureyri, for his work and comments as supervisor. Guðmundur Kristján Óskarsson, lecturer, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, for his assistance when processing statistics. Jón Þorvaldur Heiðarsson, lecturer, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, and researcher, Research Center University of Akureyri, for his comments. Ögmundur Knútsson, lecturer, department of business administration, University of Akureyri, for his comments. Steinar Rafn Beck, advisor, department of natural resource sciences, for valuable information when working on this master thesis. Bjarni Pálsson, divisional manager, Department for natural resource sciences, for valuable information when working on this master thesis. Rafn Kjartansson, translator and language reviewer of this work. Astrid Margrét Magnúsdóttir, director of Information Services, University of Akureyri, for her comments on documentation and references. ---------------------------------------------------------- Stefán Sigurðsson ii Abstract Tourism in Iceland is of great importance and ever-growing. During the period 2000- 2008 the share of tourism in GDP was 4.3% to 5.7%. One aspect of the tourist industry is hunting tourism, upon which limited research has been done and only fragmented information exists on the subject. The aim of this thesis is to estimate the economic impact of reindeer hunting on the hunting area.