Critical Readings in Bodybuilding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL 2021 Regular Session SENATE

SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL 2021 Regular Session SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 63 BY SENATOR BERNARD COMMENDATIONS. Commends Ronnie Coleman on being inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. 1 A RESOLUTION 2 To commend Ronnie Coleman on being inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. 3 WHEREAS, Ronnie Dean Coleman was born in Monroe, Louisiana, on May 13, 4 1964, and was a native of Bastrop, Louisiana; and 5 WHEREAS, he reached a high-level playing football during high school which 6 motivated him to lift weights and set out on his fitness journey; and 7 WHEREAS, Ronnie's performance as a football player led to a scholarship offer to 8 Grambling State University to study accounting and play football; and 9 WHEREAS, he played football as a middle linebacker with the GSU Tigers under 10 coach Eddie Robinson; and 11 WHEREAS, Ronnie Coleman graduated cum laude from Grambling State University 12 in 1984 with a bachelor's degree in accounting; and 13 WHEREAS, upon graduation he moved to Texas in search of work and eventually 14 became a police officer in Arlington, Texas, where he was an officer from 1989 to 2000 and 15 a reserve officer until 2003; and 16 WHEREAS, Ronnie joined the world famous Metroflex Gym, where he quickly 17 developed a bond with the owner, Brian Dobson; and 18 WHEREAS, Mr. Dobson ultimately gave Ronnie a lifetime free membership if he Page 1 of 3 SLS 21RS-918 ORIGINAL SR NO. 63 1 allowed Mr. Dobson to train him for competition; and 2 WHEREAS, Ronnie's hard work and determination lead to him winning the 1990 Mr. -

'Freaky:' an Exploration of the Development of Dominant

From ‘Classical’ To ‘Freaky:’ an Exploration of the Development of Dominant, Organised, Male Bodybuilding Culture Dimitrios Liokaftos Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London Submitted for the Degree of PhD in Sociology February 2012 1 Declaration: The work presented in this thesis is my own. Dimitrios Liokaftos Signed, 2 Abstract Through a combination of historical and empirical research, the present thesis explores the development of dominant, organized bodybuilding culture across three periods: early (1880s-1930s), middle (1940s-1970s), and late (1980s-present). This periodization reflects the different paradigms in bodybuilding that the research identifies and examines at the level of body aesthetic, model of embodied practice, aesthetic of representation, formal spectacle, and prevalent meanings regarding the 'nature' of bodybuilding. Employing organized bodybuilding displays as the axis for the discussion, the project traces the gradual shift from an early bodybuilding model, represented in the ideal of the 'classical,' 'perfect' body, to a late-modern model celebrating the 'freaky,' 'monstrous' body. This development is shown to have entailed changes in notions of the 'good' body, moving from a 'restorative' model of 'all-around' development, health, and moderation whose horizon was a return to an unsurpassable standard of 'normality,' to a technologically-enhanced, performance- driven one where 'perfection' assumes the form of an open-ended project towards the 'impossible.' Central in this process is a shift in male identities, as the appearance of the body turns not only into a legitimate priority for bodybuilding practitioners but also into an instance of sport performance in bodybuilding competition. Equally central, and related to the above, is a shift from a model of amateur competition and non-instrumental practice to one of professional competition and extreme measures in search of the winning edge. -

Download High-Intensity Training the Mike Mentzer Way, Mike

High-Intensity Training the Mike Mentzer Way, Mike Mentzer, John R. Little, McGraw-Hill, 2002, 0071383301, 9780071383301, 288 pages. A PAPERBACK ORIGINALHigh-intensity bodybuilding advice from the first man to win a perfect score in the Mr. Universe competitionThis one-of-a-kind book profiles the high-intensity training (HIT) techniques pioneered by the late Mike Mentzer, the legendary bodybuilder, leading trainer, and renowned bodybuilding consultant. His highly effective, proven approach enables bodybuilders to get results--and win competitions--by doing shorter, less frequent workouts each week. Extremely time-efficient, HIT sessions require roughly 40 minutes per week of training--as compared with the lengthy workout sessions many bodybuilders would expect to put in daily.In addition to sharing Mentzer's workout and training techniques, featured here is fascinating biographical information and striking photos of the world-class bodybuilder--taken by noted professional bodybuilding photographers--that will inspire and instruct serious bodybuilders and weight lifters everywhere.. DOWNLOAD HERE http://bit.ly/1f8Qgh8 The World Gym Musclebuilding System , Joe Gold, Robert Kennedy, 1987, Health & Fitness, 179 pages. Briefly describes the background of World's Gym, tells how to get started in bodybuilding, and discusses diet, workout routines, and competitions. The Gold's Gym Training Encyclopedia , Peter Grymkowski, Edward Connors, Tim Kimber, Bill Reynolds, Sep 1, 1984, Health & Fitness, 272 pages. Demonstrates exercises and weight training routines for developing one's biceps, chest, shoulders, back, thighs, hips, triceps, abdomen, and forearms. Solid gold training the Gold's Gym way, Bill Reynolds, 1985, Health & Fitness, 216 pages. Discusses the basics of bodybuilding and provides guidance on the use of free weights and exercise equipment to develop the body. -

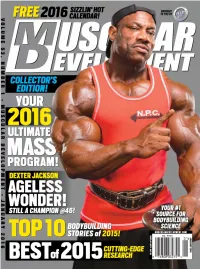

Muscular Development Is Your Number-One Source for Building Muscle, and for the Latest Research and Best Science to Enable You to Train Smart and Effectively

BONUS SIZE BONUS SIZE %MORE % MORE 20 FREE! 25 FREE! MUSCLETECH.COM MuscleTech® is America’s #1 Selling Bodybuilding Supplement Brand based on cumulative wholesale dollar sales 2001 to present. Facebook logo is owned by Facebook Inc. Read the entire label and follow directions. © 2015 NEW! PRO SERIES The latest innovation in superior performance from This complete, powerful performance line features the MuscleTech® is now available exclusively at Walmart! same clinically dosed key ingredients and premium The all-new Pro Series is a complete line of advanced quality you’ve come to trust from MuscleTech® over supplements to help you maximize your athletic the last 20 years. So you have the confi dence that potential with best-in-class products for every need: you’re getting the best research-based supplements NeuroCore®, an explosive, fast-acting pre-workout; possible – now at your neighborhood Superstore! CreaCore®, a clinically dosed creatine amplifier; MyoBuild®4X, a powerful amino BCAA recovery formula; AlphaTest®, a Clinically dosed, lab-tested key ingredients max-strength testosterone booster; and Muscle Builder, Formulated and developed based on the extremely powerful, clinically dosed musclebuilder. multiple university studies Plus, take advantage of the exclusive Bonus Size of Fully-disclosed formulas – no hidden blends our top-selling sustained-release protein – PHASE8TM. Instant mixing and amazing taste ERICA M ’S A # SELLING B Gŭŭ S OD IN UP YBUILD ND PLEMENT BRA BONUS SIZE MORE 33%FREE! EDITOR’s LETTER BY STEVE BLECHMAN, Publisher and Editor-in-Chief DEXTER JACKSON IS ‘THE BLADE’ BODYBUILDING’S NEXT GIFT? eing the number-one bodybuilder in the world is an achievement that commands respect from fans and fellow competitors alike. -

Attaining Olympus: a Critical Analysis of Performance-Enhancing Drug Law and Policy for the 21St Century

Franco Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/16/19 11:35 PM ATTAINING OLYMPUS: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF PERFORMANCE-ENHANCING DRUG LAW AND POLICY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY ALEXANDRA M. FRANCO1 ABSTRACT While high-profile doping scandals in sports always garner attention, the public discussion about the use of performance-enhancing substances ignores the growing social movement towards enhancement outside of sports. This Article discusses the flaws in the ethical origins and justifications for modern anti-doping law and policy. It analyzes the issues in the current regulatory scheme through its application to different sports, such as cycling and bodybuilding. The Article then juxtaposes those issues to general anti-drug law applicable to non-athletes seeking enhancement, such as students and professionals. The Article posits that the current regulatory scheme is harmful not only to athletes but also to people in general—specifically to their psychological well-being—because it derives from a double social morality that simultaneously shuns and encourages the use of performance-enhancing drugs. I. INTRODUCTION “Everybody is going to do what they do.” — Phil Heath, Mr. Olympia champion.2 The relationship between performance-enhancing drugs and American society has been problematic for the past several decades. High- profile doping scandals regularly garner media attention—for example, 1. © Alexandra M. Franco, J.D. The Author is an Affiliated Scholar at the Institute for Science, Law and Technology at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. She previously worked as a Judicial Law Clerk for the Honorable Franklin U. Valderrama in the Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois (the views expressed in this Article are solely those of the Author, and do not represent those of Equal Justice Works or Cook County). -

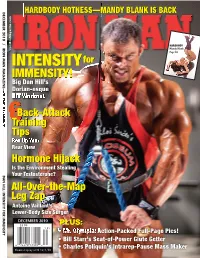

Intensityfor

DECEMBER 2010 / IRON MAN MAGAZINE— DECEMBER 2010 / IRON MAN MAGAZINE— HARDBODY HOTNESS—MANDY BLANK IS BACK TERRY, ™ Vertical Web ad- dress is obscured by logo. HARDBODY Mandy Blank IronManMagazine.com Page 182 INTENSITY for IMMENSITY! Big Dan Hill’s WE KNOW TRAINING Dorian-esque HIT Workout Back-Attack ™ 6Training DAN HILL: INTENSITY FOR IMMENSITY Tips Rev Up Your Rear View Hormone Hijack Is the Environment Stealing Your Testosterone? All-Over-the-Map Leg Zap Antoine Vaillant’s Lower-Body Size Surger DECEMBER 2010 $5.99 PLUS: • Mr. Olympia: Action-Packed Full-Page Pics! • Bill Starr’s Seat-of-Power Glute Getter • Charles Poliquin’s Intrarep-Pause Mass Maker Please display until 12/1/10 FC_DEC_2010_F.indd 1 10/5/10 12:14:35 PM CONTEWE KNOW TRAINING™ NTS DECEMBER 2010 80 FEATURES DAN HILL 56 TRAIN, EAT, GROW 134 Hit the growth threshold with 4X training, and you’ll build new mass—guaranteed. 80 INTENSITY FOR IMMENSITY New pro Dan Hill, 24, works at getting huge—in and out of the gym. 98 HORMONE HIJACK Is the environment stealing your muscle gains? It’s very possible, and Jerry Brainum has some solutions. 116 A BODYBUILDER IS BORN: GENERATIONS Ron Harris hammers home some old-school iron wisdom: Treat all your children the same. 120 CANADIAN WHEELS Cory Crow gets the lowdown on Antoine Vaillant’s all-over-the-map leg zap. 120 CANADIAN WHEELS Contents_F.indd 18 10/4/10 5:49:56 PM DECEMBER 2010 / IRON MAN MAGAZINE— HARDBODY HOTNESS—MANDY BLANK IS BACK Dan Hill appears ™ Vertical Web ad- on this month’sdress is obscured HARDBODY Mandy Blank IronManMagazine.com cover. -

GMV Productions

GMV Productions Over 50 years of mail order and world-wide internet trading. WHAT SORT OF SERVICE CAN I EXPECT? You will receive the fastest, most friendly and courteous service, the equal of the very best web based mail order trader. As a general rule, all orders go the same day they are received. If you have a problem, email me personally at [email protected]<a target="_blank"></a> OUR GMV PRINCIPLES OF DOING BUSINESS The Guiding Principle. We believe in doing what's right for our customers. We will do whatever is necessary to satisfy your requests and fill your orders promptly. GMV Productions www.gmv.com.au has the largest collection of bodybuilding DVDs in the world featuring the top male and female bodybuilders and fitness athletes. GMV Bodybuilding www.gmvbodybuilding.com has one of the largest selections of male and female Digital Downloads of bodybuilders, contests and fitness athletes. All of our downloadable videos have been transferred directly from the original video master tapes and we are using the latest compression technology to produce high quality MP4 videos. We can say this because GMV Productions has been filming bodybuilding features, posing routines, events such as Olympias, Mr. Universe contests to natural amateur competitions, strongman, pump rooms, strength events, powerlifting and fitness expos - since 1965. In addition to the biggest range of titles, we also have the biggest names. These include, but are not restricted to names such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Ronnie Coleman, Dorian Yates, Lee Haney, Jay Cutler, Sergio Oliva and all of the Olympia winners to present-day stars such as Phil Heath, Kai Greene, Dennis Wolf, Shawn Rhoden, Flex Lewis, Branch Warren etc amongst the men and every Ms Olympia winner, Iris Kyle, Cory Everson, Yaxeni Oriquen, Adela Garcia, Nicole Wilkins, Oksana Grishina, Alina Popa etc amongst the women. -

Arthur Jones: an Unconventional Character

March 2005 Iron Game History Arthur Jones: AN UNCONVENTIONAL CHARACTER Bill Pearl It's impossible to overlook this opportunity to give you more insight on the Arthur Jones I know. He is, by far, one of the most unique individuals I've ever met. Mike Mentzer (former I.F.B.B. Mr. America winner) attempted to describe Arthur by stating, "Arthur Jones is not a relaxing person to be with. He does not lightly Although Arthur Jones loved his coffee and cigarettes, he loved resistance training, too, and he practiced it in his exchange words. He spews facts, torrents of them, earlier years. In the early 1960s, as this photo attests, gleaned from studies and perhaps more important, from Jones possessed an admirable physique. practical application of theory, personal observations er 'gawd'-damn wildlife that I capture in South America. and incisive deduction. You don't converse with Arthur But I'm not new to the film business. I've made several Jones: you attend his lectures. He is opinionated, chal- documentaries." "When do you plan to start filming?" I lenging, intense and blunt." asked. "As soon as I can get your ass down to I am in total agreement with Mike. This is just a Louisiana." "What am I supposed to do in this movie?" taste of my on-again/off-again relationship with Arthur, "Whatever it takes to make the 'gawd'-damn thing sell!" which began in 1958. Early one Monday morning, while "How much are you willing to pay?" "How much are I was opening the door to my Sacramento gym, Arthur you worth?" We agreed on a price and, to this day, I've appeared out of nowhere. -

Sample Workouts for Each Muscle Group Chest Muscles Back Muscles Leg Muscles

Intensity Responsive Lifters Mark Sherwood For more information from the author visit: http://www.precisionpointtraining.com/ Copyright © 2019 by Mark Sherwood Intensity Responsive Lifters By Mark Sherwood The author and publisher of the information in this book are not responsible in any manner for physical harm or damages that may occur in response to following the instructions presented in this material. As with any exercise program, a doctor’s approval should be obtained before engaging in exercise. Table Of Contents Introduction Chapter 1: Always Train To Failure Chapter 2: Forced Reps Chapter 3: Rest Pause Reps And Rest Pause Clusters Chapter 4: Partial Rep Burns Chapter 5: Negatives Chapter 6: Pre-Exhaust Chapter 7: Drop Sets or Strip Sets Chapter 8: Exercises Chapter 9: How Much Training And How Often? Chapter 10: Change Your Workouts Chapter 11: Rep Speed Chapter 12: Warm up Sets Chapter 13: Sample High Intensity Workouts Chapter 14: Workout Schedules Chapter 15: The High Intensity Option About The Author Additional Resources Introduction In the 1970’s, a talented young bodybuilder by the name of Mike Mentzer was doing his best to ascend the ranks of competitive bodybuilding. His journey started out with a very basic training program as an early adolescent. By the time he was 15, he had already developed an outstanding body. Having a taste of bodybuilding success, he began to add on to his basic three sets per muscle group workouts. He reasoned that he needed to do this because all of the top bodybuilders that he knew about were doing high volume workouts. -

Mike Mentzer - Bodybuilder, Writer, and Philosopher by Bob Burns

Mike Mentzer - Bodybuilder, Writer, and Philosopher by Bob Burns Mike Mentzer was born on November 15, 1951 in Germantown, PA and grew up in Ephrata, PA. Mike did well in grammar school as well as high school, "sometimes getting all A's, though mostly A's and B's." His father nurtured Mike's academic motivation and performance by providing him with various kinds of inducements, from a baseball glove to hard cash. Years later, Mike said that his father "unwittingly … was inculcating in me an appreciation of capitalism." Mike's 12th grade teacher, Elizabeth Schaub, apparently left her mark on Mike -- he credits her for his love "of language, thought, and writing." Ms. Schaub was one of those "'old-fashioned' no nonsense type" of teachers who expected her students to master whatever she taught in class.1 Mike started bodybuilding when he was 12 years of age at a bodyweight of 95 pounds after seeing the men on the covers of several muscle magazines. Mike's father had bought him set of weights and an instruction booklet. The booklet suggested that he train no more than 3 days a week so Mike did just that. This training regime worked for Mike quite well in fact. By age 15, his bodyweight had reached 165 pounds at which point Mike could bench press 370 pounds! Mike's goal at the time was to look like his hero, Bill Pearl, a famous bodybuilder of the 1950s and 1960s. In Mike's book, Heavy Duty: A Logical Approach to Muscle Building, published circa 1980, he wrote: Now that my resolve to be a top bodybuilder had moved up a notch, it was time to start training like other top bodybuilders, I thought. -

Check out Casey's New Flex Article

BY CHRIS LUND, UK EDITOR SINCE 1985 PHOTOS BY CHRIS LUND RETROSPECTIVE with Casey during one of these secret workouts. So just how was he training? How did he build those incredible arms that looked as though they were bigger than his head? The best training article that appeared on Casey during this period was written by Achilles Kallos and published in the October 1971 edition of Iron Man. This article listed Casey´s measurements as Height 5 ft 8 ins; body weight 217 pounds; arms 193/8 ins (cold); chest 50 ins; waist 31½ ins; thighs 28 ins; and calves 18 ins. The article also mentioned the fact that Casey trained his whole body in one workout, three times per week, and that each workout lasted between two and two-and-a- half hours. The writer then detailed the amazing workout that he claimed Casey followed during that period. LEGS L eg Press: One set of 20 reps with 750 pounds Leg Extension:. One set of 14-20 reps with 250 pounds S quat: One set of 14-20 reps with 505 pounds L eg Curl: One set of 14-20 reps with 150 pounds The most amazing thing about this leg CASEY VIATOR workout was the fact that Casey did each exercise nonstop, going from one exercise to The fi rst detailed article and photos on CASEY VIATOR another without rest! appeared in the September 1970 issue of Iron Man magazine, BACK just after his Junior Mr America win, and clean sweep of every N autilus Pullover Machine: Three sets of single body part with the exception of abdominals! 20 reps C ircular Pulldown: Three sets of 20 reps. -

By Brian D. Johnston Care Has Been Taken to Confirm The

By Brian D. Johnston Copyright ©2005 by BODYworx TM All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form Published by BODYworx Publishing 5 Abigail Court Sudbury, ON Canada ISBN 0-9732409-9-7 Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of information presented in this manual. The author, editors, and the publisher, however, cannot accept any responsibility for errors or omissions in this manual, and make no warranty, express or implied, with respect to its contents. The information in this manual is intended only for healthy men and women. People with health problems should not follow the suggestions without a physician's approval. Before beginning any exercise or dietary program, always consult with your doctor. Table of Contents Preface i CHAPTER 1: History and Philosophy of High Intensity Training 1 High Intensity Strength Training – A Brief History 2 Gems From History 3 The King has Arrived – Arthur Jones 6 The Off-spring of HIT 11 Negative Perspectives of High Intensity Training 12 High Intensity versus High Volume 15 Physiological Effects of HIT and HVT 18 Erroneous Perceptions About HIT 20 Why High Volume Training? 29 CHAPTER 2: Fundamentals of High Intensity Training 33 Overview 33 Basic Principles of Exercise 35 General Exercise Rules 39 Stress Physiology and The General Adaptation Syndrome 39 Relating GAS to Exercise 41 Local Adaptation Syndrome 41 General Adaptation Syndrome 41 Exercise and GAS (charts) 43 Hormonal Secretions 45 Exercise Stress Guidelines 48 Exercise Principle Relationships