The Mccall Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Auction Catalog

2018 Auction Catalog 1 evening schedule 5:30 pm Dear Friends, Reception It is my pleasure to welcome you to the eighth annual Hard Hat & Black Silent Auction Tie Dinner and Auction. Tonight we gather at the Portland Art Museum to celebrate and support the work of Habitat for Humanity Portland/Metro 6:50 pm East. This evening would not be possible without our generous sponsors and donors. Thank you to those who graciously donated their time and Silent Auction Ends money to help plan this special event. Habitat has a proven model that works. Families and individuals purchase 7:00 pm an affordable home and help build it with the support of our staff and Super Silent Auction Ends volunteers. Habitat also performs critical home repairs to help prevent the displacement of homeowners with low incomes. Seating for Dinner We have developed a bold plan to triple the number of people Habitat serves each year. We need each of you to help us put this plan into action. 7:05 - 9:30 pm With every paddle raised this evening, your generous support will help Dinner even more Habitat homeowners build strength, stability, and self-reliance. Program Last year was amazing year where we raised over $500,000 at the auction. Pick Your Prize Raffle Wouldn’t it be great if we could meet or exceed that goal this year? I hope you will join my peers on the Habitat board and me by giving generously so Live Auction we can increase the impact Habitat has in our local community. -

When You Reach Me but You Will Get the Job Done

OceanofPDF.com 2 Table of Contents Things You Keep in a Box Things That Go Missing Things You Hide The Speed Round Things That Kick Things That Get Tangled Things That Stain Mom’s Rules for Life in New York City Things You Wish For Things That Sneak Up on You Things That Bounce Things That Burn The Winner’s Circle Things You Keep Secret Things That Smell Things You Don’t Forget The First Note Things on a Slant White Things The Second Note Things You Push Away Things You Count Messy Things Invisible Things Things You Hold On To Salty Things Things You Pretend Things That Crack Things Left Behind The Third Note Things That Make No Sense The First Proof Things You Give Away Things That Get Stuck Tied-Up Things Things That Turn Pink Things That Fall Apart 3 Christmas Vacation The Second Proof Things in an Elevator Things You Realize Things You Beg For Things That Turn Upside Down Things That Are Sweet The Last Note Difficult Things Things That Heal Things You Protect Things You Line Up The $20,000 Pyramid Magic Thread Things That Open Things That Blow Away Sal and Miranda, Miranda and Sal Parting Gifts Acknowledgments About the Author 4 To Sean, Jack, and Eli, champions of inappropriate laughter, fierce love, and extremely deep questions 5 The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. —Albert Einstein The World, As I See It (1931) 6 Things You Keep in a Box So Mom got the postcard today. It says Congratulations in big curly letters, and at the very top is the address of Studio TV-15 on West 58th Street. -

Small Mentor-Protege Program

File Name: 0802181551_080118-807313-SBA-FY2018First [START OF TRANSCRIPT] Carla: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome and thank you for joining today's live SBA web conference. Please note that all participant lines will be muted for the duration of this event. You are welcome to submit written questions during the presentation and these will be addressed during Q&A. To submit a written question, please use the chat panel on the right-hand side of your screen. Choose all panelists from the Send To drop down menu. If you require technical assistance, please send a private note to the event producer. I would now like to formally begin today's conference and introduce Chris Eischen. Chris, please go ahead. Chris: Thank you Carla. Hello everyone and welcome to SBA's First Wednesday webinar series. For today's session, we'll be focusing on the All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and by the end of the program you should have a better understanding of this topic as well as the resources available to you. If you are new to our event, this is a webinar series that focuses on getting subject matter experts on specific small business programs, in this case, All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and having them provide you with valuable information you can use in the performance of your job as an SBA employee, a member of the Federal acquisition community, or a PTAC employee. We appreciate you taking this time to join us on the August edition of SBA's First Wednesday webinar series, and we hope that you benefit from today's session. -

Tiny Spaces Put Squeeze on Parking

TACKLING THE GAME — SEE SPORTS, B8 PortlandTribune THURSDAY, MAY 8, 2014 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDONDAILYONDAAILYILY PAPERPAPER • PORTLANDTRIBUNE.COMPORTLANDTRIBUNEPORTLANDTRIBUNE.COMCOM • PUBLISHEDPUBLISHED TUESDAYTUESDAY ANDAND THTHURSDAYURRSDSDAYAY ■ Coming wave of micro apartments will increase Rose City Portland’s density, but will renters give up their cars? kicks it this summer as soccer central Venture Portland funds grants to lure crowds for MLS week By JENNIFER ANDERSON The Tribune Hilda Solis lives, breathes, drinks and eats soccer. She owns Bazi Bierbrasserie, a soccer-themed bar on Southeast Hawthorne and 32nd Avenue that celebrates and welcomes soccer fans from all over the region. As a midfi elder on the Whipsaws (the fi rst fe- male-only fan team in the Timbers’ Army net- work), Solis partnered with Lompoc Beer last year to brew the fi rst tribute beer to the Portland Thorns, called Every Rose Has its Thorn. And this summer, Solis will be one of tens of thousands of soccer fans in Portland celebrating the city’s Major League Soccer week. With a stadium that fi ts just 20,000 fans, Port- land will be host to world championship team Bayern Munich, of Germany, at the All-Star Game at Jeld-Wen Field in Portland on Aug. 6. “The goal As fans watch the game in is to get as local sports bars and visitors fl ock to Portland for revelries, many fans it won’t be just downtown busi- a taste of nesses that are benefi ting from all the activity. the MLS Venture Portland, the city’s All-Star network of neighborhood busi- game ness districts, has awarded a The Footprint Northwest Thurman Street development is bringing micro apartments to Northwest Portland — 50 units, shared kitchens, no on-site parking special round of grants to help experience. -

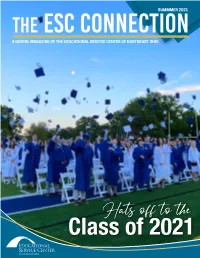

Hats Off to the Class of 2021

SUMMMER 2021 THE ESC CONNECTION A DIGITAL MAGAZINE OF THE EDUCATIONAL SERVICE CENTER OF NORTHEAST OHIO Hats off to the Class of 2021 Educational Service Center (ESC) of Northeast Ohio 1 6393 Oak Tree Blvd. Independence, OH 44131 (216) 524-3000 Fax (216) 524-3683 Superintendent’s Robert A. Mengerink Superintendent message Jennifer Dodd Director of Operations and Development By Dr. Bob Mengerink, Superintendent Steve Rogaski Director of Pupil Services Dear Colleagues, Bruce G. Basalla Treasurer As you all begin your summer, I hope you are all able to reflect on this past school year and find some positive aspects of the challenges you faced. This may be the new skills you have learned in technology or creative ways of expanding learning options for students. It could be the reminder of how GOVERNING BOARD we can and should lean on colleagues for support. Perhaps it is a greater Christine Krol President appreciation for understanding and addressing the non-academic needs of students. It might be realizing how adaptable we really are at accepting Anthony Miceli changes. Or maybe it’s remembering to slow down and prioritize what is Vice President most important for our students, ourselves and our families. Whatever it is, Carol Fortlage you should all be proud of how you have taken these challenges, led with Tony Hocevar grace and continuously identified solutions for your students, parents and Frank Mahnic, Jr. community. While there will always be challenges and controversy ahead in leading and transforming schools, my sincerest wish for you this summer is Editor: to do those things that will allow you to recharge yourself both physically and Nadine Grimm mentally while remembering that you are truly our unsung heroes. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 2

February 12, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 2 1933 the challenges of our time? Those are terrible costs of America’s revolution a profound personal commitment to the discussions the Abraham Lincoln could always be seen—in Lincoln’s human rights. We will remember not Bicentennial Commission hopes to fos- words—‘‘in the form of a husband, a fa- only his courage and his optimism, but ter as America prepares to celebrate ther, a son or a brother. A living also his deep affection for his adopted the bicentennial of the birth of its history was to be found in every family country. He leaves behind a legacy of greatest President. in the limbs mangled, [and] in the hope and inspiration. I encourage everyone to go to the scars of wounds received . ’’ On a personal level, it was an honor Commission’s Web site at Lincoln went on to say: to call TOM a colleague and a friend. I www.lincolnbicentennial.com, learn But those histories are gone. They were was proud to work with him on so more about Lincoln and about how the pillars of liberty; and now that they have many important issues. your community can plan to celebrate crumbled away, that temple must fall—un- I remember working with him to se- his birthday. President Lincoln’s less we, their descendants, supply their place cure funding to build a tunnel to by- adopted hometown of Springfield is with other pillars. pass a section of Route 1 that was so also my adopted hometown. I have I would like to think that Lincoln frequently closed by landslides that it lived there almost 40 years now. -

Finance Committee

05/08/2006 Finance 1 COMMITTEE ON FINANCE May 8, 2006 6:00 PM Vice-Chairman Gatsas called the meeting to order. Vice-Chairman Gatsas called for the Pledge of Allegiance, this function being led by Alderman Roy. A moment of silent prayer was observed. The Clerk called the roll. There were twelve Aldermen present. Present: Aldermen Roy, Gatsas, Long, Duval, Osborne, Pinard, Lopez, Shea, DeVries, Smith, Thibault and Forest Absent: Aldermen O’Neil and Garrity Messrs.: David Cornell, Tom Nichols, Stephan Hamilton, Jim Hoben, Denise Boutilier, Kevin Clougherty, Randy Sherman, Virginia Lamberton Vice-Chairman Gatsas advises that the purpose of the meeting shall be continuing discussions relating to the proposed FY2007 municipal budget and we’ll just change a little bit of the order and apologize but there are some people that had some commitments and have the Assessors go first followed by Traffic and then Finance. Board of Assessors Mr. David Cornell, Chairman of the Board of Assessors, stated today we will be presenting information on the exemption analysis giving an update of exactly where we’re at with our 2006 projected tax base. Historically the Mayor and Board of Aldermen have adjusted the exemption amounts during reval years. Our goal in this process is to provide the Mayor and the Aldermen with as much factual information so they can make an informed decision on this very important topic. Certainly we feel our role in this process is advisory in nature and some of the figures that we’ve provided to you aren’t necessarily our recommendations but they’re the figures that need to be adjusted to if the goal of the Aldermen is to keep the same proportional benefit before the reval and after the reval. -

Marco Farfan: a Rising Star from Southeast Portland Emerges for Timbers

Marco Farfan: A rising star from Southeast Portland emerges for Timbers June 10, 2017 By Jamie Goldberg While some of his Centennial High School classmates earn extra cash by working minimum wage jobs making sandwiches, flipping burgers or frothing up Grande Lattes at Starbucks, Marco Farfan plays soccer for the Portland Timbers. That's right. Marco Farfan - high school student/professional athlete. As the youngest-ever player to sign with the Timbers, Farfan has followed an unusual path. He made the leap this year from the Timbers youth academy team, signing a contract with the professional club worth $53,000 per year. But while his life has changed dramatically over the last eight months, the 18-year-old is quick to downplay his achievement. That might be because he doesn't quite grasp how unusual his experience is. "It took me about a month to get used to it, but now I'm just focused on working hard, so I can get better down the road," Farfan said. "I'm 18 right now, but that's not going to last forever. I have to have the right mindset that I can go out there every day and compete." * * * Farfan grew up in a modest home on the border of Southeast Portland and Gresham dreaming of one day becoming a professional soccer player. But neither he nor his family imagined that he would make it to the pro level before earning his college diploma - let alone before finishing high school. His father, Roberto, who spent his own childhood in Mexico surrounded by an intense soccer- crazed culture, made sure to teach all three of his children about his beloved sport. -

Portland Timbers

Portland Timbers 2001 SW 31st Avenue Hallandale, FL 33009 www.mitchellane.com John Bankston Copyright © 2019 by Mitchell Lane Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Designer: Ed Morgan Editor: Sharon F. Doorasamy Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bankston, John, 1974- author. Title: Portland Timbers / by John Bankston. Description: Hallandale, FL : Mitchell Lane Publishers, 2019. | Series: Major League Soccer | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018003131| ISBN 9781680202625 (library bound) | ISBN 9781680202632 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Portland Timbers (Soccer team)—History—Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC GV943.6.P58 B36 2018 | DDC 796.334/640979549—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003131 PHOTO CREDITS: Design Elements, freepik.com, Cover Photo: Jonathan Ferrey/Getty Images, p.3 freepik.com, p.5 freepik.com, p.7 Brian Bahr/Getty Images, p. 8 public doman, p. 11 freepik.com, pp. 12-13 Steve Dykes/Getty Images, p. 14 Steve Dykes/Getty Images, p. 15 freepik.com, p. 17 Steve Dykes/Getty Images, p. 18 freepik.com, p. 21 Rich Lam/Getty Images, p. 22 Steve Dykes/Getty Images, p. 23 Steve Dykes/Getty Images, p. 25 Steve Dykes/Getty Images, p. 26 Scott Halleran/Getty Images, Contents Chapter One “Soccer City, USA” ........................................................................ 4 Chapter Two Playing at Home: The Timbers Army ....................................... 10 Chapter Three Playing like a Champion ..............................................................16 Chapter Four The Timbers Best .........................................................................20 Chapter Five The Timbers Perfect Communicating ......................................24 What You Should Know ............................................................. -

Soccer Leagues

SOCCER LEAGUES {Appendix 5, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 14} Research completed as of July 18, 2013 MAJOR INDOOR SOCCER LEAGUE (MISL) Team: Baltimore Blast Principal Owner: Edwin F. Hale, Sr. Current Value ($/Mil): N/A Team Website Stadium: 1st Mariner Arena Date Built: 1962 Facility Cost ($/Mil): N/A Facility Financing: N/A Facility Website UPDATE: The City of Baltimore is still looking to start a private-public partnership for a new 18,500-seat arena to replace the aging 1st Mariner Arena, which will cost around $500 million. Private funding would go towards the new stadium, while public funding would be used to build a convention center. In March 2012, the state legislature declined to give $2,500,000 for design proposals until a more firm commitment to the project from the City of Baltimore is verbalized. As of February 2013, no verbal commitment had been made. Throughout 2013, the arena will be celebrating its 50th year in existence. NAMING RIGHTS: Baltimore Blast owner and 1st Mariner Bank President and CEO Ed Hale acquired the naming rights to the arena through his company, Arena Ventures, LLC, as a result of a national competitive bidding process conducted by the City of Baltimore. Arena Ventures agreed to pay the City $75,000 annually for ten years for the naming rights, which started in 2003. © Copyright 2013, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Milwaukee Wave Principal Owner: Jim Lindenberg Current Value ($/Mil): N/A Team Website Stadium: U.S. Cellular Arena Date Built: 1950 Facility Cost ($/Mil): 10 Facility Financing: N/A Facility Website Update: In June 2013, the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee announced that it will return to the U.S. -

Jeralynn Sue Tharaldson

WALLER: This interview is taking place on 09-15-83, at 10~10 a.m., and the interview is with JERALYNN SUE THARALDSON. Your date of birth Jeri? H () JERALYNN: 07-20-61. ~ '# WALLER: Where do you live now? JERALYNN: 3824 Grand Avenue. WALLER: And your telephone number? JERALYNN: 624-2280 WALLER: And this interview is being conducted by Lt. Waller concerning the death investigation of Sally Tharaldson and Virgil La Panta. Now as I said when we talked briefly before, turning the tape recorder on, you were interviewed by Sgt. Hall? JERALYNN: Yes WALLER: A short time after your Mother's disappearance? JERALYNN: Yes WALLER: And what we are going to do here is go over the in formation that you provided at that time, and also I am going to ask you some other questions. JERALYNN: Yes WALLER: And you are here on your own, correct? JERALYNN: Yes WALLER: I understand that you are the natural daughter of both Jerry and SallY? JERALYNN: Yes WALLER: Are there any other children that are? JERALYNN: The four boys, no. WALLER: Okay, they were Sally's children by a previous marriage. Is that correct? JERALYNN: Yes WALLER: And that includes Terry, Tommy, e_ ..... ~~._._._'I!. JERALYNN: Timmy. -1 WALLER: Timmy, JERALYNN: Tony. WALLER: And Tony, okay. Do you have any other sisters? JERALYNN: No. WALLER: And you were living with your parents .. JERALYNN: Yes. WALLER: At the time that your Mother disappeared? JERALYNN: Yes. WALLER: Now, can we go back to that time. Do you remember it fairly clearly? JERALYNN: Not to 5 years ago, that's a while. -

Timbers Army

GREEN AND GOLD WE’RE GONNA WIN THE LEAGUE MIGHTY PTFC Tune: “Bella Ciao” We’re gonna win the league (x2) Allez Allez Alo (x2) We are the Timbers, the Portland Timbers, I don’t know how, I don’t know when We are the Rose City Green and Gold, Green and Gold, But we’re gonna win the league! The mighty PTFC Green and Gold, Gold, Gold! (2x slow with overhead claps, 2x fast) With our friends now, up to the city, ROSE CITY, WHOA-OH We’re gonna shake the gates of hell! Rose City, Whoa-oh (x2) MENTAL AND GREEN Stand for the boys in green Tune: “You are my Sunshine” Next time you see us, we may be smiling, The best you’ve ever seen We are the Portland - The Portland Timbers Green and Gold, Green and Gold, We are mental - And we are green Green and Gold, Gold, Gold! PARTY IN PORTLAND We are the greatest - Football supporters Maybe in prison, or on the TV, We’ll sing for you Timbers That the world has ever seen. We’ll say the Timbers brought us here! ‘Til you finish the fight There’s a party in Portland BURY ME IN TIMBERS GREEN KEEP IT UP No one’s sleeping tonight And when I go (x2) Tune: Kashima Antlers chant After 2nd time, spin scarves, wave flags: la la lalala la la, etc And when I go make sure I’m wearing green and gold Whoa-oh-oh, whoa-oh-oh, Wave flags duing this part: whoa-oh-oh-oh-ohh! (2X) MENTAL AND BARMY Bury me in Timbers Green, Ohh-ohh Keep it up, Rose City! We are Timbers Army Bury me in Timbers Gold, Ahh-ahh Don’t let up, no pity! We are mental and we’re barmy Bury me in Timbers Green, Ohh-ohh Keep it up, Rose City! True supporters forever more Bury me in Timbers Gold, Ahh-ahh Whoa-oh-oh-oh-ohh! I WANNA BE ROSE CITY PORTLAND WE LOVE YOU SO SOMOS TIMBERS Tune: “Anarchy in the UK” Portland we love you so Ole Ole Ole, Ole Ole Ola I am a Timbers fan - And I am an Oregonian And where you go we will follow Sooo somos Timbers, I know what I want and I know how to get it Portland we love you so Portland Timbers, vamos a ganar I wanna destroy Seattle scum You’ve stolen our hearts.