AK Aviators Safety Handbook 2017 Ver3.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alaska Range

Alaska Range Introduction The heavily glacierized Alaska Range consists of a number of adjacent and discrete mountain ranges that extend in an arc more than 750 km long (figs. 1, 381). From east to west, named ranges include the Nutzotin, Mentas- ta, Amphitheater, Clearwater, Tokosha, Kichatna, Teocalli, Tordrillo, Terra Cotta, and Revelation Mountains. This arcuate mountain massif spans the area from the White River, just east of the Canadian Border, to Merrill Pass on the western side of Cook Inlet southwest of Anchorage. Many of the indi- Figure 381.—Index map of vidual ranges support glaciers. The total glacier area of the Alaska Range is the Alaska Range showing 2 approximately 13,900 km (Post and Meier, 1980, p. 45). Its several thousand the glacierized areas. Index glaciers range in size from tiny unnamed cirque glaciers with areas of less map modified from Field than 1 km2 to very large valley glaciers with lengths up to 76 km (Denton (1975a). Figure 382.—Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the Alaska Range in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image mosaic from Mike Fleming, Alaska Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, Alaska. The numbers 1–5 indicate the seg- ments of the Alaska Range discussed in the text. K406 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD and Field, 1975a, p. 575) and areas of greater than 500 km2. Alaska Range glaciers extend in elevation from above 6,000 m, near the summit of Mount McKinley, to slightly more than 100 m above sea level at Capps and Triumvi- rate Glaciers in the southwestern part of the range. -

Standard 62.2-2010 Addendum N

ANSI/ASHRAE Addendum n to ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.2-2010 Ventilation and Acceptable Indoor Air Quality in Low-Rise Residential Buildings Approved by the ASHRAE Standards Committee on January 21, 2012; by the ASHRAE Board of Directors on January 25, 2012; and by the American National Standards Institute on January 26, 2012. This addendum was approved by a Standing Standard Project Committee (SSPC) for which the Standards Committee has estab- lished a documented program for regular publication of addenda or revisions, including procedures for timely, documented, con- sensus action on requests for change to any part of the standard. The change submittal form, instructions, and deadlines may be obtained in electronic form from the ASHRAE Web site (www.ashrae.org) or in paper form from the Manager of Standards. The latest edition of an ASHRAE Standard may be purchased on the ASHRAE Web site (www.ashrae.org) or from ASHRAE Customer Service, 1791 Tullie Circle, NE, Atlanta, GA 30329-2305. E-mail: [email protected]. Fax: 404-321-5478. Telephone: 404-636-8400 (worldwide), or toll free 1-800-527-4723 (for orders in US and Canada). For reprint permission, go to www.ashrae.org/permissions. © 2012 ASHRAE ISSN 1041-2336 © ASHRAE (www.ashrae.org). For personal use only. Additional reproduction, distribution, or transmission in either print or digital form is not permitted without ASHRAE's prior written permission. ASHRAE Standing Standard Project Committee 62.2 Cognizant TC: TC 4.3, Ventilation Requirements and Infiltration SPLS Liaison: Robert G. Baker Steven J. Emmerich, Chair* Thomas P. Heidel Armin Rudd Don T. -

Alaska Region (AAL) Runway Safety Plan, FY 2020

COMMITTED TO CONTINUOUSLY IMPROVING SURFACE SAFETY. Alaska Region (AAL) Runway Safety Plan FY20 2019-2020 RUNWAY SAFETY COUNCIL (RSC) #45 www.faa.gov Executive Summary The Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) top data, development of new safety metrics, and priority is maintaining safety in the National leveraged organizational capabilities in support TABLE Airspace System (NAS). The goal for runway of meeting this goal. safety is to improve safety by decreasing the OF CONTENTS FAA Safety Management System (SMS) 4 number and severity of Runway Incursions (RI), In support of the NRSP, and in support of Runway Excursions (RE) and serious Surface Air Traffic Organization (ATO) Safety and Incidents. FAA’s 2018- 2020 National Runway Technical Training (AJI) FY2018 Business Plan, the Alaskan Region (AAL) has developed this Regional Runway Safety Plan (RRSP) Methodology Safety Plan (NRSP) outlines the FAA’s strategy 6 to adapt its runway safety efforts through Regional Runway Safety Plan (RRSP) to provide enhanced collection and integrated analysis of a roadmap with regional emphasis for FY2020. 7 FY20 RRSP Initiatives 8 Safety Assurance 10 Safety Risk Management (SRM) 12 Safety Policy 16 Safety Promotion 4 Alaskan Region (AAL) Runway Safety Plan FY20 Alaskan Region (AAL) Runway Safety Plan FY20 5 FAA Safety Management FY18-FY20 NRSP Objectives System (SMS) SAFETY FAA is employing and evolving a Safety The National Runway Safety Plan 2018-2020 ASSURANCE Identify Operating Hazards Management System (SMS), which provides a aligns our strategic priorities with established Program Data formalized and proactive approach to system Safety Risk Management principles. The plan Remain the global leader in assuring Voluntary Safety Reporting safety in order to find, analyze and address defines how the FAA, airports, and industry runway safety enhancement initiatives Investigations risk in the NAS. -

Alaskan Region AAL-5 701 C St

January 26, 1981 81-3 Public Affairs Office FAA -Alaskan Region AAL-5 701 C St . , Box 14 Anchorage, AK 99513 (907) 271 - 5296 Alaskan US Deportrnenl of Tronsporlahon Federal Avlollon Intercom Administration NATIONAL HONORS 2 COVER STORY Though we're a bit late in publishing Pacific Contractors and NANA have moved tnese photos, we just got them--and we in more double-wide trailers for two have a new opportunity to pay additional camps to house 120 more men each. crazy tribute to the accomplishments of Horse Camp at Deadhorse has reopended and Joan M. Gillis and Frank Babiak, shown will house 150 men. ARCO and SOHIO each receiving Departmental national honors at plan to build new 500 man camps in the the 13th Annual DOT Awards Ceremony in area. Washington. Making the presentations was former Secretary of Transpor tation Increased activity has already been borne Neil Goldschmidt. The awards were for out by Fairbanks relief specialists outstanding performance in the region. already being put on standby by Wien for Babiak, Manager of the Anchorage Airway January flights, even though reservations Facilities Sector, was honored for are made a month in advance. Additional exceptional effort in the EEO field. flights are planned by Wien. Gillis, Administrative Assistant at the Anchorage _ Sector was given a special The Fairbanks FSS is care fully watching commendation for helping to set the this buildup in order to anticipate a office in order following its almost need for increased watch coverage due to total destruction in a fire in January traffic increases. o f 1979. -

Breasts on the West Buttress Climbing the Great One for a Great Cause

Breasts on the West Buttress Climbing the Great One for a great cause Nancy Calhoun, Sheldon Kerr, Libby Bushell A Ritt Kellogg Memorial Fund Proposal Calhoun, Kerr, Bushell; BOTWB 24 Table of Contents Mission Statement and Goals 3 Libby’s Application, med. form, agreement 4-8 Libby’s Resume 9-10 Nancy’s Application, med. form, agreement 11-15 Nancy’s Resume 16-17 Sheldon’s Application, med. form, agreement 18-23 Sheldon’s Resume 24-25 Ritt Kellogg Fund Agreement 26 WFR Card copies 27 Travel Itinerary 28 Climbing Itinerary 29-34 Risk Management 35-36 Minimum Impact techniques 37 Gear List 38-40 First Aid Contents 41 Food List 42-43 Maps 44 Final Budget 45 Appendix 46-47 Calhoun, Kerr, Bushell; BOTWB 24 Breasts on the West Buttress: Mission Statement It may have started with the simple desire to climb North America’s tallest peak, but with a craving to save the world a more pressing concern on the minds of three Colorado College women (a Vermonter, an NC southern gal, and a life-long Alaskan), we realized that climbing Denali could and should be only a mere stepping stone to the much greater task at hand. Thus, we’ve teamed up with the American Breast Cancer Foundation, an organization that is doing their part to save our world, one breast at a time, in order to do our part, in hopes of becoming role models and encouraging the rest of the world to do their part too. So here’s our plan: We are going to climb Denali (Mount McKinley) via the West Buttress route in June of 2006. -

2018 Annual Mountaineering Summary

2018 Annual Mountaineering Summary NPS Photo (M. Coady) 2018 Statistical Year in Review Each season's !!!~~D.~~.iD.~.~- ~!~~ . !:.~':!.!~ . ~!~!!~!!~~ · including total attempts and total summits for Denali and Foraker, are now compiled into one spreadsheet spanning from 1979 to 2018. The P.~ .':1.~.1 ! ..l?.!~P.~!~~~~ blog can provide a more detailed perspective of the 2018 season, including daily statistics, weather, conditions reports, photos, and random climbing news. Thank you to the 31 !!!~~!:.'~.~.i.':1.~.~-~!~~t~.<?.1.':l. ~!~~~~ ~! .':1::~~~~! (VIP's) who teamed up with Denali rangers to staff the mountain camps in 2018. Read about the efforts of the 2018 recipients of the M.i.:;. 1.~~:~~~- ~~~~ - g-~D.~.l.i.. ~~~ Award. Quick Facts - Denali • Climbers from the USA: 694 (63% of total) Climbers hailed from 42 of the 50 states in 2018. Colorado was the most heavily represented with 114 climbers. Alaska followed close behind with 111 climbers. There were 87 climbers from Washington and 72 from California. • International climbers: 420 (37% of total) 51 foreign nations were represented on Denali in 2018. Of the international climbers, Poland generated the highest number of climbers with 47. Canada was next with 42. Australia was suprisingly well-represented on Denali this season, with 28 climbers. China and Japan each had 24 climbers on Denali. We had one climber each from Andorra, Kazakhstan, and Qatar. • Average trip length The average trip length on Denali was 17 days; independent teams averaged a day less (16 days), while guided teams averaged a day more (18 days). The average length of a Muldrow Glacier climb was 27 days. -

Radio Control Tower, Southwest Buttress, It's Included

AAC Publications Radio Control Tower, southwest buttress, It’s Included Alaska, Central Alaska Range In June, Alan Rousseau and I flew into the Southeast Fork of the Kahiltna Glacier between guiding trips on Denali to see what we could get done. With huge amounts of snowfall and warming temps, we ruled out all routes with snow above them. We decided to get a bit creative. This led us up a new route on the very rocky southwest buttress of Radio Control Tower (8,670’), which is located just east of Kahiltna Base Camp. The route was an interesting outing with some harder pitches and lots of exploration required to reach the top of the buttress: It’s Included (1,000’, 5.10+ AI3 M7). – Mark Pugliese Editor’s note: Previously unreported, in May 2013, Alan Rousseau and Aaron Kurland made the first recorded ascent of the west face of Radio Control Tower, climbing a prominent gully and snow-ramp system just left of the southwest buttress. They called the seven-pitch climb Spindrift Couloir (1,000’, AI3 M5). Given the proximity of Radio Control Tower to the Kahiltna Base Camp it’s possible other routes have gone unreported. Images The southwest buttress of Radio Control Tower showing the new route It’s Included (1,000’, 5.10+ AI3 M7). The west face of Radio Control Tower showing the previously unreported route Spindrift Couloir (1,000’, AI3 M5). The new route It’s Included climbs the buttress just to the right. Article Details Author Mark Pugliese Publication AAJ Volume 57 Issue 89 Page 0 Copyright Date 2015 Article Type Climbs and expeditions. -

Building Energy Asset Score Program Overview and Technical Protocol

PNNL-22045 Rev. 1.2 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Building Energy Asset Score Program Overview and Technical Protocol (Version 1.2) N Wang S Goel V Srivastava A Makhmalbaf September 2015 PNNL-22045 Rev. 1.2 Building Energy Asset Score Program Overview and Technical Protocol (Version 1.2) N Wang S Goel V Srivastava A Makhmalbaf September 2015 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Richland, Washington 99352 Summary The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is developing a voluntary national scoring system for commercial and multi-family residential buildings to help building owners and managers assess a building’s energy-related systems independent of operations. The goal of the score is to encourage cost- effective investment in energy efficiency improvements for these types of buildings. The system, known as the Building Energy Asset Score, will allow building owners and managers to compare their building infrastructure against peers and track energy efficiency impacts of building upgrades over time. The system will also help other building stakeholders (e.g., building investors, tenants, financiers, and appraisers) understand the relative efficiency of different buildings in a way that is independent from operations and occupancy. Prior to developing the Asset Score, DOE performed a market study1 to ensure that the effort would help address market needs and fill identified gaps. In 2012, DOE began initial pilot testing of the Asset Score. In 2013, DOE continued to assess the Asset Score through additional pilot testing and a variety of technical evaluations and performance analyses. -

Air Passenger and Cargo Transportation in Alaska

PROPERTYOF ISER , FILECOPY DoNot Remove REVIEW OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS A UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA, INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL, ECONOMIC AND GOVERNMENT RESEARCH VOL. VI, NO. 2 AIRPASSENGER ANDCARGO TRANSPORTATION IN ALASKA The air transportation industry in Alaska is undergoing March that they were beginning an Alaskan Service Inves dramatic changes, which are likely to further strengthen tigation . In an announcement to the airlines and other in its economic value to the state. New technology and trans terested parties, the CAB stated; "The board has decided port needs are increasing carrier competitiveness, while to undertake a comprehensive review of major route pat rising equipment and operating costs are lowering profit terns serving Alaska. margins. These conditions, plus growing reluctance on the " It has been over ten years since the board completed part of the federal government to subsidize less efficient an extensive examination of intra-Alaska air transporta operations, have resulted in attempts to increase efficiency tion requirements and almost four years since we last ex through airline mergers . amined the need for realignment and rievision of the four In 1967, Western Airlines International, plagued by an carrier air route complex between the Pacific Northwest announced profit squeeze on its western continental U.S. and Alaska. Significant changes in recent years suggest and Mexican routes, purchased Seattle based Pacific that the time is now ripe for a broad-scale investigation Northern Airlines and expanded operations into Alaska. into Alaskan air transportation requirements. A sound air Alaska Airlines in the past two years acquired Cordova transportation system is vital to the Alaskan economy and Airlines ( the former Coastal and Ellis_Airlines), extending the board intends to examine the entire Alaskan air route its routes throughout Southeastern Alaska and into Dawson, structure to determine what changes are necessary to pro Y.T., Canada. -

Summit Lake Big Lake Butte Lake

150°0'0"W 149°0'0"W 148°0'0"W 147°0'0"W Boulder Creek ALM Threemile Creek ALM ALM BID WLMALM BID Moose Creek Chicken Creek Elsie Creek Eva Creek WLMGlacier Creek Cody Creek Steep Creek ALM Liberty Bell MineWilson Creek Saint Charles Creek McAdam Creek Grubstake Creek Little Moose Creek Lynx Creek Fourth of July Creek Rock Creek Eagle Creek Coal Creek Slide Creek Marguerite CreekBonanza Creek Moose CreekSheep Creek 64°0'0"N ALM Emma CreekWinter Creek Homestake Creek ALM Walker Creek Coal Creek 64°0'0"N Sheep Creek ALM Plarmigan Creek Last Chance Creek Newman Creek ALM Ptarmigan Lake Mystic Mountain Slate Creek Thistle Creek Platt CreekFox Creek Shovel CreekNeedle Rock East Fork Little Delta RiverWest Fork Little Delta River Needle Creek DexAtellr GCorelde Ck reek Jumbo Dome Surprise Creek Chitsia Mountain Davis Creek Chute Creek Rogers Creek Buchanan Creek Walker Dome Mystic Creek Red Mountain Creek Iowa Creek Little Panguingue Creek Panguingue Creek Portage Creek Keevy Peak Popovitch Creek Sanderson Creek Savage River Whiskey Pup Louise Creek ALM Frances Creek Fish Creek Lignite Usibelli Peak Rock Creek East Fork Toklat River ALM Lignite Creek Lathrop, Mount Copper Creek Wigand Creek Virginia CreekKansas Creek O'Brien Creek Alder Creek Poker Creek Eightmile Lake Dry Creek Little Bear Creek Gold Run Gagnon Creek Slate Creek Coal Creek Cripple Creek Canyon Creek Glory Creek Cripple Creek Mine IPS French Gulch Crooked Creek UUssibibeelllili Mine Alaska Creek Forgotten Creek HealyHealy Dora Creek SuSnutnratrnacnaa Creek Healy CreekMoody Creek -

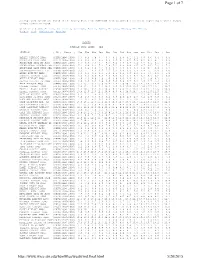

Page 1 of 7 5/20/2015

Page 1 of 7 Average wind speeds are based on the hourly data from 1996-2006 from automated stations at reporting airports (ASOS) unless otherwise noted. Click on a State: Arizona , California , Colorado , Hawaii , Idaho , Montana , Nevada , New Mexico , Oregon , Utah , Washington , Wyoming ALASKA AVERAGE WIND SPEED - MPH STATION | ID | Years | Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec | Ann AMBLER AIRPORT AWOS |PAFM|1996-2006| 6.7 8.5 7.9 7.7 6.7 5.3 4.8 5.1 6.1 6.8 6.6 6.4 | 6.5 ANAKTUVUK PASS AWOS |PAKP|1996-2006| 8.9 9.0 9.1 8.6 8.6 8.5 8.1 8.5 7.6 8.2 9.3 9.1 | 8.6 ANCHORAGE INTL AP ASOS |PANC|1996-2006| 6.7 6.0 7.5 7.7 8.7 8.2 7.8 6.8 7.1 6.6 6.1 6.1 | 7.1 ANCHORAGE-ELMENDORF AFB |PAED|1996-2006| 7.3 6.9 8.1 7.6 7.8 7.2 6.8 6.4 6.5 6.7 6.5 7.2 | 7.1 ANCHORAGE-LAKE HOOD SEA |PALH|1996-2006| 4.9 4.2 5.8 5.7 6.6 6.3 5.8 4.8 5.3 5.2 4.7 4.4 | 5.3 ANCHORAGE-MERRILL FLD |PAMR|1996-2006| 3.2 3.1 4.4 4.7 5.5 5.2 4.8 4.0 3.9 3.8 3.1 2.9 | 4.0 ANIAK AIRPORT AWOS |PANI|1996-2006| 4.9 6.6 6.5 6.4 5.6 4.5 4.2 4.0 4.6 5.5 5.5 4.1 | 5.1 ANNETTE AIRPORT ASOS |PANT|1996-2006| 9.2 8.2 8.9 7.8 7.4 7.0 6.2 6.4 7.2 8.3 8.6 9.8 | 8.0 ANVIK AIRPORT AWOS |PANV|1996-2006| 7.6 7.3 6.9 5.9 5.0 3.9 4.0 4.4 4.7 5.2 5.9 6.3 | 5.5 ARCTIC VILLAGE AP AWOS |PARC|1996-2006| 2.8 2.8 4.2 4.9 5.8 7.0 6.9 6.7 5.2 4.0 2.7 3.3 | 4.6 ATKA AIRPORT AWOS |PAAK|2000-2006| 15.1 15.1 13.1 15.0 13.4 12.4 11.9 10.7 13.5 14.5 14.7 14.4 | 13.7 BARROW AIRPORT ASOS |PABR|1996-2006| 12.2 13.1 12.4 12.1 12.4 11.5 12.6 12.5 12.6 14.0 13.7 13.1 | 12.7 BARTER ISLAND AIRPORT |PABA|1996-2006| -

Backcountry Camping Guide

National Park Service Denali National Park and Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior Backcountry Camping Guide Michael Larson Photo Getting Started Getting a Permit Leave No Trace and Safety This brochure contains information vital to the success of your Permits are available at the Backcountry Desk located in the Allow approximately one hour for the permit process, which Camping backcountry trip in Denali National Park and Preserve. The follow- Visitor Access Center (VAC) at the Riley Creek Entrance Area. consists of five basic steps: There are no established campsites in the Denali backcountry. Use ing paragraphs will outline the Denali backcountry permit system, the following guidelines when selecting your campsite: the steps required to obtain your permit, and some important tips for a safe and memorable wilderness experience. Step 1: Plan Your Itinerary tion that you understand all backcountry rules and regula- n Your tent must be at least 1/2-mile (1.3 km) away from the park road and not visible from it. Visit www.nps.gov/dena/home/hiking to preplan several alter- tions. Violations of the conditions of the permit may result in adverse impacts to park resources and legal consequences. Denali’s Trailless Wilderness native itineraries prior to your arrival in the park. Building flex- n Camp on durable surfaces whenever possible such as Traveling and camping in this expansive terrain is special. The lack ibility in your plans is very important because certain units may gravel river bars, and avoid damaging fragile tundra. of developed trails, bridges, or campsites means that you are free be unavailable at the time you actually wish to obtain your Step 4: Delineate Your Map to determine your own route and discover Denali for yourself.