Global Political Thought B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophical Study of Iqbal's Thought

Teosofia: Indonesian Journal of Islamic Mysticism, Volume 6, Number 1, 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21580/tos.v6i1.1698 THE PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY OF IQBAL’S THOUGHT: The Mystical Experience and the Negation of The Self-Negating Quietism Alim Roswantoro UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta [email protected] Abstract The article tries to philosophically explore the Iqbal’s notion of mysticism and the mystic’s attitude in facing the world life. The exploration is focused on his concept of mystical experience and the negation of the self-negating quietism. And from this conception, this writing efforts to withdraw the implication to the passive-active attitude of the worldly life. It is the philosophical understanding of the Islamic mysticism in Iqbal’s philosophy as can be traced and found out in his works, particularly in his magnum opus, ‚The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam‛. Mysticism, in Iqbal’s understanding, is the human inner world in capturing reality as a whole or non- serial time reality behind his encounter with the Ultimate Ego. For him, there are two experiences, that is, normal one and mystical one. In efforts to understand mysticism, one has to have deep understanding of the basic characters of human mystical experience that is very unique in nature compared to human normal one. Keywords: mystical experience, self-negation, active selfness, making fresh world A. Introduction he great Urdu poet-philosopher, Muhammad Iqbal, influenced the religious thought of the Muslims not only in Pakistan and India, but also in Europe, Asia, and Africa T in many ways. -

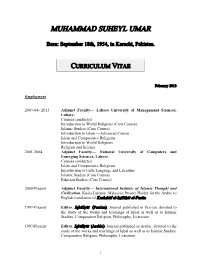

Muhammad Suheyl Umar

MUHAMMAD SUHEYL UMAR Born: September 18th, 1954, in Karachi, Pakistan. CURRICULUM VITAE February 2013 Employment 2003-04– 2013 Adjunct Faculty— Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore. Courses conducted: Introduction to World Religions (Core Course) Islamic Studies (Core Course) Introduction to Islam —Advanced Course Islam and Comparative Religions Introduction to World Religions Religion and Science 2001-2004 Adjunct Faculty— National University of Computers and Emerging Sciences, Lahore. Courses conducted: Islam and Comparative Religions Introduction to Urdu Language and Literature Islamic Studies (Core Course) Pakistan Studies (Core Course) 2000-Present Adjunct Faculty— International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Project Holder for the Arabic to English translation of Kashsh«f al-IÄÇil«Á«t al-Funën. 1997-Present Editor, Iqb«liy«t (Persian); Journal published in Persian, devoted to the study of the works and teachings of Iqbal as well as to Islamic Studies, Comparative Religion, Philosophy, Literature. 1997-Present Editor, Iqb«liy«t (Arabic); Journal published in Arabic, devoted to the study of the works and teachings of Iqbal as well as to Islamic Studies, Comparative Religion, Philosophy, Literature. 1 1997-Present Director, Iqbal Academy Pakistan, a government research institution for the works and teachings of Iqbal, the poet Philosopher of Pakistan who is the main cultural force and an important factor in the socio- political dynamics of the people of the Sub-continent. 1997-Present Editor, Iqbal Review, Iqb«liy«t; Quarterly Journals, published alternately in Urdu and English, devoted to the study of the works and teachings of Iqbal as well as to Islamic Studies, Comparative Religion, Philosophy, Literature, History, Arts and Sociology. -

Studying Muhammad Iqbal's Works in Azerbaijan

Studying Muhammad Iqbal’s Works in Azerbaijan 65 Studying Muhammad Iqbal’s Works in Azerbaijan Dr. Basira Azizaliyeva* Abstract Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938) was Pakistan‘s prominent poet, philosopher and Islamic scholar. His works are characterized by a number of essential features. Islam, love philosophy, perfect humans were expressed in unity, in Iqbal‘s worldview. Iqbal performed as an advocate of humanism, global peace and cordial relations between East and West based on peaceful and tolerant values. He awakened the Muslims‘ material-spiritual development in the 20th century. Having a special propensity for Sufism, the writer was enriched and inspired by the work of the great Turkic Sufi thinker and poet Mevlana Jalāl Ad Dīn Rūmī. Muhammad Iqbal acted as a poet, philosopher, lawyer and teacher. Illuminator and reformer M. Iqbal, who was politically active, also gave concept for the establishment of the state of Indian Muslims in north-western India. The human factor is the main subject of M. Iqbal's thinking. The poet-thinker perceived Islamic society, as well as human pride as the centrifugal force of the whole world, and considered creative and moral relations as an important factor in solving the problems of human society. The questions that Iqbal adopted on the social and philosophical thinking of the East and the West were also directed to this important problem. M. Iqbal spoke from the position of the Islamic religion and at the same time correctly assessed the role of Islam in the modern world, and also invited the Islamic world to develop science and education. This article highlights number of research studies accomplished in Azerbaijan on poetry and philosophical works of Muhammad Iqbal. -

Dr. Allama Iqbal Tehreek-E Mashraqia, and Germany Dr

DR. ALLAMA IQBAL TEHREEK-E MASHRAQIA, AND GERMANY DR. ABIDA IQBAL1,SARTAJ MANZOOR PARRAY2, DR KRANTI VATS3 ABSTRACT The modeler of Pakistan and an observed Muslim Philosopher, Theologian, and Mystic Poet, Dr. Allama Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1838) lived in British India. Around then Subcontinent was under the oppression of British pilgrim masters. He got his Ph.D. Degree from the Munch University of Germany in 1907. The point of his doctoral postulation in Germany was as under: "The Development of Metaphysics in Persia". Dr. Muhammad Iqbal was a flexible identity. He had a capability in different dialects like English, Urdu, Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, Punjabi and German. He improved his idea by concentrate antiquated and Modern thinkers, artists, sages and essayists of the East and the West. He refreshed his insight with the logical progressions of his chance too. In spite of the fact that there were different points of Allama Dr. Muhammad Iqbal's advantage yet the themes like Iran, Persian Literature and rationality, German sages, savants and the Orient development of German writing (Tehreek-e-Mashraqia) were of the particular enthusiasm for him. These subjects stayed unmistakable for him for the duration of his life. He had an indwelling connection with Germany as opposed to other European nations. In such manner a few focuses are of uncommon thought A concise record of Allama Dr. Muhammad Iqbal's relations with Germany To reason out his approach towards Germany. Key Words: Persia, Germany, Philosophy, Literature, Movement of Orientalism, Future of Humanity. Allama Dr. Muhammad Iqbal’s Education and Germany Allama Dr. -

Iqbal's Response to Modern Western Thought: a Critical Analysis

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences p-ISSN: 1694-2620 e-ISSN: 1694-2639 Vol. 8 No. 5, pp. 27-36, ©IJHSS Iqbal’s Response to Modern Western Thought: A Critical Analysis Dr. Mohammad Nayamat Ullah Associate Professor Department of Arabic University of Chittagong, Bangladesh Abdullah Al Masud PhD Researcher Dept. of Usuluddin and Comparative Religion International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) ABSTRACT Muhammad Iqbal (1873-1938) is a prominent philosopher and great thinker in Indian Sub- continent as well as a dominant figure in the literary history of the East. His thought and literature are not simply for his countrymen or for the Muslim Ummah alone but for the whole of humanity. He explores his distinctive thoughts on several issues related to Western concepts and ideologies. Iqbal had made precious contribution to the reconstruction of political thoughts. The main purpose of the study is to present Iqbal‟s distinctive thoughts and to evaluate the merits and demerits of modern political thoughts. The analytical, descriptive and criticism methods have been applied in conducting the research through comprehensive study of his writings both in the form of prose and poetry in various books, articles, and conferences. It is expected that the study would identify distinctive political thought by Iqbal. It also demonstrates differences between modern thoughts and Iqbalic thoughts of politics. Keywords: Iqbal, western thoughts, democracy, nationalism, secularism 1. INTRODUCTION Iqbal was not only a great poet-philosopher of the East but was also among the profound, renowned scholars and a brilliant political thinker in the twentieth century of the world. -

A Poet of Eternal Relevance Dr

International Journal of Advanced in Management, Technology and Engineering Sciences ISSN NO : 2249-7455 A poet of Eternal Relevance Dr. Sir Mohammad Iqbal Dr. Gazala Firdoss, Lecturer Government Degree College Magam, Budgam. Abstract: This paper is a modest attempt to reflect on the essential message of Iqbal, the poet of humanity and what relevance it has for our contemporary times. We are living at a time in which mankind has made vast strides and progress in almost all fields of life. But with all these advancement in knowledge, science and technology and the information revolution, it is a tragedy to see that this is also the age of crisis, wars and bloodshed, armed aggression, social and economic injustice, human rights violation, alcoholism and drug addiction, sexual crimes and psychological disorders, increasing suicides and the disintegration of the family. All these are symptoms of a sick and decadent society, which is drifting aimlessly like a ship in an uncharted ocean. Modern man has alienated from himself and had lost the meaning and purpose of life. Really speaking, the political problems, the conflict between nations, violence and crime, environmental crisis are external manifestations of the inner crisis of the contemporary societies, manifested in social and economic injustice and the violation of human rights, denial and deprivation of the fundamental freedom of man, social disparity and inequality and in turn are causing social tensions and conflicts in human societies all over the globe. It is in this context, that Iqbal’s concept of dignity of man and the sanctity of human personality and freedom assumes significance. -

Iqbal, Muhammad (1877–1938)

Iqbal, Muhammad (1877–1938) Riffat Hassan Muhammad Iqbal was an outstanding poet-philosopher, perhaps the most influential Muslim thinker of the twentieth century. His philosophy, though eclectic and showing the influence of Muslims thinkers such as al-Ghazali and Rumi as well as Western thinkers such as Nietzsche and Bergson, was rooted fundamentally in the Qur’an, which Iqbal read with the sensitivity of a poet and the insight of a mystic. Iqbal’s philosophy is known as the philosophy ofkhudi or Selfhood. Rejecting the idea of a ‘Fall’ from Eden or original sin, Iqbal regards the advent of human beings on earth as a glorious event, since Adam was designated by God to be God’s vicegerent on earth. Human beings are not mere accidents in the process of evolution. The cosmos exists in order to make possible the emergence and perfection of the Self. The purpose of life is the development of the Self, which occurs as human beings gain greater knowledge of what lies within them as well as of the external world. Iqbal’s philosophy is essentially a philosophy of action, and it is concerned primarily with motivating human beings to strive to actualize their God-given potential to the fullest degree. Life Muhammad Iqbal was born at Sialkot in India in 1877. His ancestors were Kashmiri Brahmans; his forefathers had a predilection for mysticism, and both his father, Nur Muhammad, and his mother, Imam Bibi, had a reputation for piety. An outstanding student, Iqbal won many distinctions throughout his academic career. He passed the intermediate examination from the Scotch Mission School in Sialkot in 1893 and then moved to the Government College in Lahore, where he graduated in 1897. -

Main Philosophical Idea in the Writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938)

Durham E-Theses The main philosophical idea in the writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938) Hassan, Riat How to cite: Hassan, Riat (1968) The main philosophical idea in the writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938), Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7986/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk im MIN PHILOSOPHICAL IDEAS IN THE fffilTINGS OF m^MlfAD •IQBAL (1877- 1938) VOLUME 2 BY EIFFAT I^SeAW Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Durham for the Degree oi Doctor of Philosophy. ^lARCH 1968 Sohool of Oriental Studies, Blvet Hill, DURHAM. 322 CHAPTER VI THE DEVELOPMENT OF 'KHUDT' AMD IQBlL'S *MAED-E-MOMIN'. THE MEAMNQ OP *mJDT' Exp3.aining the meaning of the concept *KhudT', in his Introduction to the first edition of Asrar~e~ Kl^udT. -

Iqbal Review

IQBAL REVIEW Journal of the Iqbal Academy Pakistan Volume: 52 April/Oct. 2011 Number:2, 4 Pattern: Irfan Siddiqui, Advisor to Prime Minister For National History & Literary Heritage Editor: Muhammad Sohail Mufti Associate Editor: Dr. Tahir Hameed Tanoli Editorial Board Advisory Board Dr. Abdul Khaliq, Dr. Naeem Munib Iqbal, Barrister Zaffarullah, Ahmad, Dr. Shahzad Qaiser, Dr. Dr. Abdul Ghaffar Soomro, Prof. Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Dr. Fateh Muhammad Malik, Dr. Khalid Masood, Dr. Axel Monte Moin Nizami, Dr. Abdul Rauf (Germany), Dr. James W. James Rafiqui, Dr. John Walbrigde (USA), Morris (USA), Dr. Marianta Dr. Oliver Leaman (USA), Dr. Stepenatias (Russia), Dr. Natalia Alparslan Acikgenc (Turkey), Dr. Prigarina (Russia), Dr. Sheila Mark Webb (USA), Dr. Sulayman McDonough (Montreal), Dr. S. Nyang, (USA), Dr. Devin William C. Chittick (USA), Dr. Stewart (USA), Prof. Hafeez M. Baqai Makan (Iran), Alian Malik (USA), Sameer Abdul Desoulieres (France), Prof. Hameed (Egypt) , Dr. Carolyn Ahmad al-Bayrak (Turkey), Prof. Mason (New Zealand) Barbara Metcalf (USA) IQBAL ACADEMY PAKISTAN The opinions expressed in the Review are those of the individual contributors and are not the official views of the Academy IQBAL REVIEW Journal of the Iqbal Academy Pakistan This peer reviewed Journal is devoted to research studies on the life, poetry and thought of Iqbal and on those branches of learning in which he was interested: Islamic Studies, Philosophy, History, Sociology, Comparative Religion, Literature, Art and Archaeology. Manuscripts for publication in the journal should be submitted in duplicate, typed in double-space, and on one side of the paper with wide margins on all sides preferably along with its CD or sent by E-mail. -

Saminaiqbalgoetheamended.Pdf

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 10 : 9 September 2010 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. K. Karunakaran, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. Bridge between East and West - Iqbal and Goethe Samina Khan, M.Phil. Iqbal Courtesy: http://www.allamaiqbal.com/ Abstract This article aims to present a comparative analysis of the poems of Iqbal and Goethe and the influence of the latter on the former. The introductory section gives a biographical sketch of the Language in India www.languageinindia.com 255 10 : 9 September 2010 Samina Khan, M.Phil. Bridge between East and West - Iqbal and Goethe two poets and their literary accomplishments. Echo and tactical use of Goethe in Iqbal‟s texts are discussed with special reference to his Paym-e Mashriq (Message From the East, 1923) and Goethe‟s West-Ostlicher Divan (Divan of the East and West, 1819). Allama Muhammad Iqbal Iqbal was born in Sialkot in 1877 where he received his early education. For higher education he went to Lahore (1895), and did M.A. in philosophy from Government College in 1899, he had already obtained a degree in law (1898). Lahore was a center of academic and literary activity where Iqbal established himself as a poet. In 1905 he went to Cambridge which was reputed for the study of European, Arabic and Persian philosophy. -

Allama Muhammad Iqbal - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Allama Muhammad Iqbal - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Allama Muhammad Iqbal(9 November 1877 - 21 April 1938) Sir Muhammad Iqbal, also known as Allama Iqbal, was a philosopher, poet and politician in British India who is widely regarded to have inspired the Pakistan Movement. He is considered one of the most important figures in Urdu literature, with literary work in both the Urdu and Persian languages. Iqbal is admired as a prominent classical poet by Pakistani, Indian and other international scholars of literature. Although most well known as a poet, he has also been acclaimed as a modern Muslim philosopher. His first poetry book, Asrar-e-Khudi, appeared in the Persian language in 1915, and other books of poetry include Rumuz-i-Bekhudi, Payam-i-Mashriq and Zabur-i-Ajam. Some of his most well known Urdu works are Bang-i-Dara, Bal-i-Jibril and Zarb-i Kalim. Along with his Urdu and Persian poetry, his various Urdu and English lectures and letters have been very influential in cultural, social, religious and political disputes over the years. In 1922, he was knighted by King George V, giving him the title "Sir". During his years of studying law and philosophy in England, Iqbal became a member of the London branch of the All India Muslim League. Later, in one of his most famous speeches, Iqbal pushed for the creation of a Muslim state in Northwest India. This took place in his presidential speech in the league's December 1930 was very close to Quid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah. -

Main Philosophical Idea in the Writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938)

Durham E-Theses The main philosophical idea in the writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938) Hassan, Riat How to cite: Hassan, Riat (1968) The main philosophical idea in the writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938), Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7986/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE 11 PHILOSOPHICAL IDEAS IN THE WRITINGS OF MUHAMMAD IQBAL (1877 - 1938) VOLUME 1 BY RIFFAT HASSAN Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Durham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. MARCH 1968 School of Oriental Studies Elvet Hills Durham* The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. mmvf I* Chapter One eoateiiie the M^gFa^Mcsal stalls of Xqbll1® Hf lie Ch^ttr Y^o Is coneiraeO.