To Go to Keith Jarrett Interview On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Sanitation in the Khuvsgul Area, Northern Mongolia: Socio-Cultural Parameters and Acceptance

Department of Geosciences, University of Basel Institute of Geography Ecological Sanitation in the Khuvsgul Area, Northern Mongolia: Socio-Cultural Parameters and Acceptance An Evaluation of the Current Sanitation Situation in the Khuvsgul Area and a Study about the Acceptance and Suitability of the Ecosan Approach in Mongolia Master’s Thesis in the College of Social Sciences Katharina Conradin November 2007 Supervisor: Prof. (em.) Dr. rer. nat. Dr. h.c. Hartmut Leser Co-Supervisor: Dr. rer. nat. Johannes Heeb © 2007: Katharina Conradin Winkelriedplatz 2 CH-4053 Basel Switzerland +41 (0)79 660 38 66 [email protected] PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Preface and Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been written had there not been a series of coincidences. Had I and my partner not chosen to go mountaineering in Mongolia, I would never have gotten to know this beautiful country. And had we not been so exhausted after six weeks of hard mountain climbing, we may not have gone to Lake Khuvsgul at all. Once there, I had recognized the need for sanitary improvements at once, but thought a project impossible just on my own. Had not a series of mishaps lead to the fact that we were among the last people to check in at the small airport in Muren, the capital town of the Khuvsgul aimag, I would never have stood behind Kent Madin, a lodge operator in Khatgal, who – also coincidentally – happened to walk around with a urine-separating toilet under his arms… It was this coincidental meeting which started this thesis. I owe Kent and his Mongolian partner Chinbat my deepest gratitude. -

Dante Anzolini

Music at MIT Oral History Project Dante Anzolini Interviewed by Forrest Larson March 28, 2005 Interview no. 1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library Transcribed by: Mediascribe, Clifton Park, NY. From the audio recording. Transcript Proof Reader: Lois Beattie, Jennifer Peterson Transcript Editor: Forrest Larson ©2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library, Cambridge, MA ii Table of Contents 1. Family background (00:25—CD1 00:25) ......................................................................1 Berisso, Argentina—on languages and dialects—paternal grandfather’s passion for music— early aptitude for piano—music and soccer—on learning Italian and Chilean music 2. Early musical experiences and training (19:26—CD1 19:26) ............................................. 7 Argentina’s National Radio—self-guided study in contemporary music—decision to become a conductor—piano lessons in Berisso—Gilardo Gilardi Conservatory of Music in La Plata, Argentina—Martha Argerich—María Rosa Oubiña “Cucucha” Castro—Nikita Magaloff— Carmen Scalcione—Gerardo Gandini 3. Interest in contemporary music (38:42—CD2 00:00) .................................................14 Enrique Girardi—Pierre Boulez—Anton Webern—Charles Ives—Carl Ruggles’ Men and Mountains—Joseph Machlis—piano training at Gilardo Gilardi Conservatory of Music—private conductor training with Mariano Drago Sijanec—Hermann Scherchen—Carlos Kleiber— importance of gesture in conducting—São Paolo municipal library 4. Undergraduate education (1:05:34–CD2 26:55) -

IN CONCERT: Formidable Jazz Foursome

Welcome, ANGIE | Logout SANTA BARBARA Wednesday, February 19, 2014 62°Full forecast Home Local Nation/World Editorials Opinions-Letters Obituaries Real Estate Classifieds Special Publications Archives Scene Share Tweet 0 Home » Scene IN CONCERT: Formidable Jazz Foursome - KICKING OFF THE NEW 'JAZZ AT THE LOBERO' SERIES, THE SPRING QUARTET BRINGS TO TOWN AN ALL- STAR GROUP WITH JOE LOVANO, JACK DEJOHNETTE, ESPERANZA SPALDING, AND LEO GENOVESE By Josef Woodard, News-Press Correspondent February 14, 2014 8:04 AM IN CONCERT Related Stories The Spring Quartet ACT 1, SCENE 2, CLO's show business Dec 14, 2000 When: 8 p.m. Tuesday IN CONCERT: The House of Swing in the House - Jazz at Lincoln Center, led by trumpeter-jazz Where: Lobero Theater, 33 E. Canon Perdido St. spokesman Wynton Marsalis, returns to Santa Barbara on Sunday at The Granada Cost: $40-$105 Mar 8, 2013 Information: 963-0761, lobero.com Balancing home budget the Gray Davis way May 29, 2003 As a fitting, grand-opener concert in the new "Jazz at the Lobero" IN CONCERT : A different Nashville skyline - series in the newly renovated, and distinctly jazz-friendly theater Veteran musician David Olney headlines Saturday's (a condition duly noted by Down Beat magazine), a special, all-star Sings like Hell show at Lobero Theatre group gives its musical blessing Tuesday night. Enter the stellar Aug 22, 2008 aggregation calling itself the Spring Quartet, and featuring some of the most rightfully and highly respected musicians on their IN CONCERT: Soul on the Rough Side - A 'garage respective instruments — tenor saxophone mater Joe Lovano, soul' band out of Austin, Texas, Black Joe Lewis & the drummer Jack DeJohnette, Grammy-kissed young bassist-singer Honeybears is spearheaded by the high energy, James dynamo Esperanza Spalding and, from the player deserving wider Brown-inspired Lewis recognition corner, pianist Leo Genovese. -

John Stephens, Composer 2000 Johansen International Competition for Young String Players

John Stephens, Composer 2000 Johansen International Competition for Young String Players John Stephens was born in Washington, DC, and Dr. Stephens’s music is published in the United beginning at age 8 studied piano, followed by trumpet, States by MMB and by TAP Music and in France by cello, and harmony. During the 1960s, he held a Vandoran. He has served on the faculties of Catholic trumpet chair regularly with the summer National University; George Washington University; American Symphony Orchestra (NSO), known as the Watergate University; and, with the American Camerata, as Artist Symphony. in Residence at the University of the District of Columbia. His Creations for Trombone & String Quartet His career as a composer has brought him and Three for Four Plus One were released on AmCam numerous awards and scholarships. He received a Recordings. Doctor of Musical Arts degree from Catholic University and was elected to Pi Kappa Lambda, the Dr. Stephens’s conducting experience led him to the honorary society for music graduates. Other awards Academy of Music in Basel, Switzerland, where he included four scholarships to the Bennington studied with Pierre Boulez. He was Music Director for Composers’ Conference at Bennington, VT, where he Clar-Fest International in the 1980s and early 1990s. He appeared as composer and orchestral player with the served as music director of the John Cage Festival conference’s resident orchestra. His first work for string Orchestra and as conductor of the Sistrum New Music orchestra was awarded a National Young Composers’ Ensemble. He served as tour conductor with the Lydian Award, as was his first choral piece. -

When You Reach Me but You Will Get the Job Done

OceanofPDF.com 2 Table of Contents Things You Keep in a Box Things That Go Missing Things You Hide The Speed Round Things That Kick Things That Get Tangled Things That Stain Mom’s Rules for Life in New York City Things You Wish For Things That Sneak Up on You Things That Bounce Things That Burn The Winner’s Circle Things You Keep Secret Things That Smell Things You Don’t Forget The First Note Things on a Slant White Things The Second Note Things You Push Away Things You Count Messy Things Invisible Things Things You Hold On To Salty Things Things You Pretend Things That Crack Things Left Behind The Third Note Things That Make No Sense The First Proof Things You Give Away Things That Get Stuck Tied-Up Things Things That Turn Pink Things That Fall Apart 3 Christmas Vacation The Second Proof Things in an Elevator Things You Realize Things You Beg For Things That Turn Upside Down Things That Are Sweet The Last Note Difficult Things Things That Heal Things You Protect Things You Line Up The $20,000 Pyramid Magic Thread Things That Open Things That Blow Away Sal and Miranda, Miranda and Sal Parting Gifts Acknowledgments About the Author 4 To Sean, Jack, and Eli, champions of inappropriate laughter, fierce love, and extremely deep questions 5 The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. —Albert Einstein The World, As I See It (1931) 6 Things You Keep in a Box So Mom got the postcard today. It says Congratulations in big curly letters, and at the very top is the address of Studio TV-15 on West 58th Street. -

Small Mentor-Protege Program

File Name: 0802181551_080118-807313-SBA-FY2018First [START OF TRANSCRIPT] Carla: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome and thank you for joining today's live SBA web conference. Please note that all participant lines will be muted for the duration of this event. You are welcome to submit written questions during the presentation and these will be addressed during Q&A. To submit a written question, please use the chat panel on the right-hand side of your screen. Choose all panelists from the Send To drop down menu. If you require technical assistance, please send a private note to the event producer. I would now like to formally begin today's conference and introduce Chris Eischen. Chris, please go ahead. Chris: Thank you Carla. Hello everyone and welcome to SBA's First Wednesday webinar series. For today's session, we'll be focusing on the All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and by the end of the program you should have a better understanding of this topic as well as the resources available to you. If you are new to our event, this is a webinar series that focuses on getting subject matter experts on specific small business programs, in this case, All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and having them provide you with valuable information you can use in the performance of your job as an SBA employee, a member of the Federal acquisition community, or a PTAC employee. We appreciate you taking this time to join us on the August edition of SBA's First Wednesday webinar series, and we hope that you benefit from today's session. -

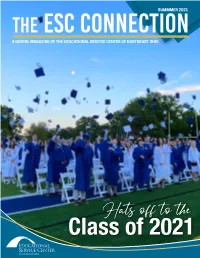

Hats Off to the Class of 2021

SUMMMER 2021 THE ESC CONNECTION A DIGITAL MAGAZINE OF THE EDUCATIONAL SERVICE CENTER OF NORTHEAST OHIO Hats off to the Class of 2021 Educational Service Center (ESC) of Northeast Ohio 1 6393 Oak Tree Blvd. Independence, OH 44131 (216) 524-3000 Fax (216) 524-3683 Superintendent’s Robert A. Mengerink Superintendent message Jennifer Dodd Director of Operations and Development By Dr. Bob Mengerink, Superintendent Steve Rogaski Director of Pupil Services Dear Colleagues, Bruce G. Basalla Treasurer As you all begin your summer, I hope you are all able to reflect on this past school year and find some positive aspects of the challenges you faced. This may be the new skills you have learned in technology or creative ways of expanding learning options for students. It could be the reminder of how GOVERNING BOARD we can and should lean on colleagues for support. Perhaps it is a greater Christine Krol President appreciation for understanding and addressing the non-academic needs of students. It might be realizing how adaptable we really are at accepting Anthony Miceli changes. Or maybe it’s remembering to slow down and prioritize what is Vice President most important for our students, ourselves and our families. Whatever it is, Carol Fortlage you should all be proud of how you have taken these challenges, led with Tony Hocevar grace and continuously identified solutions for your students, parents and Frank Mahnic, Jr. community. While there will always be challenges and controversy ahead in leading and transforming schools, my sincerest wish for you this summer is Editor: to do those things that will allow you to recharge yourself both physically and Nadine Grimm mentally while remembering that you are truly our unsung heroes. -

Jazz Trio Plays Spanos Theatre Oct. 4

Cal Poly Arts Season Launches with Jazz Trio Oct. 4 http://www.calpolynews.calpoly.edu/news_releases/2006/September... Skip to Content Search Cal Poly News News California Polytechnic State University Sept. 11, 2006 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Jazz Trio Plays Spanos Theatre Oct. 4 SAN LUIS OBISPO – In a spectacular showcase featuring jazz greats Bill Frisell (guitar/banjo), Jack DeJohnette (drums, percussion, piano) and Jerome Harris (electric bass/vocals), Cal Poly Arts launches its new 2006-07 performing arts season. The trio of master musicians will perform on Wednesday, October 4, 2006 at 8 p.m. in the Spanos Theatre. The evening will include highlights from the acclaimed release, “The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers.” Recorded at Seattle’s Earshot Festival in October 2001, “The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers” brilliantly captures the collaboration of two unparalleled musical visionaries: Jack DeJohnette -- “our era’s most expansive percussive talent” (Jazz Times) -- and Bill Frisell, “the most important jazz guitarist of the last quarter of the 20th century” (Acoustic Guitar). DeJohnette and Frisell first worked together in 1999. “We immediately had a rapport and we talked about doing more,” DeJohnette recalls. Frisell needed no convincing: “I have been such a fan of Jack’s since the late ’60s when I first heard him,” the guitarist says. “He’s been such an influence and inspiration throughout my musical life.” The two got together the afternoon before the 2001 Earshot concert and at the soundcheck, ran through a couple of numbers, but the encounter was largely improvised. “We had a few themes prepared,” Frisell says, “but it was pretty much just start playing, and go for it.” According to DeJohnette, “Bill and I co-composed in real time, on the spot” for “The Elephant Sleeps...” The album features 11 tracks covering a breadth of sonic territories. -

Press Release | Berlin, May 4, 2021

If you have trouble reading this email, click here for the web version. Press Release | Berlin, May 4, 2021 “Love Longing Loss”: At Home with Charles Lloyd During Isolation New Film Commissioned by the Pierre Boulez Saal to Premiere on May 11 The Pierre Boulez Saal is premiering exclusively on its website a film documenting a year in the life of jazz musician Charles Lloyd during the Covid-19 pandemic. Commissioned by the Pierre Boulez Saal after the corona-related cancellation of two concerts in the hall, Lloyd’s wife, painter and video artist Dorothy Darr, set about creating a film portrait of the artist, documenting the time spent in isolation at the couple’s home in Santa Barbara, California. Shot over the course of several months using iPhone and Lumix cameras as well as a portable Zoom recorder, the film presents a world of Lloyd’s musical compositions, intertwined with his reflections on solitude, resistance, and ancestry. The film project is part of the immediate-action program for corona-related investments in cultural venues, NEUSTART KULTUR, by the German Federal Government. The film will be made available to music lovers around the world for free streaming from May 11 to June 11. In “Love Longing Loss,” Charles Lloyd shares early memories of listening to and playing music, as well as stories about the struggle of his ancestors in fighting for liberty and freedom. These insights are interwoven with musical passages, including new compositions and classics, in which Lloyd performs on saxophone, piano, flute, and tárogató. With Lloyd describing his personal journey as “swimming away with my stories and ancestors,” the film is an invitation to connect and make peace with our own experiences and troubles. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 2

February 12, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 2 1933 the challenges of our time? Those are terrible costs of America’s revolution a profound personal commitment to the discussions the Abraham Lincoln could always be seen—in Lincoln’s human rights. We will remember not Bicentennial Commission hopes to fos- words—‘‘in the form of a husband, a fa- only his courage and his optimism, but ter as America prepares to celebrate ther, a son or a brother. A living also his deep affection for his adopted the bicentennial of the birth of its history was to be found in every family country. He leaves behind a legacy of greatest President. in the limbs mangled, [and] in the hope and inspiration. I encourage everyone to go to the scars of wounds received . ’’ On a personal level, it was an honor Commission’s Web site at Lincoln went on to say: to call TOM a colleague and a friend. I www.lincolnbicentennial.com, learn But those histories are gone. They were was proud to work with him on so more about Lincoln and about how the pillars of liberty; and now that they have many important issues. your community can plan to celebrate crumbled away, that temple must fall—un- I remember working with him to se- his birthday. President Lincoln’s less we, their descendants, supply their place cure funding to build a tunnel to by- adopted hometown of Springfield is with other pillars. pass a section of Route 1 that was so also my adopted hometown. I have I would like to think that Lincoln frequently closed by landslides that it lived there almost 40 years now. -

Paul Bley Footloose Mp3, Flac, Wma

Paul Bley Footloose mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Footloose Country: France Released: 1969 Style: Free Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1851 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1832 mb WMA version RAR size: 1749 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 434 Other Formats: MP4 AHX MOD FLAC MMF MP1 WAV Tracklist Hide Credits When Will The Blues Leave A1 Written-By – Ornette Coleman A2 Floater A3 Turns A4 Around Again B1 Syndrome B2 Cousins B3 King Korn B4 Vashkar Companies, etc. Licensed From – Savoy Records Printed By – I.D.N. Recorded At – Medallion Studio Credits Bass – Steve Swallow Design – Pierre Bompar Drums – Pete LaRoca* Liner Notes – Philippe Carles Photography By – Giuseppe Pino Piano – Paul Bley Producer [Serie Dirigee Par] – Jean-Louis Ginibre Written-By – Carla Bley (tracks: A2, A4, B1, B3, B4), Paul Bley (tracks: A3, B2) Notes Tracks A1, A2 and A4 recorded at Medallion Studios, Newark, NJ, August 17, 1962. Tracks A3, B1 to B4 recorded at Medallion Studios, Newark, NJ, September 12, 1963. Made in France Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A runout, hand-etched): BYG 529 114 A. Matrix / Runout (Side B runout, hand-etched): BYG 529 114 B Rights Society: BIEM Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year MG-12182 Paul Bley Footloose (LP, Album) Savoy Records MG-12182 US 1963 Footloose (CD, Album, CY-78987 Paul Bley Savoy Jazz CY-78987 Japan 1995 RE, RM, Pap) Footloose (CD, Album, COCB-50603 Paul Bley Savoy Jazz COCB-50603 Japan 2001 RE, RM, Pap) Footloose (LP, Album, COJY-9050 Paul Bley Savoy -

Finance Committee

05/08/2006 Finance 1 COMMITTEE ON FINANCE May 8, 2006 6:00 PM Vice-Chairman Gatsas called the meeting to order. Vice-Chairman Gatsas called for the Pledge of Allegiance, this function being led by Alderman Roy. A moment of silent prayer was observed. The Clerk called the roll. There were twelve Aldermen present. Present: Aldermen Roy, Gatsas, Long, Duval, Osborne, Pinard, Lopez, Shea, DeVries, Smith, Thibault and Forest Absent: Aldermen O’Neil and Garrity Messrs.: David Cornell, Tom Nichols, Stephan Hamilton, Jim Hoben, Denise Boutilier, Kevin Clougherty, Randy Sherman, Virginia Lamberton Vice-Chairman Gatsas advises that the purpose of the meeting shall be continuing discussions relating to the proposed FY2007 municipal budget and we’ll just change a little bit of the order and apologize but there are some people that had some commitments and have the Assessors go first followed by Traffic and then Finance. Board of Assessors Mr. David Cornell, Chairman of the Board of Assessors, stated today we will be presenting information on the exemption analysis giving an update of exactly where we’re at with our 2006 projected tax base. Historically the Mayor and Board of Aldermen have adjusted the exemption amounts during reval years. Our goal in this process is to provide the Mayor and the Aldermen with as much factual information so they can make an informed decision on this very important topic. Certainly we feel our role in this process is advisory in nature and some of the figures that we’ve provided to you aren’t necessarily our recommendations but they’re the figures that need to be adjusted to if the goal of the Aldermen is to keep the same proportional benefit before the reval and after the reval.